I grew up describing myself as a futurist. I daydreamed about how my life would be tomorrow, in five or twenty years. I was always looking forward, never taking a step back to analyse the past. I was critical of it, I considered it meaningless, irregular, and destructive.

As an art foundation student, I attended lectures featuring slideshows filled with lavish artworks, which I was told held an influence on the evolution of visual culture. While I sat there admiring the skills and craftsmanship of the artists, they made no lasting impression. To me, all these works were merely artefacts, consigned to history.

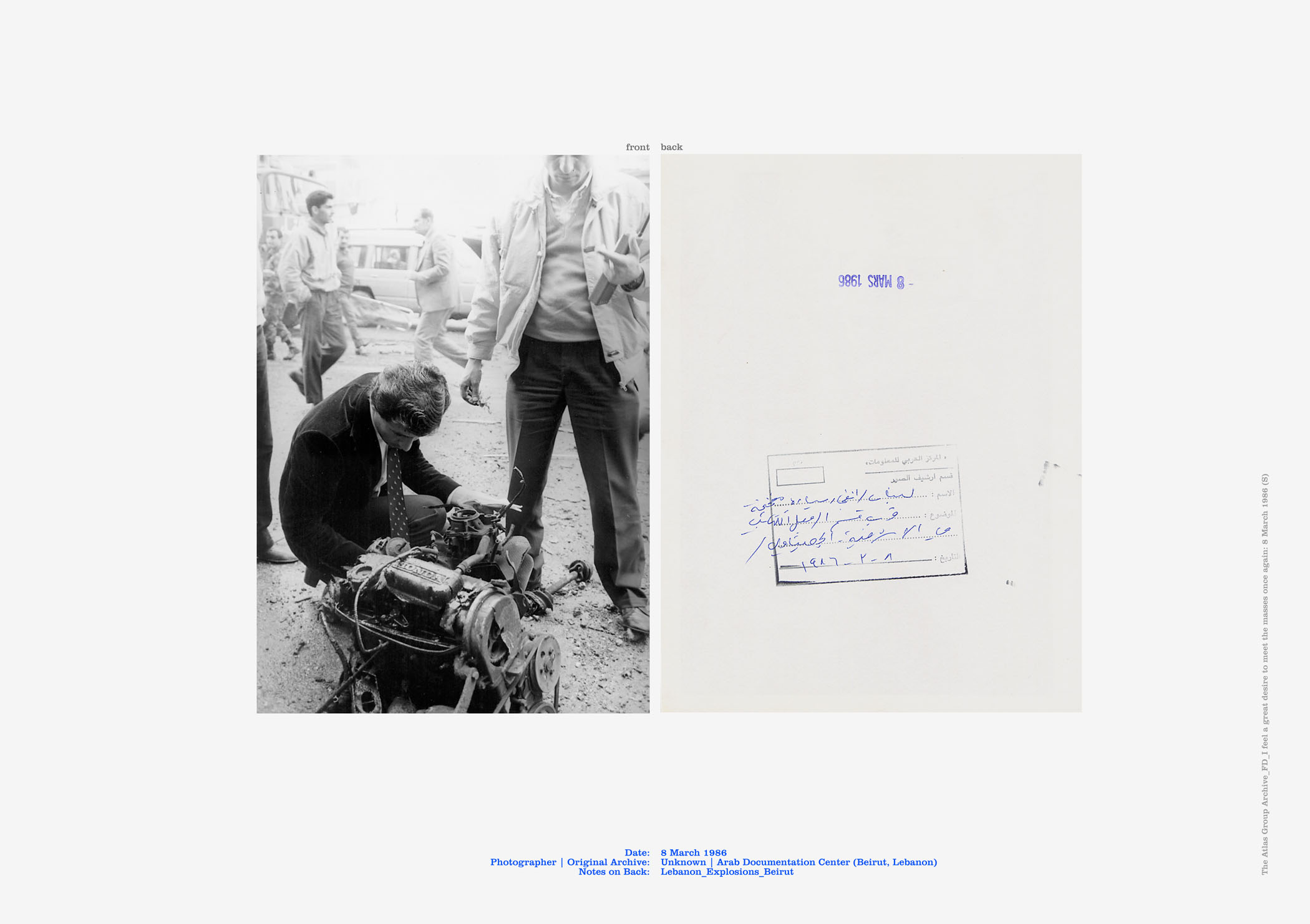

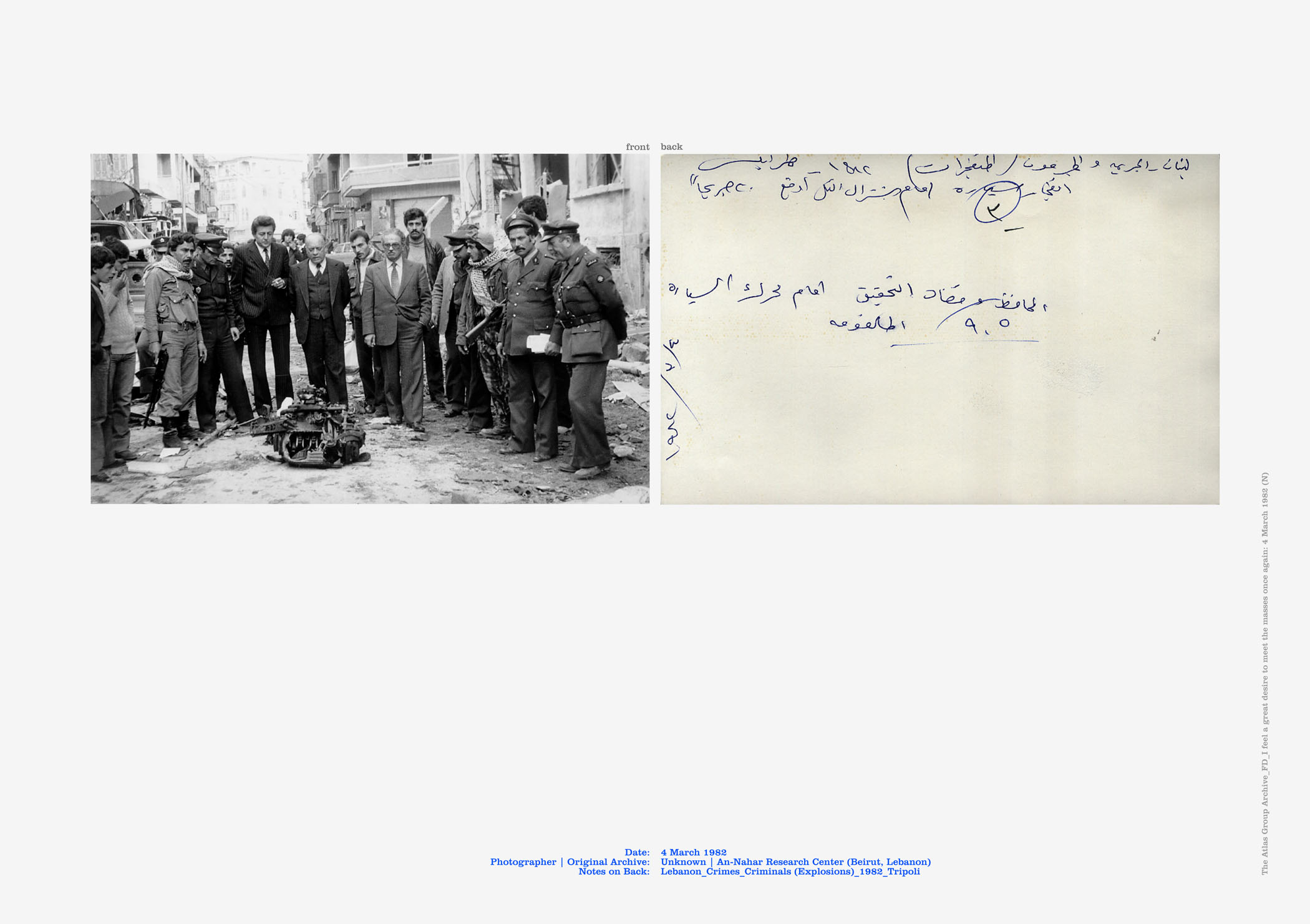

One day, an entirely different work popped up on screen. Walid Raad’s My Neck is Thinner than a Hair: Engines (2000-3) consists of a rectangular display of a hundred archival records featuring the aftermath of car bombs that took place during the Lebanese Civil War (1975-90). Each entry includes a black-and-white photograph of a blown-up vehicle’s engine, many of which were found scattered throughout Beirut, often metres away from the site of the explosion.

