Printed matter, from pamphlets and posters to magazines and newspapers, has the ability to shape the voice of a movement, particularly if its community is not accepted by the mainstream. In the pre-internet age, to print was to prove you existed—the ephemera would last long after your death. Both printers and small presses have played a role in amplifying the message of subcultures. While the function of a printing press and publishing imprint may differ, when it comes to small or independent organisations, as with any DIY or guerrilla initiative, the two often overlap. Over the years, printing presses have not only helped educate the masses or galvanise solidarity for a cause, but offer individuals a way to make their mark on the world.

A Print Legacy

Take Howard Quinn printers in San Francisco. Up until its closure in 2012, the company was radically open in its approach to clientele—“they paid, we printed” was the phrase used by Indar Prasad, a manager at Howard Quinn since 1973. This meant that the company produced everything from the famed Black Panther Newspapers to news for sex workers via the San Francisco magazine The Spectator. This “anyone is welcome” attitude, however, meant that a single day could see them print pamphlets calling to revolt against the police, while newsletters for the San Francisco Police Officer Association rolled off the press the following morning.

It is rare for one printshop to have such an extensive impact on visual culture. Photographer Sean Dana spent much of 2012 documenting Howard Quinn’s last days. When speaking to Mission Local, a local news site for the Bay Area, Dana recalled the “tight, close relationship between presses and pressmen—they know all the idiosyncrasies… they knew the machines better than their own wives at times.” While Terry Scroggins, a former press foreman, disliked some of the more radical content that was printed, he admits “It wasn’t my place, we were just there to print it.” For Dana, the importance of preserving the relationship of a press to the information it disseminated was paramount. “I am not just photographing smudges and patina, I am preserving the physical evidence of a once proud and powerful industry… [when] deadlines ruled the day and what you put in print had a permanence only erased by a retraction.”

- The last days of Howard Quinn Printers © Sean Dana

“These smaller publications were printed via indie presses, hidden in basements or offices of political parties”

While the huge building was initially rumoured to have been bought by Google, it is now inhabited by Dandelion Chocolate. As San Francisco continues to grow around the archived site of this family-run business, the tech industry has taken the art of self-publishing to a new level, where blogs and newsletters congregate in dusty corners of the internet.

