Whether in fine art, web design, graphics, music, commercial television identity design, or the amorphous concept of interdisciplinary collaboration; the impact of Nam June Paik is everywhere. This is made vibrantly, flickeringly clear in the new major retrospective of the Korean-born artist’s work at Tate Modern.

Much of his work is underpinned by serious messages around relationships between the east and west, informed by his life spent living variously in Japan, the United States and Germany, or draws on the influences of Buddhist philosophies. But what becomes most apparent across the 200 or so photographs, films, objects and installations is a relentless drive for playfulness and experimentation with form and message. Everything could be art, everything could be subverted.

What’s also eerily clear is Paik’s apparent abilities as a seer, predicting such world-changers as the internet and the infiltration of self-as-content. Here’s five major ways Paik changed visual culture as we know it.

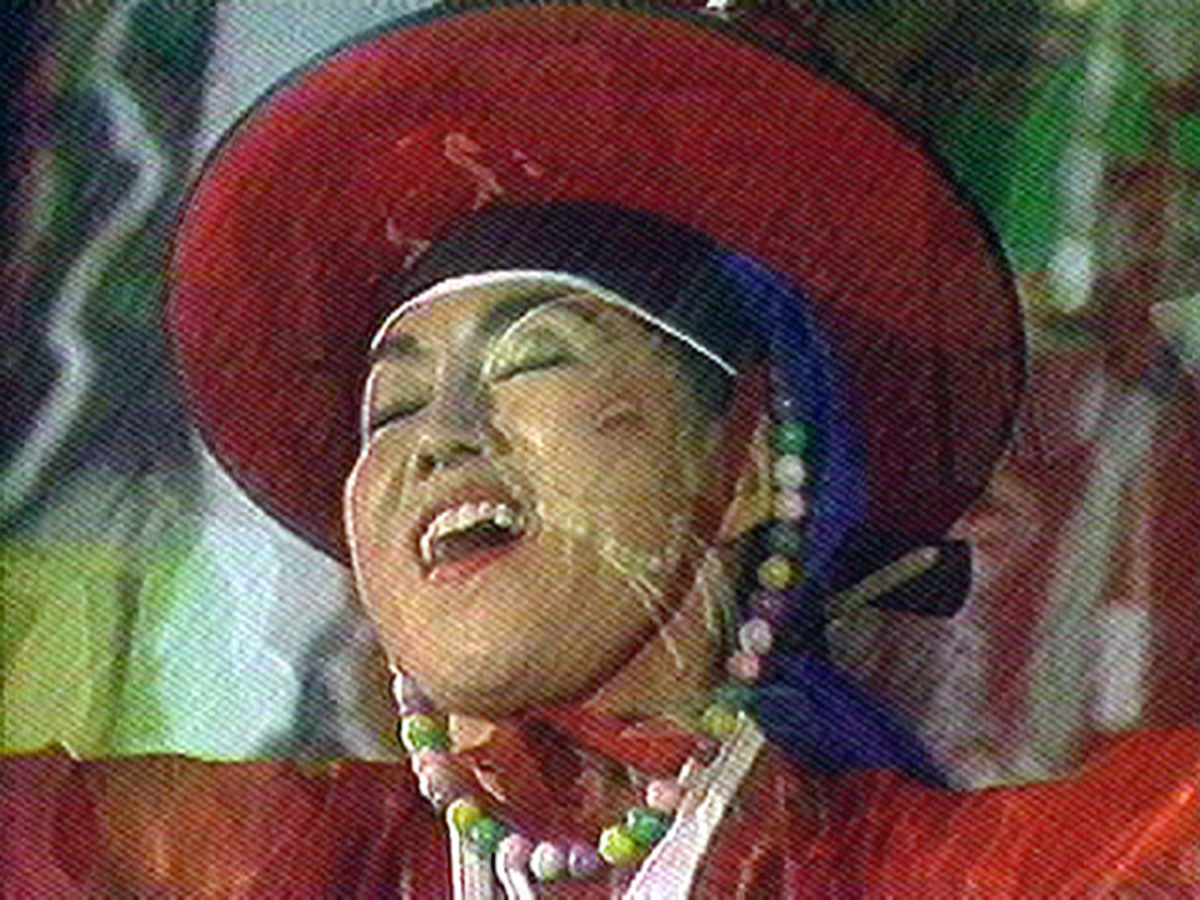

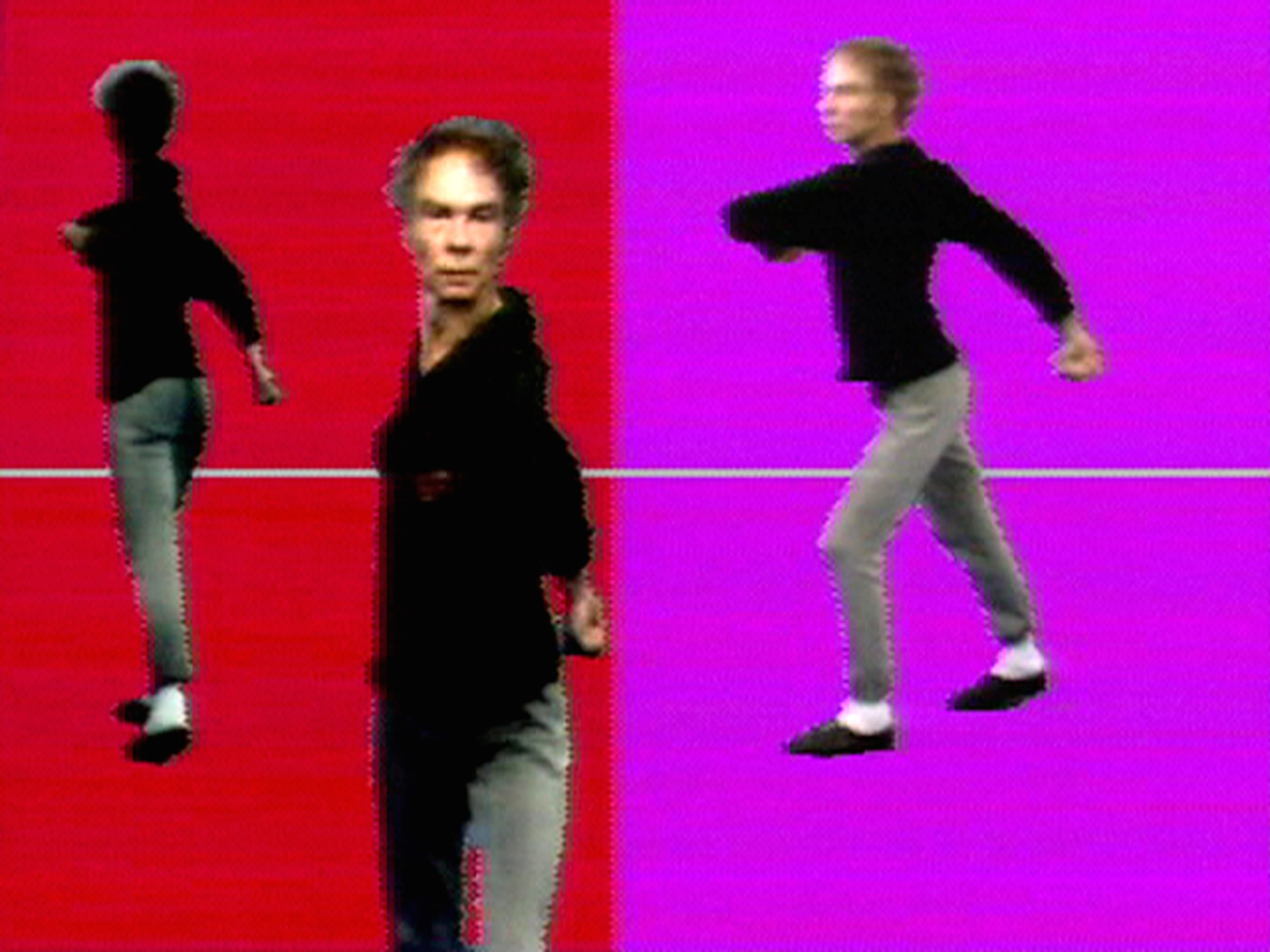

- Nam June Paik, Bye Bye Kipling 1986.Courtesy of Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York and the Estate of Nam June Paik

