Chances are you’ve spent time with Humphrey Ocean’s painting; you might have passed one in the National Portrait Gallery, the Tate Liverpool or the Whitechapel Gallery. Best known for his paintings of people, among them Paul McCartney and Randy Lerner (but are they portraits? see below) the English artist has a distinctive touch, fluid and loose; he takes liberties with reality but it remains convincing. His particular sensitivity to nuances in colour struck a chord with artist Unga, who visited Ocean at his studio in West Norwood, where the older artist is still having fun with paint, and jumping between design, medium and matter. There, the two painters from different generations and countries sat down to discuss painting, life and plastic bags.

Is this body of work prepared especially for the exhibition at Sims Reed Gallery, or did it come naturally out of the studio?

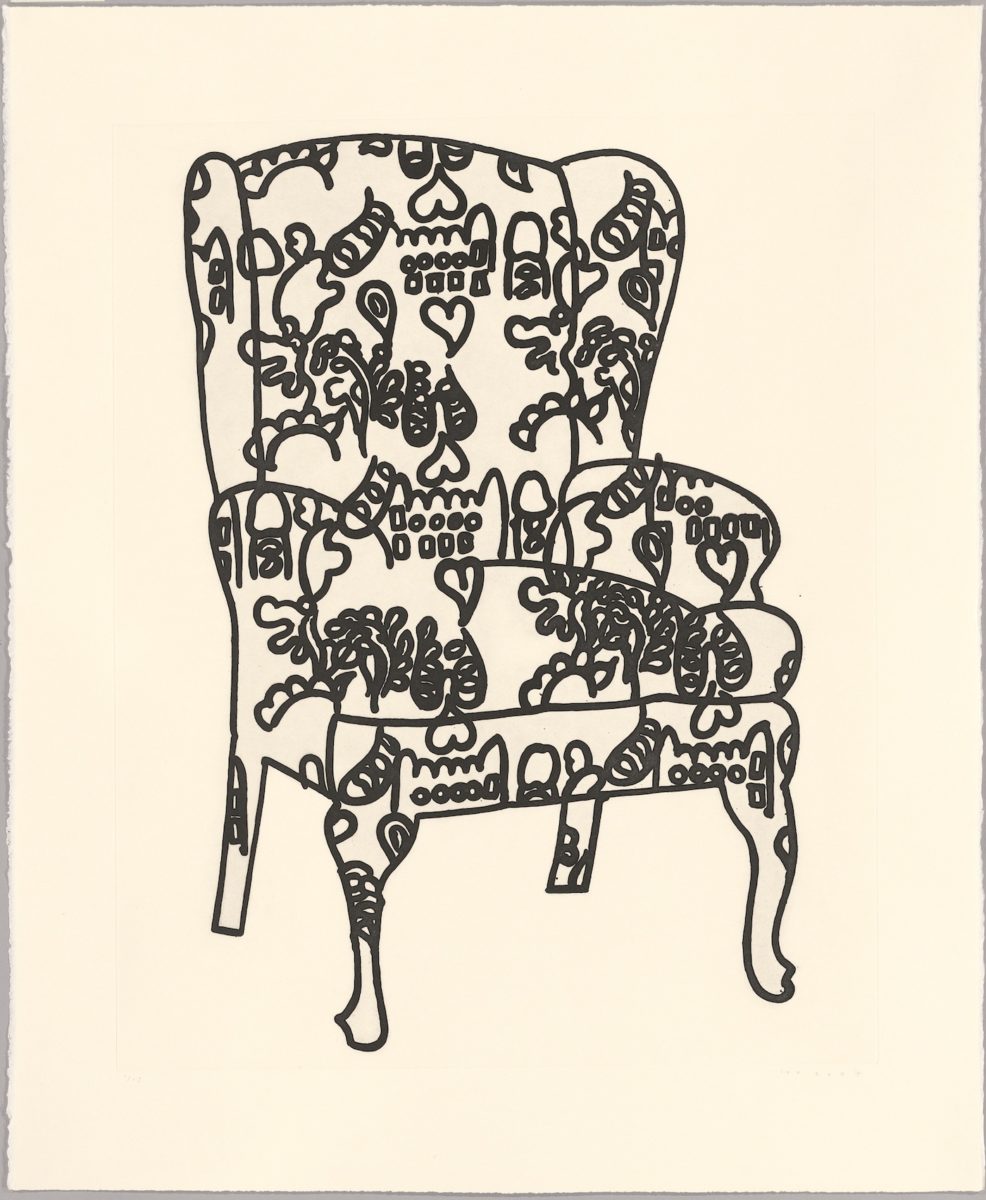

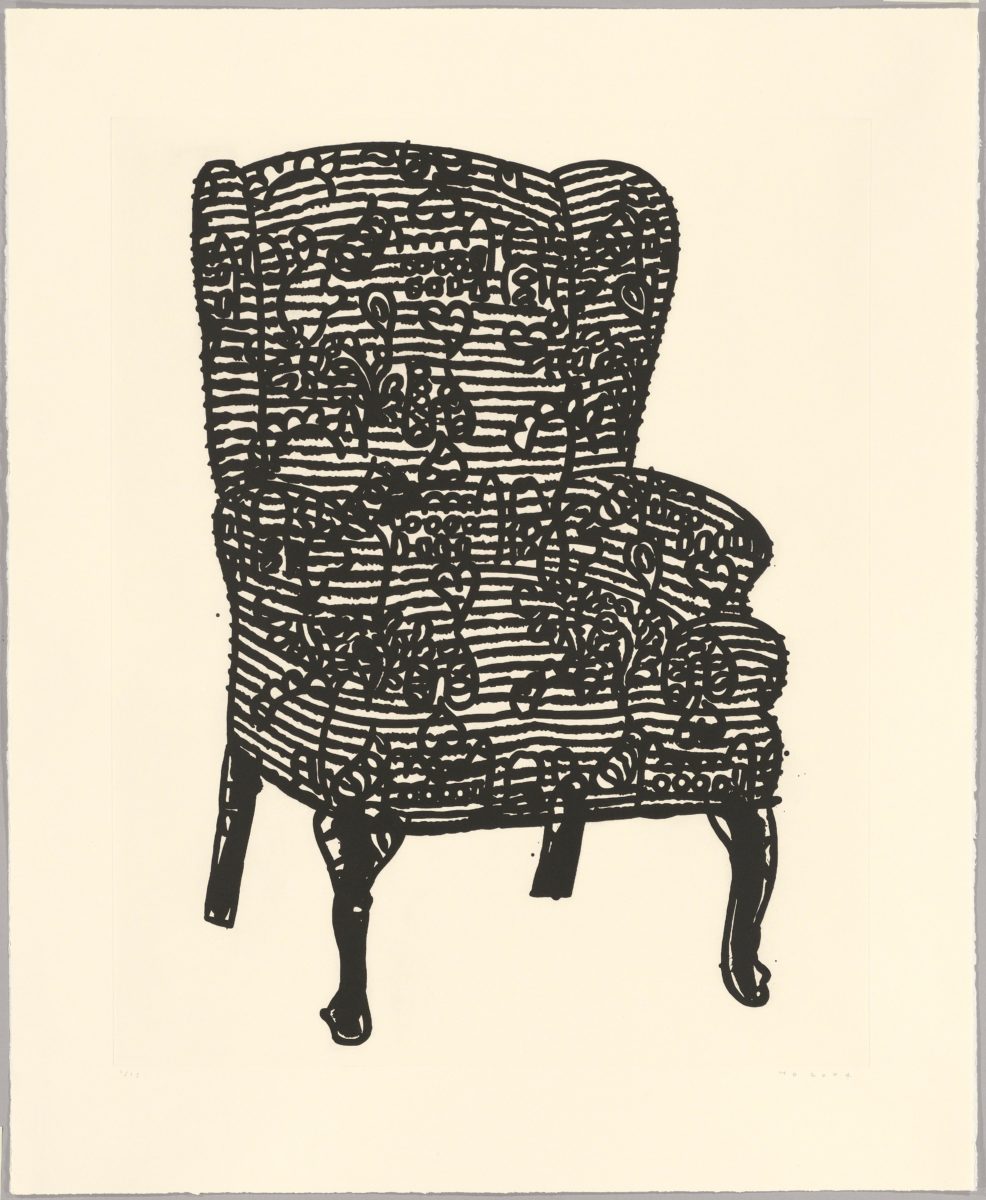

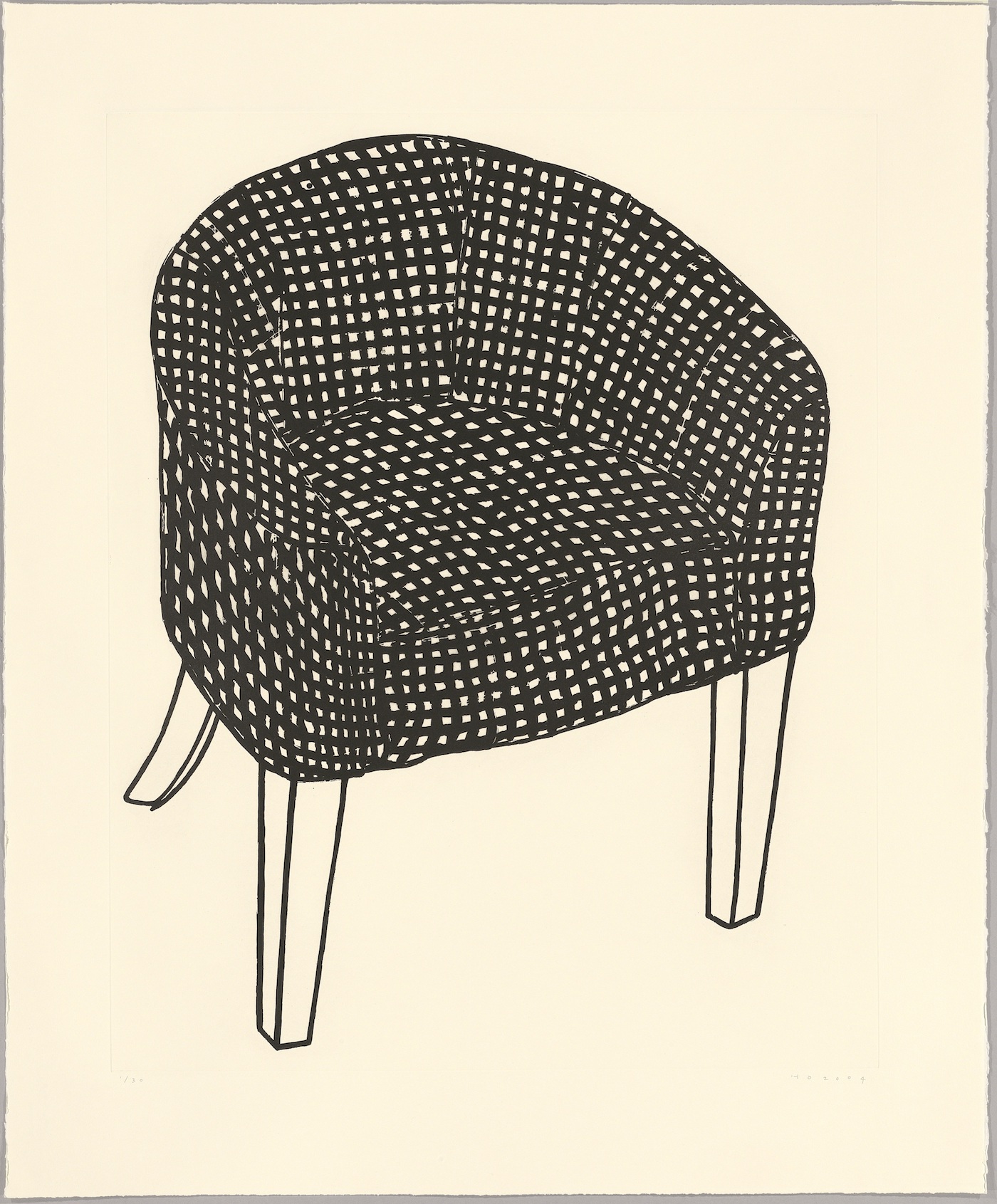

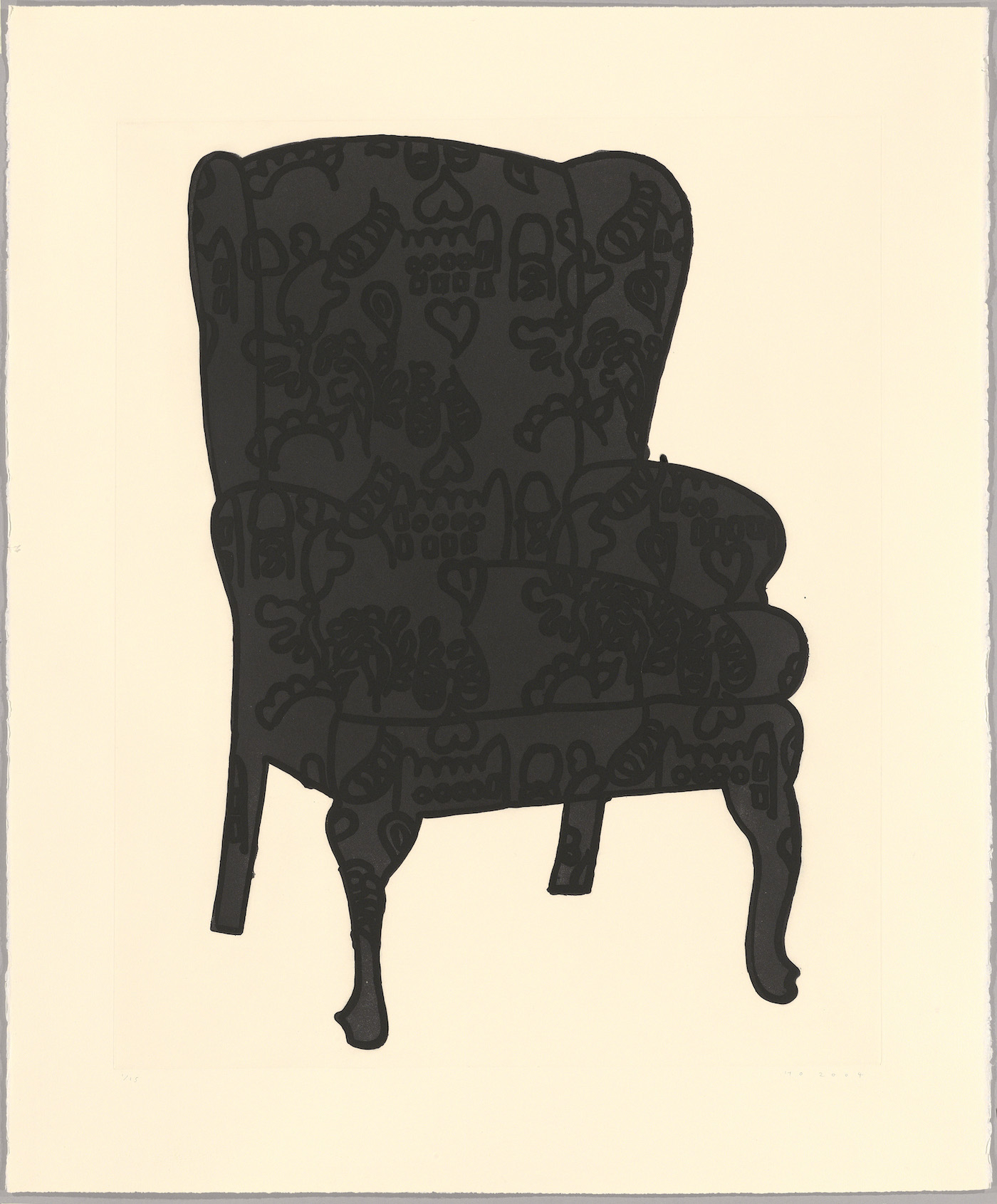