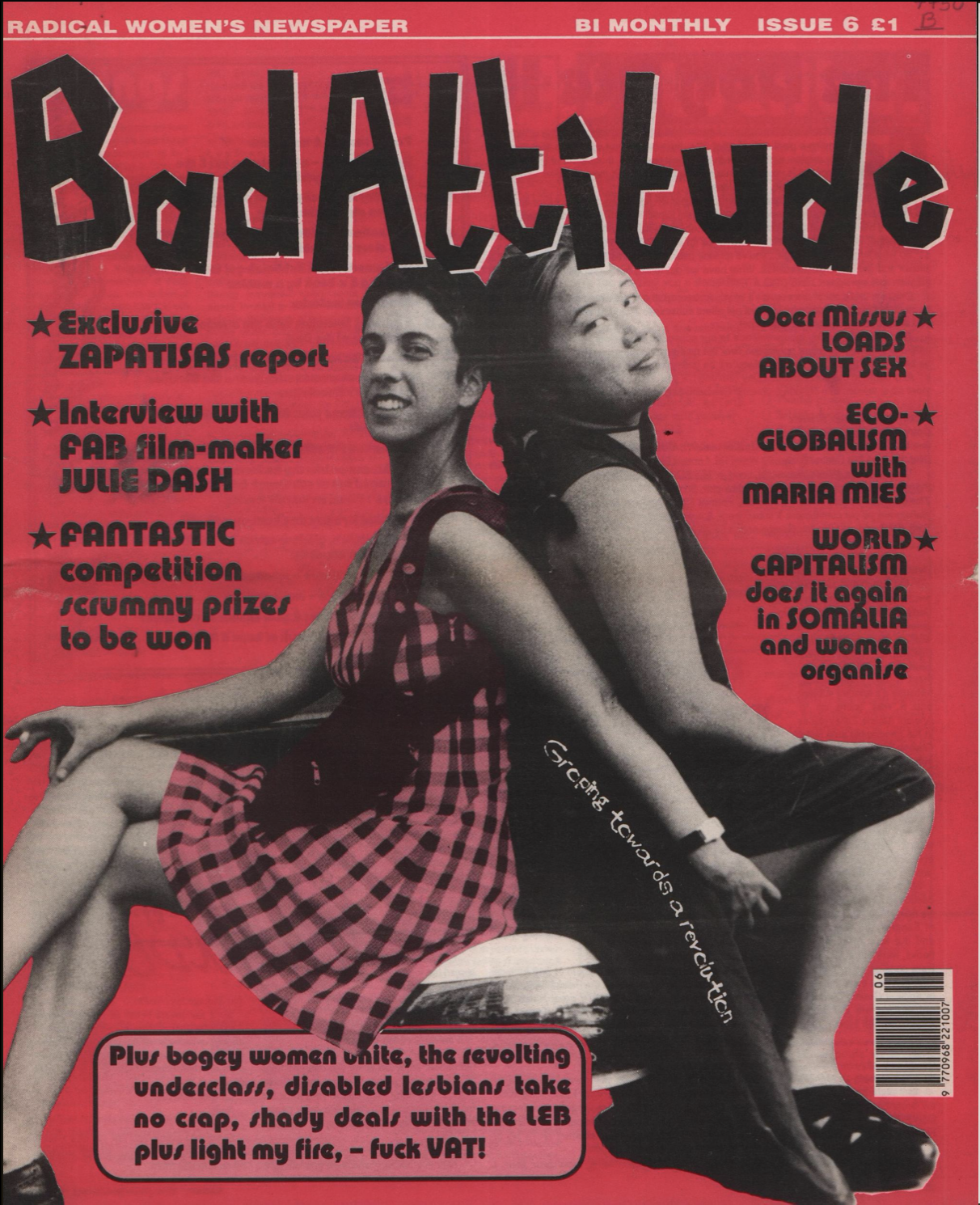

Archives like Sparrow’s Nest or Spirit of Revolt, which have taken to digitising radical printed matter, cutting through the noise. It was here that I was able to discover magazines like Bad Attitude, a radical women’s newspaper published during the mid-1990s. Bad Attitude echoes well-known feminist magazines like Spare Rib, of which the British Library has an extensive digitised archive. These smaller publications were printed via indie presses, hidden in basements or offices of political parties, with limited access to commercial printing presses.

