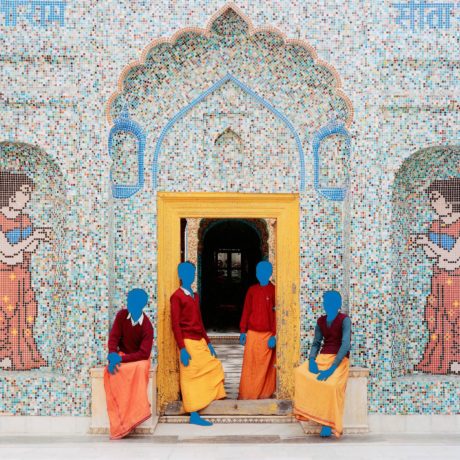

On first appearances, Vasantha Yogananthan’s AMMA series may appear as a standalone body of work: stylised mixed-media photographs showing bright scenes of life on the Indian subcontinent—a hyperreal tonic to the documentary images which often characterise the region. Domestic scenes layered with brightly-coloured paint, they are uncomplicated and seemingly apolitical. In some images where a single object or figure dominates, they’re prominently positioned so the viewer can appreciate the pigment upon the surface undistracted. In others, buildings are captured in their clean symmetry, gentle blues and whites the welcome colours of open skies behind. But light as it may appear, AMMA is framed at every turn by the weight of Indian mythology. The series, recently on show at The Photographers’ Gallery, London, is the closing chapter of Yogananthan’s seven-part photographic project A Myth of Two Souls (2013-2020).

The artist’s ambitious undertaking was inspired by The Ramayana, one of the three narrative pillars of Hindu spiritualism. Dated around 500 BCE to 100 BCE, Valmiki’s Sanskrit epic tells the story of Prince Rama of Ayodhya, who, after his father has been cursed years before, is banished from the kingdom and forced to spend 14 years in exile, accompanied by his wife, Sita, and brother, Lakshmana. Forced away from the city after one of the King’s wives pressures him into banishing his heir, Sita is abducted from the forest by Ravana, the 10-headed, 20-armed demon-king of Lanka. Rama assembles an army of monkeys and bears to search for his wife, resulting in Ravana’s death and Sita’s liberation and return to her husband. After 14 years, Rama, Lakshmana and Sita return to Ayodhya, welcomed by the people with a festival of light.

“Yogananthan has traversed the Indian subcontinent in order to capture the tale’s endless resonances in everyday life”

Instead of being guided by the story, which centres on incarnate deities, moral tests and elaborate exclamations, Yogananthan has traversed the Indian subcontinent (much of the original story takes place in modern-day Sri Lanka) in order to capture the tale’s endless resonances in everyday life, both obvious and unseen. The first chapter of A Myth of Two Souls, Early Times, focuses on Rama’s youth, allowing the artist to shoot portraits of young boys or children playing together, the misty early mornings lending an ethereal feel as the characters are introduced.

In an image titled The Fishermen he uses a documentary style, showing livelihoods in motion, coupled with overpainting on the photograph. Yogananthan’s experimentation with painting and alteration of his images enables him to invite the Ramayana’s mythical elements into his work. The acrylic gouache used in this image represents a dramatic intervention by the artist, obscuring the subjects’ faces where before they stood to populate the narrative. Perhaps, as a group rather than representations of Rama, Sita or Lakshmana themselves, their blocked-out faces represent mortal insignificance compared with the clarity of godliness.

“The artist’s seven years of work have been a practice of social exploration: capturing the diversity of the continent’s population as they exist in reality”

This is a story that has been told and retold over the generations. In Srimati Kamala Subramaniam’s 1995 English language text,

an observant third-person narrator constructs a didactic, obedient Sita. Upon discovering Rama’s impending exile on his coronation day, she says that, “For the woman the husband is the only refuge and not her father, nor her son, or her mother, or her friends nor even her atman in this life.” As part of his project, Yogananthan has commissioned an accompanying text by a number of Indian female authors for each of the seven chapters. These redress the gendered framing, repurposing snippets of the Ramayana from Sita’s perspective.

AMMA’s text, available in March 2021, will illuminate further how Yogananthan has integrated his subjects into the story. The artist’s seven years of work have been a practice of social exploration: capturing the diversity of the continent’s population as they exist in reality; hinting at the mythical underpinnings of Indian cultural life while never referencing it directly in each image. He invites us to consider The Ramayana as a guiding, connective presence hidden across these vast regions.

Vasantha Yogananthan, AMMA

The Phtographer’s Gallery, London (temporarily closed due to Covid-19)

VISIT WEBSITE