It came naturally. Petra at Sims Reed Gallery saw a show of forty portraits I did at the National Portrait Gallery [A Handbook of Modern Life] and she had those in mind. Sim Reed is a beautiful bookshop, but they do exhibitions there. They have nice stuff that’s different to me, but good stuff, so I thought: Yeah, I can do that. So she’s chosen some things I’ve done over the last ten years and I’ve done a new print called Violet Chair. She’s also showing some new drawings I made in the last year.

Do you feel comfortable with someone curating your work, is it easy for you to let go? You know what I mean..?

Yeah, I know what you mean—am I a control freak! Yes, I am. One of the things I’ve learned is that when a curator works in a gallery they know that gallery, they know which wall is a wall people go towards—they know the geography. So I tend—and not everyone does this—but I like to allow them to hang. That brings something new; to me, to the work.

I’ve Got No Idea Either is an exhibition of portraits, then?

There are no portraits in there—but there’s a very strong human presence, as I hope there is in all of my work. Because actually portraits, people are at the centre of what I do. I don’t want to paint people all the time but people are the source of everything. We’re mystified by trees, animals, nature—but what we contribute to the world… that is that size for a reason [indicates towards a pencil].

- Left: Love Chair, 2006. Right: Stripey Love Chair, 2006

So it’s still about people, even though there are no portraits in the show?

I find that an extremely good and difficult question. I don’t quite know what a portrait is, but I think a portrait is of a person. You cannot say it’s a portrait of a person if it’s a painting of a car, even if the car is designed for that person.

Portraits are perhaps your most recognized body of work—but is there a place for painting portraits in 2018?

