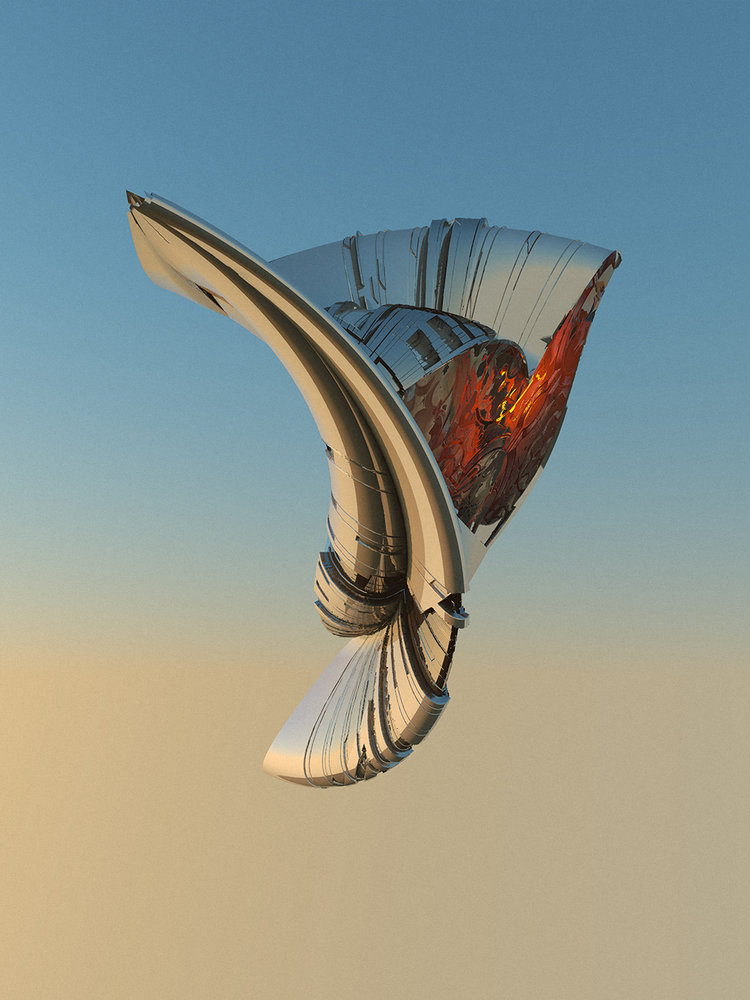

SpaceMosque, Saks Afridi’s exhibition at Aikon Gallery, New York City in 2019, elaborated a myth of a spiritually conscious spaceship that visited earth to answer prayers through fabricated evidence. The artist dispersed photographs of “sighted” UFOs that resembled a minaret crossed with a drill bit among artefacts such as a “prayer catcher”, a prayer rug turned transmitter that beams signals from the “du’a network”. Since moving from Peshawar to New York, Afridi has used “Islamofuturism” to explore the condition of living as a diasporic Muslim. I am drawn to his work as it evokes my own experience of living between simultaneous realities as a brown Muslim in Britain.

I write this essay both in the Islamic lunar month of Dhu al-Qa’dah and the Gregorian solar month of June, in the year 2020 after the birth of Christ and the year 1441 after Hijrah. I woke up at seven thirty this morning and will sleep at ten thirty this evening, yet the span of my day also runs from dusk to dusk, starting with the Maghrib prayer yesterday and ending with the Maghrib prayer today. I used to spend my weekdays at a secular school and weekends at a madrassah, learning to read Arabic in one direction and Latin script in the opposite, acquiring the muscle memory to open the Qur’an from one side and my schoolbooks from the other.

- Saks Afridi, Sighting 4; Sighting 3; Sighting 6. All from the SpaceMosque series, 2018. Courtesy the artist

Perhaps diasporic Muslims have never been in such a science fictional mood as this Ramadan, spent during the Covid-19 pandemic. In her mail-out for the ICA Daily, Zarina Muhammad of The White Pube wrote on Eid al-Fitr, “I’ve just spent the last month fasting, FaceTiming my Dad for Iftar and eating breakfast against the backdrop of islam tv in the dark silence of my kitchen @ 3am. I don’t think I’ve ever been as reliant on my faith as I am now, when everything’s up in the air and ‘after lockdown?’ is a new kinda soft future-tense speculative that means the same thing as ‘inshallah’.”

