On 9 February 2020, a 25-year-old woman named Ingrid Escamilla Varges was brutally murdered at her home in Mexico City. After she apparently questioned him for drinking, Erik Francisco Robledo Rosas flew into a rage and stabbed his partner of five years multiple times. Ingrid’s killer then mutilated her body in an attempt to hide the evidence. He removed her skin and several organs, attempting to dispose of them in the toilet and on the side of the street in a bag.

On 9 February 2020, a 25-year-old woman named Ingrid Escamilla Varges was brutally murdered at her home in Mexico City. After she apparently questioned him for drinking, Erik Francisco Robledo Rosas flew into a rage and stabbed his partner of five years multiple times. Ingrid’s killer then mutilated her body in an attempt to hide the evidence. He removed her skin and several organs, attempting to dispose of them in the toilet and on the side of the street in a bag.

The killing was particularly brutal but perhaps not particularly surprising. Mexico has the second highest rate of female murder within Latin America: an average of 10 are committed every day. Of these, only 3% are criminally investigated and just 1% result in convictions. The murder was quite literally an everyday occurrence, but the delight of the sensationalist Mexican tabloids in this gruesome ‘news item’ provoked an angry response in Mexico and worldwide.

Images of the crime, sourced directly from the police investigation, were circulated by the press. “The Fault Lies with Cupid” read one headline, plastered above an explicit photo of the young woman’s mutilated body. This opportunistic move by the newspapers, and the complicity of the police in making it possible, sparked a wave of protests both on the streets and across social media channels.

“Users began to flood social media with images designed to make invisible the original violent photographs”

A tweet by friend of the victim @delia spurred a mass response. “Friends, I once saw a case of a femicide of a girl from the US in which the images of her body were leaked and her family and friends shared photos of beautiful things so that when they looked for her name the unfortunate photos would not appear,” she wrote. “So here’s some spam.”

