A collateral show at the Venice Biennale, the exhibition surveys the cultivation of traditional agricultural practices, rituals and crafts as essential to the survival of Palestine’s endangered people and history

Still and moving images of people and vegetation hang side by side in a symbolic conversation in SOUTH WEST BANK: Landworks, Collective Action and Sound (through November 24), a group presentation co-produced by the NGO Artists + Allies x Hebron (AAH) in collaboration with the Bethlehem’s independent cross-disciplinary project Dar Jacir for Art and Research. On view on the ground floor of Palazzo Contarini-Polignac as part of the collateral events programme of the 60th Venice Biennale, the showcase highlights, among other things, the interconnectedness and shared destiny of Palestine’s human and plant lives as the ‘produce’ of the same besieged land. It does so by weaving together artistic expressions emerged during residencies hosted by either one of the organising institutions.

Besides wall artworks, the wooden and rough brickwork spaces of Magazzino Gallery – an unpretentious warehouse situated at the foundation of the historic Venetian palace – are filled with olive oil tins, bottles of wine and flour- or dirt-based installations which hint at the country’s ancestral agricultural practices and the unwritten traditions that shape its everyday. Embodying Palestinian livelihoods, these ordinary goods are more than objects. When looked at in tandem with the photographs, films, writing and textile pieces garnered in the exhibition, and considered in the context of the violence perpetrated by Israel in the Occupied Territories and Palestine as a whole, they become acts of resistance. If it is true that to eat, to drink, to till the soil, to preserve customs, to dance, to write and to create is to exist, then SOUTH WEST BANK turns to art to visualise the heterogeneity of Palestinian existence in the face of ongoing cultural and physical erasure.

In the show, “dance, song, fable, group activity and sensory narrative all merge,” curator Jonathan Turner tells me over email on the eve of its opening, which, scheduled for April 19, coincided with the press preview days of the Biennale. “There is a clear dialogue between the work of the different artists, a tangible collective spirit strongly based on the concept of resilience, but also of inherited joy.” Bringing together a wide selection of Palestinian and international creatives, the presentation zooms in on artworks developed in the Southern West Bank, “an area whose cultural activity has often been overlooked”, in a suggestive encounter between multiple artistic languages, personal and communal histories as well as rituals.

Like most countries bordering the Mediterranean Sea, Palestine relies significantly on agriculture: olive groves and vineyards have been cultivated in the region since the 2nd century AD, when the territory was under Roman rule. Decades before Al Nakba – the mass displacement of Arab Palestinians at the hands of armed Zionist settlers aiming to establish a Jewish state in the country in 1948 – the population’s ability to tend crops had already been hindered by restrictions and taxes imposed on native farmers by colonial Britain during the British Mandate (1920-1948). The establishment of more Jewish settlements and land purchases by Zionist organisations worsened the situation, drastically reducing Palestinians’ access to, and preservation of, farming infrastructure, let alone the profit derived from it. Addressing the implications of decades of Israel-enforced territorial, military, economic, bureaucratic, movement, legal and political control, SOUTH WEST BANK sees local artists and their allies recount the reality of this portion of the Occupied Territories on their own terms.

Dealing with land, agriculture and heritage in an under-threat, ever-morphing topography, the exhibition ponders “how cultivation can embrace planting, harvesting and culture in itself,” Turner explains. It is a message that rings loud in the olive oil and wine produced in the South West Bank by Baha Hilo and Sari Khoury respectively, both displayed in the show, a testament to “their tenacity in ensuring that, despite reduced yields, they continue to work the fields even under duress”, adds the curator. Similar tropes recur in the contributions of artists Adam Broomberg – co-founder of AAH, which he leads alongside Palestinian activist Issa Amro – and Rafael Gonzalez: the two have created a monochromatic series of portraits of centuries-old olive trees whose survival is compromised by the building of new fences, encroaching settlers’ homes and the difficulty of local growers to access their orchards and meadows. The fruit of an eighteen-month shooting process, the collection has recently been released as a photo book, titled Anchor in the Landscape, by MACK.

