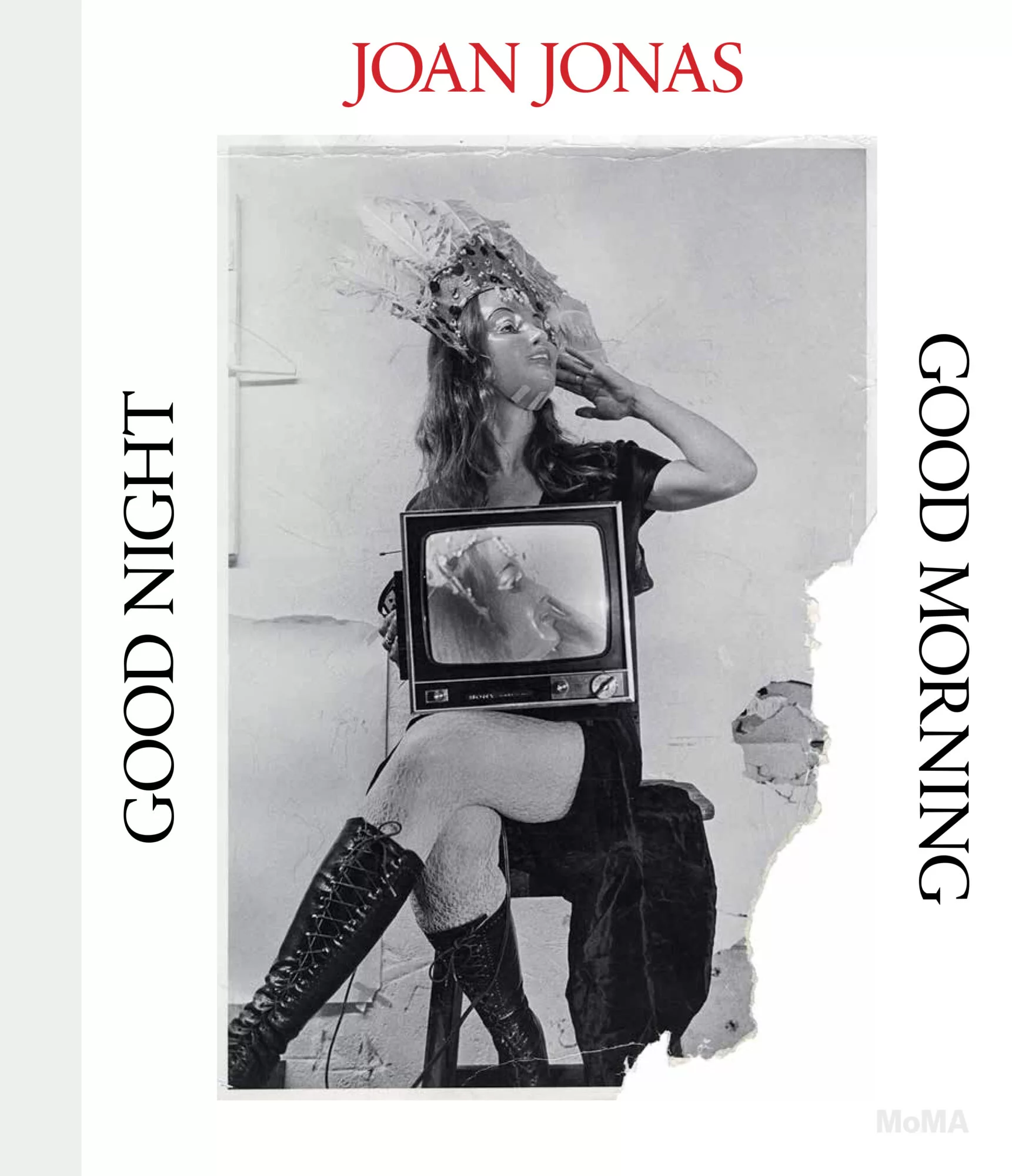

On the streets leading to the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and across the city, you’ll find posters posing a question: “Who is Joan Jonas?” On flanking posters, MoMA provides multiple answers, and varied solutions: “Joan Jonas is a Sorcerer, Joan Jonas a Shapeshifter, Joan Jonas is a Storyteller.” Working across half a decade, the New York-based artist works beyond notions of a medium, with a central focus on video and performance acting as a canvas for explorations into space, gender, bodies, land, and time.