Things aligned when the pandemic and lockdown, which many described as “apocalyptic’ or “dystopian”, invoking speculative narratives, coincided with an Islamofuturist tendency that Muhammad sees as inherent in the Qur’anic command to add the disclaimer “God willing” to any future-gesturing statement, but that I cannot disentangle from my diasporic experiences of constantly moving between continuums, and seeing both my ancestral and host cultures from an alien perspective. Or perhaps the lockdown, a perceived cosmic cataclysm, brought out the futurisms of Ramadan. This month of radical sacrifices, including food, drink and sex, and radical commitments such as reading the Qur’an cover to cover, is a period of incubation before emerging on Eid the best possible version of ourselves. When the Prophet Muhammad—ﷺ (peace be upon him)—described it as “the best of days, […] the best of months, […] the best of nights”, he reached for hyperbole and superlatives as if to say that only the imagination can conceive of the restorative powers of Ramadan.

“Perhaps diasporic Muslims have never been in such a science fictional mood as this Ramadan, spent during the Covid-19 pandemic”

Although this was by no means an ordinary Ramadan, spent in isolation while mosques were shuttered and communities dispersed, I found resonances between life during Ramadan and life under lockdown. Lockdown made us lose hold of a normative sense of time, and urged us to find new temporal coordinates, such as Thursday claps for the NHS to mark the passage of another week, beautifully coincident with Shab-e-Jumu’ah or Friday evening, when Muslims usher in our auspicious day. With an entirely natural overlap, I would applaud health workers with neighbours at dusk, before returning indoors to recite du’a, reflecting on the week since the previous Jumu’ah, praying for the forthcoming week, and remembering lost loved ones. Where Ramadan depends on moon sightings and the solar transition from dawn to dusk, the temporality of lockdown aligned with natural phases rather than working hours, from the budding of plants to seasonal transitions.

Food was a fixation, as people depended on cooking and eating to structure their days, much as iftar at dusk and suhoor at dawn punctuate our nocturnal existence in Ramadan. As well this temporal disruption, Ramadan and lockdown both rewired our sensorium. Conventionally Ramadan is a time of sensory displacement, when we abstain from food and drink, and sustain ourselves through devotion and supplication instead. The oral pleasures of eating and drinking are replaced by those of reciting dhikr, du’a and Qur’an out loud. Invoking a common theoretical connection between feeding and reading, such as Hélène Cixous’ notion that reading is “eating on the sly”, reading Qur’an nourishes the soul and its temporary vessel, the fasting body.

Muslims also develop a tactile relationship with the holy book by performing wudu or ablutions before touching it, though masculinist scholarship forbids menstruating readers from touching the Qur’an, anxious that our abject bodies may contaminate this prehensile text. Likewise, lockdown forced us to experience sensations vicariously, replacing people’s physical presences with digital versions on Zoom, forgoing the multisensory textures of them in favour of the complex sensory relationships between a subject and glitchy human avatars, mediated by a screen.

This Ramadan I also came to better understand Islamic collective care, at the same time that grassroots community action was confronting governmental negligence in Britain. Galvanised mutual aid groups and offers of neighbourly support lay ground for my local mosque to use the premise of our nightly iftar for the purposes of radical care. Any other year, we would gather around a sufra or series of plastic tablecloths laid on the floor rhizomatically, sharing food that everyone had cooked for everyone to eat. We adapted this year by recruiting volunteers to prepare and deliver food, and inviting anyone in the area to state their need for food, beyond the Muslim ummah.

When lockdown brought normality to a grinding halt, and voices such as Paul Chan were wondering, “is it worth returning to the way things were?”, advocating a more equitable future rather than waiting nervously to resume a pre-pandemic past, we were able to realise other ways of living. I was struck that Islam had already provided me with a blueprint, through the cooperative structure of the community iftar; the anti-hierarchical, horizontal layout of the sufra; the notion of an ummah or collective in which each individual is responsible for everyone else, according to my grandmother’s interpretation; the solidarity between verses in the Qur’an, which instructs the reader to see it as a whole made up of plural parts, and each phrase in light of all the other phrases rather than in atomised “shreds”; and of course the Tawhid of a God who is at the same time one thing and “all things”.

