San Francisco – For his latest solo show, Justin Yoon set out to paint a movie.

“I didn’t want it to be literal, but meta,” the Brooklyn-based painter said of the resulting presentation of the ten thematically interconnected canvases that make up Midnight Movie, on view at Jonathan Carver Moore through October 28.

On the surface, the overarching narrative is as charming as Yoon’s diffuse pastel colour pallet: three friends and their dog attend the premier of a canonical Korean queer film. But the story quickly takes a surrealist and metafictional plunge. First off, no such film exists in real life – which was one of Yoon’s main inspirations.

Growing up in Los Angeles, Yoon has been a movie buff from a young age. He can toss off titles, quotes, and trivia as if they were written on the back of his hand and watches most movies he likes at least twice. But what’s stuck with him is what he hasn’t seen on the silver screen.

“There was never a macho, gay, male Asian character,” he said. “It was always the sissy stereotype, which is fine, but it isn’t totally representative. There’s a history being forgotten completely in the Korean community.”

Midnight Movie is an exploration of this absence. Riffing on 1970s B-movies and archetypical queer imagery, Yoon inserts queer Korean American characters into these scenes, blending a revisionist vision with nostalgia for what is already an idealized period in queer culture.

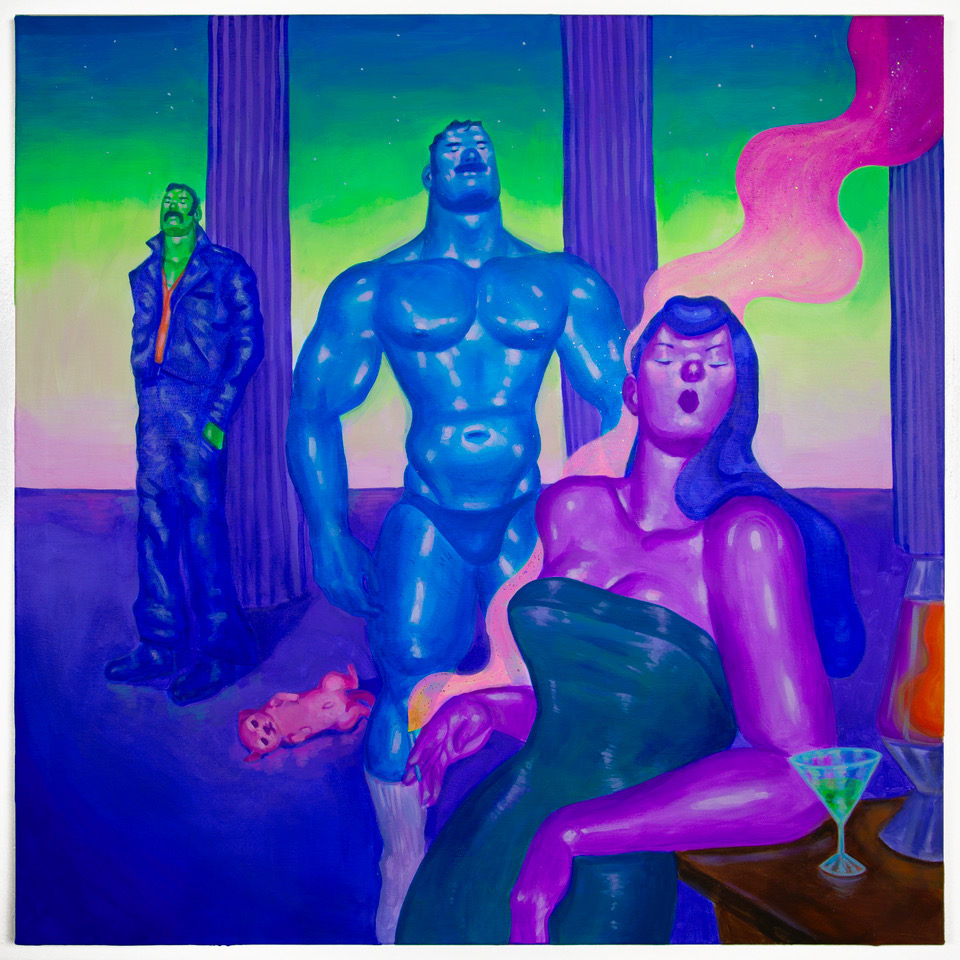

The Cast (2023) introduces us to the film’s players, a mix of characters who recur throughout Yoon’s work, as well as new additions to his ongoing roster. There’s Blue Dream and Machoman Park (blue and green-skinned muscle daddies hinting at influences from Tom of Finland to Freddie Mercury to Marlon Brando) and the magenta Marge the Space Queen, inspired by a range of glamorous femmes from Betty Page and Marilyn Monroe to K-pop stars as well as Yoon’s own mother and friends who embody these characteristics. And, of course, there’s Fivepoundz, the pink Bichon Frisé.

Yoon hopes that leaning into archetypical representations of queerness for his characters’ designs, as well as relying on signifiers like colour coding, makes them more accessible to a broad range of viewers. This reliance on signifiers underscores the enacting of identity itself as social performance, which gets at the more complex and headier undertone of Midnight Movie.

The story itself is carried out over three acts, each with their own large title canvas and smaller vignettes in between.

In Act 1 (of Midnight Movie) (2023), three Blue Dreams flex their biceps on stage for the attendant audience. But this raises the first alarms of a surrealist twist: Isn’t Blue Dream meant to be in the audience? Why are there three of him? Isn’t this a movie, not a play? These questions are foundational to approaching the exhibition, which demands dynamic engagement from its viewers.

“I wanted the viewers to be both the actor and the audience,” Yoon said. “For that to be possible, the characters also had to be both the actors and the audience.”

