This year has done something strange to our sense of where we are. Our confinement has been collective, and our protests globally shared. The world has felt so small. It has also, precisely because we can’t travel anywhere, never felt bigger. Before lockdown, it was quicker—and cheaper—for Londoners like me to fly to another European capital than to travel 130 miles west by train, but daily walks since March have rarely taken me more than six miles from my desk. The local has become a universe. And any artwork that has captured that reality has resonated like few before it. As the Art Institute of Chicago’s Lindsay Bosch once wrote of British video artist John Smith, “As a viewer, I am drawn to his use of his immediate surroundings to point fully outward.”

British painter Doreen Fletcher—whose solo show opened virtually at Town House Gallery, in Spitalfields, London this month—is an archivist of the similarly immediate. Since the late 1970s, she has spent an average of 28 hours a week (she keeps a detailed log in her diary) painting within a seven-mile radius, roughly, of places she’s actually lived in. And since the early 1980s, that has mostly been London. When I visited her studio in Plaistow this year, that specific area of East London had only recently made an appearance in her work. “I’ve lived here 13 years now,” she said. “Just about long enough to start painting it.”

“Daily walks since March have rarely taken me more than six miles from my desk. The local has become a universe”

Fletcher was born in Staffordshire, the daughter of a munitions factory worker turned domestic servant and a farm hand turned builder. She’s always been a worker too: “I like doing”, as she puts it. It is an outlook that sets the tone for the subjects she chooses. From the outset her work has centred on the built environment, mostly commercial, and its impermanence. “In the Potteries,” she said last year, on the occasion of a retrospective at the Nunnery Gallery in Bow, East London, “the town planners’ ethos was ‘if it’s old, let’s sweep it away’, regardless of its cultural and historical significance.” When she moved to Poplar in 1983, she saw something similar underway.