The Subculture of Squatting

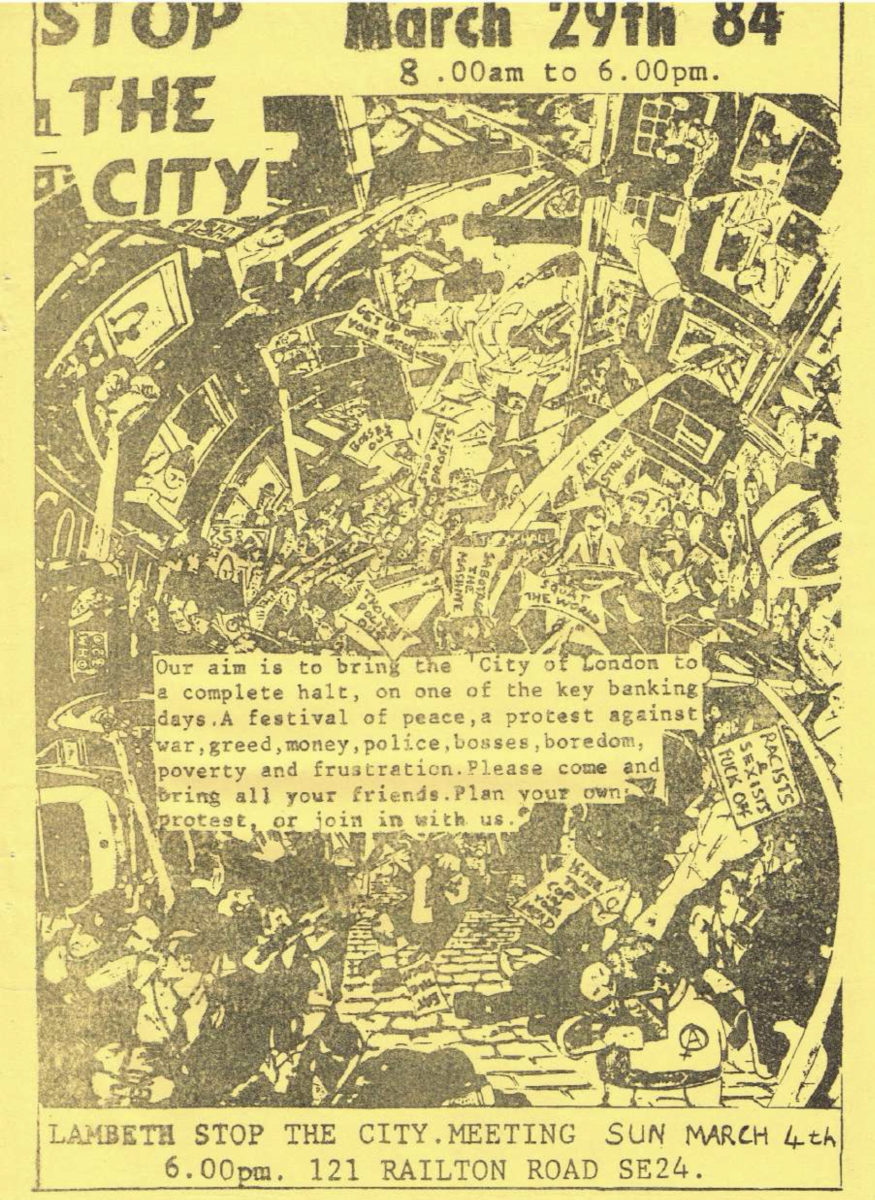

Bad Attitude is part of a wider story of burgeoning print culture between the 1970s and 1990s in London. The magazine was printed on a press in the basement of 121 Railton Road, an anarchist centre at the epicentre of Brixton’s rich cultural histories. In 1972 it was home to Black Panther Olive Morris, who squatted there with her girlfriend Liz Obi. Obi and Morris faced several illegal eviction attempts, but successfully lived there for a year before a possession order was granted to the landlord.