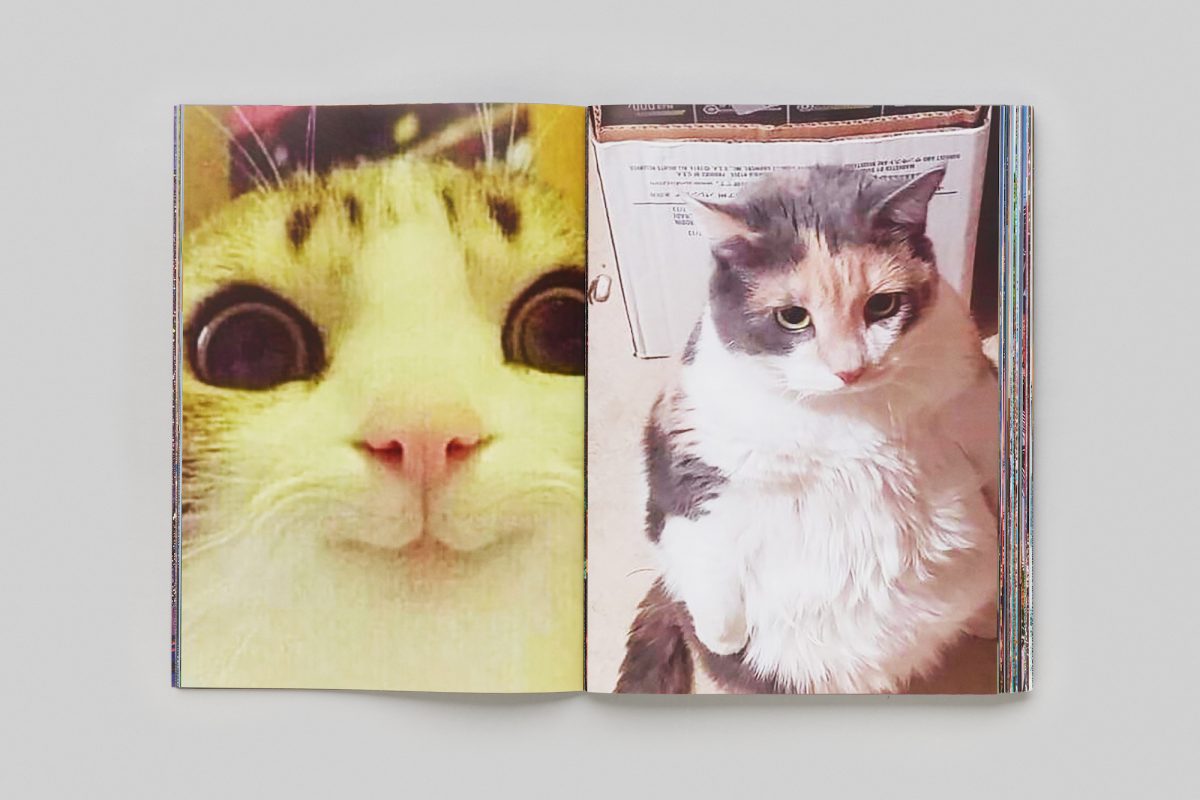

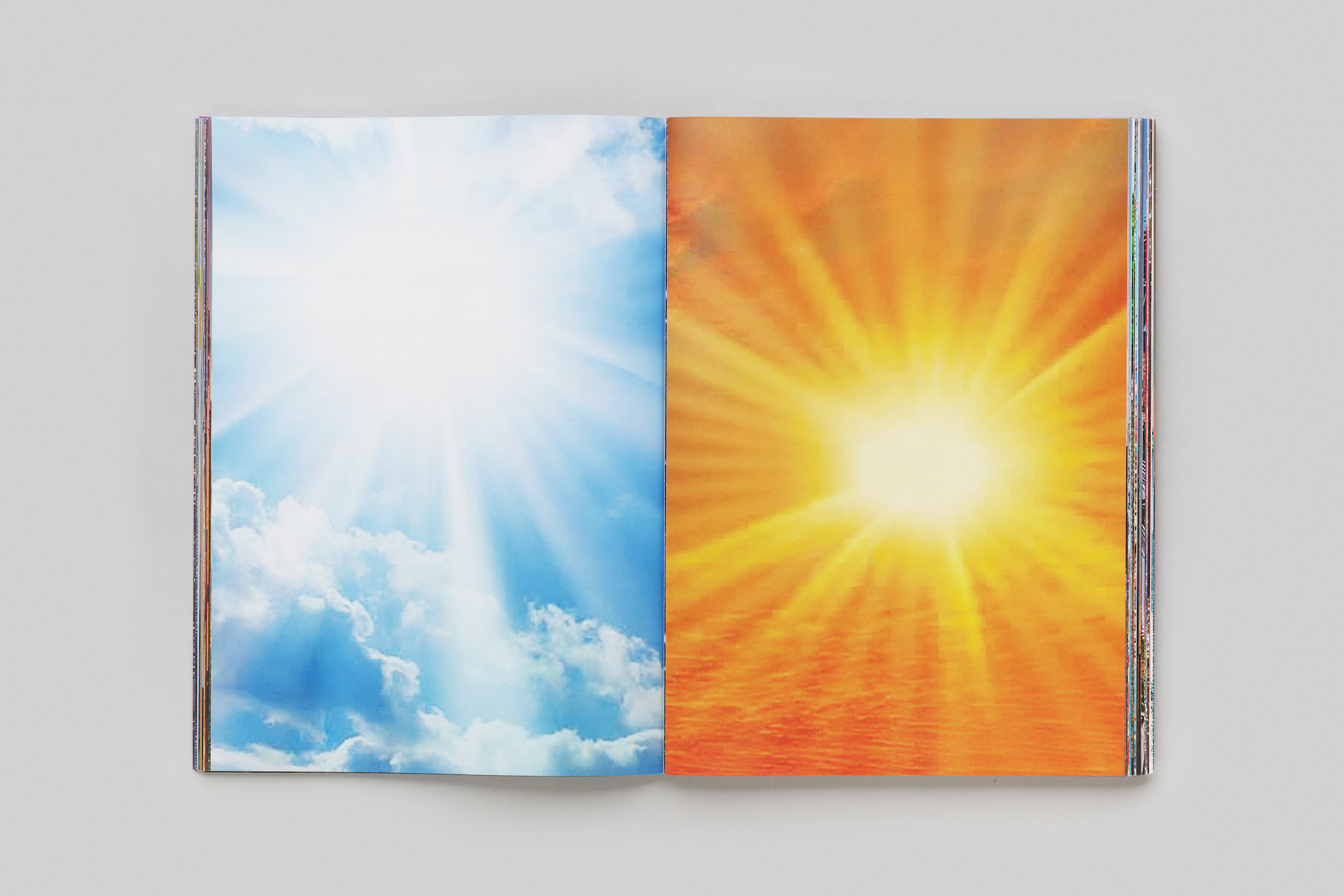

Using the hashtag #IngridEscamillaVargas, users began to flood social media with images designed to make invisible the original violent photographs. Wave upon wave of photos of natural beauty spots began to reclaim the hashtag of the victim’s name, replacing the leaked police imagery with sunsets and fields of flowers.