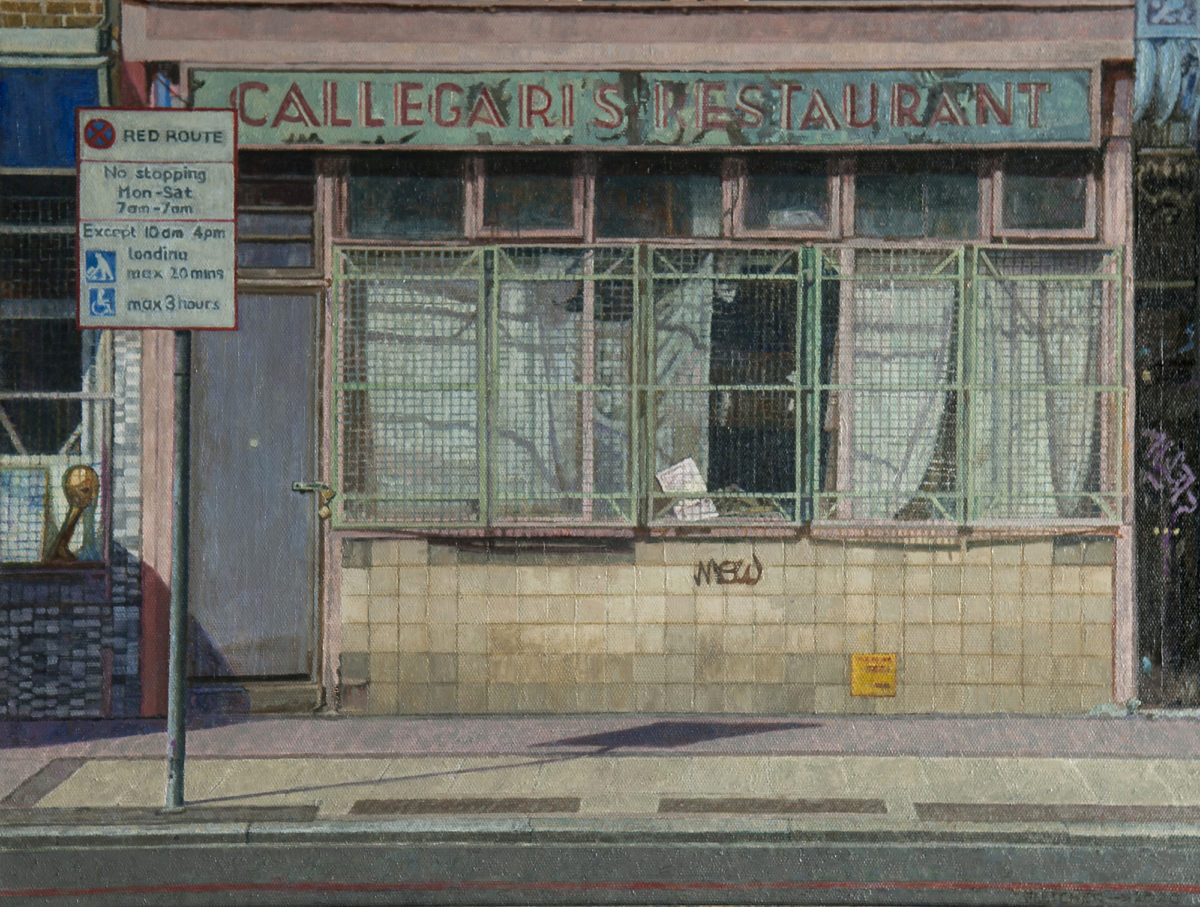

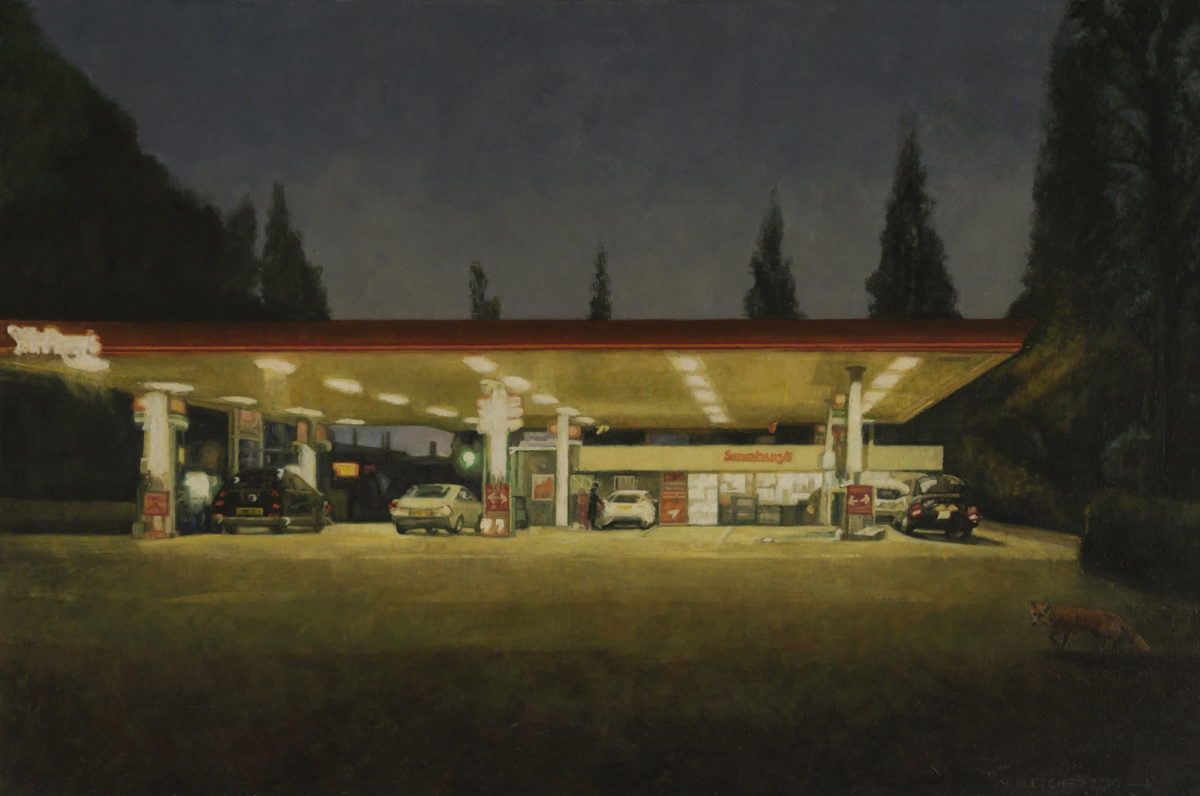

Her first paintings in the East End were of a bus stop and a cafe. She continued with street scenes—few people, the odd fox, mostly buildings—recording shop fronts, wharf entrances, graffitied railway arches, parkside popcorn stands, canalside gas holders, the pub on the corner, the shuttered laundrette. Tight realism and a lack of whimsy immediately asserted a lineage stretching back to the East London Group of the 1920s and founder John Cooper’s insistence that his evening students (who were variously deck hands, contractors and clarks by day) paint not floral arrangements but the stuff around them. There is this sense, in these early twentieth century works, as in Fletcher’s own, of an artist watching a city on the move.

Roaming the streets has always been Fletcher’s primary method for figuring out what to paint. In the 1980s, she worked as a life model. To offset the job’s sedentary nature, she would walk the 45 minutes to Aldgate from Poplar, and get the train there. Her paintings from that era are full of chipped paving slabs, rusting bins and scuffed plaster—details you only know from looking at them up close.

- Left to right: Tamara Stoll, Going Places, Ridley Road, 2011; Afro-Caribbean Foods and Grocery, Ridley Road, 2013; Market Barrow, Ridley Road, 2011. Courtesy the artist

Tamara Stoll is a German photographer who has lived in London for the better part of two decades. She has spent a good chunk of that documenting Ridley Road Market, slightly to the north of Fletcher’s turf, in Dalston. Like Brixton Market down south, it has long been a locus for diasporic diversity, political tension and real-estate threats. During lockdown, Stoll started walking from the eerily emptied market to Parliament Square. She was following the route that a group of young activists took in 1962 to protest rising fascism in the area. Even though the streets were lonesome, that journey in architectural terms alone—construction sites jostling with boarded-up immigrant businesses—tells a story of exclusion and urban power structures.

