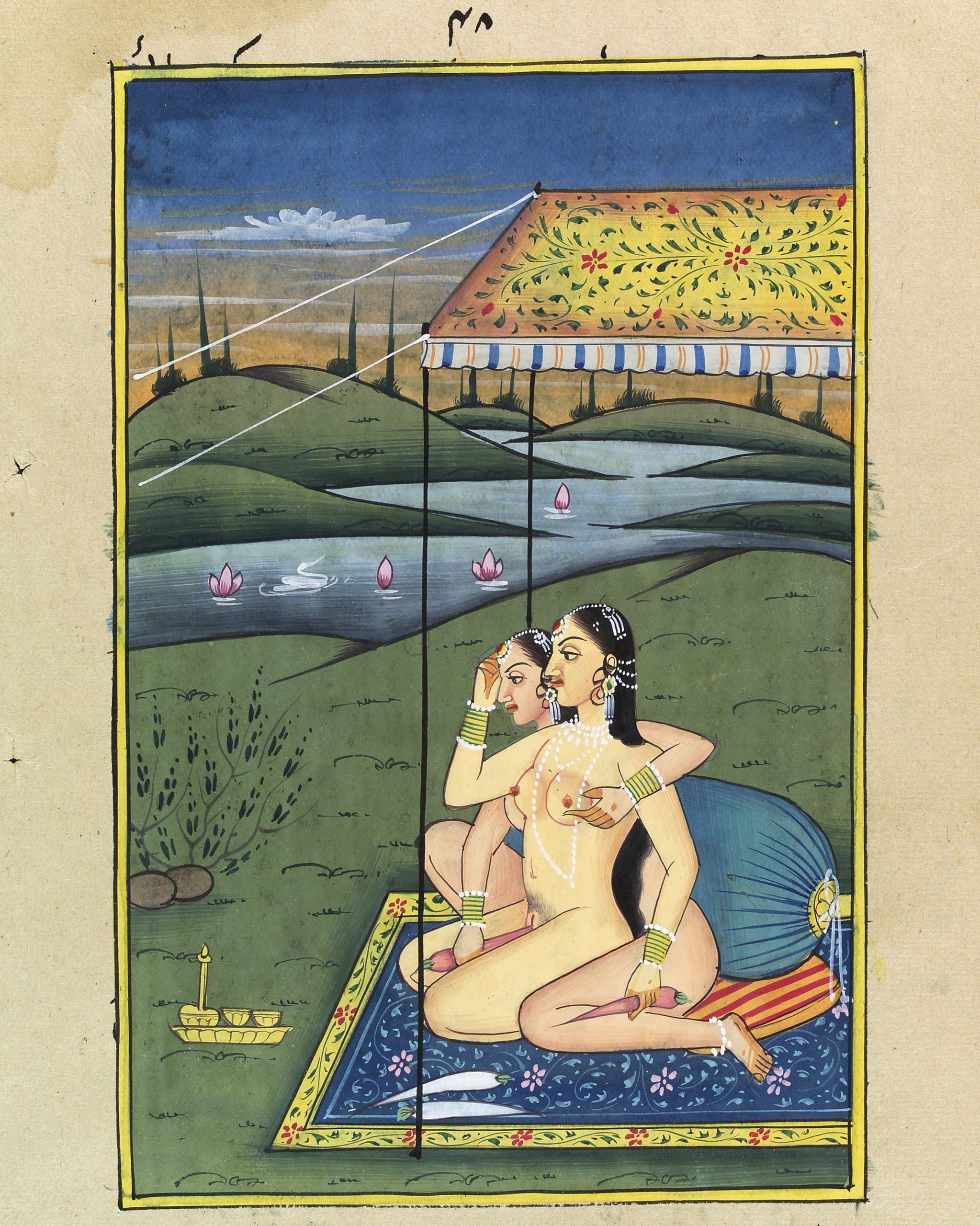

Two women embracing and using carrots as dildos. Gouache painting by an Indian painter. Dated between 1900 and 1999. Courtesy Wellcome Library

This Artwork Changed My Life is a fortnightly series of personal essays that share the stories of life-changing encounters with art.

I was brought up in an Indian family to believe that sex is shameful and so are our bodies. I was taught that women are incubators of the seed: told to fertilise and release, but not to feel pleasure ourselves. It is only the man who should feel pleasure. His pleasure equates to the release of sperm and the creation of life, whereas a woman’s pleasure is unnecessary.

