Following the closure of her residency exhibition ‘Figure This II’, the gallerist talks the value that springs from taking risks, the importance of nurturing intercontinental creative dialogues, and why “opening up” the gallery space as a community-building platform is the way forward

A disruptive force in the contemporary art scene, British-born Polish entrepreneur Sarah Kravitz is the mind behind Sarah Kravitz Gallery – an independent platform spotlighting rising and mid-career artists from underrepresented backgrounds. Established in Warsaw in 2015 and since 2018 located steps away from the hustle and bustle of London’s Soho Square, the gallery leverages art and its manifold manifestations as a means of connecting with a wide, multigenerational audience. Now with a roster of international, cross-media talents under her belt – including Korean Venezuelan visual artist Suwon Coromoto Lee, Ethiopian-born self-taught creative Nahom Teklehaimanot and Polish painter Edna Baud – Kravitz proceeds on her mission to diversify the art landscape through showcases that celebrate her chosen trailblazers and educational initiatives aimed at making the gallery space accessible to everyone, demystifying it from the inside.

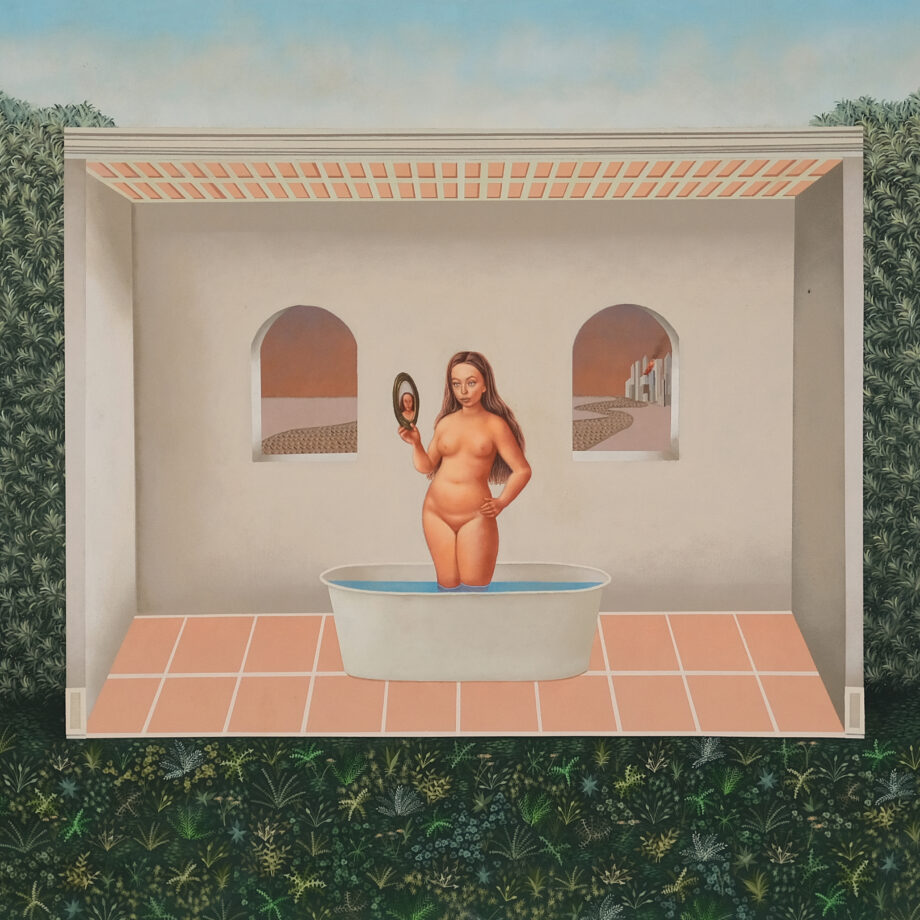

The fruit of Sarah Kravitz Gallery’s latest artist residency, Figure This, a recent highlight of its theme-led exhibition programme, saw the young gallerist come together with Ghanaian artist, curator and philanthropist Joseph Awuah-Darko in a symbolic artistic encounter between Central and Eastern Europe and Western Africa. First inaugurated in Soho last autumn (11 October–4 November) as part of Frieze week, an expanded iteration of the group show travelled to Rye’s Bridge Point Studios between 25 November and 10 January, where the residency took place. Holding up a mirror to the complex dynamics that shape the course of our time, Figure This presented viewers with a collection of paintings grappling with identity, migration, womanhood, the body and the Black experience.

Selected by Kravitz and Awuah-Darko in collaboration with the Kowitz family, who supported the project, the artists at the heart of the exhibition turned to figurative painting as an extension of their subjective being. Brilliantly woven together by curator Elaine ML Tam, the artworks on display offered a window into the gallerist’s unifying view of art – its power to defy boundaries. Set to embark on a global venture that will take her to Poland, France, the UAE and Asia in the coming months, where she will unveil a series of pop-up exhibitions, Kravitz talked to us about her plans for the future against the art nouveau, sophisticated backdrop of Old Compton Street’s jazzy Cafe Boheme. A gloomy December afternoon instantly turned better.

