On a flight back to her hometown of Sarajevo with her blandly heteronormative, infuriatingly stoic boyfriend, Asylum Road’s protagonist Anya loses her phone and her notebook. In a moment of forgetfulness and exhaustion, brought on by illness the night before, she accidentally leaves them in the pocket of the cheap Ryanair seat. A minor relatable nightmare. In her grief for this notebook, Anya describes how Jenny Holzer’s Lustmord (1993-4) is “reproduced” there. She imagines the person who will find her notebook and what a ‘find’ it will be.

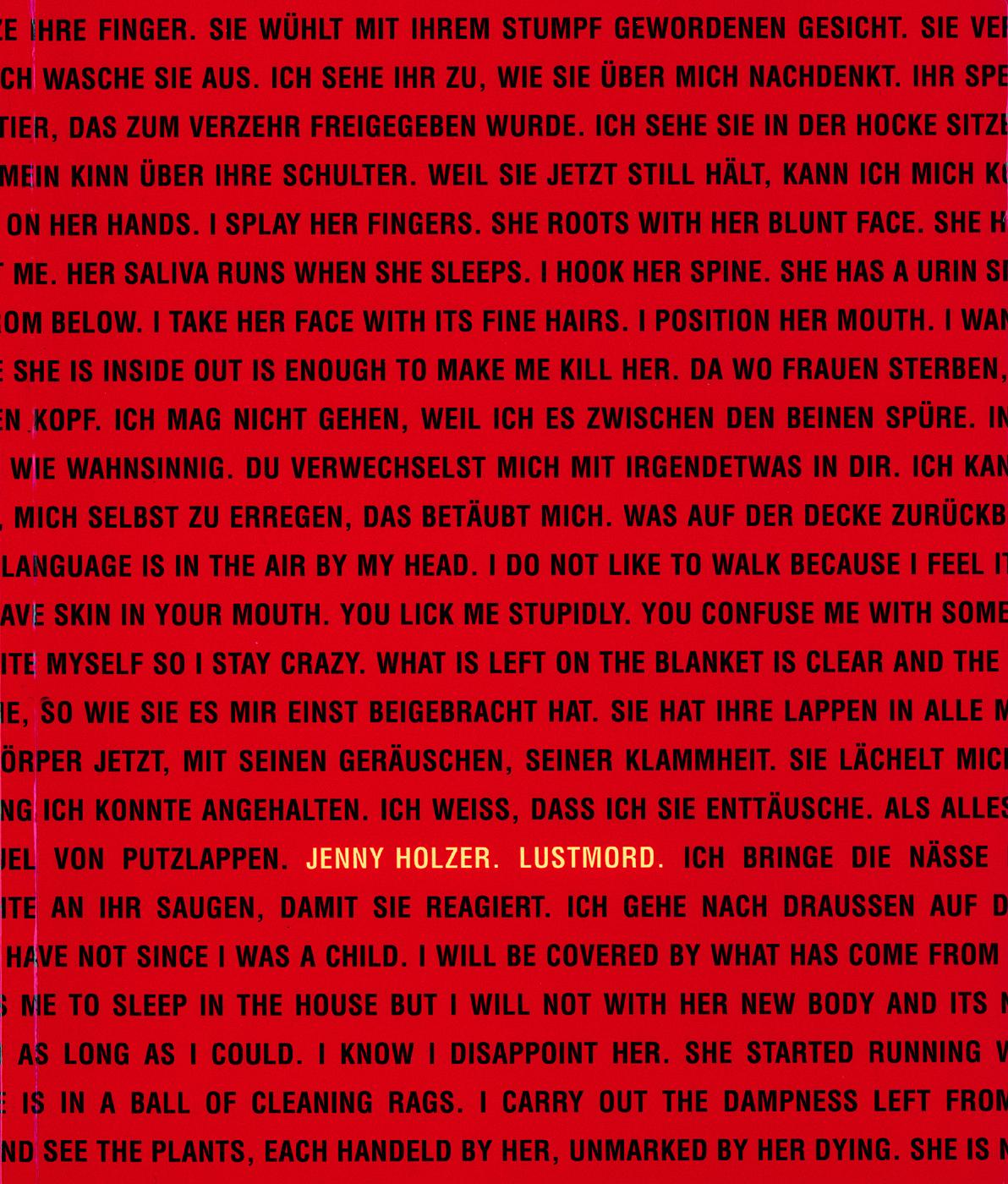

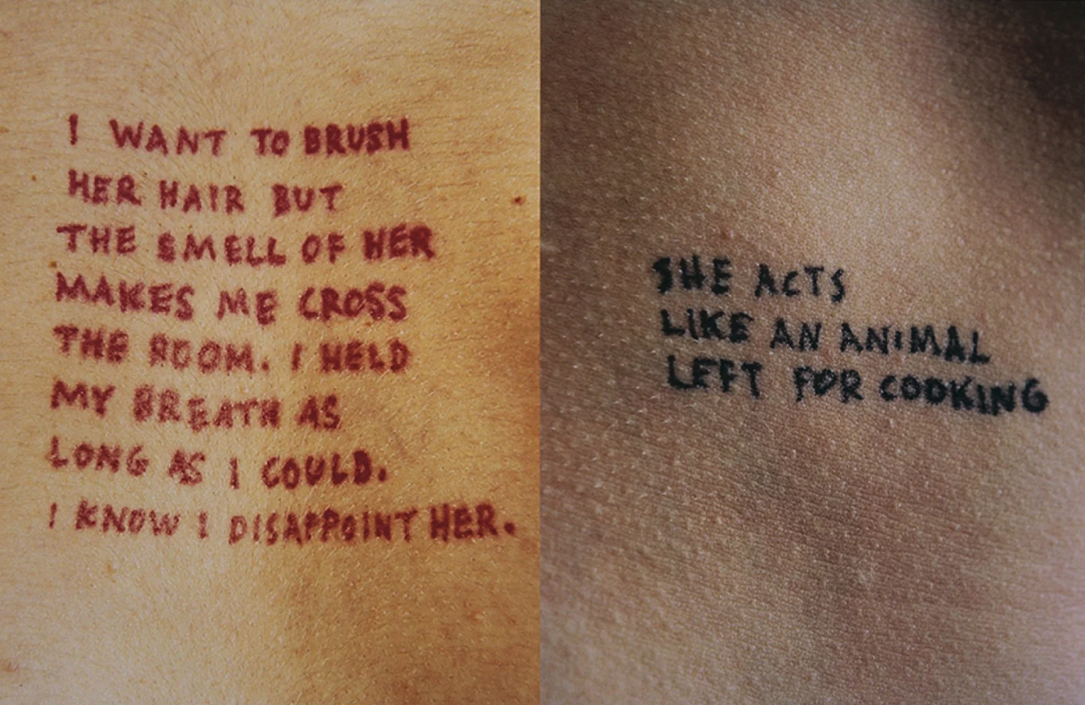

Lustmord is a series of poems by Holzer that responds to the ethnic cleansing and methodical rape and murder of women during the Bosnian war. The piece itself takes various forms, from the Lustmord table with bones arranged upon it, to poems to prints of written statements across various, unknown and distended, amorphous pieces of skin. Holzer maps these war crimes across the body, charting this unspeakable trauma, picking apart the impossible incongruity that lies between rape and its symbolic or representational iterations.

Olivia Sudjic’s Asylum Road starts in France with Anya, an art history PhD student, and her partner Luke, as they drive and listen to true crime podcasts, strangely silent, not quite comfortable in each other’s presence. A series of journeys follows: to Cornwall to stay with Luke’s conservative family; to Croatia; to Sarajevo to visit Anya’s family and to introduce them to her fiancé; and finally to Cambridge, where Anya reconnects with an old boyfriend. We follow a proposal, a break-up, an abortion, a move into a Peckham-based commune and finally, a cataclysmic ending.

“Asylum Road seems to question how violence and geopolitical trauma subtend the boundaries that govern our intimate lives”

