In a ‘Terminal Note’ to the posthumously published Maurice (1971), E. M. Forster wrote that his novel ‘belongs to an England where it was still possible to get lost. It belongs to the last moment of the greenwood…Our greenwood ended catastrophically and inevitably.’ Within the context of Maurice, the greenwood exists as the locus of unrestrained queer desire, a rural utopia in which the eponymous hero can love and live as he longs to. Having grown up on the very outskirts of the New Forest, I have long been thinking about this idea: the forest as a safe haven, a space unfettered by modernity or social constraint. I could so easily lose myself in the sprawling heathlands and thick clusters of pines near my house, free to do as I like. Now, in a world that seems determined to take this away, I long for that feeling more than ever.

In August, I came across a compact, spectral-looking glass and rock sculpture by Rachel Rose at Pilar Corrias’ Interflow show. I had moved to London less than three months beforehand and was adjusting to the intense swell of summer heat. My hometown has a thick river running through that, on days like these, my friends and I swim in (though there was some contention about whether we are allowed to do this, we still swim there anyway). In search of refuge in London, I turned to the Hampstead Heath Ponds where – unlike the New Forest – I didn’t have to worry about trespassing by virtue of a bizarre legal technicality.

The enduring charm of the Ponds tells of how few inland waters there are in Britain to legally swim in. In England and Wales, public access rights exist for less than two per cent of rivers, and only three per cent of the land is designated as common land, accessible to everyone. The borders of the forest seem to get smaller every time I go back to my parents’ – that possibility of my own greenwood vanishing inch by inch.

Reencountering Rose’s work at that point had felt serendipitous. I’d first seen her work at her solo show Enclosure, also at Pilar Corrias, the year before. So named after the exhibition’s titular video, the magical realist film delves into the impact of large-scale privatisation on common land, marking the pivotal shift in England from a feudalistic to a capitalist society. Its narrative unfolds around an imagined cult-like clan of land grifters known as the Famlee, led by the hustler Jaccko, who swindles people into selling him deeds to their land. Spotlit next to the film, the paintings in Rose’s Colores series present altered reproductions of landscapes by Gainsborough, Wright, Palmer, Constable and more, pastoral idyll ruptured by chaos. Colore (1845) (2022) reimagines Francis Danby’s Hampstead Heath (1845) as an arcane enigmatic palimpsest. The sun becomes a black hole – the heath, the site of an oil spill-looking disaster. Through material surrealism, Rose’s artistic practice – her sculptures, paintings, film and photography work unearths the ecological turmoil brought on by capitalism, industrialisation, and private land ownership.

Before moving to London, I’d (naively) never really given these ideas, or their direct impact on me, much thought. I’d taken for granted the abundance of woodlands, lakes, and beaches that I’d been surrounded by for most of my life; only without them could I fully appreciate what I was missing. And when autumn hit, I longed for them even more. I loved the city but longed for the time and space to breathe, to be still – things that, in the darker, colder months, are spartan in cities like London.

Around that time, I learned that a lake – only a short walk away from my parents’ house – had been fenced off from the general public. This lake was the site of countless core memories – the place where I’d posed for photos with my newborn brother, where two of my closest friends (now married) got together properly, and where, as teenagers, three of us had rode an inflatable two-person canoe across the water (unknown to us then that the lake was thirteen feet deep and a disused quarry). You can still walk around it but the water itself is out of bounds, now guarded by dense shrubbery and a metallic green gate, but it’s not the same. When Labour announced a U-turn of its earlier promise to create a Scottish-style right to roam in October, it was the final straw. I found myself thinking of Rose’s work again and again. What was left of Britain’s common land? Where is the greenwood now?

Wild waters have always inspired a kind of ferality in me – I think that’s why I’ve made a habit of going back to them again and again. It’s also why I feel so adrift in winter when nature feels more hostile than it does welcoming. When I found myself missing the forest more than ever that December, I didn’t then expect to find that kind of earthly magic in a gallery.