One of the images part of the project captures the Al Badawi olive tree, “a 4,500-years-old, 12-metres-high exemplar yielding over 800 kg of olives every two years,” Broomberg tells me over a crackling phone line on the install day of the exhibition. To stand under “this thing,” he explains, is an experience like no other. “Just think about that timescale, 4,500 years,” Broomberg says. “That is more than double the time [that has passed] since the birth of Christ. Now consider the number of empires that have come and gone since then – this tree has outlived them all. Yet, only between 1967 and today, 800,000 olive trees have been destroyed by Israeli authorities and settlers.” For the Berlin-based South African artist, who is the son of a second-generation holocaust survivor and “ardent Zionist” and was educated in Jewish schools, these plants are not just a symbol, but carry invaluable “economic, cultural and juridical significance.”

Under Ottoman and British Mandate laws – two of the legislations impacting land ownership and rights in Palestine and Israel together with Jordanian and Israeli regulations – continuous cultivation of olive trees can be used as evidence of land use and potentially support claims of ownership or customary rights of specific estates. To put it simply, plants and crops legally belonging to Palestinians make it harder for Israeli colonisers to expand their settlements as they bound the natives to their roots, as much physically as metaphorically: in this context, “getting rid of olive groves becomes, effectively, a military strategy to eradicate the existence of a people,” Broomberg concludes. Exile and extinction are themes also conjured by Jumana Manna’s Foragers (2022): largely focused on the collecting of wild artichoke and thyme in disputed territories, this audiovisual piece exposes how personal histories are affected by prohibitive laws through a “meditative pace and wry humour”. “What protected species?”, an elderly man exclaims towards the end of the film’s trailer. “This land isn’t yours! Neither is the plant!”

Food, intended as both nourishment – source of life – and the cultural rites revolving around it, is another one of the subjects examined extensively in SOUTH WEST BANK. Artist Shayma Hamad’s photographs, performances and the making of her hand-made “dough-balls”, for example, “highlights the basic similarities in the physical acts of kneading, ploughing and digging,” explains Turner. At Magazzino Gallery, she presents a recipe booklet which draws a parallel between death food rituals and the act of digging in Bethlehem. Speaking of the artwork over email, Hamad tells me that, through this juxtaposition, she intends to raise questions of ownership and belonging aimed at investigating events of death and loss in Palestine. Paying particular attention to Palestinian women’s experience of mourning, her artwork reveals how, in this setting, “food becomes a means of prayer and wishing,” Hamad writes.

In Arabic, the word naqisa means ‘missing.’ This ‘missing,’ the artist explains, is always present in times of death; it is conveyed by the absence one feels after losing someone dear to them, by their non-existence. To help the deceased’s family process the pain triggered by this condition, Palestinian women gather “to knead various types of dough using flour – wheat being considered sacred – collectively remember the person who passed and invoke the spirit of wnesa, or the ‘comfort’ we find in companionship.” The idea behind this practice, Hamad says, is “to make the bereaved feel surrounded by the familiar, to have them perceive your presence in the void.” Promoting togetherness and encouraging public participation, the artist’s contribution to the show amasses recipes “from women who dig up a place for the dead with their dough, whether in their hearts or in the land itself, as it happens with ploughing before sowing,” she says.

One of the most notable aspects of SOUTH WEST BANK is that it not only spotlights the craft of Palestinian artists but also places them in dialogue with international allies, unveiling unexpected creative synergies and demonstrating the potential of empathy beyond borders. Though the exhibition explores the effects of the Israeli occupation on the Palestinian landscape, its aim, Broomberg explains, “is not to bear witness to conflict, but to celebrate the power of transnational collaboration”. Characterised by multiple cycles of creation and destruction, the focus of some of the projects on view are imbued with what the art educator and activist describes as a “regenerative nature”. It is the case of Turner Prize-winning Irish artist Duncan Campbell’s Nothing Impossible (2018) film, realised during his stay at Dar Jacir, which follows the reparation of a battered Peugeot 305, “a car quite prolific in the 1970s’ Occupied West Bank,” Broomberg says, in an echo of local people’s resilience.

Other artworks, like the audiovisual installations presented by Dar Jacir’s founding director, artist and filmmaker Emily Jacir, take the cooperative vision cherished by Broomberg centre stage by connecting only seemingly unrelated areas of the world through movement, sound and performance. “The films we included in SOUTH WEST BANK originate from more than six years of building, collaborating, exchanging and cultivating a large network of dancers and musicians between this fraction of Palestine and the South of Italy, institing on our shared Mediterranean heritage,” she tells me in a written email exchange. “This programme, including its inaugural appointment, Incontro tra la Pizzica e la Dabka, is a translation of shared encounters with agrarian, musical and dance traditions [from these two contexts].” In Wherever you sow grain, the grain grows, one of the pieces on display in Venice, “the artists witnessed the impossibility of reaching one’s own olive trees, the difficulty of harvesting, the longing to be on one’s own land, the history that binds the community together and the profound cultural heritage of the land,” Jacir explains.