Sarah Kravitz: I have been following Joseph Awuah-Darko’s Noldor Artist Residency for a long time. They have this wicked, Brutalist architecture space, the Institute Museum of Ghana, which hosts the most cutting-edge contemporary African art programme I have ever seen: it is the first independent artist residency for contemporary African artists across the continent and the diaspora. I asked him to join forces on a project focusing on Western African and Central as well as Eastern European art and he was instantly up for it. There has never been any creative exchange between these geographical areas before. Considering the state of today’s migration from sub-Saharan Africa across Europe, it is a conversation that needed to happen. Besides being an interesting dialogue from an artistic point of view, it was also an opportunity to establish a relationship between the regions. Working with Joseph enabled me to realise how much our experiences align; our parents share the same (mis)understanding of art. Art has never been at the forefront of culture in Poland, where I come from. This partnership coincided with the surfacing of a new chapter in my practice: this year Joseph and I will be holding the first exhibition of African artists in Poland – an important first.

Gilda Bruno: How will this forthcoming show feed into Poland’s current political climate?

SK: Poland has been under right-wing rule for the last eight years: abortion was made illegal again and a lot of progressive laws were scrapped. It was a massive step back. Now they have a new coalition government which is hopefully going to facilitate the development of this project. I can see Poland changing – it is an ideal time to lay the foundations for a more diverse Polish arts scene. It is not just about finding ways of supporting underrepresented artists, though, but also about connecting with a new wave of collectors, leveraging the strong economic growth of the last few years. On the one hand, you have the social turmoil, a fertile, breeding ground for artists to express themselves, which unveils their own beautiful worlds. On the other, an economy that has been growing steadily for the last two decades, leading to the rise of a new type of collector.

This emerging scene brought about a whole new art market. Compared to the UK, where the sales are conditioned by a lot of factors, the Polish market is pretty much filterless: its young collectors walk into galleries exclusively trying to get a sense of what a given artist stands for, what they are striving to communicate. Although they go in with an open mind, they are the opposite of naïve. They speak to gallerists and are very respectful when it comes to this dialogue – it is a win-win kind of situation for everybody. Because different collectors are genuinely interested in different artists, the galleries are not competing with each other. Instead, everybody – whether artists, gallerists or collectors – are helping each other out, moving towards the same goals.

GB: What gap are these artists, galleries and collectors attempting to sew within the contemporary creative scene? What is currently missing?

SK: Women are dominating the art market in Poland right now – it has become a site for female independence. As a Polish woman, you are taught to be submissive; the less you say, the better. One of my favourite artworks from Figure This II is Helena Stiasny’s Exemplary Student (2021), which is titled after the tagline featured on a badge worn by the young girl captured in it. It borrows from an image of her mother as a school kid in the 1980s. The idea is that, for you to be seen as “exemplary”, you need to be obedient and quiet. I am part of the first generation of Polish women actively fighting against that, seeking equality, taking up space in the art community and using it to free themselves from decades of oppression. Women artists in Poland are finally being represented. Although institutions are still quite censored – and have been particularly so under the former government – they have managed to climb to the top of the Polish art world thanks to private collectors who are buying their work and giving them the opportunity to make art for a living.

GB: It is a shift that starts with the people.

SK: Precisely. And it is quite a political one, too, as the Polish status quo, the institutions, are not in favour of what the community wants. It makes these female artists even more relevant. Discrimination towards women is an issue that still exists in many cultures; Polish art is underscoring the urge to take action against it. My 11-year-old daughter will probably have to engage in the same conversation. If there is something that struck me about the talents featured in Figure This II, it is how young most of them are – they are all under the age of 26. I first began developing my own research on Central and Eastern European art when I was a student at Goldsmiths. I started out running club nights in Warsaw which loads of young artists would attend. Getting to know those creatives was a new beginning: none of them had ever been represented in London before, but my body sensed there was something going on there – their talent. I am grateful to be part of this Polish renaissance.

GB: To run an artist residency inspired by the encounter between Central and Eastern European and African art must be a unique opportunity to tap into your own culture. How does this initiative allow you to straddle the continuum between your Polish roots and your British identity?

SK: Part of the residency’s focus is on rebranding what it means to be Eastern European: Eastern Europeans are mostly associated with hard-working labourers – our creative potential has been overshadowed by that reputation for a long time. Art has the power to, essentially, redefine how a nation is represented and perceived. When I was a kid, I didn’t want to be Polish. In school, I always felt like a second-class citizen, so I am excited to pave the way for a more nuanced representation of our identity. I love championing artists who still haven’t got their opportunity to be represented and recognised more widely but I also need to ensure that collectors become interested in them – that is where the real challenge comes in. Yet, doing it within a young, thriving art market like Poland’s makes things more engaging. Besides the projects I am working towards alongside African artists, this year I will also be representing some British Royal College of Art graduates in Poland.

GB: What criteria served as a frame of reference when selecting the talents to spotlight in the second instalment of Figure This?