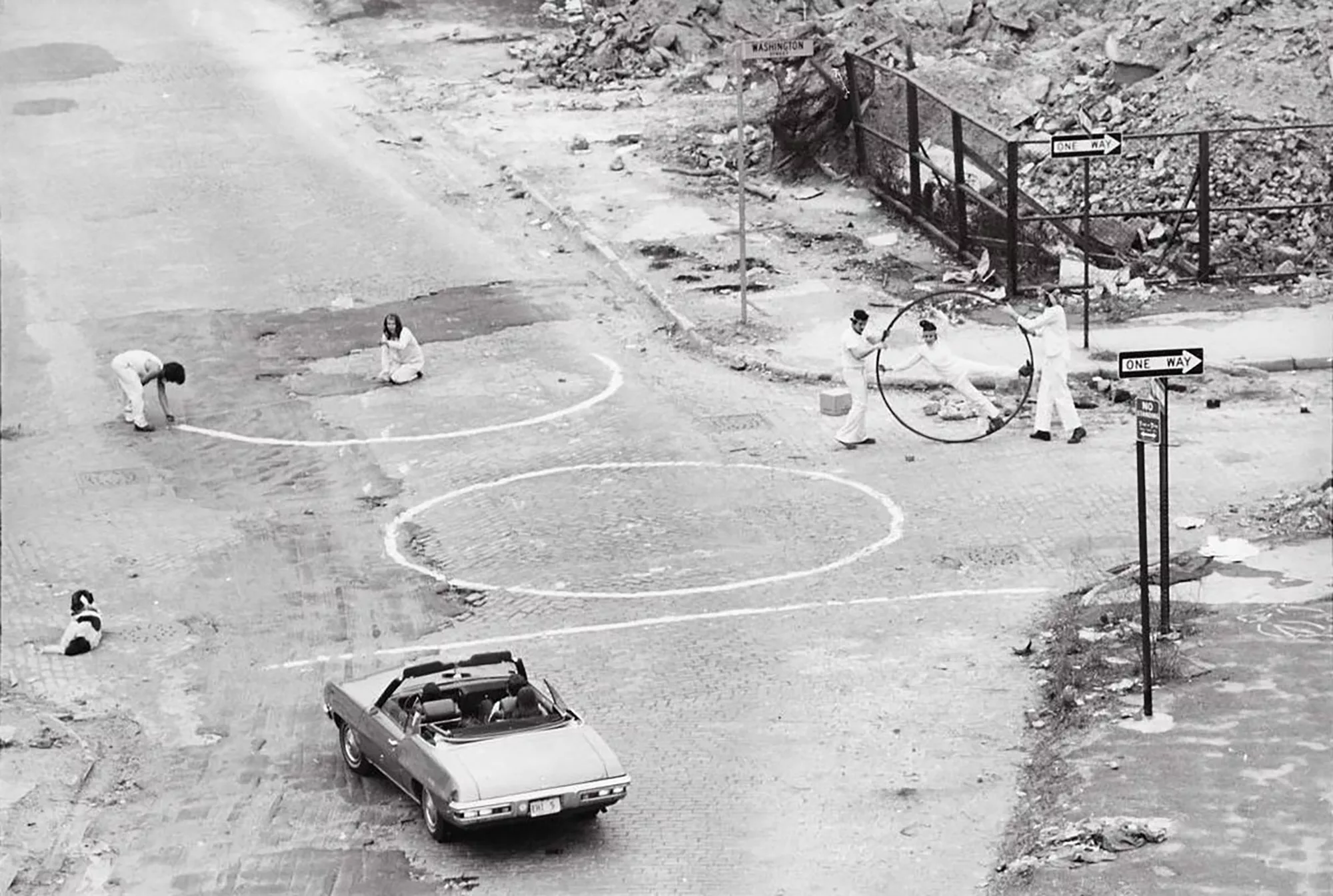

“I am always aware of the contemporary world when making a piece,” the artist explains. She describes her works as “always taking place in the present, sometimes dealing with issues of the present.” In Good Night, Good Morning, on display at MoMA March 17- July 6, a retrospective charts five decades of work, multiple presents refracting off and into each other. Jonas was an early player in the shifting, non-medium-specific world of performance art, a key player in the downtown 70’s art scene. By presenting these now seminal works in a single exhibition, alongside everything that subsequently followed, pieces cemented in art history are born once again; the first becomes the latest, and the beginning becomes the now.

For an artist concerned with time and its capacity for refraction, a retrospective provides an interesting, possibly simplistic site to play in. Running chronologically, the exhibition has the feel of a blockbuster retrospective, yet, due to the temporally transmutive nature of Jonas, the act of retrospection becomes play in itself. For Jonas and curator Ana Javenski, recontextualisation is impossible to ignore. Many of Jonas’s works feed into their successors, a lineage of tools, notions, titles and personae continuously finding new homes across her multitudinous practice. Recordings of early performances across downtown New York sit next to surviving materials: notebooks, posters, the now iconic mirror dress itself. But the pieces don’t take on the feeling of archival museum pieces; they are alive once again, literally reflecting off new contexts. Reuse and recycle, but never reduce. This dialogue across time is Jonas picked up by Jonas in a talk delivered before her 2018 Tate re-performance of Mirage – televised now in Good Night, Good Morning: “I’m playing myself, playing with myself, in 1976,” she told the audience. Sat watching the performance in 2024, the playing becomes threefold. Layers are built upon layers, with each sequential work existing on the back of everything that came before. In many ways, Good Night Good Morning is seen all at once, each element alive and together.