Swiss artist Zoé Aubry became fascinated by this participatory and popular social media movement. “This way of using images as a weapon shows the level of anger of the population of this country,” she said. “It’s a way of refuting the voyeurism that is signified by sharing those images of violence.”

Aubry has been working since 2017 on the systemic and structural phenomenon of female murder and the issues raised by the media coverage of it. For her, the way the images of the victim were circulated, both in the press and on social media, exposes structural misogyny.

“The book is important for me as a physical way to perpetuate the movement. The movement began in Mexico City but it continues all around the world”

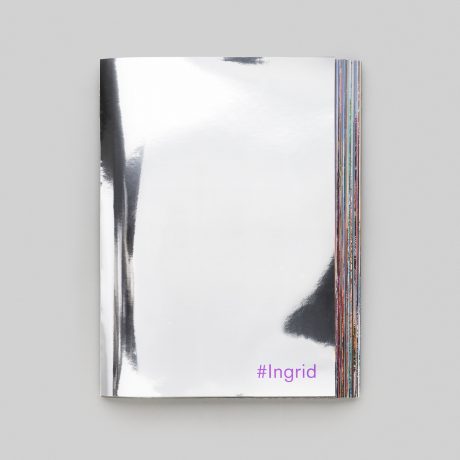

Over the course of the last two years, she has collated her new photobook #Ingrid to pay homage to the memory of Ingrid Escamilla Vargas, denounce violence against women and assail the voyeurism of a certain segment of the press. “The book is important for me as a physical way to perpetuate the movement,” Aubry says. “It can travel more widely than an exhibition and it doesn’t have the same boundaries as social media. The movement began in Mexico City but it continues all around the world.”

