It’s all well and good having, say, talent; nepotistic friends and/or family; gallery representation or a Royal Academy degree. But honestly, are you *really* an artist until you look like an artist? For those fearing their all-black outfit, scruffy tote bag and general air of irony/world-weariness just won’t cut it anymore, there’s a new guide to help you dress, accessorize and coiffure your way into the art world, taking inspiration from those who came before you.

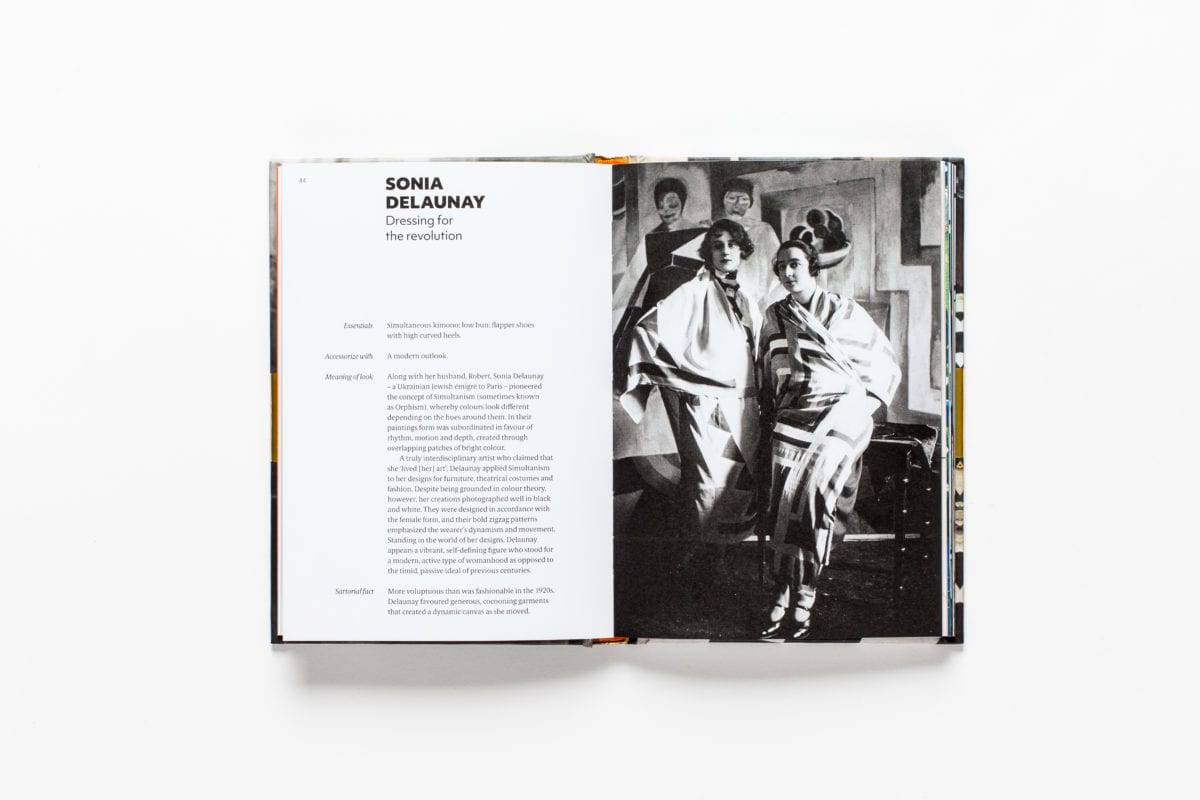

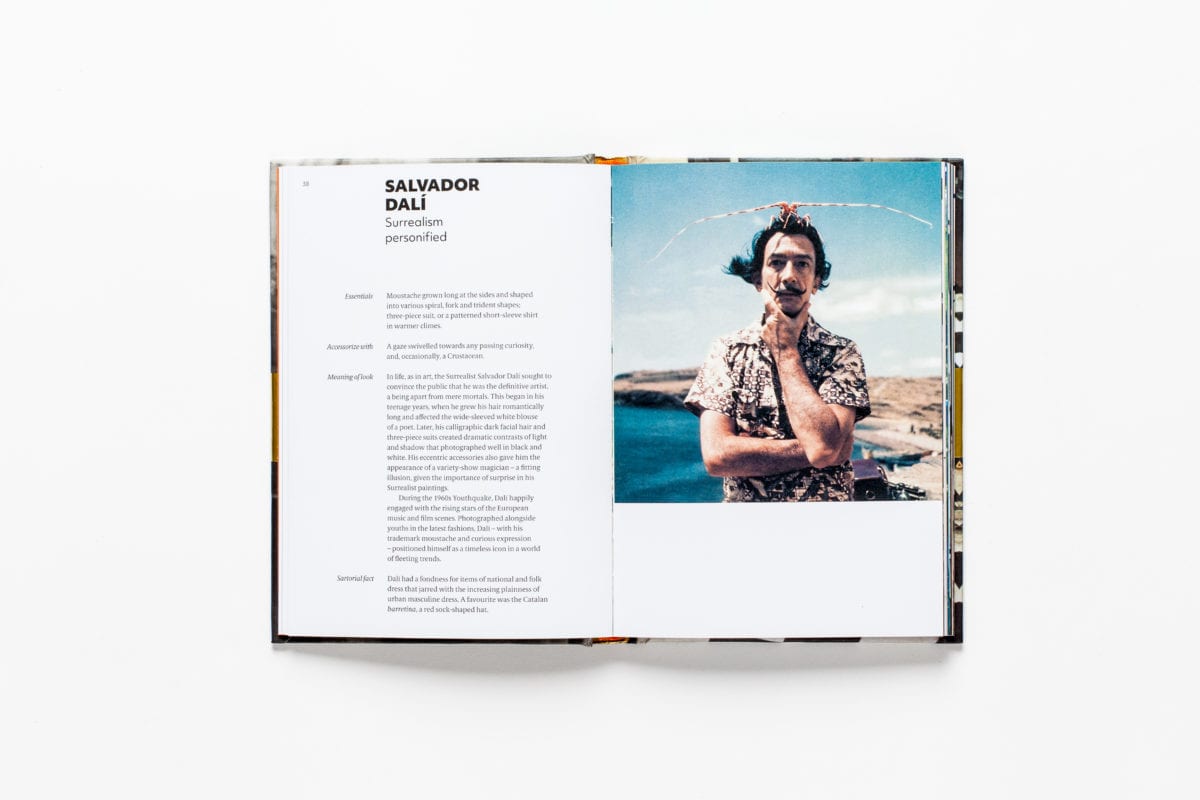

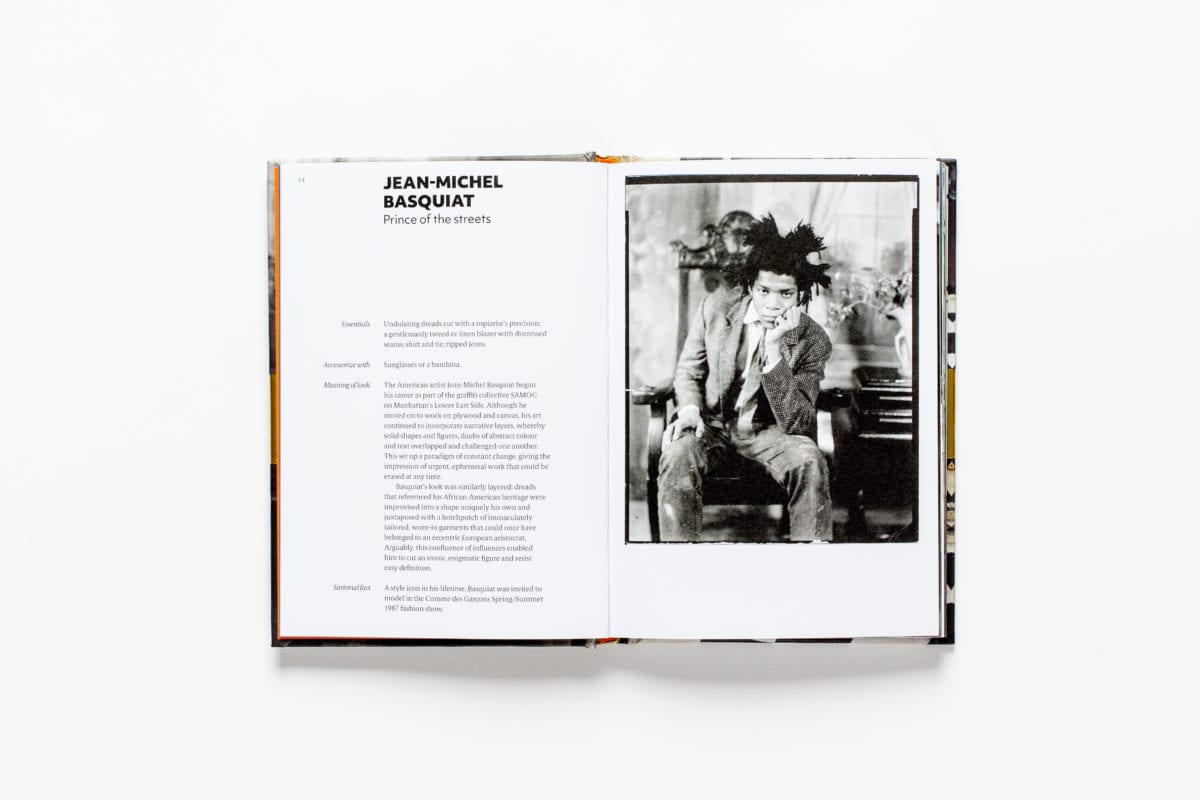