Like Fletcher, Stoll’s streetscapes are essentially—conceptually—portraits. Stoll speaks of the street as a social unit, with its surfaces bearing witness to all the exchanges it has hosted. Similarly, Fletcher says she looks for scars: “buildings that are damaged, but still surviving in some form or another.” And immediately, she adds: “But when I say buildings, I am talking about lives. Without people there are no buildings, and buildings have no function unless they are used by people.”

“When I say buildings, I am talking about lives. Without people there are no buildings”

The flaking paint and rusting metal Fletcher so meticulously records refer to actions and transactions, meet-ups and breakdowns. You can imagine a narrator telling you those stories, in the way that John Smith does in his 1993 video work, Home Suite. The camera lingers on a filthy carpeted staircase as the voiceover relays the humiliating breakup that happened right there. “I’ve got this sort of, um, I’ve got a really strong memory,” he says, “a really strong memory about these stairs.”

Young British filmmaker Beatrix Blaise talks about “contained minds”. The day I call her, she’s at home in a new part of town with nice big windows and none of the emotional baggage that came with her former place in South London, where everything was a memory. “I’m looking out my window right now,” she said. “I’m looking at a woman on her balcony in her dressing gown. And I think she’s just spotted me as well. And that’s kind of beautiful.”

Of course, a changing neighbourhood is more than the sum of its shifting parts. Fletcher, Stoll, Blaise and Smith are all looking, in their own ways, at gentrification, and the wholesale changes wrought not only on individuals but on communities. Blaise’s recent short, Tin Luck, was filmed in a single shot in Maiden Lane, a council estate north of Kings Cross. The camera pans from balcony to window, gliding up a stairwell and on to a roof, taking in this short moment in a complex community’s day—a collaboration with actors and the people who live there. The result is a beautiful airborne feather of a story, drifting in and out of individual lives.