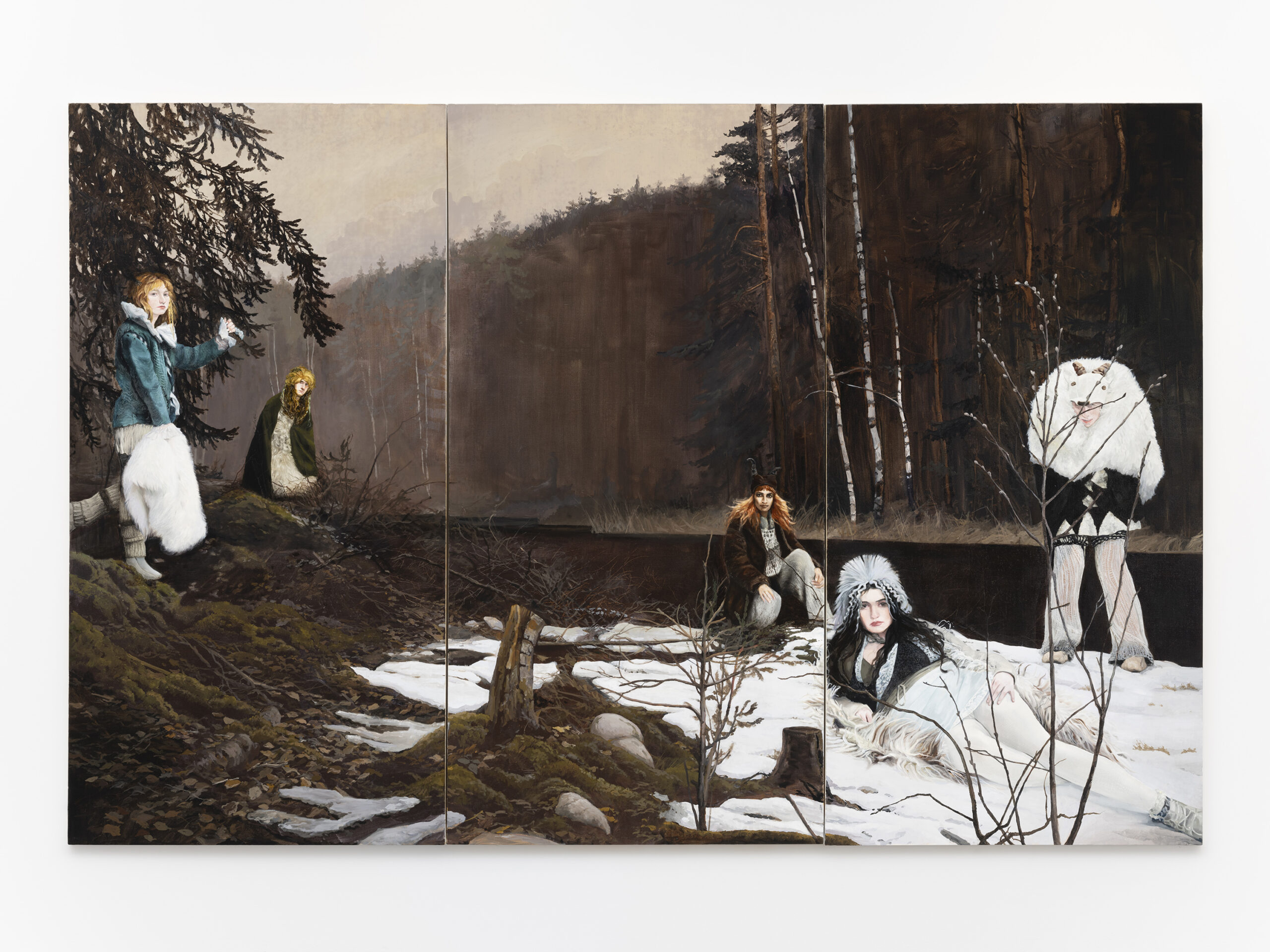

Through birdsong and woodland soundscapes, Paulina Olowska’s Squelchy Garden Mules and Mamunas brought the forest to life for me. Images of silver birches, mushrooms, foxes and deer populate her paintings. Women communing amongst themselves, with the viewer, with the wild woods around them; the Mamuma, a sinister swamp demon from Slavic folklore, reimagined as sprightly and androgynous nymphs. Here, Olowska’s work is a subversion of traditional depictions of female mythological creatures – more than that, it’s a lot of fun. Paintings like Tetchy, Mokosh and Friends and Dziewannas (After Branislav Šimončík) (all 2023) conjure up memories from my childhood: climbing trees and playing in streams. Though I’ve seen a lot of art that has the ability to move me in some way or make me think differently about the world, no artist has ever made me feel nostalgia like Olowska.

Together, Rose and Olowska are artists who define nature through the feminine, fertile explorations of land and its infinite possibility for magic. Although each artist engages with it in their own way – Rose’s work reads more like an ecological intervention, while Olowska inspires something more light-hearted and whimsical – both remind me of where I’ve come from and my gratefulness for that. While I love London, that doesn’t change the fact that I miss the woods, and I’m plagued by perpetual anxiety about climate change and land privatisation. All I can say is that I’m thankful their art makes me feel less alone in this and that their work can stand as a reminder of what we stand to lose.

Written by Katie Tobin