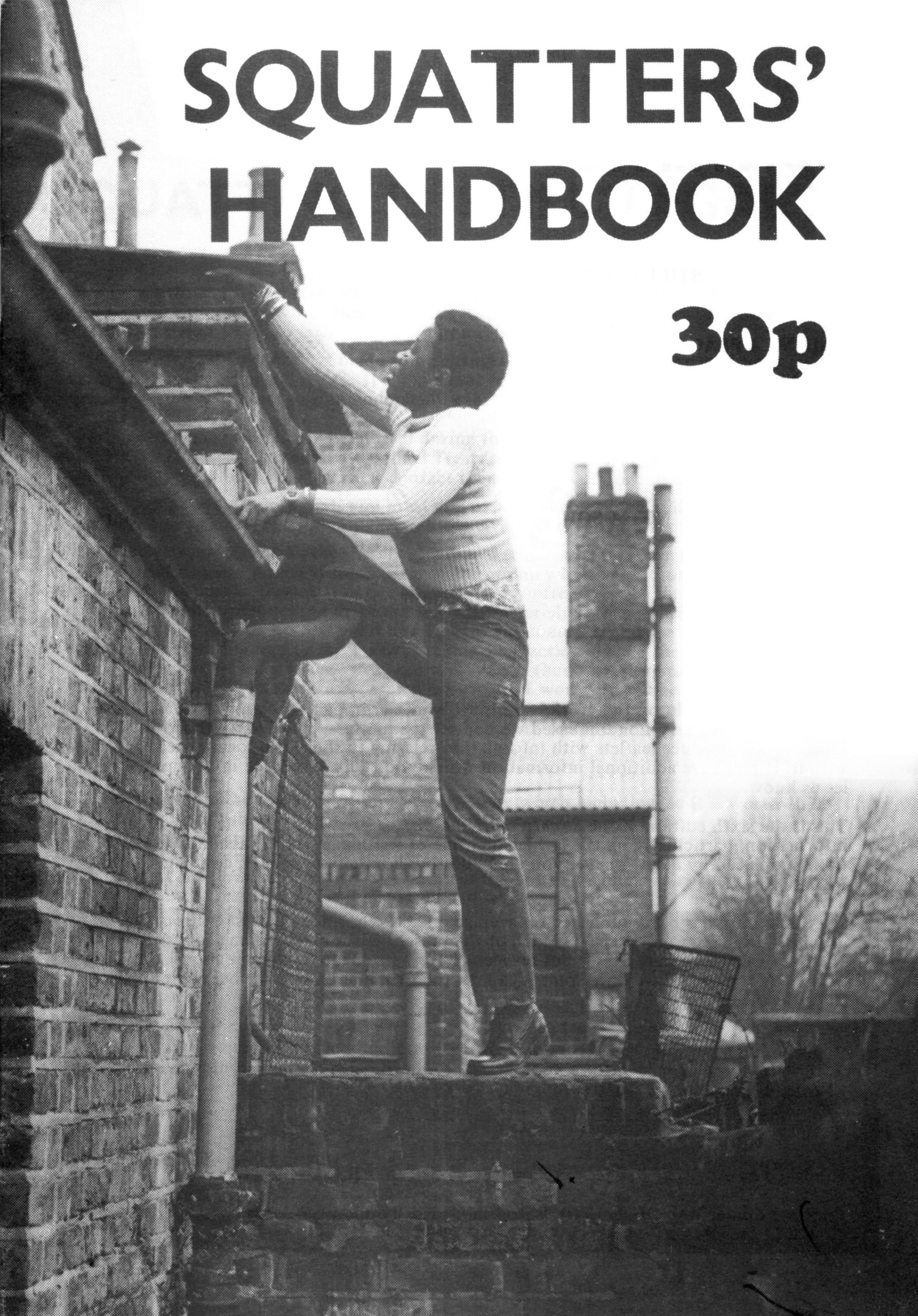

After one particularly notorious eviction in 1973, in which the police forcefully took Obi from the house to the police station, Morris simply returned from work and re-entered the house. When police officers came back to take her away, she clambered onto the roof, delivering a tirade to the street-bound policemen as she went. A photograph of Morris climbing onto the roof was published in the papers and graced the cover of the 1979 edition of the Squatters Handbook, printed by the Freedom Press in Whitechapel, East London.

View this post on Instagram

Black Radical Publishing

121 Railton Road later hosted the Sabaar Bookshop (sometimes spelled Sabarr, Sabbaar or Sarbbarr), a home for Black writers. It was used as a base for the Brixton Black Panthers, and Morris was instrumental in helping set it up as a Black advice centre. Sabarr moved to Coldharbour Lane later in the 70s—a space which eventually morphed into the Black Cultural Archives. The Black Ink Collective, an imprint for aspiring Black writers, also flourished here, producing publications such as Black Eye Perceptions. They also hosting Black Writers workshops, which were responsible for accelerating the careers of young writers such as Benjamin Zephaniah under the mentorship of first generation experts like C.L.R James.

“The two publishers were close friends and often collaborated. This sharing of resources was key to the proliferation of Black publishing in the 70s”

Black collectivity flourished at this time. New Beacon Books, the UK’s first Black publisher, was set up by John La Rose and Sarah White in 1966; while the Race Today collective, made up of Farrukh Dhondy, Darcus Howe and Linton Kwesi Johnson, published articles on anti-racist political activities. Bogle L’Ouverture, a publishing house founded by Guyanese activists Eric and Jessica Huntley in 1968, was named after Paul Bogle, who led the Jamaican Morant Bay uprising and Haitian revolutionary Toussaint L’Ouverture, and set out to transform the “status of written knowledge in the black community in Britain.”