What makes Maiden Lane so representative of London, for Blaise, is the multicultural, multiethnic community it houses. It is precisely the kind of long-term community that gentrification invariably fissures or destroys. A direct formal antecedent for Blaise’s film is Mark Lewis’s Children’s Games, shot in 2002 on the Heygate Estate in Elephant and Castle. It is an equally smooth glide up and over the walkways of a sprawling social housing complex. Only, this estate was maligned (the Art Council Collection’s write-up of the work labelled it “notoriously dangerous”) and eventually pulled down in 2011. Observers suspected at the time already that the social ills its detractors highlighted were more excuses than reality. Developers mainly wanted the land. The council mainly wanted the money. And the people who lived there? Where do they live now?

To my mind, Fletcher’s slow, oil-based notetaking on the changes occurring in her bit of East London relates directly to what has been coming out of the London music scene in the last decade or so, both in lyrics (think Little Simz reflecting on her childhood “in the flats” in 101FM) and on film. Director Yoni Lappin has made a name for himself, shooting rappers spitting bars in council estates and residential streets, the skyline a mix of new highrise, old brick and leafy trees.

He feels lucky to have come of age, professionally, just as Afrobeat and drill came to the fore in the capital: “No one would watch them if the music weren’t relevant.” Documenting the city might not be the purpose of these works, but they do a good job of it. For Londoners, trying to figure out which street Lappin’s clip for Mura Masa’s Move Me was shot on is its own kind of thrill. And like Nez Khammal’s magnificent video for Stormzy’s Blinded by Your Grace, Pt. 2, it is a record of the warmth of real London life, full of humanity and affection.

Fletcher’s medium sees her withdraw from the world for long periods of time. She talks of a certain coldness that painting demands: it’s logistical; painting just takes time. So being in lockdown, for her, is pretty much business as usual. That idea of erasure or invisibility, though, echoes across the social spectrum. It is, after all, what happens when transient, gentrifying populations come into a local neighbourhood and don’t see what—or who—was there all along.

“Erasure is what happens when gentrifying populations come into a local neighbourhood and don’t see what—or who—was there all along”

That erasure was on display in photographer Dennis Morris’s A Home from Home series about the Sikh community in Southall, Ealing, in the 1970s. These were the interiors and daily lives of an immigrant population that this country did not value. To wit, the boy and his two sisters, waiting to be bussed out to a school in a different part of town, so as not to exceed the “immigrant child quota” set by the local authority for its schools.