It is immersed within communities, exacerbated in culture and formed in injustice. During the Mughal Empire, men were kings, men had the last word. Women had to keep themselves pure for rearing children, so were kept from stress and violence. This was a privilege of wealth, however, as those who carried children and lived in poverty weren’t allowed this liberty.

In India, patriarchal power dynamics still determine the lives of women. A 2019 Oxfam report looking at inequality in India revealed that women still earn 34% less than their male counterparts. Power and wealth come hand in hand with what governs us, so here we are, in this system of capitalism, attempting to be ‘free’, yet finding ourselves committed to antiquated standards from the days of empires.

Until my twenties, I continued to believe sexual pleasure was shameful. My mental health aligned directly with how I was perceived. If I was not beautiful, I was not worthy, and if I was not worthy of a man, then I didn’t need to exist. My body became my enemy, and I began to suffer from depression and disordered eating. I was an incredibly hairy young girl with a large hook nose and thick glasses framing my furry face. If I couldn’t align to an expectation of womanhood, then why did I even exist?

“Until my twenties, I continued to believe sexual pleasure was shameful”

Beauty is held in the eyes of brands and advertisers, who have a tendency to depict hairless, thin, white women. From razors to clothing, we are told to look perfect in order to attract a man. When I found that I couldn’t align myself to this notion of beauty, I started to wonder why I was trying. Deep down, I think that I knew I didn’t want to do anything for a man.

The shame of sex also runs deep within Indian society, and was exacerbated by British rule. Winston Churchill once famously told his Secretary of State for India that he considered us “beastly”. While previously we had practised the Kama Sutra, the British stopped us from examining our sexual needs. This included homosexuality, which is archived far back in ancient Hindu texts. With their introduction in 1861 of the Section 377 legislation, homosexual activities in India were outlawed and aligned to pedophilia and bestiality.

Queerness has no place in this journey from sexually available young girl to married woman. I have spent most of my life measuring myself by the standards defined by cis, heteronormative relationships. If I wasn’t interested in forming a partnership with a man, then would someone beyond a cis male allow me to finally exist as I truly am?

“This anonymous artwork is a reminder that I want the queer Indian community to be visible. I want to show that we’ve always existed”

I didn’t expect to find the answers in my own culture, but my discovery of a piece of gay erotica by an unknown Indian artist gave me something to examine. While scrolling through Instagram, bypassing pictures of straight white hairless women, this image popped up on my screen and I stopped in my tracks.

This piece was an important revelation in my understanding of who I am. I understood that the history of India is laden with queer love. Seeing two women pleasuring each other openly at a picnic, with a look of smugness on their faces, gave me a new confidence. It prompted me to no longer focus solely on my own body, picking at it and questioning it. Instead I began to prod at art, asking new questions. Could homosexuality be considered beautiful enough to paint?

Instead of repressing myself, I realised that I could explore my body like the women in this piece. The freedom in their posture, the certainty in their decisions, the softness in their touch all translated to how we should experience ourselves. I didn’t have to shame myself into being with a man. I realised that the shame I had felt was rooted in the heteronormative ideals that I had grown up surrounded by, where inhibitions are considered ‘decent’, and censorship of these impulses is widely accepted. I realised that sexual freedom had not always been censored.

“I didn’t expect to find the answers in my own culture, but a piece of gay erotica by an unknown Indian artist gave me something to examine”

However, the artist behind this work remains anonymous and unknown, raising further questions around censorship and visibility. The space to exist always has a limitation, and I still don’t know who the artist was that allowed me to feel that first sense of sexual curiosity. Archived in a British museum, details about it are sparse. A description reads, “Behind, a landscape with a river and lotuses”, while it is dated ‘between 1900 and 1999’. The artist remains unknown, and the Persian lettering untranslated.

Archives have the power to erase entire sections of a population. They can make lives simply disappear. World War II archives show that Indian people in the army were rarely named, especially the women. Documents weren’t kept and stories were lost. Many of us are removed from history. Finding us again is vital.

This anonymous artwork is a reminder that I want the queer Indian community to be visible. I want to show that we’ve always existed. Indian women having sexual intercourse with each other is nothing new. It’s always existed and so will we.

Sharan Dhaliwal is a writer and founder of South Asian magazine Burnt Roti. Her first book, Burning My Roti, will be released in February 2022