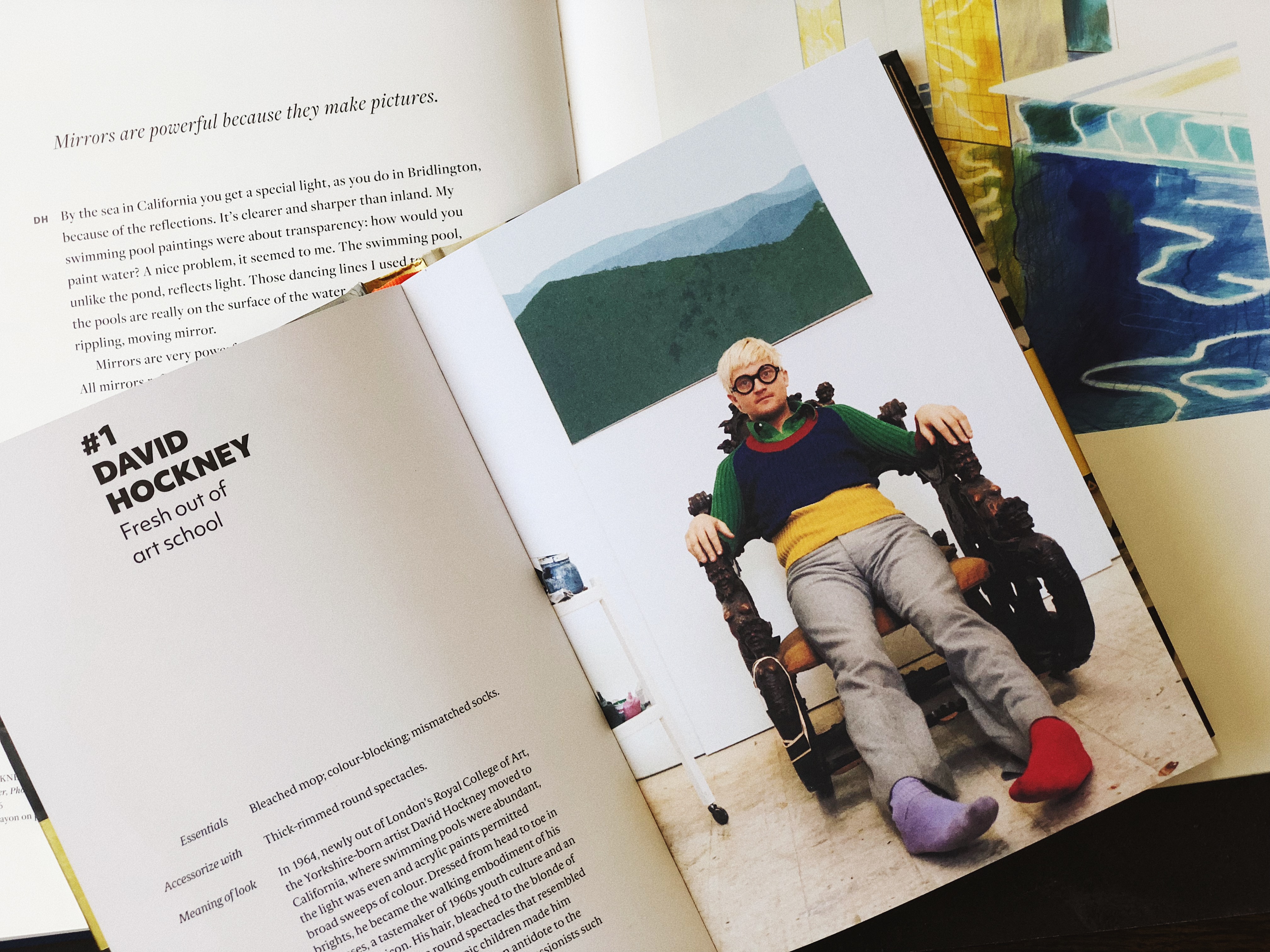

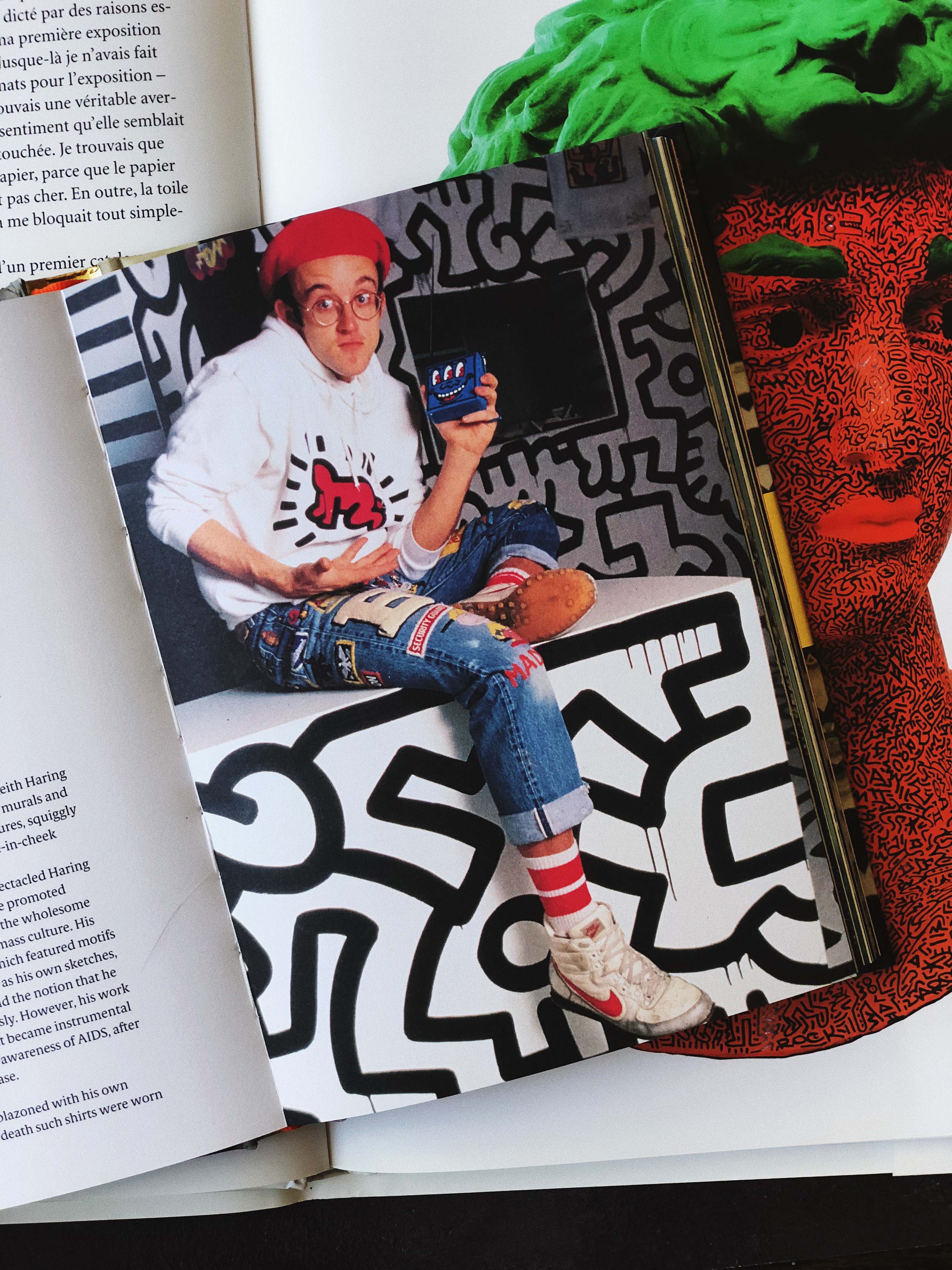

Sartorial: The Art of Looking Like an Artist is a sweet and frequently hilarious little tome by Katerina Pantelides, published by Laurence King, which showcases the “signature looks and style essentials” of sixty artists, ranging from the easily aped (Warhol’s wig, Hockney’s specs, Pollock’s precariously dangling cigarette) to the rather more tricky. To truly become Marina Abramović, the book advises, one should complete the look with a “starved python on the stomach”. You certainly won’t be finding one of those in Claire’s Accessories.