A choreographic and musical performance led by Italian dancer Andrea De Siena and percussionist Luca Rossi, Wherever you sow grain, the grain grows, takes shape from the interaction between Bethlehem’s agriculture-inspired dance and music heritage and Campania’s own. Enacted collectively by a group of 13, it blends the dabka – Palestine’s traditional folk dance – with the timeless atmospheres evoked by the tarantolato and highly contagious rhythm of tammurriata, a popular Campanian dance informed by home and field work. “In both these traditions, the symbolic gestural aspect is connected to the relationship of the body with the land, exemplified by the castagnette (musical instruments made of olive wood which accompany the steps of the tammurriata dancers), the wrist movements that simulate the gesture of sowing and the arm movements used in cultivation,” Jacir writes. A thriving ground for artists, dancers and musicians, this collaboration has already left a mark on Bethlehem’s arts scene, prompting more organisations to engage in initiatives capable of furthering the conversation between these two choreutic and sound repertoires.

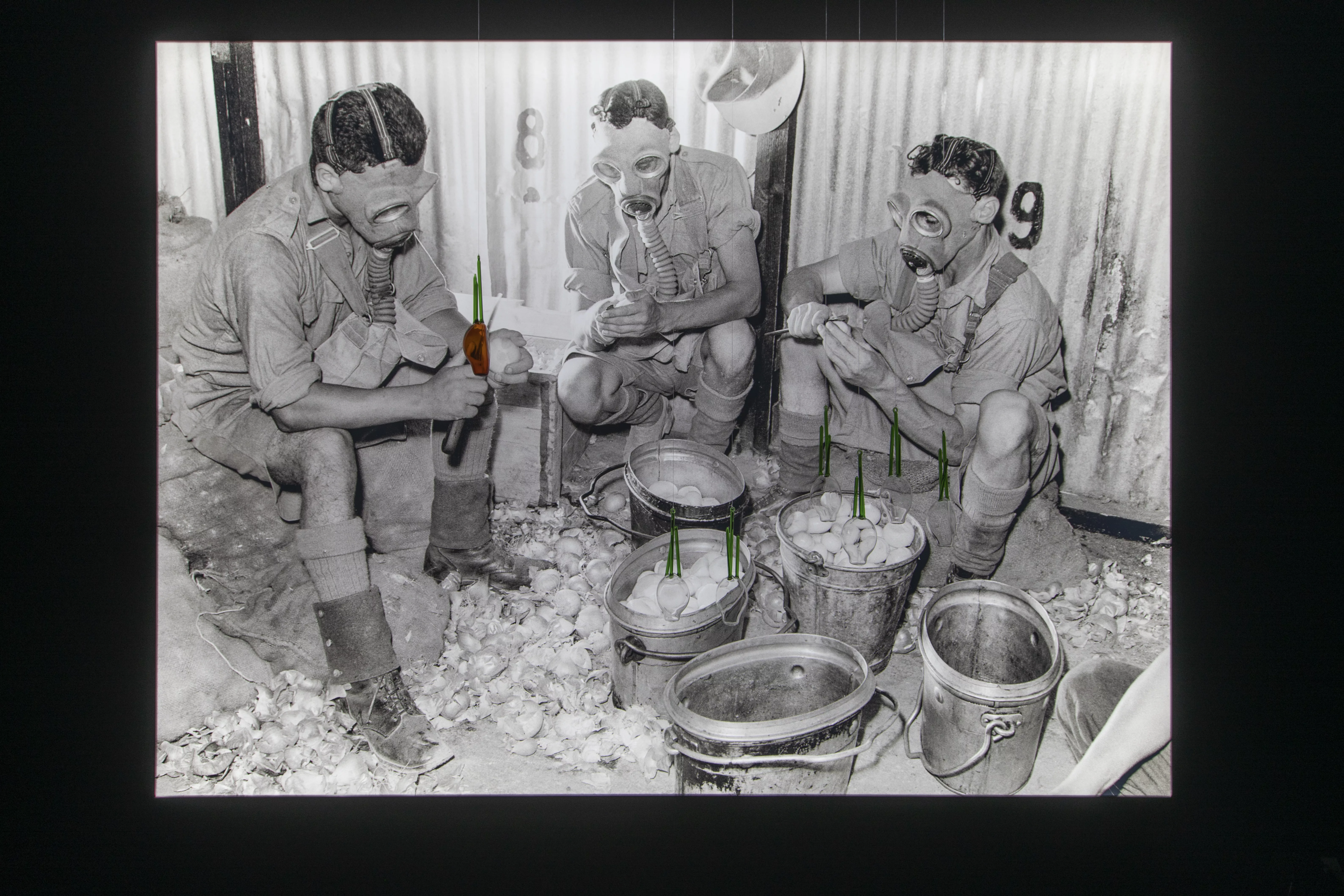

Architect and visual artist Dima Srouji and Women’s and Gender Studies professor Jasbir Puar, two more of the personalities spotlighted by SOUTH WEST BANK, have taken an image from their Revolutionary Enclosures (Until the Apricots) series to Venice. Part of a wider mixed-media project incorporating everyday artefacts into a thought-provoking retelling of Palestinian identity, memory and resistance, Untitled (2023) portrays three Australian soldiers peeling onions in gas masks during the British Mandate in 1940’s Gaza. A black-and-white archive shot, the photograph shows a floor covered in onion skins and metal buckets, offering a glimpse into the preparation leading up to army meals. Slowly swaying in front of the lightbox that frames it are seven hand-blown glass onions created by Srouji in Palestine. The contrast, of course, isn’t coincidental: establishing a comparison between the living conditions of the occupying military forces and those of the native population, the glass artworks “remind us that Palestinians use onion masks to protect themselves from teargas,” reads the caption accompanying Untitled.

