Al Freeman’s French bulldog puppy, Moe, is chewing on one of the pieces from a body of work she is creating for an upcoming show at Los Angeles gallery Grice Bench. So far, so cute—until I realise that Moe is taking a flaccid pleather penis to task. Known for her soft, large-scale sculptures of everyday objects, the New York-based artist is taking an autobiographical turn with a new series of boyfriend pillows that are based on her own ex-boyfriends as well as her friends’ exes. “They are all wearing tops but no bottoms. Shirt-cocking,” she tells me. “It’s a show of portraits of people that my friends and I have known.”

It was a body of work she had been wanting to make for a long time. “I felt overwhelmed at first,” she notes. “Originally I was going to do only my own exes but revisiting those narratives through the work became emotionally exhausting. I decided to include other people’s exes, giving myself an emotional break by working on multiple pieces at once.” Curiously, Freeman’s former partners began reaching out to her after years, as though they had been cosmically summoned by the physical manifestation of her boyfriend pillows. “I’m not usually a believer in witchy things but this has been very strange,” she adds.

A Yale graduate, the Toronto-born artist is represented by New York gallery 56 Henry, where she had her first solo show in 2017. She has featured in exhibitions with Aroras, São Paulo; Carl Kostyál, London and Stockholm; Sorry We’re Closed, Brussels; and Bortolami Gallery, New York, among others. Freeman is the doyenne of deadpan: her stuffed replicas of male-coded commodities echoes the absurdity of our gendered hierarchy.

“The objects started out as sculptures of the debris that appeared in photos I was searching for online”

