In 1958, the notorious gallerist Victor Musgrave exhibited a show at Gallery One space in Soho, titled Seven Indian Painters in Europe. It featured artists such as Anwar Jalal Shemza and Francis Newton Souza, who didn’t just break from tradition but reinvented it, fusing indigenous art forms with other influences such as Cubism, or Gauguin-reminiscent studies of the body. Nearly sixty years later, the Whitworth Gallery in Manchester reignited this exhibition, broadening the scope of Musgrave’s original artist lineup to include names like MF Husain and Akbar Padamsee. They gave it the title of the South Asian Modernists.

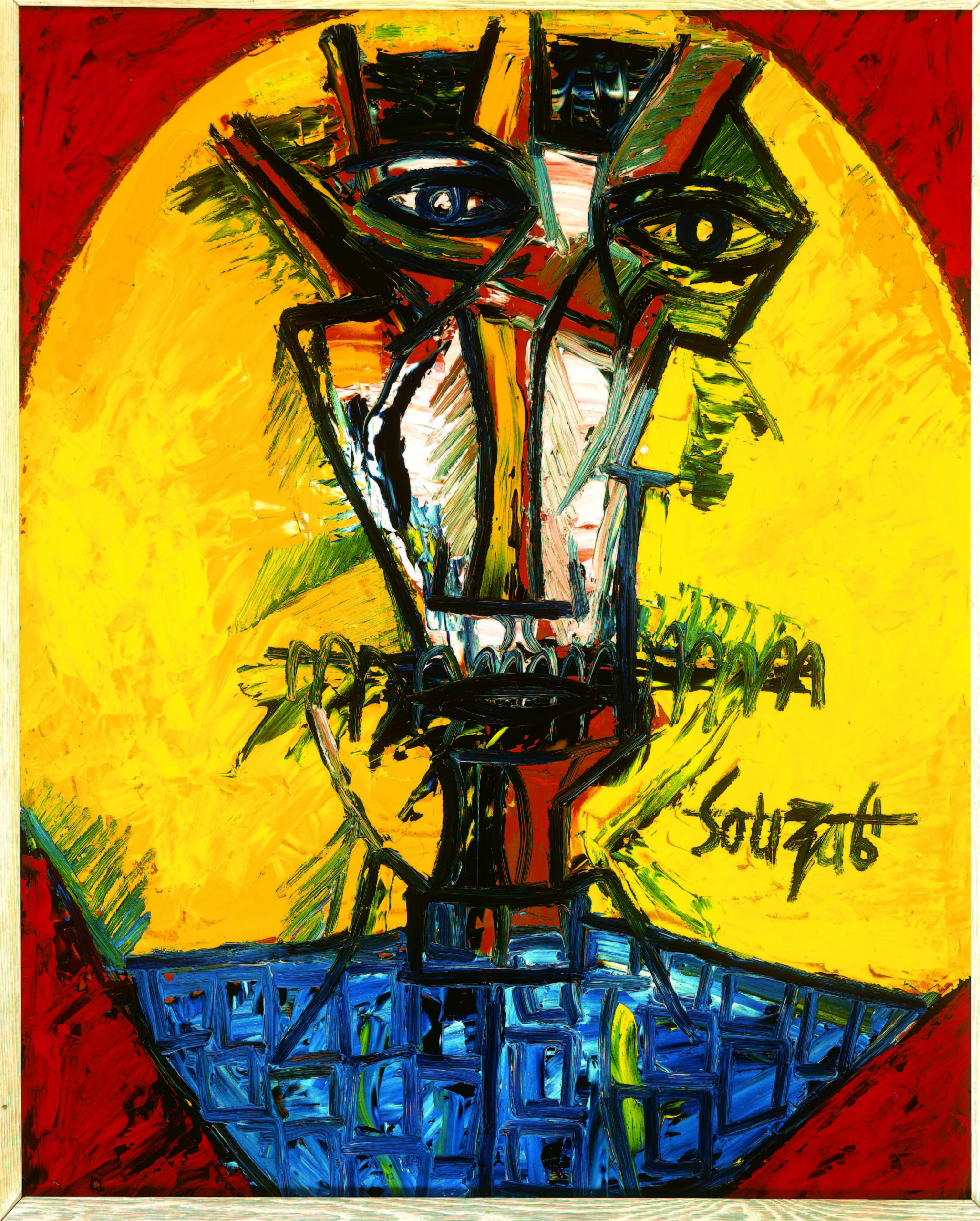

So how did this group of painters come to be? Francis Newton Souza was born in Goa, a Portuguese colony in the south of India, in 1924. A young boy whose cheeks were ridden with pockmarks, he enrolled in Bombay’s St. Francis Xavier’s High School, where he became enamoured with draughtsmanship, but was promptly expelled for drawing erotica on the school’s walls. This provocative streak continued into his brief time at Sir J.J. School of Art, where he was suspended for supporting Gandhi’s Quit India movement in 1945. The emotion he felt following his suspension was channeled into The Blue Lady, which later became one of his most famed works. In a 1955 essay, Nirvana of a Maggot, Souza wrote of his feeling of incompetence when expressing himself through words as an effect of British colonialism. Paint, on the other hand, allowed him to master his situation.

“What I’d want to do is to suspend my vocal cords on the nib of my pen… to throw my voice like a ventriloquist’s, but over a page; to emit sounds with gummed backs like postage stamps which stick firmly on paper… as I can easily do when I draw… It bewilders me to think that my inarticulation was due to England having possessed a lot of boats, which had netted India into its vast Empire. The Portuguese, too, on the other hand, had colonised Goa and had converted its inhabitants to Christianity, and this also again divided my tongue and minced my words.”

