Under the Influence invites artists to discuss a work that has had a profound impact on their practice. In this edition, artist Ian Cheng looks at the way that the work of psychiatrist Eric Berne changed the way that he thought about human personality when it came to creating the AI simulations that people his work

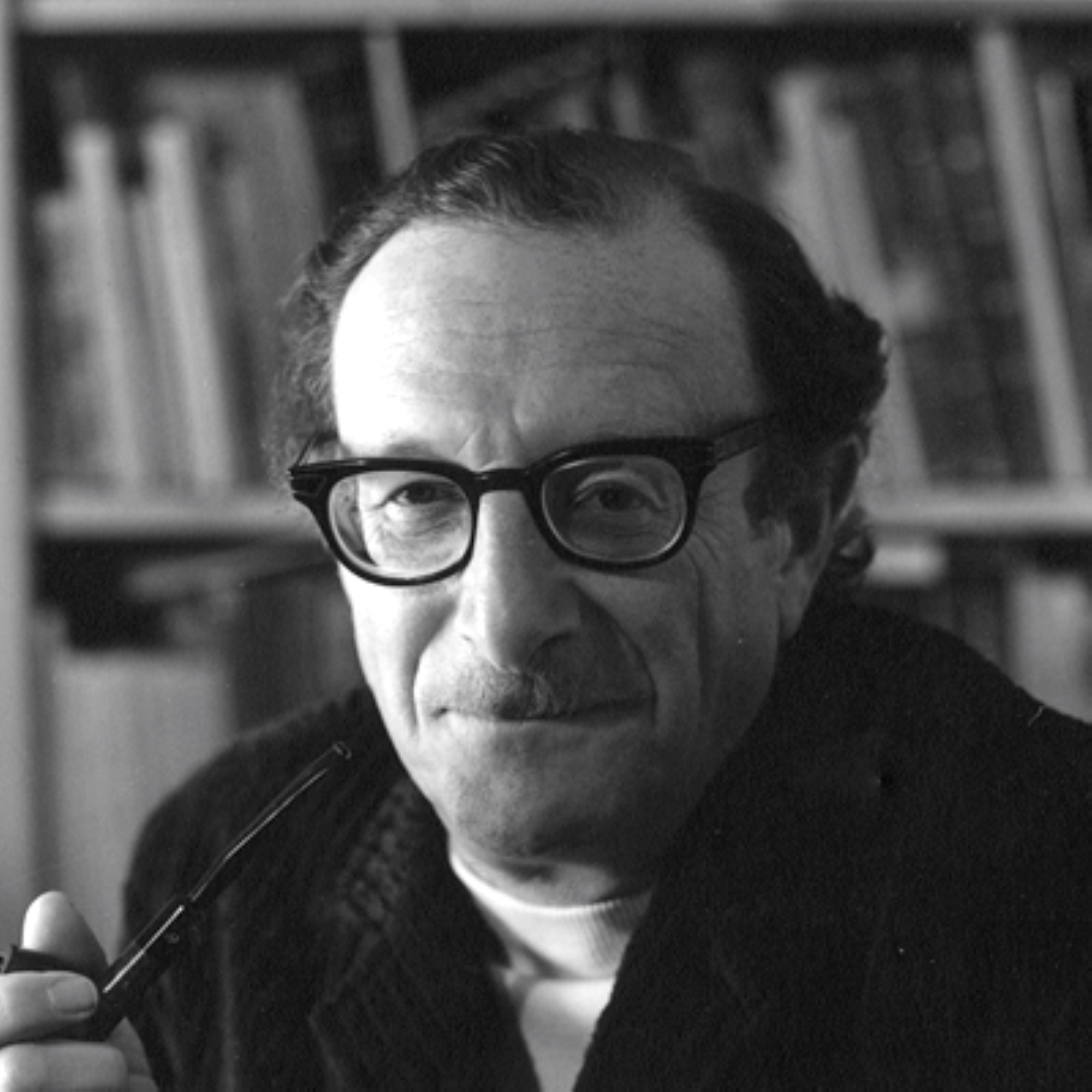

I discovered Eric Berne when I was working on Bag of Beliefs (BOB), which is an AI creature, an artificial lifeform. Berne had a previous book called Games People Play (1964), which is about the scripts that people follow as a way of passing the time before they die. It’s a structured way of socialising that we all implicitly do.

Through his many thousands of psychiatric patients, Berne discovered that sometimes he wasn’t talking to a coherent person. He was talking to a child inside of them, and sometimes to an automated parent inside of them. He thought, “This is quite similar to Freud’s ideas of the id, superego and the ego.” But in Freud, these concepts aren’t observable, they’re speculative. Berne’s work is all based on the observation of human behaviour.