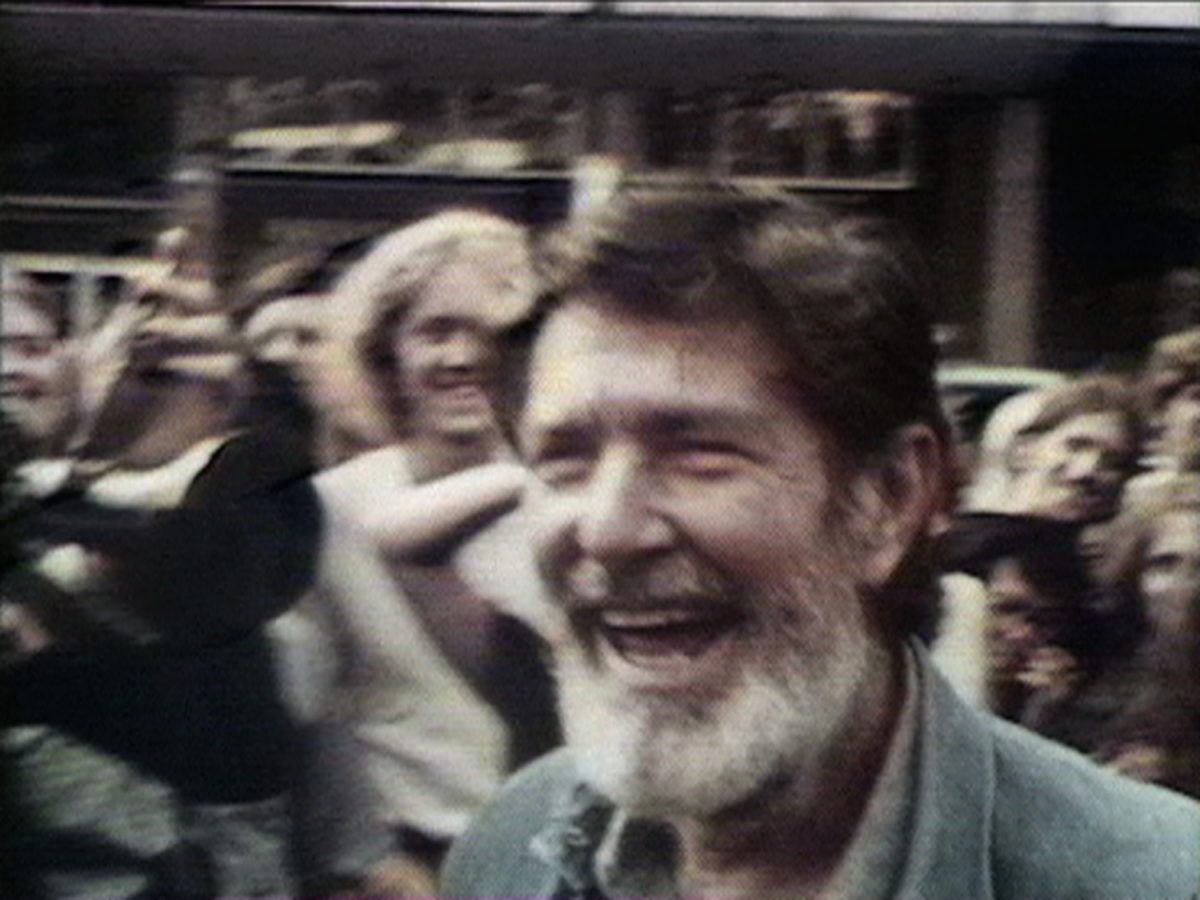

- Nam June Paik, A Tribute to John Cage 1973-76. Courtesy of Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York and the Estate of Nam June Paik

Television as both medium and “motor”: prefiguring post-internet art, and the brand language of MTV