“Squeezing paint straight out of the tube, he voiced frustrations directly onto the canvas, and sculpted forms together using a palette knife“

Souza’s paintings were certainly not devoid of expression. Squeezing paint straight out of the tube, he voiced frustrations directly onto the canvas, and sculpted forms together using a palette knife. One of the most notable examples is his self portrait, purchased by collector Ruth Borchard for just 20 guineas. The painting extends his insecurities while revelling in sunny hues, both inviting the audience in, while simultaneously attempting to shut them out. The Ruth Borchard Collection describes the picture as humane and compassionate, “at once a graceful and grotesque apocalyptic vision of self”.

Maqbool Fida Husain harboured a different image of himself. Wandering around barefoot in tailored suits, he was known to brandish an extra-long paintbrush as if it were a cane. Born in Maharashtra, he migrated to Bombay to work as a “graphics wallah”, painting billboards for Bollywood films—a luscious, distinctly period visual language that is almost defunct today. Husain dabbled in film direction, to little commercial success, but still remained ardently faithful to the genre’s icons such as actress Madhuri Dixit, who manifested through hundreds of portraits as his muse.

Provocation was what brought Husain and Souza together. The former, despite making use of iconography in his work, espoused religion and politics, and in doing so, angered both. Born a Muslim, Husain often portrayed the figures of Hindu deities in the nude, or in sexual positions, earning him criticism not only in the form of lawsuits but mob attacks on his gallery. In 2006, Husain left India after hundreds of cases were filed against him for defamation of Hindu culture; he spent the rest of his days splitting his time between Qatar and the U.K.

