Sparked by a dream, Lucy Carless explores art, fame, and technology’s intricate dance with Haring’s legacy and asks: What if he’d faced the digital age?

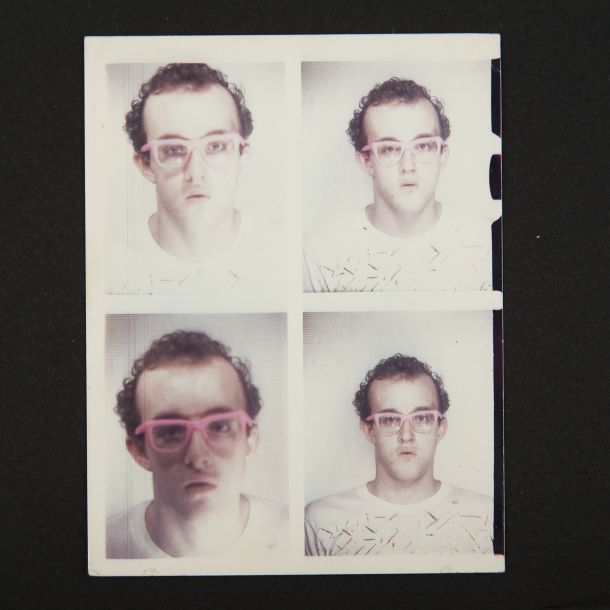

It opens on his face. Round, open eyes encased in round-rimmed glasses; a small mouth framed by a prominent chin; his hair, a smattering of curls. But something is different; this isn’t the boyish Keith Haring I recognise from the 1980s club pictures, arms draped around Andy Warhol and Grace Jones. Instead, he looks older, weathered. He sits in the back of a people carrier with his head resting in the armpit of his lover, a construction of my unconscious mind, whose hand gently strokes Haring’s salt-and-pepper beard. My view is the camera’s eye that follows Haring as he narrates and navigates us through his final years. In the dream, he has lived a little while longer, just a decade or so, long enough to make this film that talks us through art, love, and mortality at the turn of the millennium. Ludovico Einaudi does the soundtrack. Haring considers his legacy as he approaches death, the pride he feels in the art he created, and his desire for a universal community. He shares his anxieties about a technological future and appears to be content to leave this world of computers behind. It closes with the shot from the car: the two lovers intertwined, Haring’s closed eyes, and peaceful smile. We hear his voice: ‘When he holds me, I know I’ll be home’ as the dream fades to black.

I woke up in a world where Keith Haring didn’t live to make his film. He didn’t live to make art in this new and complicated culture, to be cancelled, berated, or to disappoint, to be nipped and tucked in an effort to uphold the face that once made those great works. A voice that said great words. A body that changed things.

“When a gifted artist dies before their time, they are almost seamlessly inducted into mythology.”

This dream came to me in the midst of some pretty intense jet lag and a period in which I had become increasingly interested in Haring’s work and legacy. I had been in Australia for just a week or so and visited the ‘Keith Haring x Basquiat: Crossing Lines’ show at the National Gallery of Victoria. I was captivated by the work, collaboration, and relationship between the two artists, but it was the odd sense of nostalgia the exhibition gave me that moved me most. I felt a pang in my chest looking at the images of the artists as young men at the beginning of their careers, unaware of the influence their work would one day wield. In the weeks that followed, I became fascinated by their legacy and untimely deaths. I wondered whether their deaths were what allowed them to be solidified as icons — figures that have come to represent a generation of artists and encapsulate a very specific time, energy, and place. It is profoundly surreal to witness a fictitious documentary about a man who died over thirty years ago play out in your unconscious mind. Yet it was not this that made the dream stick with me; it was the time it took place. Not the present day but instead the early noughties — critically, before the advent of social media and at the crest of the second wave of neoliberalism. This is something I am beginning to think plays a part in the legacy of those artists who lived until today. If Haring and Basquiat had been one of them, would they have come to disappoint us with distasteful TikToks and outdated opinions?

When a gifted artist dies before their time, they are almost seamlessly inducted into mythology. The potential of what they could have created adds a sense of nostalgic grief to their deaths as we mourn the loss of what could have been. They become a template for us to project our own fantasies upon. The artist’s personal life and values become intensified as their image is distorted and readjusted by their death; the appeal somewhat altered by the added sense of tragedy. Social media has further extrapolated this mythologising due to the competitive nature of fandom and the attempted ventriloquising of an artist’s wishes and intentions. As fans, we contend with a hypothetical scenario in which we speculate on what an artist would make of their legacy. Yet here I am, adding my own speculative fantasy into the conjectural ring.

“Madonna’s current platform seems to present the tension of extending out of that time and naturally evolving into this new world — a world less concerned with the politics and cultural impact of an influencer and more with the very fact they wield influence.”

This year marks the 65th birthday of Haring’s friend and peer of the 1980s New York art scene, Madonna. Search on almost all major social media platforms, and you’ll find Madonna’s account packed full of selfies, dance videos, and intimate posts regarding her health, family, and friends. I find most of the discourse concerning her social media presence bears the mark of sexism, with people seemingly uncomfortable with an older woman’s sexuality. She does, however, provide a possible starting point for imagining what her peers might be posting. So much of Madonna’s current music and social media presence aims to commodify her status as an icon, with her songs and TikToks bearing constant reference to her name and influence. It appears as though, in her need to consolidate her legendary status, she feels she has to stay as close to the icon she was then, thus leading her to appear as an approximation of her former self. Her face eerily unchanged, and her music so wrapped up in a consolidation of iconism that it fails to represent anything as meaningful or influential as the work that made her. Haring, Basquiat, and Madonna existed within a very specific bubble of space and time, a time when celebrity was enmeshed with art and names were made on the dancefloor of Studio 54. Madonna’s current platform seems to present the tension of extending out of that time and naturally evolving into this new world — a world less concerned with the politics and cultural impact of an influencer and more with the very fact they wield influence.