Sophia Al Maria, Between Distant Bodies (still), 2013. Courtesy the artist and The Third Line

Islamofuturists and other “ethnofuturists” have warned us to treat utopian future prospects with suspicion. Expanding on William Gibson’s notion of an already-arrived yet unevenly distributed future, Afrofuturist Kodwo Eshun has argued that capitalist co-optations of the future give those in the global North the chance to inhabit a “corporate utopia”, with “smiling faces staring brightly into a screen”, while condemning those in the global South, especially in Africa, to live in “an absolute dystopia”. The Gulf futurist artist Sophia Al Maria, who was Eshun’s student at Goldsmiths, has likewise pointed out that the Gulf’s accelerated advance into the future has come at the expense of migrant workers thrust into precarious conditions. While lockdown gave us the chance to imagine equitable, sustainable ways of living, it also uncovered how much had been conceded in the name of progress.

“As well this temporal disruption, Ramadan and lockdown both rewired our sensorium”

I was both feeling the urgency of living otherwise and wondering how Islam could structure this alternative model, yet I was constantly jolted awake to the reality of living as a brown Muslim in Britain. Throughout Ramadan I saw my face disproportionately reflected in the Coronavirus death toll, as the morgue in our mosque was inundated with lives cut short, reaching capacity soon into lockdown, urgently looking for volunteers to wash, shroud and bury bodies denied a customary congregational funeral. In its review of the impact of Covid-19 on communities of colour, Public Health England confirmed that systemic racism, including the uneven distribution of money and care, made us vulnerable to the disease.

This Eid a close relative returned home at midday in distress after someone had phoned the police to break up a congregational prayer at work. He works at a hospital, where management allowed colleagues who worked on the same ward to sit together in the canteen and multifaith room throughout the lockdown in order to encourage peer support. The charges that the jama’ah was breaking social distancing rules were clearly an excuse for Islamophobia, reminding me that we are not yet cured of these evils either. This incident reminded me of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s “prayformances”, where the artist—whose practice merges Islamofuturism with queer futurity—prays in public locations such as the San Francisco City Hall with his collaborator Minoosh Zomorodinia. Together they contest gender segregation in Islam, and claim common ground for queer Muslim bodies in public spaces in North America.

Intersectional Muslim subjectivities have been some of the collateral damage of what Eshun has observed as the global North’s headlong rush into the future, denied or distorted for the sake of modernisation. For example, feminist scholars of Islam such as Leila Ahmed have noted how nineteenth-century colonial expansion, which drove forwards a prosperous future for colonial powers, captured the language of feminism to spin colonisation as a mission to rescue Muslim women from patriarchal oppression. As ongoing, raging debates about the hijab make clear, Muslim women’s agency has particularly been traded in for colonial narratives of progress, civilisation and modernity.

My relative’s experience at work, and Bhutto’s and Zomorodinia’s prayformances, remind me that these legacies persist through civic and state-sanctioned policing when Muslims take up public space. Likewise, this Ramadan the government released a video urging Muslims to spend #RamadanAtHome, and through the BBC circulated Public Health England and WHO advice for celebrating Ramadan under lockdown, as well as news of religious authorities in Saudi Arabia and Iran advising us to cancel social events and avoid fasting if necessary. I checked, and there wasn’t the same panic on Easter or Passover, perhaps unsurprisingly given that Islam and the lives of Muslims have long been the subjects of public anxiety.

“The ways Muslims presently live with Islam invoke both conservative and emancipatory futurisms, brought out during an otherworldly pandemic”