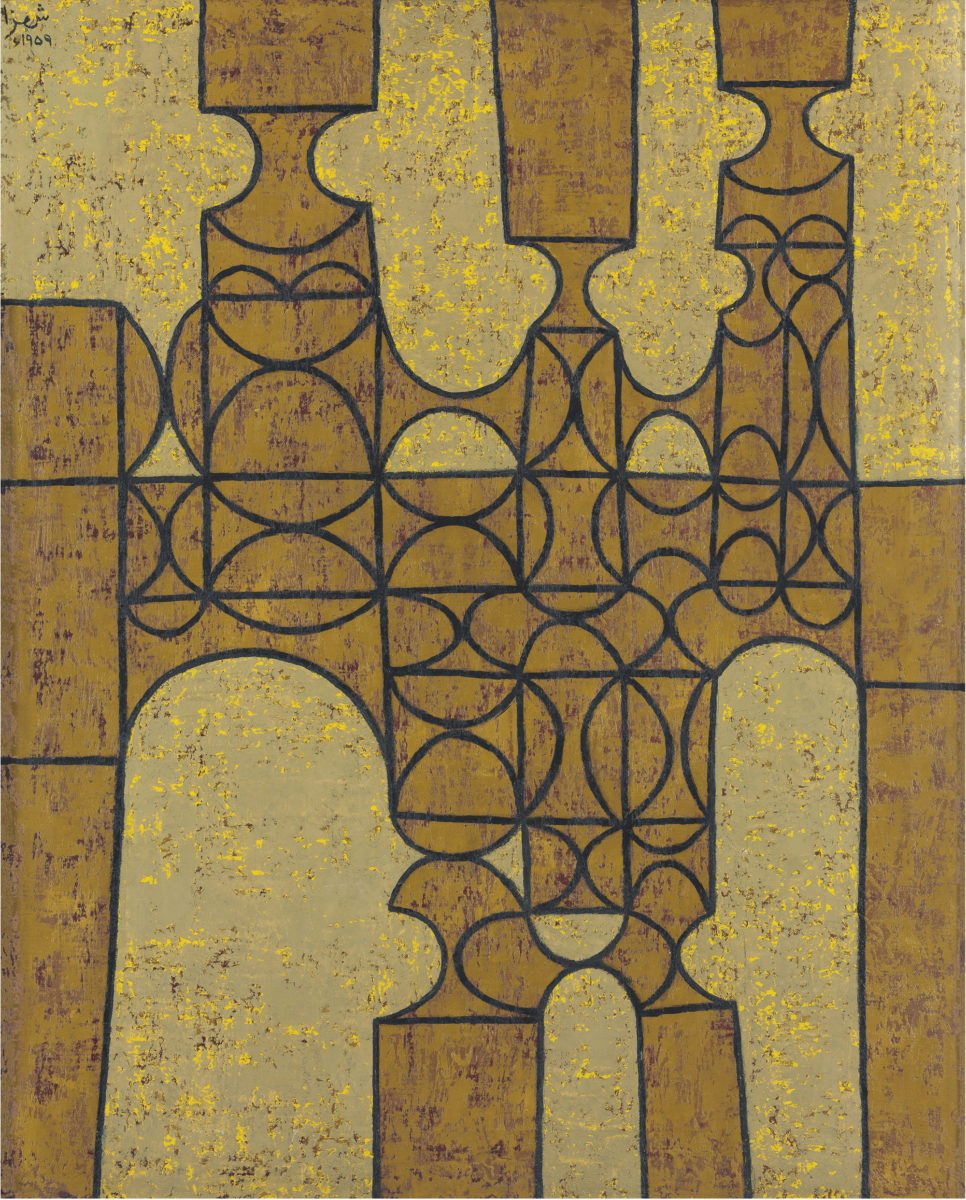

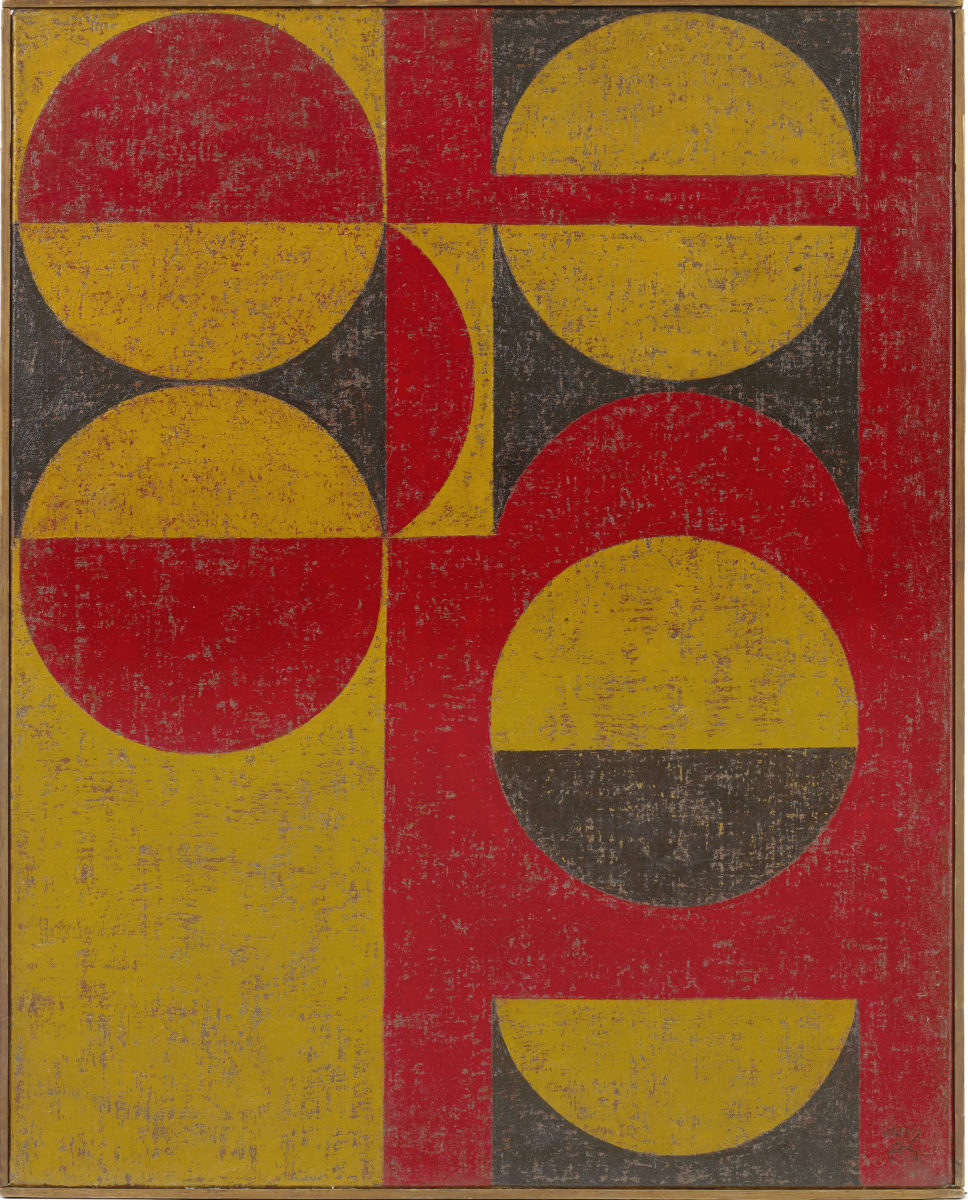

- Left: Anwar Jalal Shemza, Palace Gate. Right: Anwar Jalal Shemza, Meeting. Copyright the Estate of Anwar Jalal Shemza

In a beautiful remembrance published in Tate Etc in 2015, Aphra Shemza recalls her grandfather Anwar Jalal Shemza’s indelible influence on South Asian art. Born in the state of Kashmir, contested by both India and Pakistan, his “lyrical figurative works drew inspiration from Mughal and Hindu themes”, earning him widespread praise throughout Pakistan. After co-founding the Lahore Art Circle in 1952, Shemza moved to London to study at the Slade School of Fine Art. Similarly to the two decades Souza spent in London, Shemza struggled. An offhand dismissal of Islamic art in a lecture he attended led him to destroy his work and instead explore the abstraction of Klee, Mondrian and Kandinsky—a lesson on the consequences of a solely Eurocentric canon.

“An offhand dismissal of Islamic art in a lecture led him to destroy his work—a lesson on the consequences of a solely Eurocentric canon”

This setback, while frustrating, allowed him to embark on a different style. The Hales Gallery describes his work as exploring “modernism through the double prism of Islamic and Western aesthetics… [from] Mughal architecture from Lahore [to] the rural landscapes of Stafford, England.” Inspired by Mondrian’s dedication to grids, Shemza’s paintings were an intense study of the square and the circle, deconstructed to create a vocabulary of pattern, with resulting shapes invoking the forms of the Arabic alphabet.