By Act 3 (of Midnight Movie) (2023), the viewer has fully assumed this position, looking out at the cast, who is seated in a theatre watching the viewer watch them.

The utopian vision of cinematic history Yoon presents in Midnight Movie also reflects everything he adores about cinema, like a love letter to the movies he has seen himself reflected in as much as a fantasy of what could have been.

The narrative contained within Yoon’s “queer buddy movie,” as he calls it, is markedly anticlimactic. This is the romance of a lazy summer afternoon spent with friends, the euphoria of everything being okay, and a recognition of the moments that seem to be fillers as being the events that actually equal a life. At its heart, it’s a story about intimacy, though decidedly nonsexual intimacy, which is another departure from traditional representations of queer relationships.

“A lot of people experience platonic intimacy,” Yoon said, “but nobody expresses it.”

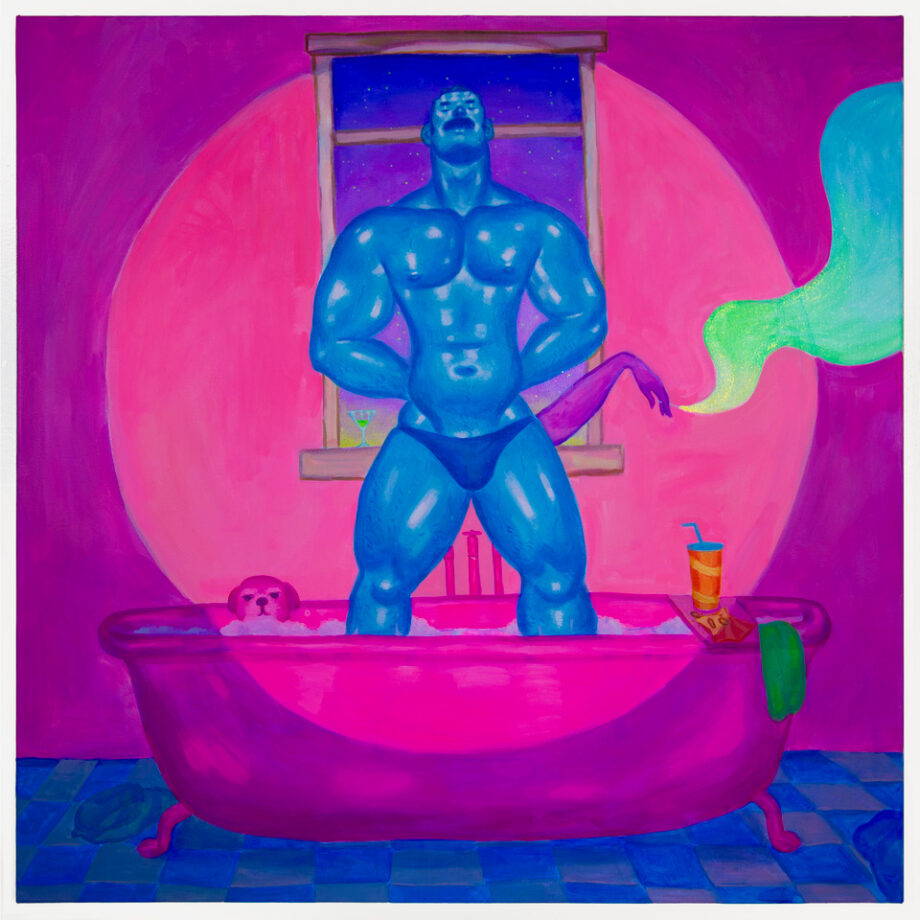

Midnight Movie is full of intimate moments shared between characters as well as between the characters and the audience. Cast Party (or the end of Midnight Movie) (2023) is a reprise of the opening canvas, in which the four main characters crowd together around a table of toxic-green martinis, puckering as if for a group selfie. In An Afternoon Martini and Gather the Wind (both 2023), Blue Dream reclines in bed and in an armchair (in the middle of a dreamy desert landscape). While his muscular blue body bursts cartoonish out of his jockstrap, these aren’t pornographic scenes – rather, they’re glimpses into the character’s private life, banal moments of rest that instil a sense of familiarity in the viewer.

Throughout Midnight Movie, Yoon deftly resists expected definitions of genre and medium alike in the interest of exploring broader themes about the value of creating art and telling stories, be it film, theatre, or graphic novels – strains of which all find their way into his paintings.

“I love the conversation between the art forms because eventually, it just becomes about creating a story,” Yoon said. “And that’s one of the most beautiful things that people can do.”

That’s the same joy that looking at Yoon’s paintings elicits. There is a sense of play (both in terms of theatricality and fun) that laces the experience.

The gentleness and lack of drama that abounds in Yoon’s paintings is noticeably un-Hollywood. The only real moment of tension in the paintings comes in a note of foreshadowing in Act 3, which shows the cast sitting in the front row of the theatre, staring up at the screen. A lone figure sits in the upper left corner, wearing a headscarf and sunglasses Audrey Hepburn-style.

“I like movies without conflicts,” Yoon said. His favourites include Before Sunset, Dazed and Confused, and Spanish Apartment. “They’re almost non-movies,” he said.

Without conflict to drive the plots of films like these – or of Yoon’s paintings – they become slice-of-life snapshots that, no matter how surreal they may be, are closer to life than many popular narratives, privileging the mundane romance of daily life and friendship. This approach feels particularly powerful when considering his intent of addressing the historical absence of queer Asian individuals in Hollywood films: there’s a matter-of-factness in the subtlety of his canvases that lends them a certain credence.

Words by Max Blue