The two publishers were close friends and often collaborated. This sharing of resources was key to the proliferation of Black publishing in the 70s—the printer John Sankey of Villiers Press serviced both Bogle L’Ouverture and New Beacon Books, as well as Allison and Busby’s, another Black publisher. Sankey’s press was well known as part of the avant-garde City Lights movement in California, for whom he had printed works by Lawrence Ferlinghetti and an early edition of Howl by Allen Ginsberg.

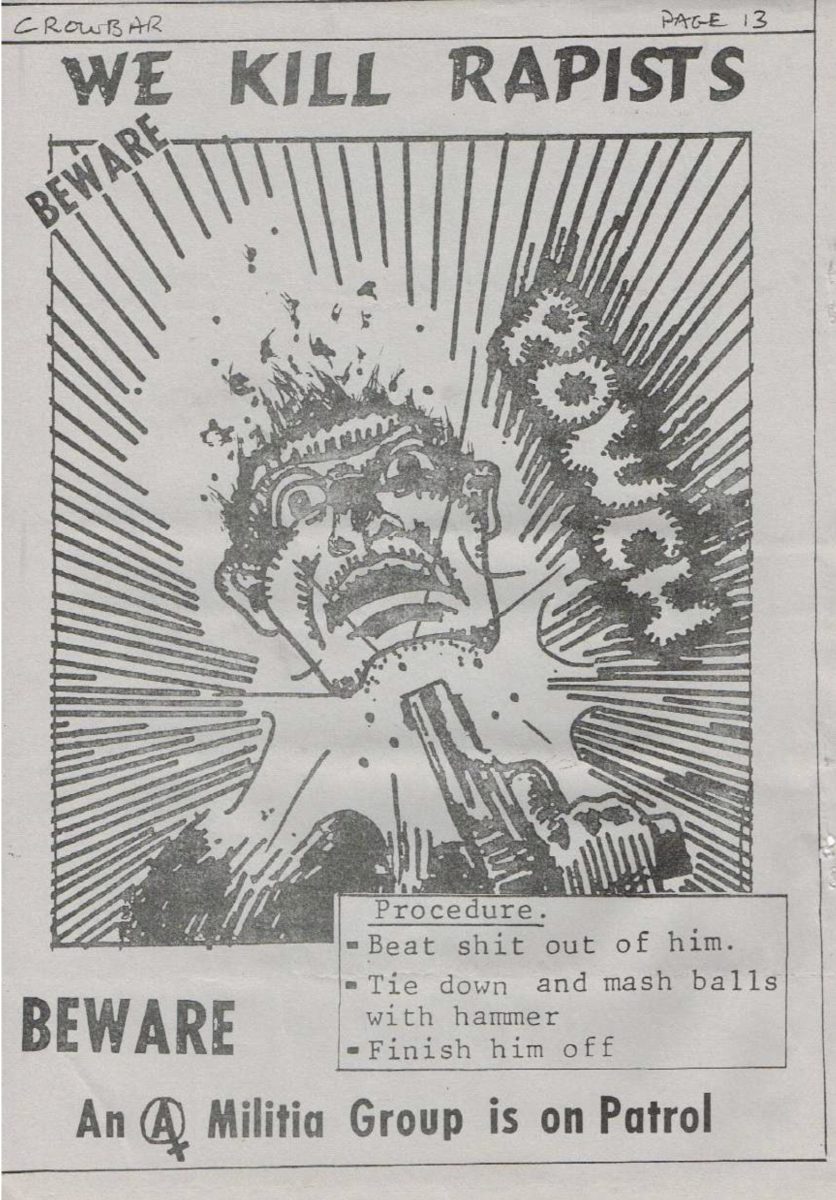

- Crowbar newspaper

Women’s Liberation Movement

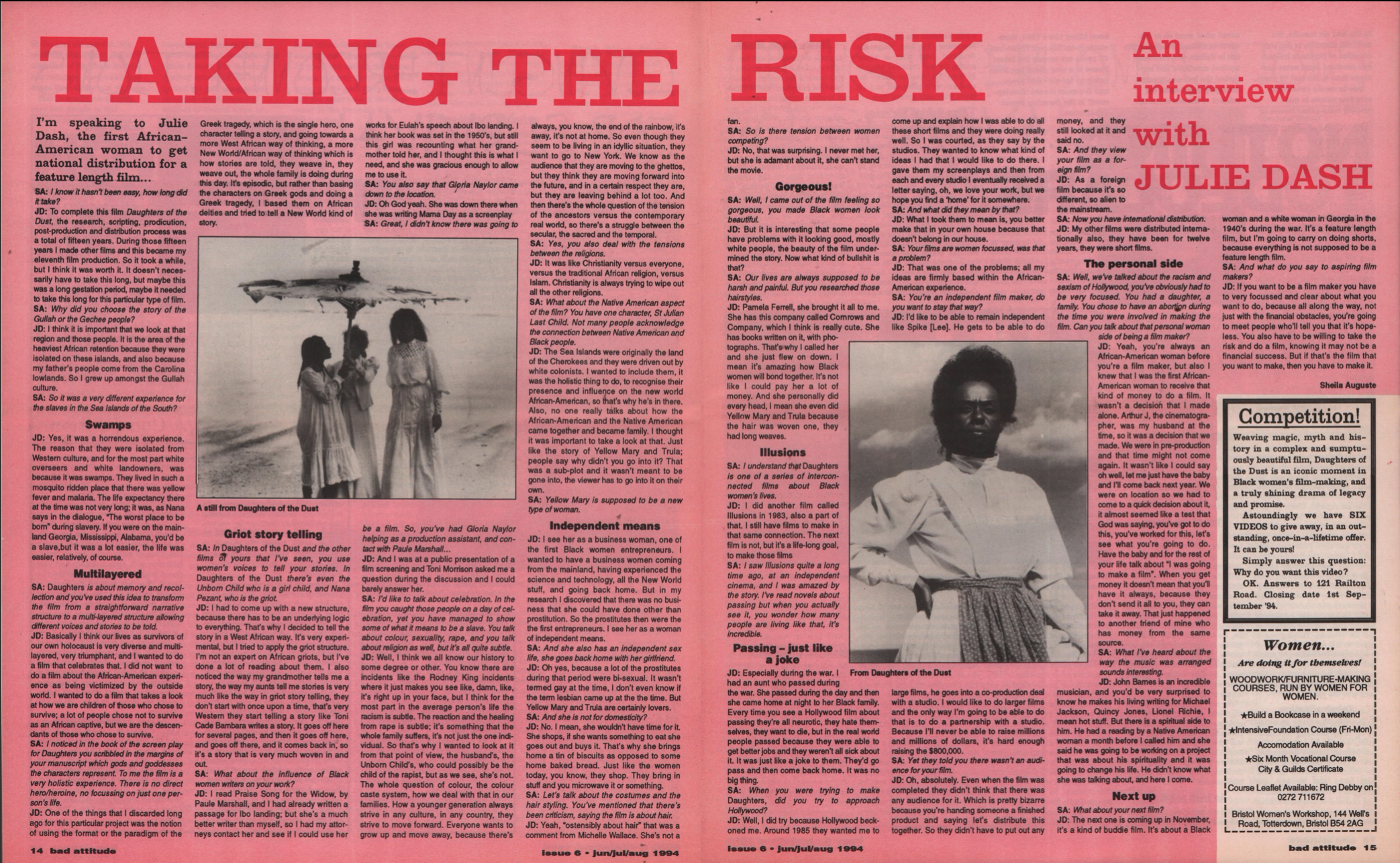

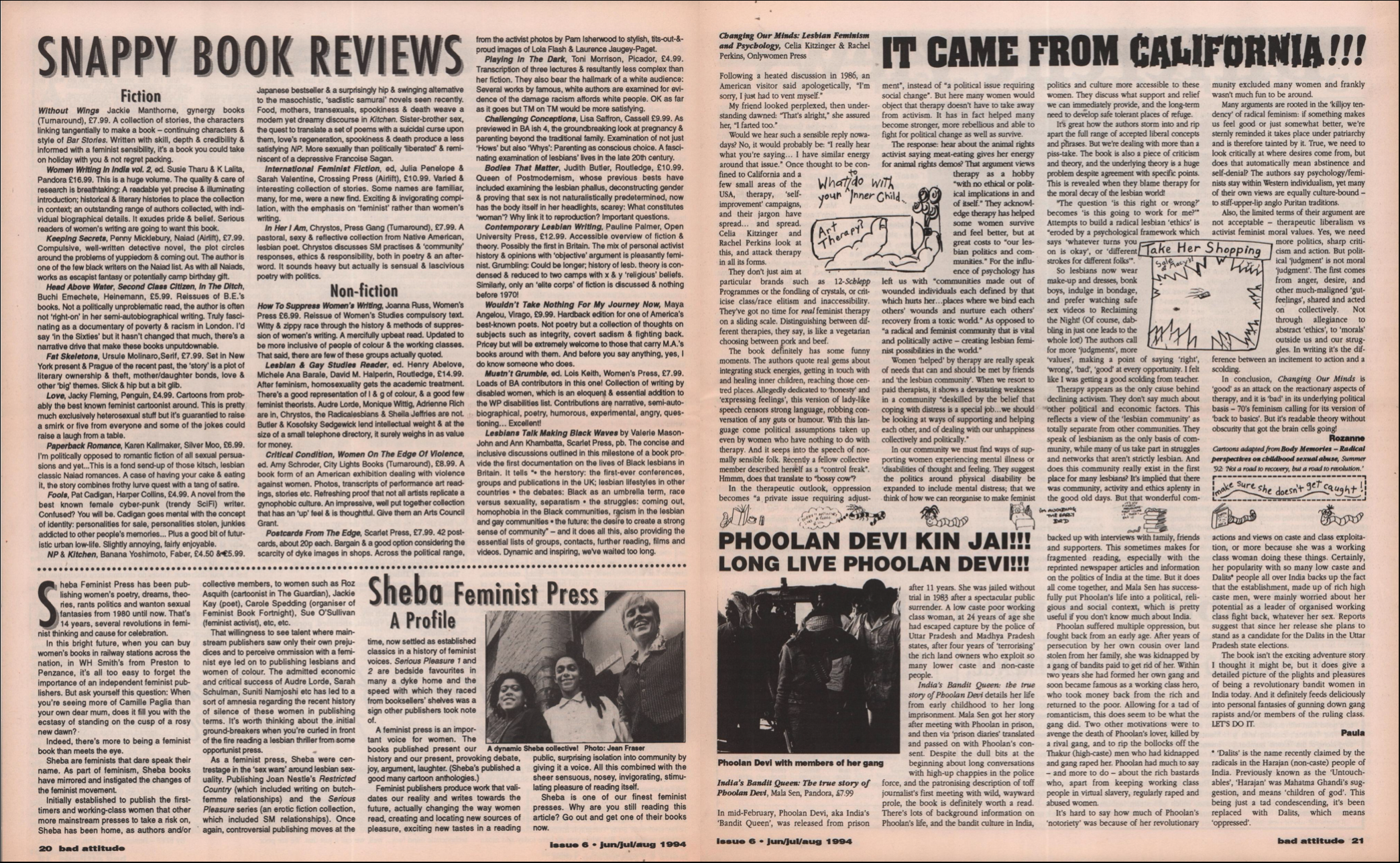

Back at 121 Railton Road, following the vacation of Sabaar books, the building became a squat and anarchist centre. It was in this incarnation of the building as the 121 Centre that Bad Attitude was printed, alongside other radical magazines like Black Flag and squatters newspaper Crowbar. In the sixth issue of Bad Attitude, nestled between an interview with filmmaker Julie Dash (an early collaborator of Arthur Jafa) and the story of Indian Bandit Queen Phoolan Devi, lies a review of one of the most underrated presses of the 80s, Sheba Feminist Press.

