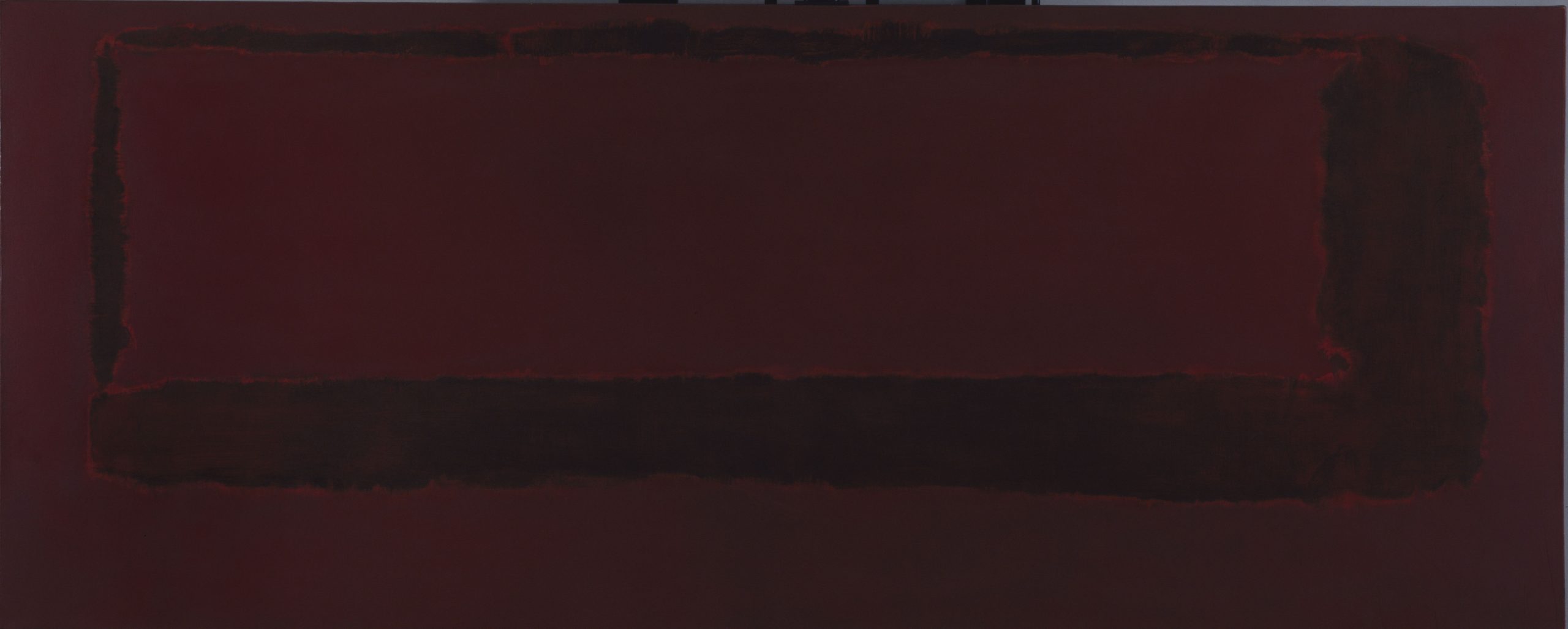

Sometimes it’s crimson, the colour of fresh blood. Then it’s darker, deeper, a sort of rust that’s halfway to brown. At other times it might appear black on first glance, but if you get close enough, stare for long enough, it’s still red.

I can’t be sure when I first saw my mental illness with this sort of clarity, as there are so many gaps in my memory (the human brain is hard-wired to self-destruct in that way). But I can say now, with no uncertainty: red. All the agony and the self-destructive impulses, all the hatred and hurting that gave way eventually to a sort of numbness that settled deep in the marrow: red.

“I noticed patches where the paint was discoloured or disturbed, like the different shades of broken capillaries in a bruise”

I suppose it’s no surprise I was drawn to Mark Rothko’s Seagram Murals the very first time I saw them at London’s Tate Modern, with their deep ochre and vermillion hues. The dark canvases towered above me, stark lines radiating an aura of bleakness. The longer I looked, the more I noticed: brush strokes, scratches, patches where the paint was discoloured or disturbed, like the different shades of broken capillaries in a bruise. These paintings seemed to ache.

I was a recent transplant from the north of England, unmoored from family and friends and isolated in a city not yet my home. Seeking the sort of collective distance that comes in large, busy public spaces, I took advantage of having easy access to museums and galleries for the first time in my life. I understood the bleakness I saw in Rothko’s paintings.