Like Souza, Akbar Padamsee attended the Sir J.J. School of Art, preceding his move to Paris, where he cited influence from Fauvist painters, and was the recipient of European platitudes through a prize bestowed upon him by Andre Breton, a French critic and leader of the Surrealists. He later developed a multidisciplinary approach to art-making, flitting from bronze sculptures to photography.

Nurturing a love for nude figures, he came up against criticism when his debut solo exhibition in 1954 depicted a nude couple, the man’s hand on the woman’s breast. Georgina Maddox recalls his reaction to this situation. “They got so worked up because the work was titled Lovers. Had I called it “Mother and Child”, I wonder what they would have said then?” Padamsee was a lover of theory, and dispatched Freudian analysis when he felt that critique of his work was invalid. This was characteristic of the Modernists, who utilised intellect to battle what they saw as ignorance, while wading through controversy.

- Left: FN Souza, Green Landscape Right: MF Husain, Women in Yellow. Images courtesy Aicon Gallery

In 1947, India tasted freedom from two hundred years of British rule by celebrating its first independence day on 15 August. Now emancipated from the colonial gaze, Husain, Souza, SH Raza and KH Ara convened to take advantage of these shifting new horizons. They called themselves the Bombay Progressives Artists’ Group, forged in the crucible of a secularist, international dream, and invited many of their peers to partake in this modernist vision. Despite coming from a medley of religious backgrounds, they dreamed of a future in which art wouldn’t be held back by difference, and instead come together to celebrate unity.

Although the group was short lived, its impact was measured by these contemporaries dancing in and out of each others’ lives, across Europe and North America, to influence, collaborate and share in each others successes, notably networking their way through Musgrave’s Gallery One. Despite their progressive vision, the Partition of India and Pakistan, a condition of British decolonisation, fuelled religious tensions that still affect the countries to this day.

The term “Modernists” celebrates the Progressives’ ability to evolve the traditional South Asian art of their respective cultures while drawing inspiration from European modernism and African Cubism. This global approach to painting was a direct rebellion against the teachings of The Bengal School, which sought an Indian nationalist style as a direct rebuttal of the British Empire, which favoured styles that catered to a white gaze, both exoticising and ostracising traditional Indian subjects. The Bengal School platformed Mughal influences and Rajasthani styles that acted as a visual narration of Indian daily life, to counteract the British gaze, but the Bombay Progressives fought back against the idea of a cohesive aesthetic for the country, and were renowned for favouring global influences over a united front in the interests of nationalism.

- MF Husain, Vision XIV. Courtesy Aicon Gallery

“The Bombay Progressives fought back against the idea of a cohesive aesthetic for the country, and were renowned for favouring global influences”

Despite the commercial success that this group of artists enjoyed, there were still notable exceptions to their “boys club”. Amrita Sher-Gill, a Hungarian-Indian artist who the New York Times labelled “a pioneer of modern Indian art”, gained recognition during the 1930s. Sher-Gill almost exclusively depicted women as her subjects, and in doing so highlighted her own experiences as an Indian woman. Similarly to the Bombay Progressives, she studied in Paris at the age of 16, and fused European and South Asian cultures together to create pictures rich with despondency, which still referenced the nationalistic style of the Bengal School. The disparity between history’s treatment of Sher-Gill and her Indian Modernist counterparts didn’t end with the archive—she died at 28, allegedly due to a botched abortion. Husain and Padamsee lived into their nineties.

Alongside Sher-Gill are other trailblazing female Indian artists from the twentieth century. Arpita Singh, who was among the second generation of India’s modernists, came of age in the 1960s, a good ten years after the Bombay Progressives were founded. Known for a flamboyant use of colour and garnering of the impasto method favoured by Van Gogh, Singh’s work fits right in amongst that of Souza or Husain.

A couple of decades later, Nalini Malani’s pioneering feminist art gained widespread appreciation, reminiscent of the rebellious nature of Husain’s work. Although all these artists have seen commercial success, it’s interesting to note that neither Musgrave nor the 2017 Whitworth exhibition included female painters. While there is much to learn from the ethos of freedom that the Modernists held so dear, particularly as religious discord is sewn by India’s far-right government, remembering who was excluded is as vital as lauding the achievements of those who were acclaimed.