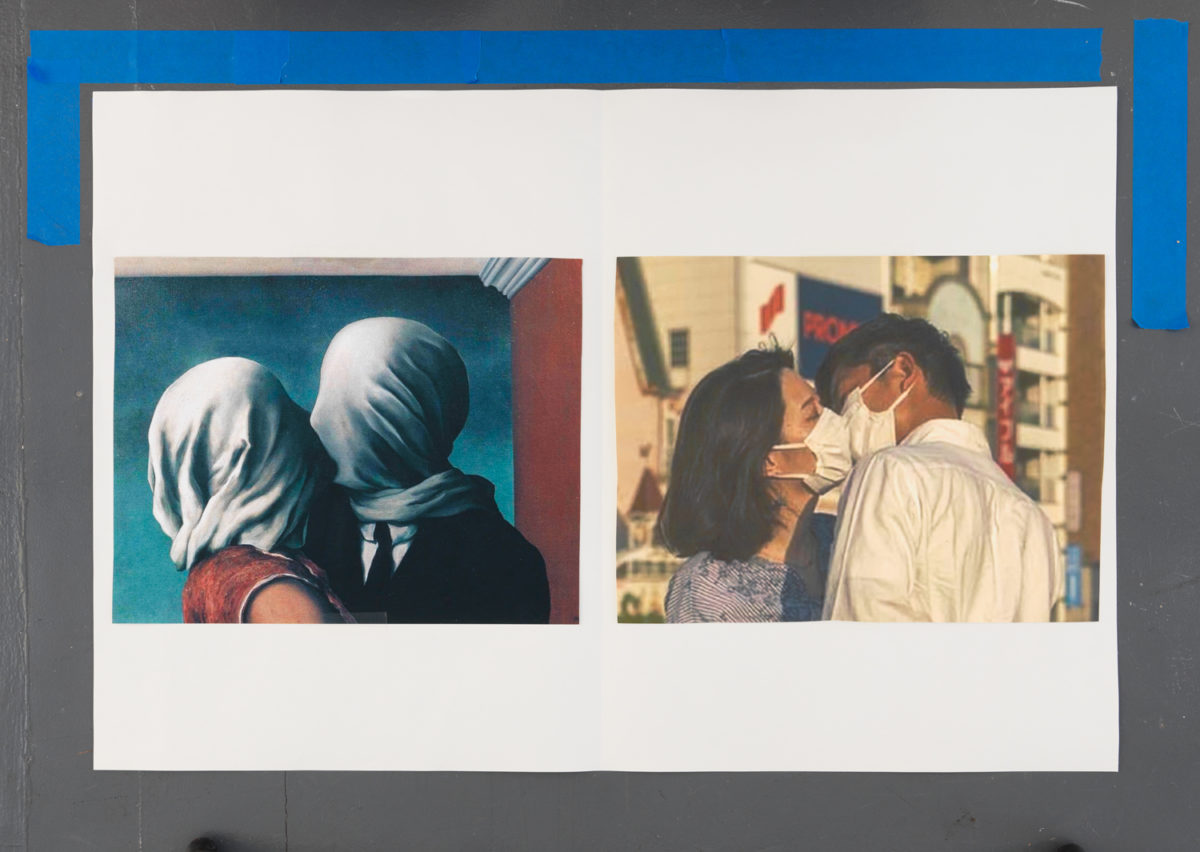

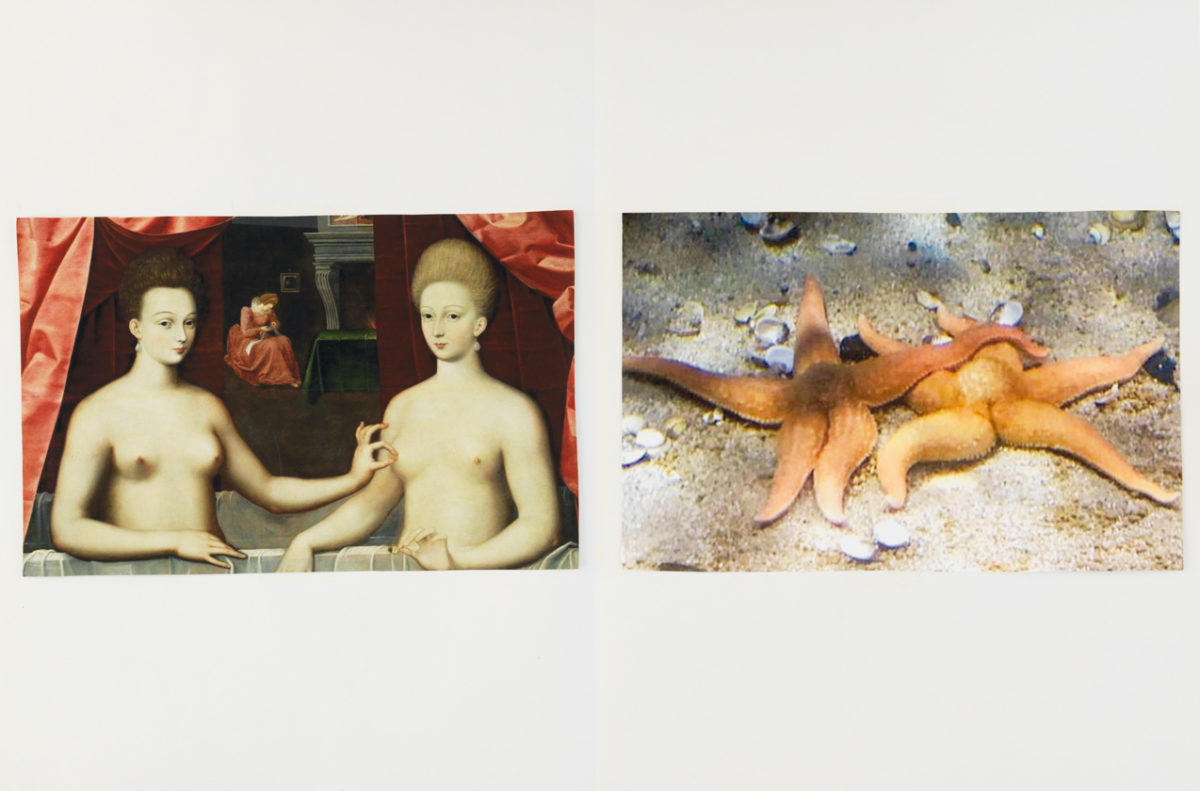

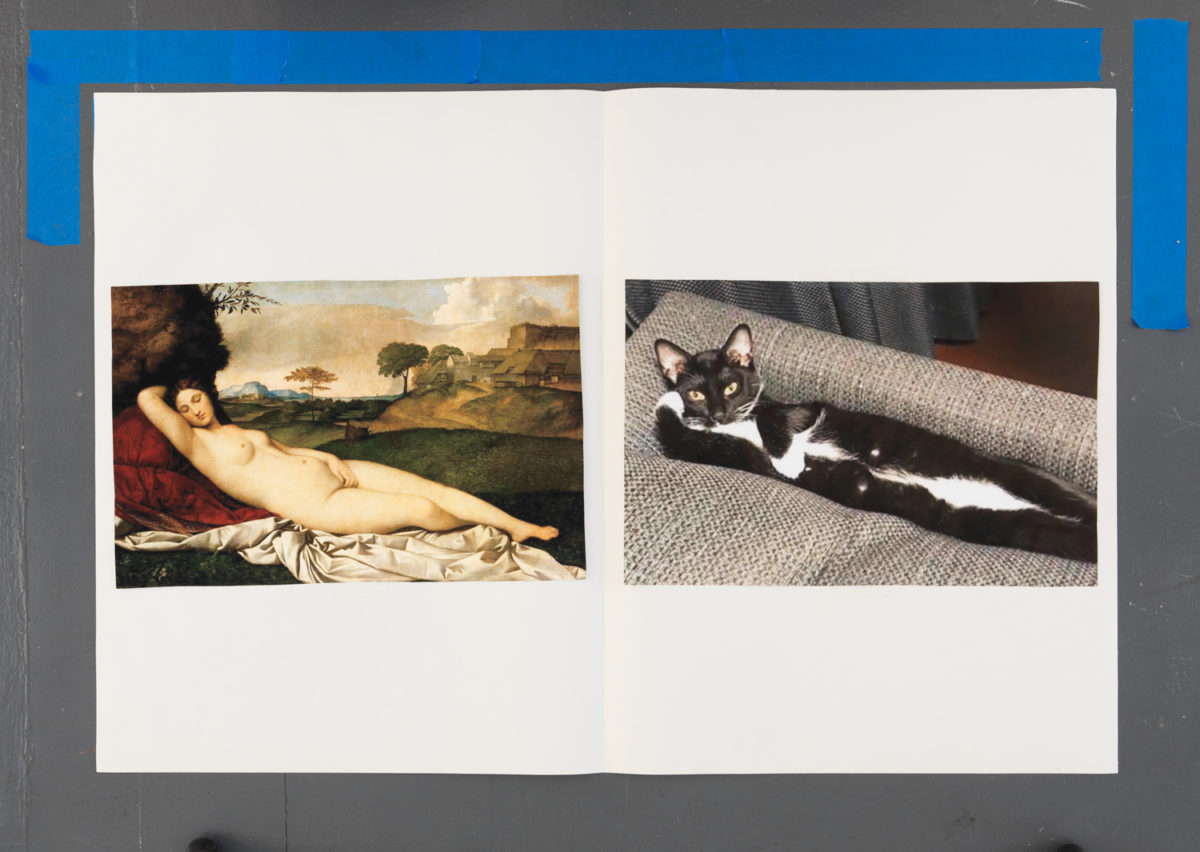

Similarly in the series Comparisons, Freeman riffs on art history, pitting famous works against images mined from the Internet. In one, she threads starfish with the French painting of Gabrielle d’Estrées pinching the nipple of (presumably, argue historians) her sister, the Duchess de Villars; in another, Magritte’s surrealist painting of two veiled lovers is paired with a couple sharing a kiss through face masks.

Freeman has immortalised everything from cigarettes and extensions cords to energy drinks and lasers discs as polyester-filled sculptures. “The objects started out as sculptures of the debris that appeared in photos I was searching for online, images of guys passed out at frat parties and amateur gay wrestling porn,” explains the artist of her process. “Many of those images ended up in my Comparisons pieces. The objects I chose are informed by those photographs and the culture they represent.” Her sculptures are witty and pointed, but never preachy. Asked about her relationship with humour, she replies simply: “It’s how I meet the world.”

“Every piece is different. I don’t know how to make the sculptures until I actually do it”

The artist approaches her process intuitively: “Once I decide on what I’m going to make, I look at images of that thing for reference. I identify the different parts of it, and think of how to make and fit the various shapes together,” she adds. “I’ve never made a pattern—I eyeball and draw directly onto the vinyl. What keeps me interested is that every piece is different. I don’t know how to make the sculptures until I actually do it.”

For the boyfriend pillows, Freeman has been working largely from memory. “I was worried that the human form wouldn’t translate so I started with something familiar and made a bunch of dicks,” she quips. “Then I started experimenting with the rest of the body, and figuring out how to make their clothes from wool stadium blankets. There was definitely an element of trial and error.” The bodies are made from pleather, the hair from faux fur or shearling, while the clothes have been stitched together from the blankets.