From this he developed Transactional Analysis, which differs from psychoanalysis in that Berne didn’t believe that people present their true behaviour in front of a therapist. Instead, they perform for the therapist. His analysis of patients was often done in groups, so he could see how people acted with each other. Inevitably, a transaction occurred: the person’s parent, child or adult ego state emerges and takes control of the body.

“Berne didn’t believe that people present their true behaviour in front of a therapist. Instead, they perform for the therapist”

This idea of having different sub-personalities inside you was a big inspiration for making BOB. At the beginning, we had a naïve notion of being able to create a coherent AI model that produces animal-like behavioural diversity. But after reading Berne, his ideas of sub-personalities started to make sense in an engineering context. It’s a much easier way to approach complex behaviour computationally. On a psychological level, I also feel it’s closer to true human behaviour. So that’s the way I’ve approached more and more exhibitions, as software releases instead of thinking of the work as a closed and perfected thing. I think of it how you think about versioning software.

I’m convinced that the brain is engineered so that perception is purposefully limited by motivations. If you’re really hungry, it limits your perception. You start to only see food and the obstacles to getting food. Everything else becomes irrelevant. It’s the same with LSD. In my experience, the purpose of psychedelic drugs is to make everything in the world overly relevant, so you can’t parse it. That’s why it’s so fun and interesting. A perceptual filter is removed, so a leaf or crack in the ground becomes fascinating.