- Sculptor Cornelia Parker RA, Royal Academy of Arts' annual Summer Exhibition in London. Ukartpics / Alamy Stock Photo

- Tracey Emin, Those Who Suffer Love photocall held at the White Cube Gallery. London, England - 27 May 2009. Imagno/Getty Images

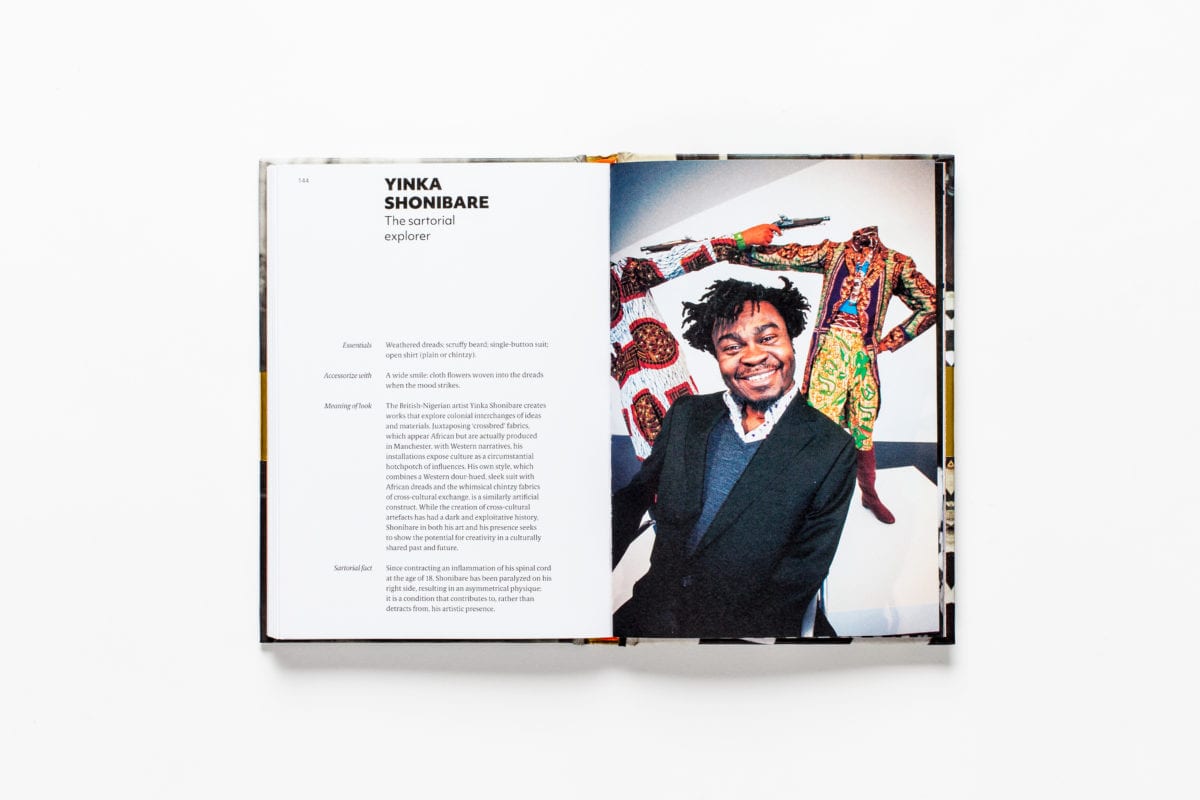

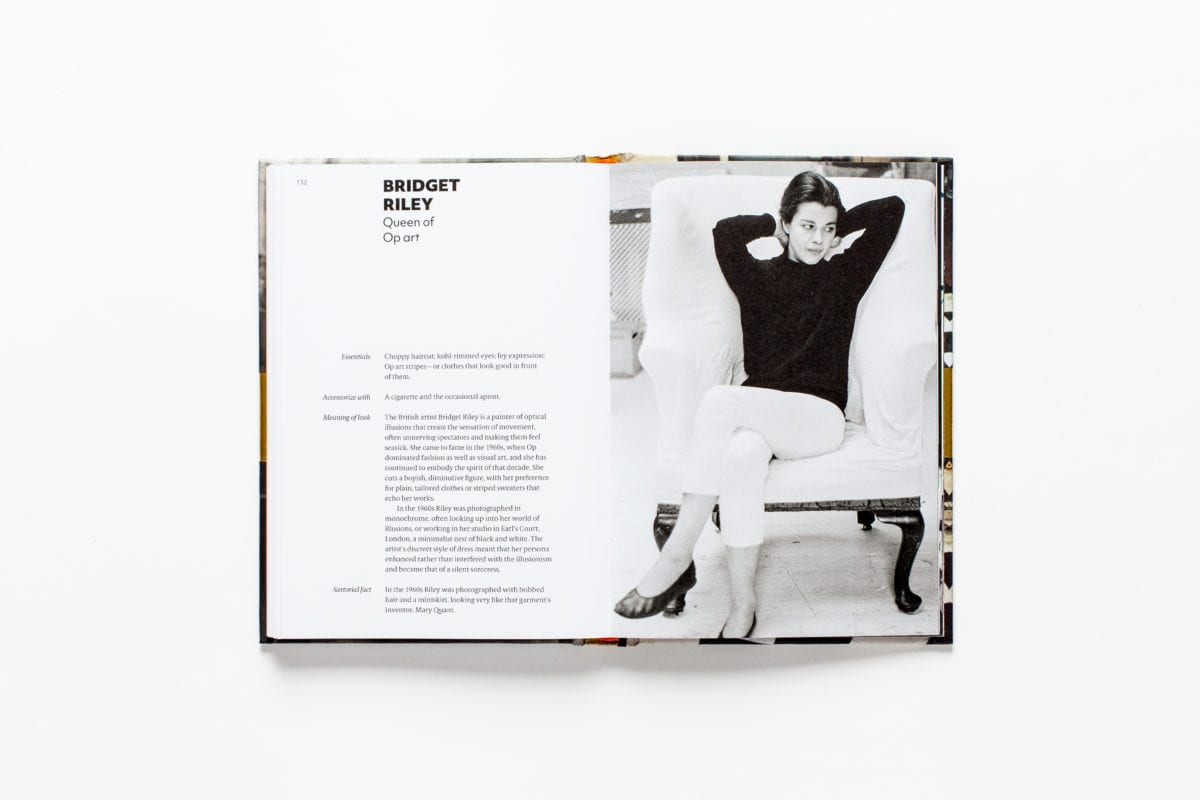

While Sartorial doesn’t dig deep into practices, for all the whimsical lines about Cindy Sherman’s “rhinestone tiara” or Grayson Perry’s “straw-coloured mop”, what it does brilliantly is put the outfits, accessories and outward appearances of the artists succinctly into contexts around their work and messages.

Each page is split into “essentials” (Robert Mapplethorpe’s leather jacket, for instance), “accessorise with”, the “meaning of the look” and “sartorial facts”. Some of these facts are little-known-tidbits, while others riff off the iconic characteristics we know and love/loathe. Some are hilarious stabs in the dark—the page for Banksy (a brave inclusion, for obvious reasons) states: “Each time the media claim they have identified Banksy, he appears to be an advocate of normcore.”