Throughout, Asylum Road seems to question how violence and geopolitical trauma subtend the boundaries that govern our intimate lives. National borders and nascent contemporary political violence are mapped upon bodily and psychic boundaries, between Anya and her various relationships; the book’s blurb reads, “what happens, and who do we become, when the borders governing our lives break down?” At points, Asylum Road feels like an exercise in how we narrativise contemporary political reality, and perhaps, what the book initiates is a question of what might be the ethics in doing so. Contemporary life is refracted by the silences and implicit nods towards Trump and rising fascism—“He’s like a president from a TV show”—Brexit, and past and present nationalisms: “a fan of borders but not boundaries”.

- Jenny Holzer, Lustmord Table, 1994; human bones, engraved silver bands, wooden table. Courtesy of the artist and Sprüth Magers. Photographs provided by the PinchukArtCentre © 2016. Photographed by Sergey Illin

The trauma of Anja’s life, before and after leaving Bosnia and Herzegovina, is tacitly and quietly peppered throughout the novel: in her dependency on Luke, her inability to articulate her desires, her floating dissociation. In all these moments, we witness Anja’s inability to fully escape, and yet fully articulate and understand what has happened to her family and her homeland. Like Lustmord, where through ambiguous pieces of skin and vaguely violent sentences etched upon them—“I am awake in the place where women die”—the trauma inferred by the piece is displaced, inconceivable. If trauma is defined, as Cathy Caruth argues, through a “legacy of incomprehensibility”, then Lustmord and Asylum Road figure trauma’s inherent incomprehensible latency through the body.