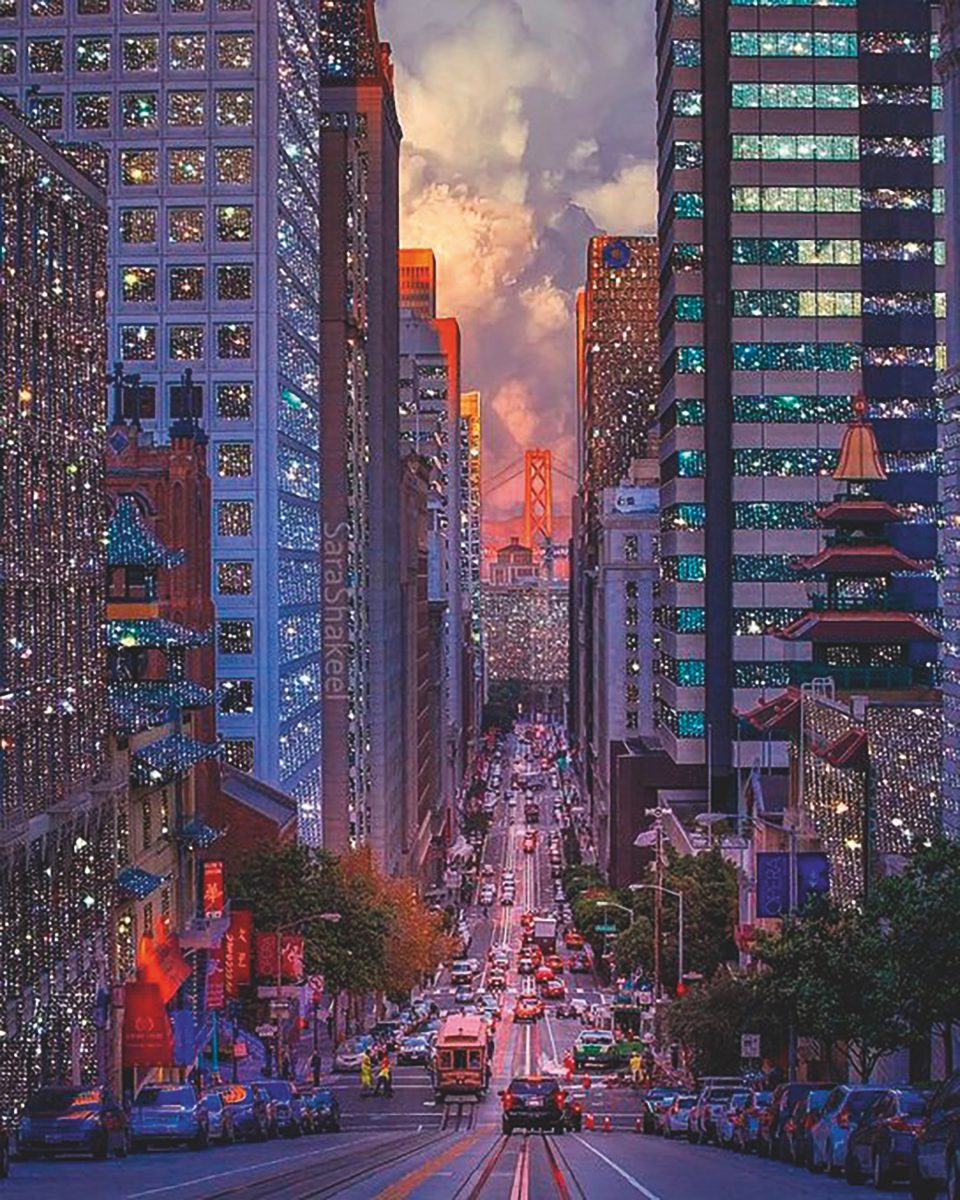

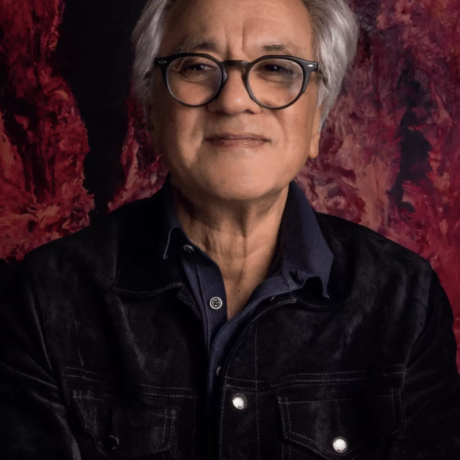

For her newly released photobook, Aubry meticulously sequences the shared social media images in date order, reflecting the way they respond to each other, working together to build an aesthetic. Brought together in hard copy, the mass of photographs makes a powerful statement. They sparkle and shimmer, celebrating natural beauty and the emotional power of the sublime.

Many are poor quality, pixelated scenes, which connects them to the grassroots quality of the protest and to its status as a form of resistance. The content of these images is less significant than their existence. Together they express the capacity of images not just to document reality but to extend our perception and express a universal depth of feeling.

The global reach of the social media movement is pertinent. The perpetuation of violence against women is not constrained by international boundaries. Femicide is a leading cause of the premature death of women globally. The case of Ingrid Escamilla Varges echoes the murder by a police officer of Sarah Everard in the UK in 2021 which sparked mass protests during lockdown, as well as the case of the two Metropolitan Police officers convicted for sharing photographs of murder victims Nicole Smallman and Bibaa Henry in 2020.

“The mass of photographs makes a powerful statement. They sparkle and shimmer, celebrating natural beauty and the emotional power of the sublime”

This commonality exposes the fact that both the killings and the media coverage follow repeated patterns and reflect attitudes that are deep rooted worldwide. In Mexico, “Ingrid’s Law” now makes it an offence punishable by imprisonment for officials to share images of crime victims.

Around the world, unacceptably high levels of violence against women continue. Aubry’s photobook exists as a permanent condemnation of violence against women and the complicity of the media in that violence.

Kate Neave is a curator, art writer and creative consultant based in London. She is the founder of Ellipsis Prints, which sells limited edition prints by women and non-binary artists

#Ingrid by Zoé Aubry is out now (RVB Books)