I think if there’s still a place for people—if we haven’t been replaced by Artificial Intelligence—then there is a place for painting portraits. Whatever you do you try and bring something new to it; you don’t even have to try, you just have to be yourself. I think if you try, that’s too much control as it were. If your dirty mind is at work when you’re looking at something then you’re going to take what you want from it. That’s what makes my portraits look different. I’m not going to say I’m not going to paint portraits because that’s been done before, they’re old hat—because Titian’s done them, Rembrandt’s done them, because van Gogh’s done them—that’s not a reason not to do them.

When people see a portrait and they say “Oh, does it look like so-and-so?”, which is why a lot of portraiture has become photographic now—because people’s idea of truth is the camera, a dead likeness. What a bankrupt idea that is! Instead of allowing the camera and photographs, beautiful things in themselves…

“There are no portraits in there—but there’s a very strong human presence, as I hope there is in all of my work. Because actually portraits, people are at the centre of what I do.”

Why do you paint?

Painting, I’ve read for most of my lifetime, is under threat, but the threat came 150 years ago when someone wrote that painting is dead. Paint is mineral, it’s like bodily fluids or something, it’s there, under our feet, and when we dig it out and make a notation, some graphic notation with it, we’re saying what we think. Paint is dirty, it’s the equivalent of what we feel. Computers make everything look fabulous, but sometimes you don’t want that. Paint is very versatile, it can be grungy, glossy, matt. Then people like you come along and shift it and start to pull it apart—painting on a wall…

I’m looking at you at the moment, I’m just looking at your eyes, because that’s how we communicate—I wouldn’t be saying this stuff if you weren’t in here. That’s how important another human being is. It’s not a bad start is it, there? And you work downwards. I think as a subject, it’s a good place to start.

I agree—and I find in the end human faces are the most interesting to paint.