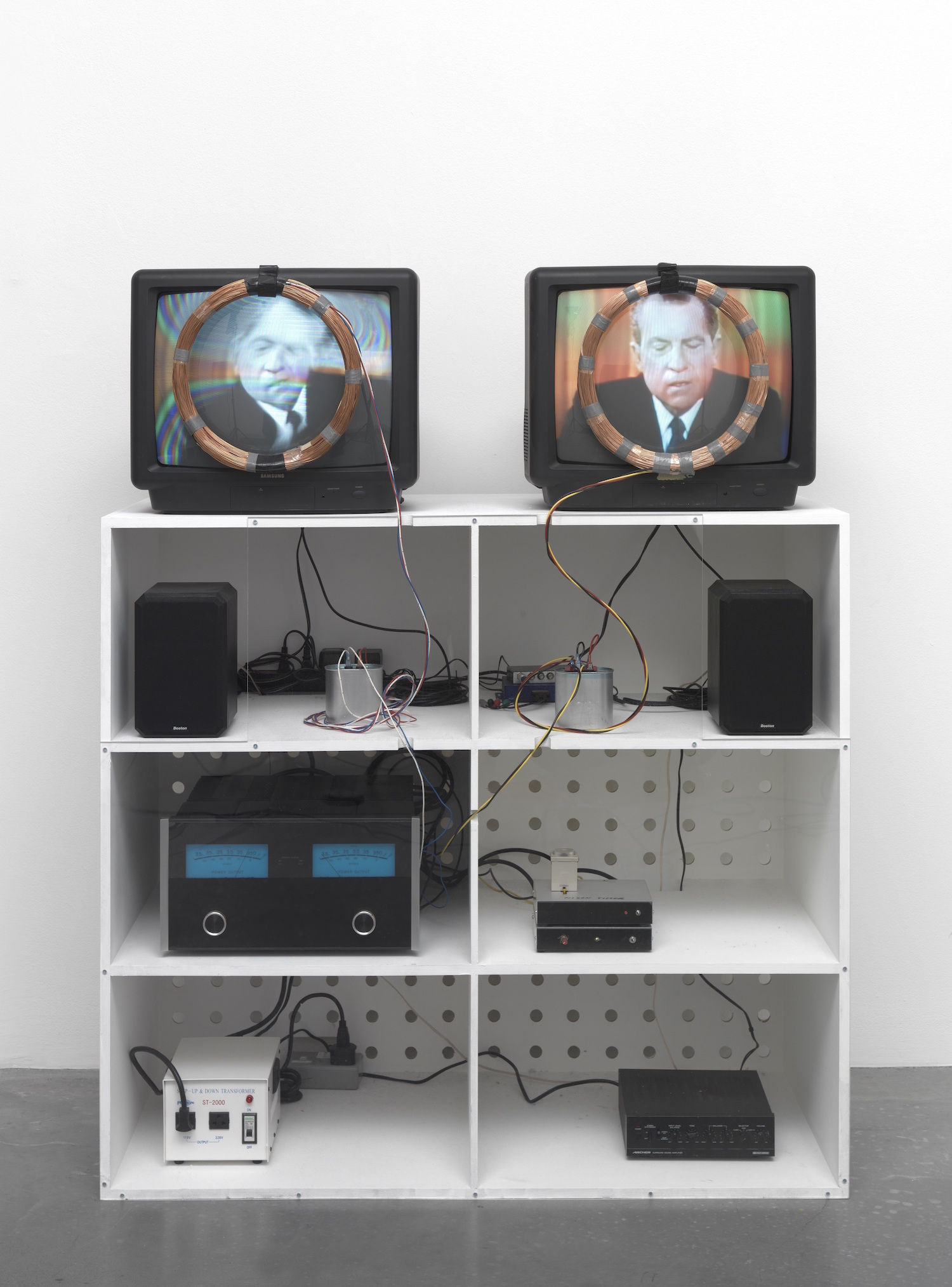

Paik’s first solo show, 1963’s Exposition of Music – Electronic Television, debuted his experiments with TV sets as an artistic medium. He openly acknowledged the influence of experimental filmmaker Karl Otto Götz, although the German artist was “coming from the perspective of turning technology into traditional media,” says the show’s assistant curator Valentina Ravaglia. Paik was interested in “tireless experimenting: any kind of technology he could mix and mash up, he would.”

While other artists of the time also worked with television, Paik stood out by using it as more than just material, as “the motor driving the work forward,” says Ravaglia. TV became more than just a unit with which to deploy work, but a work in itself—at once a sculpture and an experience, and a way of subverting assumptions around what a television is, and how and where it can be used.

Paik’s strange mashups of images and sounds; the personal and political; still images and rapid kinetic ones feel as current in today’s visual landscape as ever. This is evident not only in post-internet art, but even more so in the commercial worlds of identity design and motion graphics that frequently look to the grainy, glitchy aesthetics of the ninetis (much of which is thanks to Richard Turley’s 2015 MTV rebrand). Paik’s work exemplified this aesthetic long before agencies focused on buzzwords such as “millennial-focused online brand touchpoints”; Paik created it a good two-decades before the internet even existed.

“Paik’s strange mashups of images and sounds feel as current in today’s visual landscape as ever”

Using the language of mass media as a “trojan horse” for socio-political messages*

Paik’s work frequently used mass media communication in radical new ways to distribute ideas through channels usually associated with pop culture or domestic TV-watching. “He was interested in the humanising of technology and to take it away from its more utilitarian uses, such as CCTV. He was acutely aware that many of the technologies he was using were first developed for military purposes, and understood that mass media was an important way to address issues in a potentially very democratic way,” says Ravaglia.