SK: It was an intuitive process. We wanted to balance some more well-known artists with lesser-known names to obtain a selection that felt rounded. You have people like Annan Affotey who are already recognised within the arts community, or Preslav Kostov, a Bulgarian-born, London-based RCA graduate, but also others who are just starting out. Another artist part of the exhibition, Aniela Preston, was born in the UK from a Polish mother, just like me. I knew I wanted to find a way of fusing the artists’ heritage and different backgrounds into the show. Elaine ML Tam, who curated it, did a fantastic job at making everything look cohesive.

GB: The showcase took a fresh look at the figurative painting tradition, re-envisioning it for the contemporary eye. What is these artists’ contribution to the history of the medium?

SK: Identity is certainly the leitmotif linking them all together. Some of them grapple with womanhood and what a woman represents, a key theme of Aniela Preston’s production. Others – like Annan Affotey and Nahom Teklehaimanot – offer viewers a bold, intimate portrayal of the Black experience, tapping into the representation of Black identity and the politics surrounding it. Preslav Kostov’s haunting work explores migration through the presence of multiple, interlaced figures, while Julia Kowalska scrutinises the antithesis between the physicality of the body and the ephemerality of emotion. It is less about how their aesthetic revolutionises figurative painting and more about the context in which their canvases emerge; what they are trying to say to us.

GB: Figure This II was realised in collaboration with the Kowitz family. How did this partnership come about?

SK: The Kowitz family has run multiple residencies in that space before; they have invited various galleries and last year it was my turn. It was an eye-opening experience: 2023 has given Sarah Kravitz Gallery a greater sense of purpose. I have spent years doing pop-up exhibitions, trying to understand what people want when it comes to art. This residency showed me what it is that I am aiming for, and it was a very organic discovery. Sometimes you make a decision before even understanding why you are doing it, before being able to process it. The next step will be taking these artists and their craft to countries they have never exhibited in before.

GB: Within the art world, the spotlight is mostly on artists themselves; gallerists rarely get to discuss what it took them to get where they are today. What would you say to those keen to break into this field?

SK: Unlike the mentorships, residency programmes, open calls and grants available to artists, there isn’t much support for gallerists out there. We need to think about specific art professionals as a segment of a larger industry: we all contribute to it in complementary ways. I would love to become a mentor for aspiring gallerists. For now, I can say that it is crucial to hone in on your interests – to specialise in something. If before you could get away with experimenting across genres and mediums, today you need to mark your own territory. In emerging markets like Poland, gallerists and artists both play a vital part within the art game. People come to London from all over the globe, making it one of the most influential cities in the world. I am lucky to have a gallery in Soho Square where open-minded people can learn more about the talents I represent. Still, the UK art industry has set hierarchies and rules; it is very tight-knit and developed. For years, this kept me from demanding real change. Now I know that taking risks is what the art world benefits from in the long run. With my projects, I want to make it bigger.~

GB: What principles guide your generation of gallerists?

SK: We have certainly moved on from the “white cube” conception of a gallery. We are also more aware of the need for collaboration; exclusivity between an artist and the platform representing them doesn’t really exist as it used to in the past. Instead, we value cooperation over competition and serve as a bridge between talents and collectors.

GB: What do you look for in an artist?

SK: Work that feels consistent – to me, that is the most important element. Somebody who understands what they are doing with their work. Still, some things can’t be pinned down: to be an art dealer, you need a good instinct. Sometimes you can’t explain why a given artist feels right to you, as art takes on so many different forms. Ultimately, it is all about a feeling. Joseph and I will continue our programme, the next step of our collaboration being an African artist group show in Poland this spring. We are also planning on working a lot more with art film directors in the future: we have already teamed up with some Ghanaian filmmakers for our first short film screening, Films About Ghana, some of whom were nominated for Tribeca Festival. Film will definitely become a more prominent aspect of my gallery programme, too.

Just like I advocate for a shift in the way gallerists communicate with artists and one another, I believe the gallery space needs to evolve, too: it can no longer be one-dimensional or static. There should be more education tailored to young kids. I organise activities for children to make the gallery accessible to everyone, flattening the entry barriers that prevent people from making the most out of it. Loads of incredible galleries are not thinking about the bigger picture: opening up the space to the wider public allows me to reach more collectors and nurture a sense of community. The goal is to diversify the gallery through a more inclusive variety of arts and educational programmes.

GB: Galleries and museums should be a place where people can gather without feeling inadequate.

SK: Exactly, but there is no point in eradicating the more traditionally led galleries housing artworks worth millions of pounds: when it comes to art, there is no such thing as a one-size-fits-all approach. We all know that the money going into the industry is what allows art to stand the test of time. Personally, I feel the responsibility to rethink what the gallery space embodies in today’s society, how we can keep it fresh and relevant. It is great to see collectors that, up until recently, would have never dreamt of going to a commercial art gallery becoming genuinely curious about my vision and artists; to interact with passers-by walking into it without feeling out of place. The art scene wouldn’t exist without people.

Written by Gilda Bruno