A friend of mine went for an audition with Fellini. He didn’t get the part, but he went for this audition at the Hyde Park Hotel. And Fellini said to him, “film is faces.”

That’s beautiful.

Would you do a portrait of Donald Trump if he asked?

Yes, why not. He’s a human being. I would be fatally fascinated—there’s no such thing as an uninteresting person. He’s politicized us, the same as Brexit has over here. There’s an equal and opposite reaction. I think I did a drawing of Trump and of Kim Jong-un. They’re nothing if not imagery. I’m utterly certain—I’m an old-fashioned socialist, but I’ll drink with anyone in the bar, just to see, let’s move the game on. I’d get into trouble, I know. You’d write about it in Elephant magazine, “Humphrey Ocean wants to paint Donald Trump”, but he doesn’t! I’ll make my own mind up.

One of the things I like about your work is you leave a little bit of room for growth—something I find really hard to do. You need balls as well to say no, that’s it, it’s finished.

I have balls… One of the things I learned, not just because I used to play the bass [in Kilburn and the High Roads] but when I go to see a concert with a group playing and all the instruments drop away and there’s just the bass, the whole audience starts joining in—because people are included. If there’s a wall of sound, they’re just recipients—but if there’s one instrument playing, people can add the rest for themselves. You don’t want to grab people by the collar and start jabbing them like the man in the pub after a few beers.

Have you ever ruined something by doing too much?

Oh yeah, yeah! Get rid of something!

“Paint is mineral, it’s like bodily fluids or something, it’s there, under our feet, and when we dig it out and make a notation, some graphic notation with it, we’re saying what we think. Paint is dirty, it’s the equivalent of what we feel.”

When I’m creating, there’s one side of me that just does what I think is interesting—but then there’s another side that I think, wait, I need to find a new way to describe this reality. At the same time, it feels like today, when you go to art fairs, that the thing that controls it is conceptual art, and I can’t connect to it. It makes me wonder if I’m in the right field, can I still push painting forward?

I think any art worth its salt is fifty percent concept. Van Gogh was an extremely intelligent person and his paintings contain intelligence—the fact they look like they’re painted by someone digging a ditch makes them even better. When you talk about conceptual art I think you’re talking about things where there’s an imbalance, where somehow the entertainment part has been squeezed out of it. I think equally if it’s too much about the making of it, if there’s no intelligence, that is craft—some people won’t like me saying that—but craft is kind of showing off, I think. You’ve got to have some thinking, you’ve got to have something to say. And the way you say it might make people laugh, cry or bore people—I’d rather not the third…

I think for me what makes you a British artist is the use of different versions of grey—only someone who lives here could have this sensitivity towards grey.

But I can see an orange plastic bag over there, and I know that is orange… Strangely, Lucien Freud, who came here from Austria, has beautiful colour—and it’s English colour but it took an outsider to see that colour. It knocked spots off lots of people who use a tropical aquarium; we don’t live in a tropical aquarium, which is why it’s lovely when you see an orange or a nice yellow, one notices it. Those moments of colour are like stars on the stage.

It’s true, but for me it is something about being here, the grey. In the Middle East, where I’m from, there is beauty in the colour, but it’s very brutal.

When I see it on television, or film, what I see is that baking heat—it’s bleached out actually. If you look at Morandi’s paintings, his landscapes, you could warm your hands on them, they’re so hot—but he doesn’t use bright colour. I think there’s an illusion, and English people especially suffer from it, they go abroad and they think Oh my God! The colour is overwhelming, but actually, it’s not all bright red, yellow. I think like anything you’ve got to walk it straight a little bit, so you can see it clearly. You can make bright colours behave themselves so you can see the colour you want people to see. It’s difficult to talk about it.

When you say it I can completely visualize your painting… but it’s still very grey here and somehow it seeps in.

English people go to India and they buy saris and they wear them over there, and they’re fine, they settle in. You know it’s the land of the sari. Whereas over here, it’s the land of the potato.