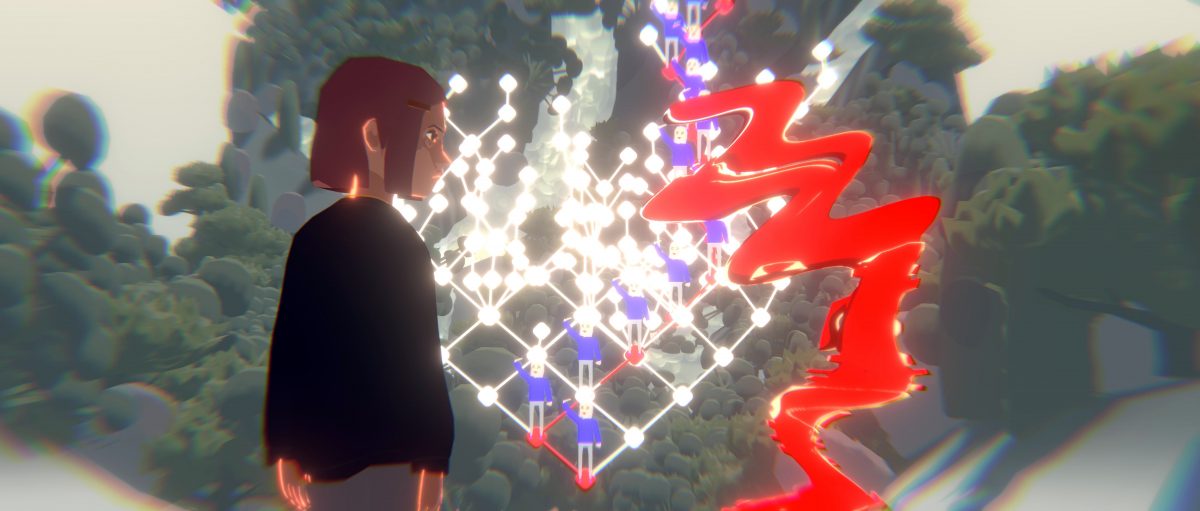

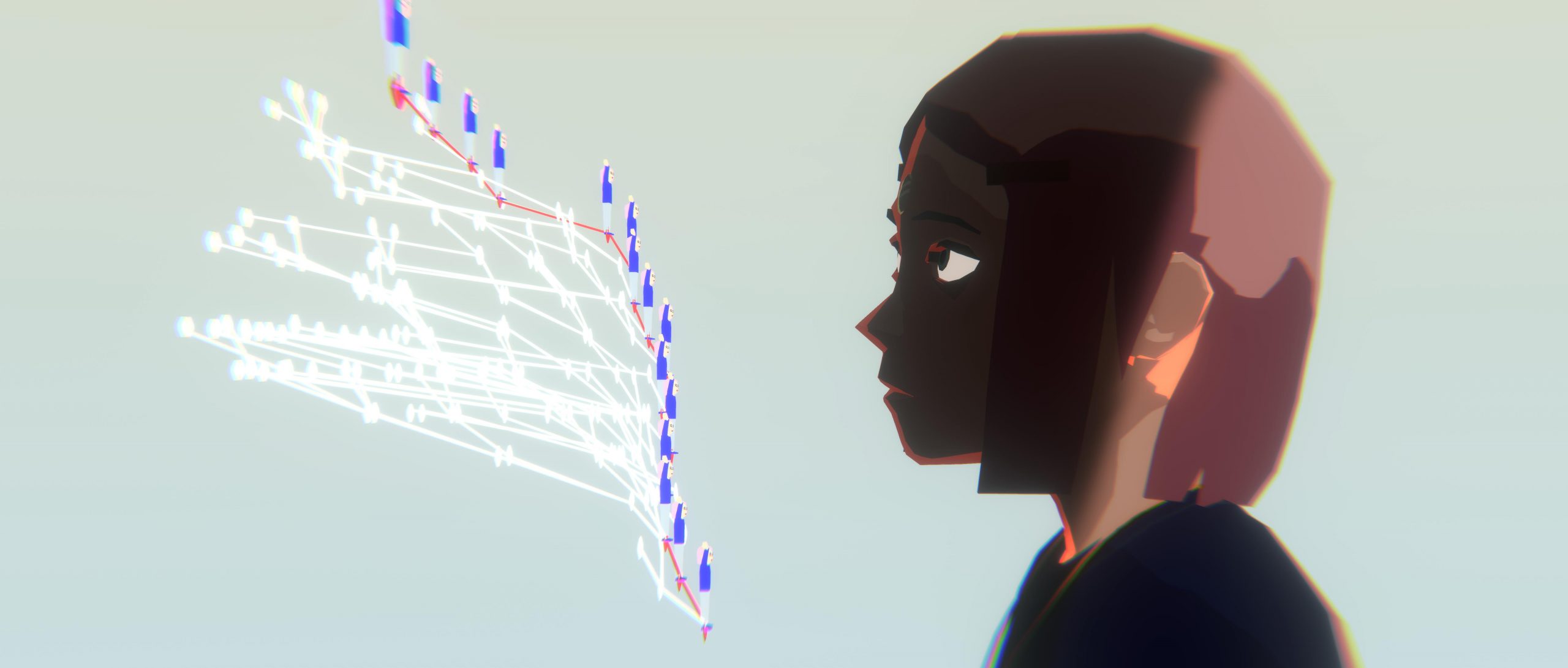

My current project at Halle am Berghain, Life After BOB, is a narrative film that includes a much more advanced, speculative character of BOB. Here it’s an AI creature in your mind, an inner therapist or life coach. The work draws heavily from Berne’s central thesis in What Do You Say After You Say Hello, which is premised on the fact that it is impossible for people to project their futures, because life is so expansive and difficult to organise.

He theorised that people unconsciously organise their lives according to life scripts, especially when they’re children. A simple version could be a fairy tale. Or simple ways that you envisage stages of your life. “Do I imagine dying surrounded by friends, or dying alone?“ ”Do I imagine myself going to college, or getting married?” These sound so normative, but these are the scripts of culture that all parents pass on, as a way for a person to abstractly organise the chapters in their life. Everything is abstract until you live it.

“Berne believed that everyone lives out a fairytale as a template script that they’ve cast themselves into with the help of their parents”

Obviously we take different paths, but Berne believed that everyone lives out a fairytale

as a template script that they’ve cast themselves into with the help of their parents. Most people aren’t satisfied with the script that they’re unconsciously barreling down. It might be a mismatch: maybe your parents had old fashioned values; maybe the culture you grew up in radically shifted in your teens, which alters the relevance of your life script.

“Berne put a high moral value on agency, while recognising how difficult it is to surface that agency”

Carl Jung was a big influence on Berne. He argued that everyone lives out a myth that they’re unconscious of. And you had better find out what the myth is, because maybe it’s a tragedy, and you might want to rewrite it. That’s at the heart of what Berne is trying to capture. He put a high moral value on agency, while recognising how difficult it is to surface that agency.

The work’s original, rather clumsy title was Life Scripts After AI, so that’s what I wanted to explore with Life After BOB. How do people organise themselves when you have AI organising how you’re raised, acting as a kind of co-parent?

As told to Ravi Ghosh

Ian Cheng, Life After BOB, is presented by LAS at Halle am Berghain, Berlin, until 6 November

Images: Ian Cheng, Life After BOB: The Chalice Study (still), 2021. Courtesy the artist

Under the Influence

Discover the connections between today’s creatives and the artists who helped shape their work

READ MORE