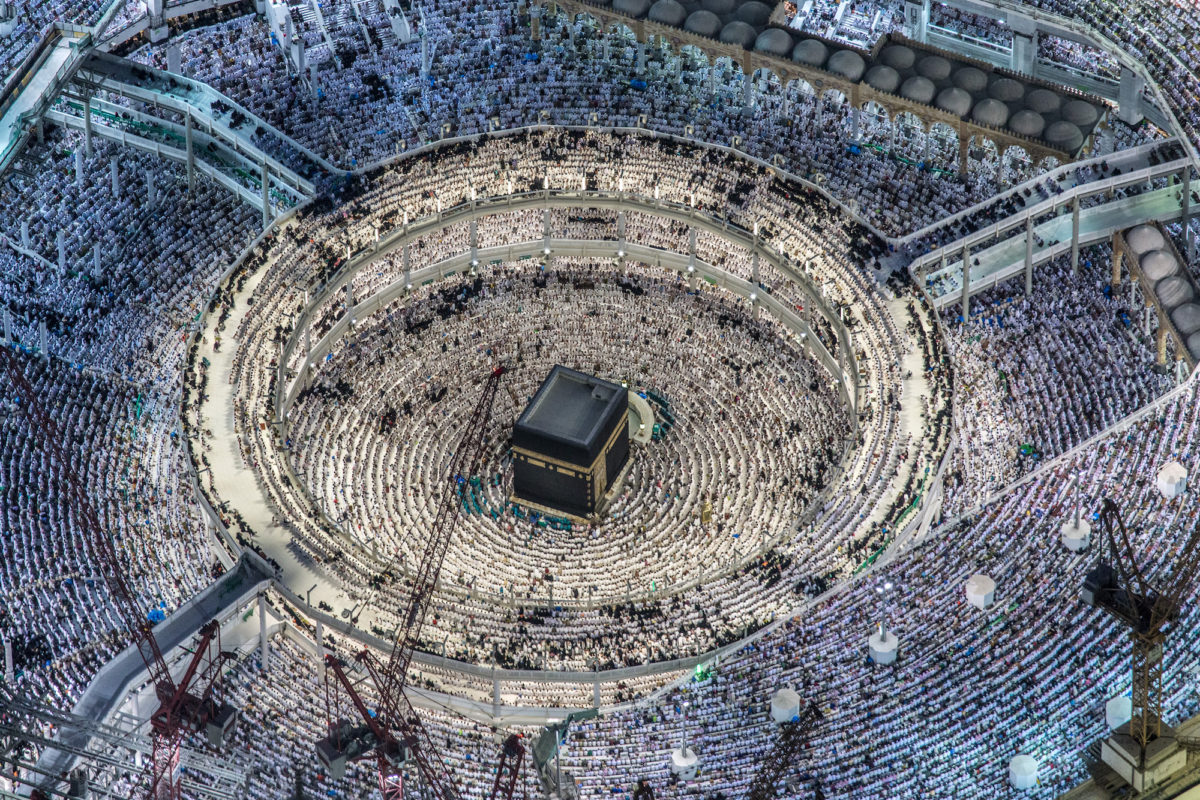

- Ahmed Mater, Desert of Pharan: Unofficial Histories Behind the Mass Expansion of Mecca, 2016. Courtesy the artist

My sense that the ways Muslims presently live with Islam invoke both conservative and emancipatory futurisms, and that these were brought out during an otherworldly pandemic, was perhaps encapsulated by Makkah under lockdown. Photographs of an empty Great Mosque resembled scenes after a planetary exodus, teasing out what has always been futurist about the holiest city. Not only has the practice of orbiting the Ka’bah had a cosmic resonance since before the birth of Prophet Muhammad—ﷺ—but the Ka’bah is also a magnet that exerts gravitational pull over two billion Muslims who pray towards it, lay the heads of their deceased facing it, and make a pilgrimage to it at least once in their lives. More recently Makkah has been an arena for the Saudi government and royal family to advance sinister futurist agendas.

Ahmed Mater’s 2016 photobook Desert of Pharan: Unofficial Histories Behind the Mass Expansion of Mecca explores Makkah’s urban redevelopment from the perspective of those left behind, including slums demolished to make way for the expansion of Masjid al-Haram, and those soon to be abandoned once future cityscapes are realised, including mostly South Asian Muslim migrant workers who endure precarious conditions for financial opportunity and to serve Bait Allah, the House of God. A medical doctor by training, Mater likens his aerial views of Makkah surrounded by cranes—raising skyscrapers such as the Makkah Royal Clock Tower, which offers the luxury experience of praying at the top of the third-tallest building in the world overlooking the Ka’bah—to a patient in an surgical theatre being operated on to death. His faith in God and medicine, however, keep him hopeful for a cure, something demanded throughout this physiologically and socially devastating pandemic.

Mater sees Makkah as a “living being that needs the least intrusive treatment possible” in order to heal from violent changes to its landscape and urban fabric that have departed from Islamic tenets. Perhaps as an antidote to the social injustices brought out and exacerbated since the viral outbreak, we could also use tender rehabilitation.