“Joan resists a chronology, at least, a linear one,” Javenski tells me. We’re sat at the MoMA cafe, one floor down from Jonas’s floor-wide retrospective. “The exhibition runs through a seemingly linear timeline of her works, yet, it is not as simple as a progression from one point to the next,” the curator tells me. Javenski and the team met with Jonas weekly at her loft studio, a New York centrality providing a “loop of feedback.”” It was a fantastic experience, working with an artist like that,” The curator says. “Every Thursday we would go to her loft, debate what needed to be included and how,” she says. This weekly exchange allowed for an uncovering of items never previously displayed – sketched notebooks and images from live performances taken by fellow artist Richard Serra. Archival materials from Joans’s 70’s recurring alter-ego, Organic Honey, resurface: “It was important to see the Organic Honey work included in the show as it hasn’t been seen since my show at the Stedelijk in 1994. It is one of my most important pieces,” Jonas says.

Javenski sees the works, exhibition, Jonas and her philosophy not as a straight line but as a circle, a loop feeding back into itself. “I’ve been thinking about the notion of retrospective… this idea of the retrospective looking into the past and charting a kind of progressive history. That doesn’t really apply to Joan. We tend to view this chronology in Western historical contexts, but this is something that is not true… there is no progression of one thing and then another thing after another. That’s when we started seeing instead a cyclical chronology.”

Here we see Jonas not pass the baton on, but continuously pass it back to herself, reinventing and rethinking the artistic process during the act. She turns notions of a “body of work” on its head, a “progressive history” impossible to trace with an artist always working in the present. “It is far more about trajectory and process. With Joan, you’re always between past and present.”

The show opens with mirrors, a pertinent nod to a recurring element in Jonas’s works. Jonas has employed mirrors in her performances since the early 70’s, portals allowing for refraction and redirection of gaze, form, sight and control. The “mechanics of illusion” found a repurposed home as the artist embraced technology such as film cameras, allowing performance to take on new life post-event. The camera becomes another mirror, one allowing for reflections through time. The exhibition employs this through working cameras attached to television sets, new reflections happening now in real-time. Javenski references the mirror pieces as an apt metaphor for this blurring of time and journey: “There it is in the 70’s, the 90’s. It will be there in the future too. The mirror reappears throughout the show, through her whole collection. It bounces off. She accumulates one work into another, proving that chronology might not exist. We needed to show that.”

Javenski was also aware that in a place such as MoMA, the exhibition had to make sense to die-hard fans as well as those encountering Jonas for the first time. “That’s always the challenge, to make something for everyone… paradoxically, her latest works provide a deeply accessible way into her pieces, which then feed right back to the start…once again, we have the looping, the circle.”

Sometimes with a retrospective, one gets to the end rooms and has to lug through the later works, thinking back to the greatest hits. But with Jonas, each song plays at once. The baton passes back, it passes forward. “Seeing the works all at once like this opens you to something new,” Javenski says. This pliability of time and material allowed the curator to reshape works, presenting them in ways previously unseen. Jonas’ adaptability provided a clean canvas for such rethinking. “She’s always interested in new ways, new forms,” she says. “Every time you show it, it’s completely new.”

“The performer sees herself as a medium: information passes through,” Jonas comments, the words cemented on the gallery wall. The exhibition closes with Jonas’s more contemporary “passings”, ecologically-driven works and new commissions. “It was very important for me to make a new work for the retrospective… I was happy to be commissioned by MoMA to make To Touch Sound and By a Thread in the Wind,” Jonas says. These newer works, in which Jonas encounters the “natural world as a protagonist,” see her collaborate with Japanese dancers, children, animals, marine biologists, and kite makers. She brings her open-ended approach to performance art into the natural world, the interplay between human and space finding new dialogues once again. “The works constantly evolve and reconnect: we start with some of her earliest works, Wind, and end with her newest: kites,” she says. Split by 50 years and 9 rooms, the wind blows the kites, the kites play on the wind.

Multidimensional and multidisciplinary, the “visual telepathy” of Jonas’s performances – live, recorded, ephemeral and archival, all happen at once within Good Night, Good Morning. Here it is 1976, 1982, 2001, 2018, 2024. Each lattice of her practice, each element, moment, thought and feeling, all converge — light hitting a mirror. “Video became a vehicle for women’s voices. It was unexplored territory,” the artist remarks. To be a pioneer, one of the first to venture into the world of recorded film, and now, to still be one of its biggest players 50 years on, squashes half a century into roughly nine rooms.

As one enters the exhibition, Joan’s 2006 work My New Theatre VI: Good Night Good Morning ’06 shows the artist in her Nova Scotia home, turning to the camera at the beginning and end of her day, speaking “goodnight” before she sleeps, and “good morning” as she wakes. In multiple rooms, one finds similar videos, some charting back to the 70’s. The artist skips through her own timeline, finding herself again and again. I get the sense that if the whole audience, the whole world, vanished, Jonas would remain, speaking goodnights and good mornings to herself. This retrospective is deeply introspective, an artist confident in her ability, providing heavy input and a deep knowledge of oneself.

Written by Isaac Huxtable

Joan Jonas: Good Night Good Morning is on display at MOMA, New York, March 17- July 6

find out more