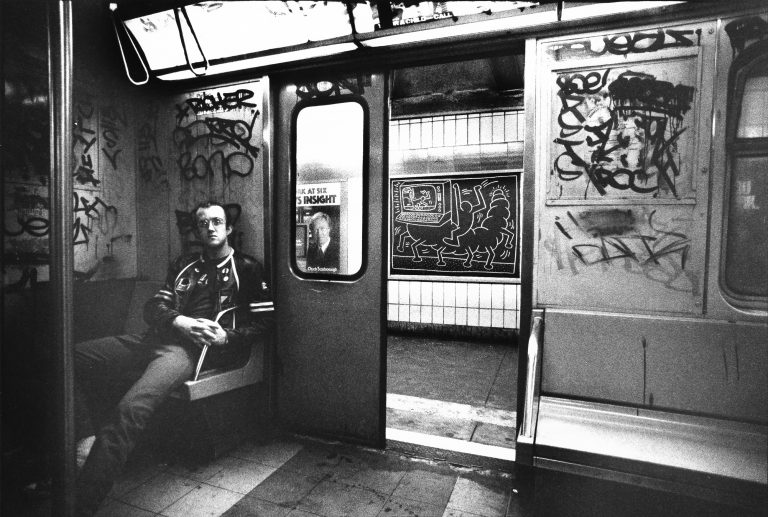

It is, however, another of Haring’s peers that I believe offers the best comparison. Credited with ‘creating’ the Instagram culture along with Andy Warhol, photographer Nan Goldin set up an Instagram account in 2017. Although resistant at first, Goldin now uses her platform to post both her new and old work. Her work has always encapsulated the blurring of private and public that, in some ways, most aptly embodies the Instagram experience. Beyond her photographs, she also uses it to promote her activism and astonishing work in taking down the Sackler family’s names from notable galleries across the world. Haring’s work spoke to his identity as an openly gay man and to key social issues of the time: nuclear disarmament, apartheid, drug abuse, and the AIDS epidemic. These were highlighted not only in his large-scale works, such as ‘Ignorance = Fear’, but in several informative posters that aimed to educate the public and support those affected. As time moves on, precarity still defines our existence, and many of the issues faced by Haring in the 1980s still breathe today. While there is no way to predict whether Haring would have, in fact, been using social media to dance along with Madonna to ‘Savage’, his work, despite its playful vivacity and humour, was always inherently political. I can’t help but picture him arm in arm with Goldin, promoting work that speaks wholeheartedly to the injustices he and his community were and continue to be faced with, using a social media profile like a blank wall on a subway platform as a space to demand livable lives.

The tense relationship between stardom and technology isn’t new; in fact, Haring was contending with it during his career. He was primarily occupied with creating art for the public and actively encouraged responses to his work. This exchange could easily be translated to the online public platform of today: a New York subway wall for a Facebook wall or Instagram feed. Yet Haring shared an acute anxiety, in both his art and his diaries, about the power of technology and its potential for misuse. Haring was distinctly aware of how the computer could play into the wrong hands, writing in 1984 of the potential for ‘misuse by those in power who only wish to control. The mentality of people who are motivated by profits at the expense of human needs’. 1 Not only this, but he almost eerily predicted in 1978 a ‘fight against a machine aesthetic’ 2 that echoes our present concerns over AI-generated images and art.

“Fame was always temporal, but it is unsettling to see an artist live on more as a brand than as a person.”

Perhaps fame has always been a fungible form of currency. Now, online, likes are our currency. Through social media, fame becomes readily commodifiable, with any form of notoriety online ready to be exchanged with brands for money. While social media platforms do make arguments and opinions less one-sided than they were in the 1980s, in this new territory, anyone and everyone can have fans and enemies. Ironically, though, much of Haring’s enduring legacy is due to the proliferation of his images online. One need only visit any major fashion brand’s Instagram page to be met with Haring’s artwork plastered onto t-shirts, shoes, makeup cases, or tote bags. The digital sphere is what enables his iconic images to resonate with contemporary audiences. But is this how we measure an artist’s impact — their capital footprint? While it is encouraging to see a younger generation engaging with the work of Haring or Basquiat, it seems at odds with the two artists’ digital anxieties and attitudes towards posterity. Haring had a message — a unique blend of political activism and a commercial desire to make art for the masses. While many of these collaborations are in line with Haring’s desire for affordable art, and these collaborations are what enable his foundation to distribute grants, does Primark really care about his message? A quick look on their website will find him simply described as an ‘iconic American artist’ with no mention of his work as an HIV activist or his ethos, the very thing that allows companies access to his art. Fame was always temporal, but it is unsettling to see an artist live on more as a brand than as a person.

Much like my dream, this article is a fantasy. It is an imagining of what might have been, fueled by my own sense of loss — the great tragedy that a great artist didn’t live longer. A mourning for all that he might have created or not created, tweeted or not tweeted, streamed or not streamed. Whatever my own attitudes towards technology and my speculation of what Haring may have made of our new technological world, I would rather Haring were alive to make those decisions – and possibly even cringey TikToks – for himself. It is impossible to know, as it is the fact that hedied that allows him to remain untouched for me. Frozen in time and place, in a photograph from a subway car with his work framed between the doors as they’re about to close. Or in the fragments of a dream, still radiant and youthful, recounting wild tales and speculating on what’s to come with Einaudi playing somewhere in the distance. Eyes closed in the back of a car in the early noughties, fading away from a future he’ll never see.

Words by Lucy Carless