What is perspective? Humphrey Ocean should know. The painter—whose vernacular includes people on the tube, herring gulls, armchairs, Peckham Rye, Dulwich, Philip Larkin and Tony Benn—has been the Royal Academy’s Professor of Perspective since 2012, a position that belonged to JMW Turner for thirty years in the 1800s. Not that JMW Turner was very good at it; he famously took three years to prepare each course and hence only managed to deliver twelve lecture courses in his three decades, which audiences complained were mumbled and disorganised.

Perspective in art is about creating an illusion: in the traditional sense, representing three-dimensional objects on a two-dimensional surface, in a way that makes them appear to reflect the “reality” of what we see. Linear perspective—an idea introduced to art in the Renaissance era—posited Leon Battista Alberti’s one-vanishing-point system, a basic rule of perspective still used by many artists today.

But beyond the technical—viewpoints and vanishing points, geometry and angles—perspective is something much more personal, and these days, politicized. Perspective is a process of learning about the world in relation to where we stand. As Ocean so beautifully puts it in his new book, “When you study art, it is your version and you learn to value yourself.” His version of things hasn’t always pleased others—he was once rejected from the Royal Academy’s summer show. His painting of former Deputy Prime Minister, William Whitelaw (a portrait that now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery, where Ocean has had several exhibitions) was one of the gallery’s “most problematic commissions,” and did not go down well with Trustees, who proclaimed, “that’s not our Willie!”

“Perspective is a process of learning about the world in relation to where we stand”

Ocean, as Ben Thomas puts it in an introductory essay to Ocean’s monograph, shows us things we already know “but now we are really seeing them”. It is the intensity of Ocean’s gaze on things, both banal and important, that is so unique. Scientifically so, in fact: Ocean offered himself up as a guinea pig for scientific testing, allowing John Tchalenko to investigate the movements and blood flow in his brain and his eye fixations while he painted portraits. Compared to the non-artist spectators, the studies found that Ocean looked less but with greater intensity—leading Tchalenko to conclude that he was thinking while looking, and not simply emulating what he was seeing.

Ocean has been a quiet but consistent contributor to the British art scene since the 1980s, when he had his first solo exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery, followed by exhibitions at the Tate Liverpool and the Whitechapel Gallery. He has worked at a steady pace and exhibited regularly, but not often, and without too much critical attention. It is a fact that seems strange when considering how distinctive the work he has produced over the decades, laid out now in this publication.

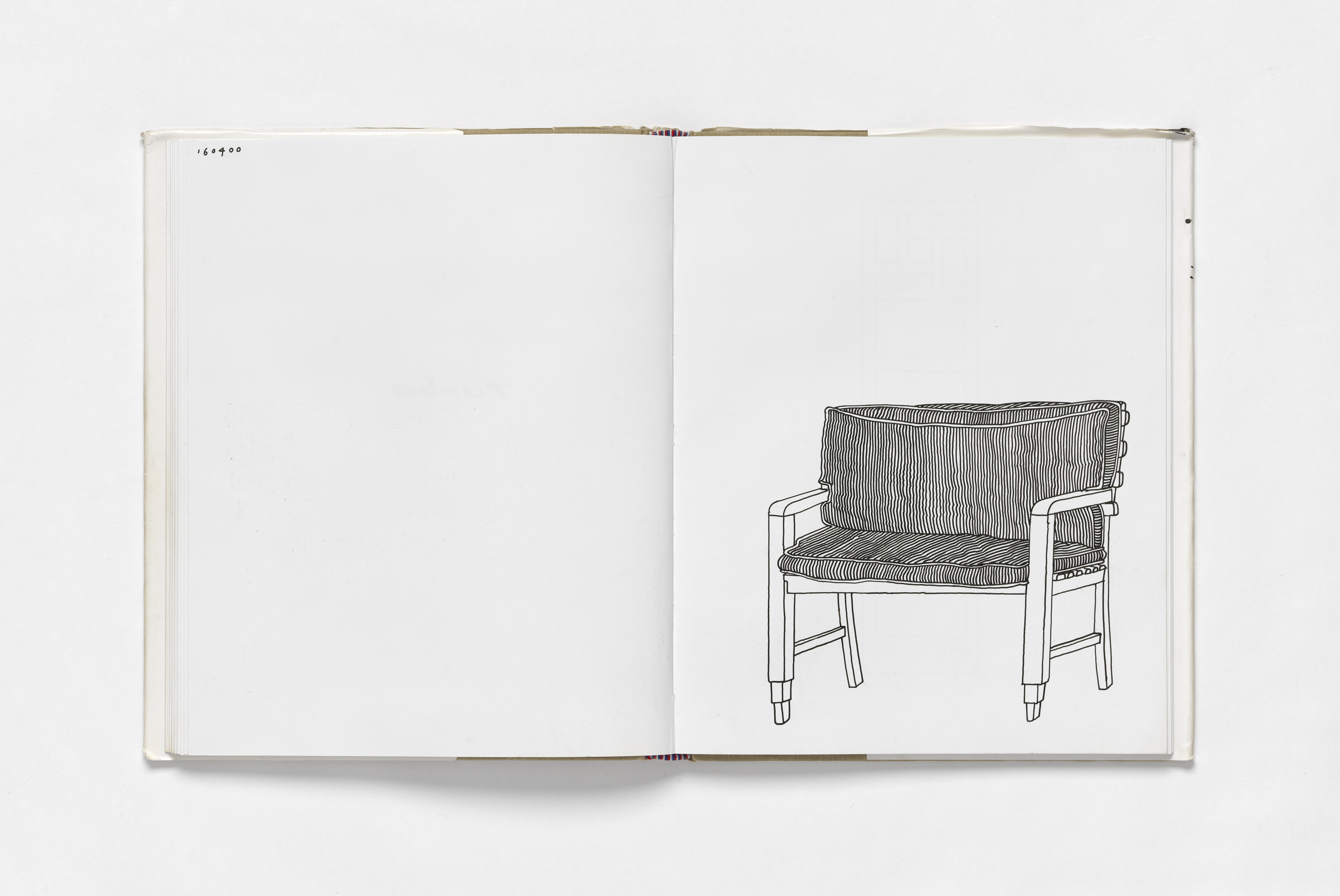

First, there is his palette, a quintessentially British palette, with hues of murky greens and pinks, dusty greys and blues. Then there is the rhythm of his painting, which is fast-paced and free—even if he has sometimes laboured over a painting for more than a year. It’s easy to see why his portraits are his best-known works; they’re majestic observations that keep you coming back to travel the faces—especially in his portrait series, A Handbook of Modern Life. But there’s something just as compelling about the solitary objects he’s painted, a kind of thirsty inquisitiveness about things that might otherwise be passed over as perfunctory. This is a good lesson for life.

“There’s something just as compelling about the solitary objects he’s painted, a kind of thirsty inquisitiveness”

Not everyone will relate to Ocean’s perspective, of course. He admits that “he paints what he knows”, and there is, at times, a boyishness to his work that, from my own perspective, is harder to relate to. But that isn’t the point. What you take away from Ocean’s book is how wide the world is, when it can sometimes appear small; how living in the same city—London, in this case—can look so different. Ocean’s book is a part of his version of the world, and he never lets the viewer think it’s anything more or less than that.