Reflecting on her participation in the 60th Biennale Arte and this showcase more broadly, Srouji considers it necessary to set the record straight: “this isn’t contemporary art trying to make it big in the market,” she tells me promptly in an email. “This is […] a form of survival: working with collectives that are fighting towards Palestinian liberation feels like pushing against a dam and starting to see it crack. We are closer to liberation than people realise, and art allows us to visualise what that might taste like, besides materialising the catastrophic losses [we have endured] over 75 years.” That, to Srouji, is what Palestinian art has tried to do since day one of occupation. Today, “we are standing on the shoulders of generations of Palestinian artists,” she says.

It is a sentiment endorsed widely by Palestinian-American photographer Adam Rouhana, also featured in the exhibition. His spirited documentation of Palestine, Before Freedom (2022-), grants us a break from the devastation-driven media coverage of Israel’s ongoing attack on the country to restore the blissful vibrancy of its quotidian life, nature and ritualism, and honour the overlooked stories of its people. First appeared on the digital edition of Dazed in April 2023 and later landed on Aperture and The New York Times, Rouhana’s grainy, sun-soaked images of Palestinian existence have gone around the world: defying the censoring dynamics of social media algorithms, they have been re-shared by thousands of global allies as both a symbol of international solidarity and an emblem of the Palestinian fight for liberation.

If you have found yourself doomscrolling through your Instagram home recently, chances are you have come across the image-maker’s uplifting portraits of Palestine’s youngest generations. These include his ubiquitous shot of a teen savouring a slice of watermelon in an olive grove, which is part of SOUTH WEST BANK, and that of a child cheerfully running through an empty alley with a Palestinian flag waving from his back, the fingers of both his hands raised in a peace sign. Last month, Rouhana’s growing acclaim culminated in the launch of his debut solo exhibition at FRIEZE’s No. 9 Cork Street gallery in London, curated by arts and culture journalist Amah-Rose Abrams. Proving the urgency and resonance of his visual storytelling, Before Freedom Pt. 2: The Revolution Cannot Be Built On Dreams Alone – an expanded edition of that first show, developed in collaboration with curator Lobna Sana – has just been inaugurated at TJ Boulting, where it will continue through June 22.

Like the rest of the contributions collected by the AAH and Dar Jacir for Art and Research’s co-organised Venice presentation, “Before Freedom looks at the current moment we are in today in Palestine,” Rouhana tells me. “The moment before we are free.”

Words by Gilda Bruno