“He believed that artists working together with engineers and using technology not just as an artistic medium, but as a societal tool, could contribute to a future where art and technology, science and spirituality could come together in a more holistic way—we’ve seen a shift towards that with contemporary artists, using technology as a strategy for research to find new ways forward.”

Paik was behind some of the earliest video art created specifically for TV, including 1970’s improvised, distorted collage Beatles Beginning to End, created using the

Paik-Abe Synthesizer. He also took advantage of TV’s capacity to cross geographical boundaries, hinting at potential dystopian possibilities in the not-so-subtly-titled Good Morning Mr Orwell aired on New Year’s Day 1984 (yup, 1984) across New York, Paris, Korea, the Netherlands and West Germany. “Paik subtly used the language of mass media—he still wanted people to watch them like a form of entertainment—but used them as a Trojan horse to to expose people to certain aspects of culture, but without imposing on them.”

Predicting new media obsolescence, internet culture, the YouTuber boom, and the birth of person-as-content

Paik’s ideas around the transmission of information proved eerily prescient: the artist coined the phrase “Electronic Superhighway” as a reference to a decentralized worldwide information exchange system. He also inherently grasped emerging media’s potentially rapid obsolescence: “He understood that video was soon going to be replaced by something else, and saw it as part of a unified digital landscape,” says Ravaglia. “He paved the way for how younger artists today approach making art with technology in a way that’s scalable—incorporating it not just as the artistic medium and material, but as the core of the idea.”

According to the show’s senior curator Sook-Kyung Le, Paik also posited that video could be intensely personal (the artist often included subtle autobiographical details such as his birthdate in his work, as well as more overt uses of childhood photographs), rather than governed by elite, unseen corporations or a state-sanctioned minority—and believed that, one day, everyone would have their own television channel as a means of expression. Fast forward to 2019: Instagram Stories, social media influencers and YouTubers. He was definitely onto something.

“Paik also posited that video could be intensely personal, rather than governed by elite, unseen corporations or a state-sanctioned minority”

Nam June Paik, Nixon 1965-2002. Tate, Purchased with funds provided by Hyundai Motor Company

Bringing sex and fun to stuffy, “serious” classical music

Paik had formally studied studied musicology at Munich University; where his multidisciplinary approach to art-making was catalysed by meeting composers Karlheinz Stockhausen and John Cage; and conceptual artists including Sharon Grace and Joseph Beuys who worked with new ways of visually scoring and performing music.