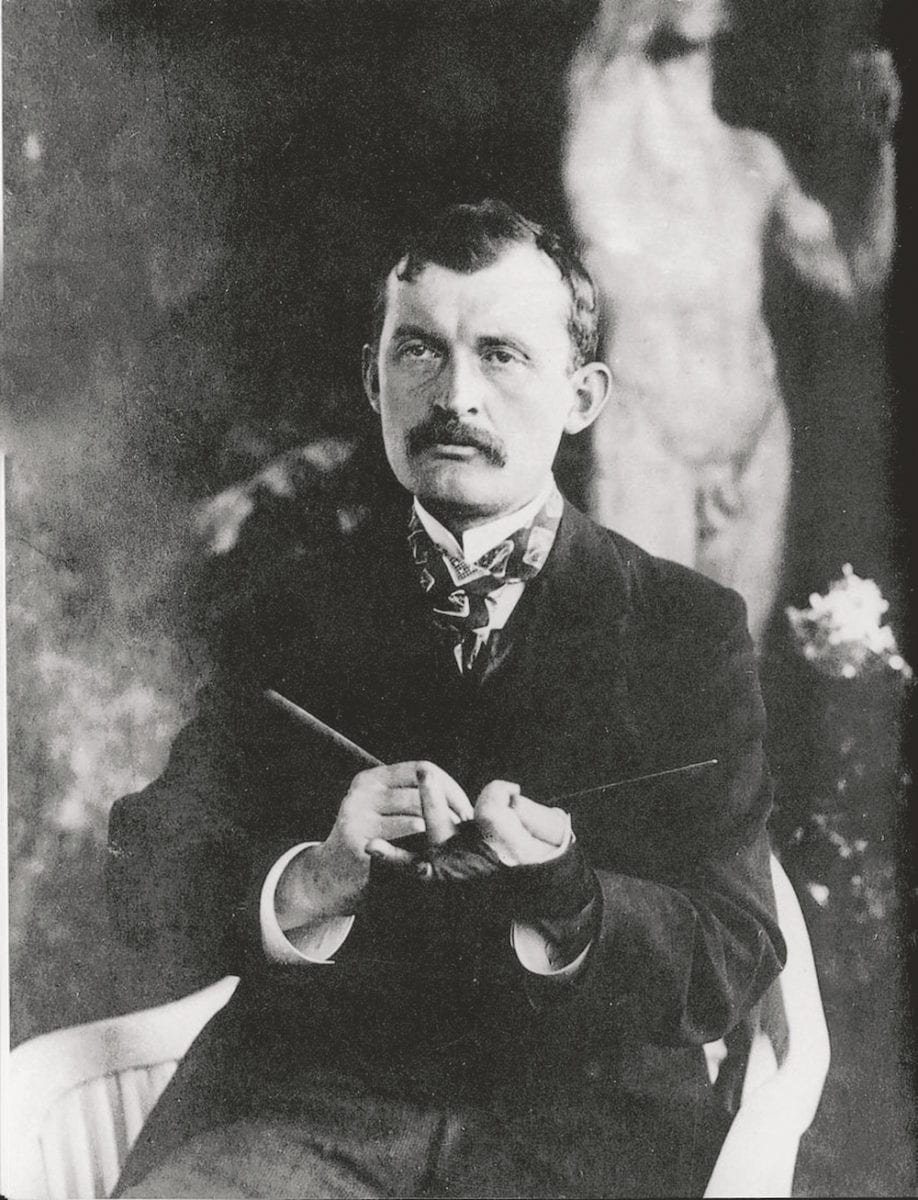

- Edvard Munch, Norwegian artist. GL Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

- France, circa 1932. Tamara de Lempicka,French-Polish painter with a hat designed by Rose Descat, Paris. Photo by Imagno/Getty Images

But it’s the “meaning of the look” stuff that offers the most insight, setting established visual shorthands and/or semi-pretentious Halloween costume ideas in their wider social and political context. While there’s little to be said about Bauhaus artist Marianne Brandt’s outfits, what is interesting is the description of how her look changed over time. “During her career, Brandt appeared in varied sartorial guises, evoking different types of womanhood,” the book proposes. Her early 1920s “androgynous pixie cut” and metallic jewellery is described as Brandt’s most “utopian” personal aesthetic, echoing the feeling in the wider world in the inter-war years. By the “more conformist” 1930s, says the book, she’d softened her look, growing a blonde bob and choosing more delicate accessories. Her clothing was even less ornate when she took up a post as a fine art lecturer in Dresden after the second world war, “though it continued to reflect the light, as she positioned herself as a luminous agent of progress”.

Sartorial is a lot of fun, and a delightfully unserious look at the art world and how its brightest stars present themselves to the world. The imagery is wonderful, and drives home just how entrenched certain signifiers have become in our visual lexicon—Hockney’s glasses or Frida Kahlo’s headdress alone are instantly recognizable icons. This is a book that’s also gleefully unafraid to send up the more ridiculous sides of the art world that made it possible: “[Jeff Koons’s] alternating wardrobe of slightly lustrous suits and white t-shirts indicate a man who has ‘made it’ and no longer needs to get his hands dirty. Koons’ enormous grin reverses the Romantic notion that artists are melancholic.”