Growing up, my understanding of art was largely limited to what I saw on television or learned in our weekly art class at school. While I could appreciate the Monets and Van Goghs I was told with authority were masterpieces, my understanding of art was severely restricted by the limited view that this education offered to me. Art was part of a world I didn’t belong to.

When I first moved to London, my excursions to galleries and museums were out of necessity more than anything else. I had very little money and worked long hours; the free time I had I wished to spend anywhere but my small room in a six-bed shared house. I would take the bus to central London at the weekend, and stand shoulder-to-shoulder with tourists staring at stolen artefacts and pieces of art donated as tax write-offs. Paintings barely larger than a sheet of paper had an assigned value so astronomical that it didn’t seem like a real number to me.

I was acutely aware of the strangeness of it all. London is a city of vast wealth inequality, and while I adore its atypical policy of broadly not charging entry to museums, you become strangely dispirited when you realise how little your life is worth compared to a painted canvas. Then again, perhaps that was the despair talking.

The Seagram Murals were exhibited in a dark room, separate from the rest of the gallery. The darkness is what initially caught my attention: galleries are usually typified by their white walls and stark lighting. The plaque on the wall explained the low light was to help preserve the pigments in the paints. It was to help preserve the red.

Commissioned in 1958 by The Four Seasons, they were originally intended to serve as the centerpiece of the two dining rooms in their new New York City restaurant in the Seagram Building. Wealthy diners could enjoy some fine art while they ate and drank. Rothko was to be paid $35,000 to create around 600 square feet of murals. It was his first commission.

The reasons that Rothko took the job are contested, though the artist himself claimed in a 1959 interview: “I hope to ruin the appetite of every son of a bitch who ever eats in that room.” After a trip to Europe in 1959, Rothko returned to New York and dined at the Four Seasons, ahead of finishing his paintings. It turned out to be an illuminating, and infuriating, experience. “Anybody who will eat that kind of food for those kind of prices will never look at a painting of mine,” he fumed to an assistant.

He cancelled the commission. The paintings went into storage. Eventually a number of them were bequeathed to the Tate Collection. Rothko hoped they might one day be exhibited in a gallery next to the works of JMW Turner, his greatest artistic inspiration. This wish would be granted: the Seagram Murals now reside in the Tate Britain, directly next door to the rooms which house the Turner collection.

“Rothko’s paintings opened my eyes. This was the first time I truly felt an emotional connection with a piece of art that wasn’t a book or a film”

The creation of the Seagram Murals was reimagined in Red, a 2007 play by American writer John Logan, in which Rothko and his fictictious assistant Ken work in his studio to complete the commission. Despite the play itself receiving a mixed reception, Alfred Molina was widely acclaimed for his portrayal of Rothko. I saw the play’s London revival in 2018, which deepened my affection for the Seagram Murals.

In particular it highlighted for me the class politics so present in their creation, notably Rothko’s decision to withdraw the paintings and instead donate them to an institution which makes art accessible for millions of visitors every year. I believe that art is for everyone, and it’s shameful that so many masterpieces languish in inaccessible private collections or bank vaults, rarely if ever seen in the way they were originally intended.

My encounter with Rothko’s paintings, displayed in their intended manner as the artist would have wished it, opened my eyes to a world I had previously written off as beyond my grasp. This was the first time I truly felt an emotional connection with a piece of art that wasn’t a book or a film. The Seagram Murals, looming and austere on the walls of the Tate, have remained thrilling to me in their strange, unknowable darkness. If I stare for long enough the colours shift and bleed, provocative in their simplicity and starkness.

“Rothko died by suicide. As someone who has fought the impulse to end my life multiple times, I often feel an affinity to artists the world has lost in such a manner”

On 25 February, 1970, Mark Rothko died by suicide at his studio. That same day, the Seagram Murals arrived in London for exhibition. There is no deeper meaning in this coincidence I’m sure, but as someone who has fought the impulse to end my life multiple times, I often feel an affinity to artists the world has lost in such a manner.

The Seagram Murals reflect back to me an ongoing struggle with my own mental illness, and their curious origins reflect a desire for art to be more than numbers in a bank account. I struggle with my despair, with the great redness I see almost every day of my life, but I accept now that art, at least, makes the despair a little more bearable.

Hannah Strong is a freelance writer focusing on film, television and pop culture. She is the digital editor at Little White Lies

This Artwork Changed My Life

Absorbing personal stories of the lasting impact that art can have

READ NOW