During an organisational spree of drawings in her studio, she ended up rediscovering her American Rapist series from years ago. “The drawings predate all the soft sculptures but featured faceless lumpy figures wearing shirts with no pants,” says Freeman. “Essentially they looked like studies for what I’m currently making so I decided to let them inform the sculptures more and now use them as references. Ideas always circle back on themselves.”

There’s a conflicted attitude towards traditional gender roles that plays out in the artist’s work, which centres on masculine tropes. “Even as a cis-hetero woman, I’ve never identified with conventions of femininity. A friend once called me a gay man trapped in a lesbian’s body, which I didn’t fully understand but somehow felt accurate,” reflects Freeman. “There’s an element of reversing the male gaze—but that alone also feels too simplistic as an explanation. Whether masculinity or hyper-masculinity is in the work, this is purely some element of my personality and worldview coming through.”

“Even as a cis-hetero woman, I’ve never identified with conventions of femininity”

Freeman usually gets into her Brooklyn studio in Bed-Stuy at around noon, working nonstop until 8 or 9pm while listening to podcasts or music (and playing fetch with Moe, when he demands it). Aside from Moe, the artist shares her space on occasion with her “helper”—an LSE student, historian and writer who got stranded in the city because of the pandemic and never left. “If he’s there working or hanging out it adds another dimension to the day. His brain operates in a totally different but complementary way to mine so we always have a lively conversation about art, mutual friends, politics.”

In September, Freeman will have her first UK solo exhibition at Carl Kostyál’s London gallery. The Grice Bench exhibition is set to open in June. A typical evening at the studio by now includes winding down, playing Harold Budd, ordering food in, and drinking bad wine from the liquor store downstairs. “I love the time of the day when the studio transforms from a workplace to chill night loft vibes,” Freeman says. “The neighbourhood is very busy and the elevated JMZ train passes right by my front windows every few minutes. Outside is an iconic New York cityscape and inside there’s a warm, creative dynamic energy. It’s by far the best studio situation I’ve ever had.”