Little remains of Sheba on the internet. The press was a vital part of the Feminist Bookstore network, the journey of which has been charted by Kristen Hogan in her book The Feminist Bookstore Movement. Spare Rib was started to “put Women’s Liberation on newsstands” by women of the underground press, who wanted to hit back at the internalised patriarchy of commercial women’s magazines.

“Spare Rib spurred on a blossoming period of new women’s publishing houses”

This spurred on a blossoming period of new women’s publishing houses. Sheba began in 1980 to print Black and Asian women’s writing, while Virago Press was set up in 1973, alongside Onlywomen Press in 1974. Sheba were the first in the UK to publish the work of Audre Lorde, self-described as “Black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet.” One of their first publications was Feminist Fables—a retelling of myths from a lesbian-feminist viewpoint, by Suniti Namjoshi, an Indian woman.

“When lesbian-feminists were universally assumed to be white, and Indian women universally assumed to be heterosexual, Feminist Fables called into question this cosy compartmentalisation…. It can be seen in retrospect as a harbinger of the coming struggles over difference and diversity, which by the end of the decade had put paid to the myth of a unitary feminist identity,” Hogan describes. Namjoshi’s collaboration with Sheba acted as soothsayer of sorts for today’s feminism, which still grapples with the need to be intersectional while maintaining a cohesive set of values.

The Contemporary Indie Press

Today, while many imprints exist to publish the stories of underrepresented communities, (such as Dialogue Books, Merky Books, Tamarind Books) they have often been incorporated into mainstream publishing giants. While New Beacon Books and Allison and Busby still remain, newcomers like Hajar Press seek to publish the work of writers of colour on their own terms. The resurgence in independent publishing is visible also in artist-run initiatives, such as Granby Press in Liverpool or the Glaswegian Tender Hands Press.

Rabbits Road Press, a community-centred risograph press based Newham, is run by the collective One Of My Kind (or OOMK), made up of Sofia Niazi, Rose Nordin and Heiba Lamara. Risography and accessibility go hand in hand—originally manufactured in 1986, riso machines were used by schools, prisons and activist groups to mass produce posters, pamphlets and small publications. The machine’s design, which works like a photocopier paired with the bright colours of silkscreen, makes it ideal for low cost, bulk printing.

Rabbits Road Press has been running since 2016, and while the initiative offers private printing sessions in order to keep itself running, the main focus has been weekly open access sessions. Every Wednesday afternoon, the press opens its doors to the public—you can be inducted on the risograph for free and receive five complimentary prints. This ethos has drawn audiences in from across the capital, from art students to teenagers dragging their younger siblings along to amuse them for an afternoon.

“The resurgence in independent publishing is visible also in artist-run initiatives, such as Granby Press in Liverpool or the Glaswegian Tender Hands Press”

While these afternoons have been highly successful in drawing the surrounding community into the building, I asked Niazi about the challenges of running an independent space. “It’s really difficult for indie presses to survive if they need to be making a big profit, but I also think the art that needs to be made will always get made, so hopefully there will be demand, pressure and support for the sites that support artists to survive or to be reproduced.”

She continues, “We’re just trying to make a space where people can give themselves some time to reflect, connect and make art in a way that feels grounded.” Her words give me cause to think about whether it is this attitude that makes the press so successful, focusing on a smaller, more intimate scale on conversations between friends and spaces for connection. In an age of creative grandstanding, their straightforward desire to simply spend more time together may in fact have the most effective impact of all.