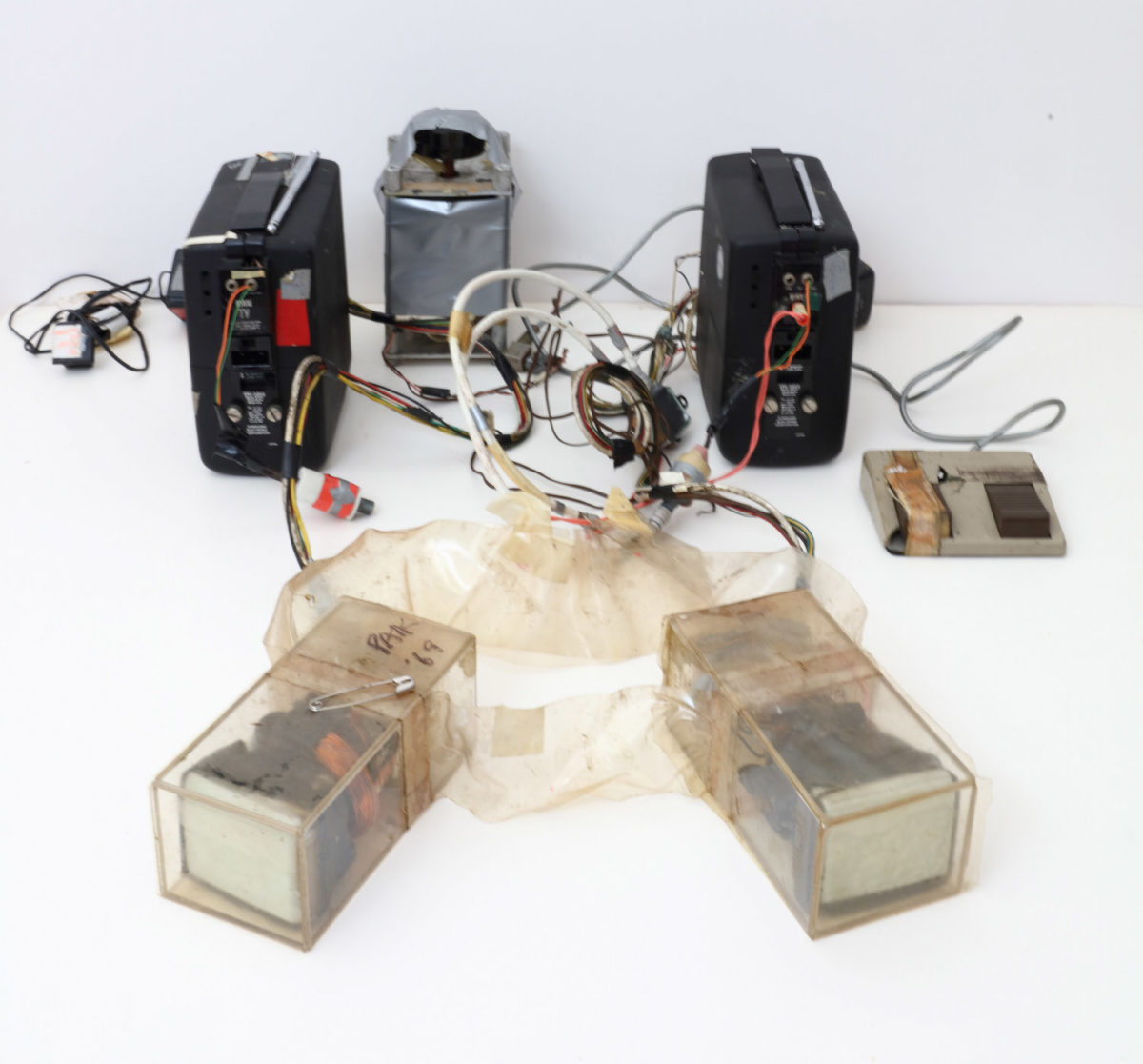

Looking to shake up the inherited formalities of classical music, Paik’s decades-spanning collaboration with cellist Charlotte Moorman used sexuality and a new kind of corporeal energy in performances. Moorman often played cello nude or partially dressed, or the pair played people as instruments themselves. In 1967, Moorman was arrested on charges of public exposure, much to Paik’s outrage, and he responded by creating a series of sculptures between 1969 and 71 including TV Bra For Living Sculpture, TV Cello and TV Eyeglasses, using elements used by Moorman in performances as costumes and props.

The idea was to “show that humanity could coexist and even partially merge with technology”. Again, a prescient prefiguring of contemporary discussions around transhumanism or “Human 2.0”. In more simplistic, less sci-fi terms, Paik wanted to make serious music sexy: as he said in 1967, “Why is sex, a predominant theme in art and literature, prohibited ONLY in music?”

Creating “interactive” and “immersive” art, long before they entered the Time Out buzzword lexicon

Paik’s 1963 Exposition of Music – Electronic Television show not only debuted his TV experiments, but also ambitiously invited active audience participation through works such as Foot Switch Experiment, which allowed audiences to alter a picture on screen in realtime by triggering a switch. Such pieces feel commonplace today, accustomed as we are to art that uses generative tech and AI; but almost sixty years ago, this was a radical move.

The most striking soothsayer of today’s obsessions with immersion is blasted out with Tate’s restaging of Paik’s Sistine Chapel for the first time since its creation in 1993. The piece uses thirty-four projectors to create a bombastic, all-consuming kaleidoscope of images and sounds across walls, ceilings and visitors. It places us right at the centre of Paik’s aesthetic, alongside collaborators like John Cage and the pop culture icons of the time such as David Bowie and Janis Joplin. It’s a joyous, spine-tingling experience and (rather ironically) throws a massive shroud of shade over the proliferation of the tedious “immersive” experiences that brands and art institutions alike are so rampantly peddling today.

*Paik was by no means the first artist to use television in these ways (Peter Weibel and Valie Export worked with TV “interventions” on an Austrian public service broadcaster from 1969; and Chris Burden purchased TV ad time in the early 1970s to broadcast his surrealist ”commercials”). These artists prefigured later artistic public TV interventions aiming to push political ideas like feminism, or that signalled the sinister possibilities of digital surveillance and slapped them into the domestic sphere: the 1987 Max Headroom broadcast signal intrusion, for instance; or early nineties Cyberfeminist Art such as VNS Matrix, who stated their intention to disrupt the “virus of the new world disorder” and sabotage “big daddy mainframe.”