The photos sometimes depict military officers or concerned civilians inspecting the remnants, bearing witness to the violence. Raad sourced these journalistic images in newspapers and reprinted them alongside handwritten notes that include the date, name of the photographer, and a file number that relates to his far lengthier project The Atlas Group (1989–2004).

“The history of my country has been damaged, wrecked, and sold”

I felt a strange closeness to My Neck is Thinner than a Hair: Engines, and a particular affinity with these reclaimed archives. Where or how the work was displayed, and even the specificities of what it was about, wasn’t important to me. I was fixating on the fact that a narrative was being told through these records. These documents are vital in telling the hidden stories of people caught within conflict. It was as if the work was revealing more about me than I was learning from it.

I am from Kurdistan Iraq, a country that has been living with different forms of conflict for decades. Corrupt leaders, invasions, wars, protests, all compromise the state of the region’s official archives and documents. The consequences of the gulf war and the US invasion of Iraq were the mass lootings of museums, libraries, and ministry offices. In 2003 looters broke into the National Museum of Iraq where the largest artefacts of Mesopotamian history resided and stole thousands of pieces. Today, many of them have still not been recovered.

However, some of these objects appear on online auctions, being sold for as little as $50. Through conflict, opportunities arise to displace history and cultures from their original homes. When I was young I thought these events were the result of being from somewhere that no one cared about. Whoever the looters and thieves were was not important. The consequences sent a clear message: that these cultural objects were not of value.

The history of my country has been damaged, wrecked, and sold. Entering young adulthood with the knowledge that my past consists of fragmented and torn pieces made me feel bitter. It results from years of watching inconsistent reports on all that is being taken away, and an inability to understand and navigate the passages of history.

I became disinterested in learning or engaging with historical materials (the idea of the archive) even on a personal level, because I experienced the fate of my country as narrated through numbers: the years that wars began and ended, the casualties, the number of deaths. Among all that data, I questioned where the accounts of writers, artists and documentarians were. Where do they exist among all the cold and uncompassionate history?

“I questioned where the accounts of writers, artists and documentarians were. Where do they exist among the uncompassionate history?”

The Middle East in general lacks stability within its archives, due to these conflicts and destruction. The personal narration and subjective stories of history that are told to engage, inspire and shed tears, are scarce. Raad bridges the gap, by fulfilling the role of artist and historian, preserving the history that is not taught.

Through The Atlas Project he created volumes of works chronicling the Lebanese civil war, involving transcripts, official documents, photographs, news footage, videos, graphics, text, collages, and performances. He played around the fine lines of fact, historical accuracy, and fiction, at times reimagining real-life events with video works of hostages that were produced using actors and a script.

I find that these fantastical elements possess innate emotion. People’s perception of history is not based on facts or objective truths but rather discontinuous and inconclusive narrations, built on personal interpretations of witnessed events. As Raad says himself, “what we have come to believe is true is not consistent with what is available to the senses.” In works such as My Neck is Thinner than a Hair: Engines

he takes it upon himself to collect images and ask questions, holding on to information that would otherwise be lost.

“Raad’s project taught me to make sense of the fragmented history that I once was so critical of”

In the same year that I encountered this piece, I was inspired to complete my diploma with a personal project about my family’s anecdotes and old photographs. Within the stories there were accounts of wars, protests, and moments of historical significance. Following Raad’s methodology, it wasn’t the accuracy of the events or the supporting of a single side of the conflict that was relevant, it was people’s recollections and experiences.

Today, I aspire to become an archivist. Someone who documents narratives of the past and who records hidden people’s memories. Raad’s project taught me to make sense of the fragmented history that I once was so critical of. It helped me appreciate the stories I would have otherwise missed.

For the longest time, I failed to understand that history is not a linear path of facts and solid evidence, but a fluid collection of varying objects, tales, people, and memories. Now, when I look to the future, it is one that is made up from the materials of the past.

Images © Walid Raad. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

Shang Salah is a writer and Media Production student based between Kurdistan, Iraq, and England