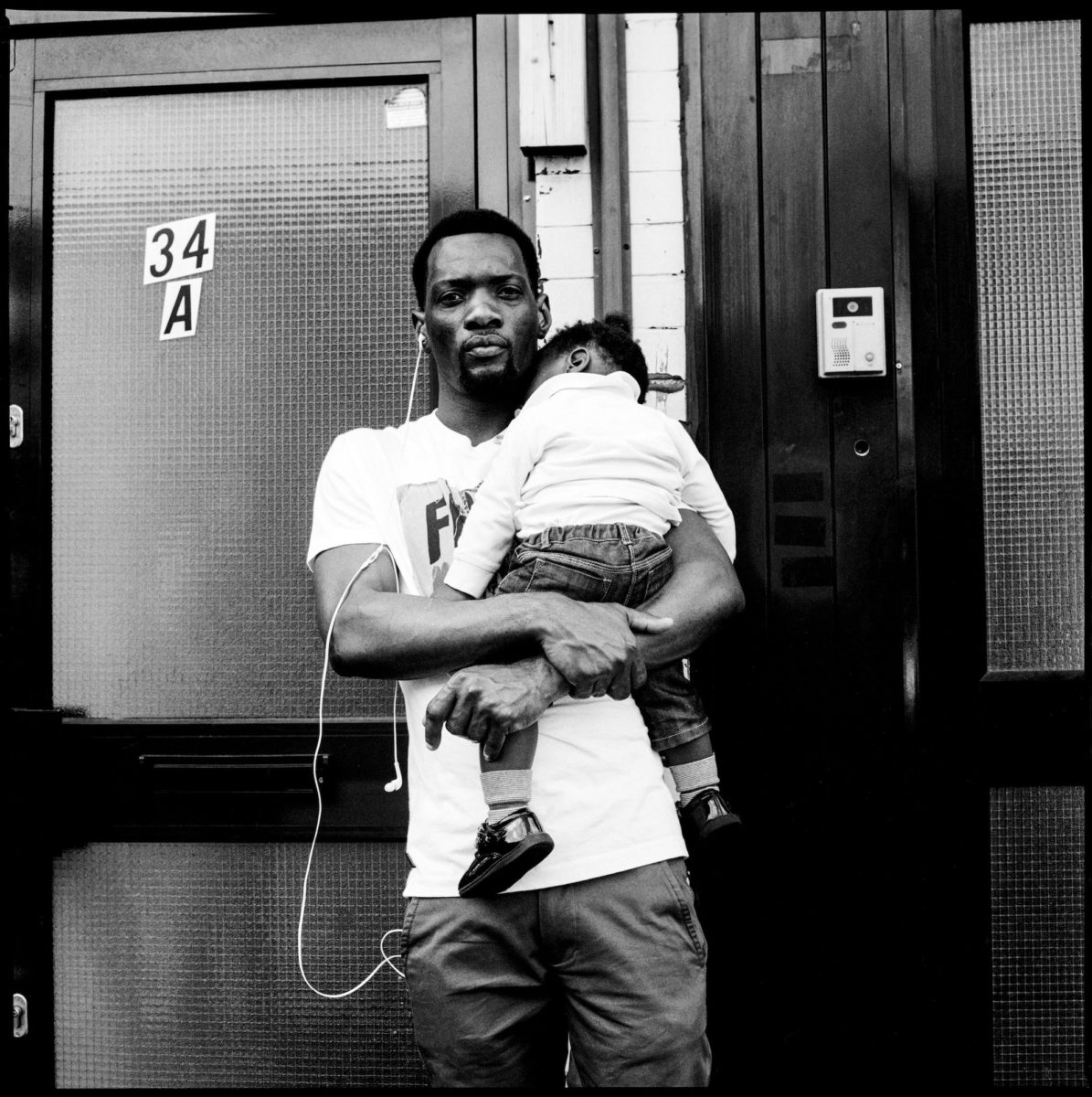

It was there at the genesis of Morris’s Growing Up Black project in Hackney. “My generation went from being ‘coloured people’ like my parents’ generation to being called black people. It took a helluva lot of faith,” he told me, “to be able to really stand up and still walk out on to the street and still say that you’re a part of England.” And that erasure is there still now, in every aspect of the Grenfell Tower disaster—a highrise hiding in plain sight in an area blinded by affluence and systemic racism; a whole community and 72 lives destroyed by institutional neglect.

- Courtesy Adama Jalloh

Much has been made of 2020 as a complete reset. While the economic upheaval has already frozen construction sites and emptied office blocks, no one yet knows the extent of the impact on the urban landscape. But the people are still here. We are all still here in our respective cities and localities. We are each part of a community. And there’s a comforting resilience to that fact. As Little Simz puts it in the last bars of 101FM, “We’re live at ya, Top of the flats, Can’t see us but you can hear us.”

Before lockdown, up and coming South London photographer Adama Jalloh spent a lot of her time reacting to the sounds of the high street: “butchers yelling prices, people haggling, school kids, worshippers yelling psalms, local characters …”. After things eased up though, she went to the park without her camera, and couldn’t stop staring. The way people communicated, what they did with their hands when laughing or excited. It was emotional, she says. “Everything felt so hyper visible; I was in awe of what I was seeing.” If artists like Jalloh, Simz and Fletcher do anything, it is exactly this: they make the unseen in the city visible.