“We witness Anja’s inability to fully escape, and yet fully articulate and understand what has happened to her family and her homeland”

The control the past holds on Anja is played out in how she disciplines her body; the immediacy of any past violence prickles across the character’s skin as she picks the hairs on her jawline or denies her hunger as a “form of security”. The novel is propelled by the apathetic tonal cadence of someone who maybe skipped a meal at lunch, and instead chose a large cup of black coffee.

Anja’s thin body seems to recast the spectre of the pale, sickly Victorian woman into a modern image of the bourgeois, Peckham-dwelling twenty-something Bougie London Literary Woman. Throughout, Anja lacks any stable relationship with food; it is eyed suspiciously, thrown up or turned into a game (“What Can Anya Eat? The answer was usually one small plate of cucumber, thinly shaved.”) She dislikes any form of soft vegetable or fruit; segments of clementine disgust her, as do the rolling, escaping plums of a “wide” woman aboard a Ryanair flight, and the thought of an “unmediated slice of orange” makes her gag.

While I am cognisant that using Sally Rooney as a tide-mark for comparison with other introspective novels by other young women can be a lazy critical start, the portrayal of Anya does bear a canny resemblance to the protagonists of Rooney’s novels: melancholic, quiet, fragile and skinny women with their “protruding collar bones and dainty wrists”. Yet somehow Anja offers still something more abject, finding it openly satisfying to feel herself “wasting away”. She constantly wills herself to disappear, to oblivion, the madwoman in her Asylum Road commune, hysterical, driven to desperate measures. Both Rooney and Sudjic’s characters provoke in me a strange, visceral reaction. Stuff just seems to happen to them. I find these helpless, passive characters distressing and impossible; they make me want to shout at them to get their act together, to intervene, to tell them that they shouldn’t allow themselves to be treated this way.

“The novel is propelled by the apathetic tonal cadence of someone who maybe skipped a meal at lunch, and instead chose a large cup of black coffee”

This helpless affectation is not exactly vulnerability. I don’t revile Anja’s fragile identity as a result of some internalised misogyny, but it is that such fragile femininity is so often figured through socioeconomic and political stakes. On their return from Sarajevo, Luke and Anya’s relationship breaks down in that unspoken, tacit way that many heterosexual relationships do in contemporary novels. “Finally I prompted him, so is this over? and he just sat there in silence again, before finally saying I guess – despondently as if it was all my idea”.

As she crosses one border both to and from home, the stability and constancy she finds with Luke collapses as he suggests they take a break. As this relationship fractures, the death of her mother and brother, her swelling depression and dissociation and the political violence of her life eventually come to a head. But rather than tracking the arc of this violence, it feels like background—separate, secondary footnotes to Anja’s psychological and physical state.

“Both Rooney and Sudjic provoke in me a strange, visceral reaction. I find these helpless, passive characters distressing and impossible”

While the novel’s strength is the beauty of the prose and the prickle of its metaphors, it also subtracts histories of political violence and European nationalism, playing them out across the spectacle of Anja’s fragile, thin, female body; her destructive tendencies; her starvation; and in the way she allows Luke to ignore her while simultaneously using him to define and comfort her as she moves through the world. “After we collected the bags, and the train pulled into Liverpool Street, he finally took my hand. The chokehold loosened,” Sudjic writes.

Having exposed her family and “the child I turned into with my family”, Anja has to keep asking if Luke still loves her. She tugs at his waistband to “make it up to him” in a hotel room, and while revelations of such intimate vulnerability are candid, these moments are plotted much more conspicuously than any of her memories and flashbacks to the Bosnian wars and its aftermath. If Holzer’s Lustmord asks us to consider how we represent iterations of trauma, Asylum Road attempts to figure the inherent latency of trauma across the fractures and fissures of contemporary life. The political, state-sanctioned violence of the Bosnian wars—the siege of Sarajevo, the shellings, the death of her brother, uprooting and seeking asylum in Glasgow (punned upon throughout)—are conveniently refracted, becoming a composite of the personal in a way that works to undermine, rather than distil, such devastating world tragedies.

Come As Softly is a book column by Bryony White on intimacy, desire and sex.