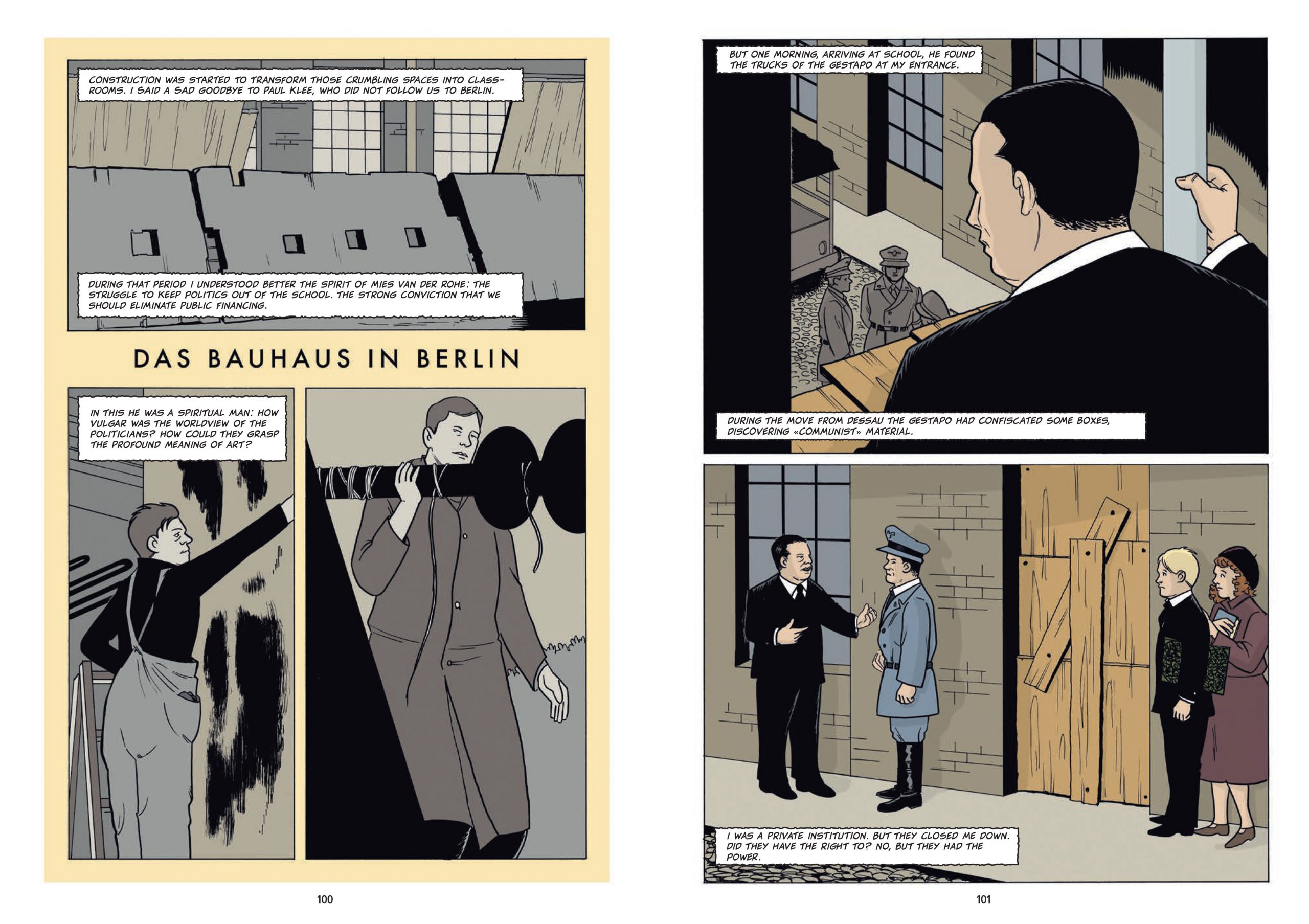

In the midst of the centenary celebrations of the Bauhaus in 2019, there was a strange even ghostly feeling of incompleteness. Part of this was due to an unavoidable sense of loss. Though it conquered the world of design, the school itself was only open for 14 years before it was closed by the Nazis, and its teachers and students scattered to the winds or murdered in the Holocaust.

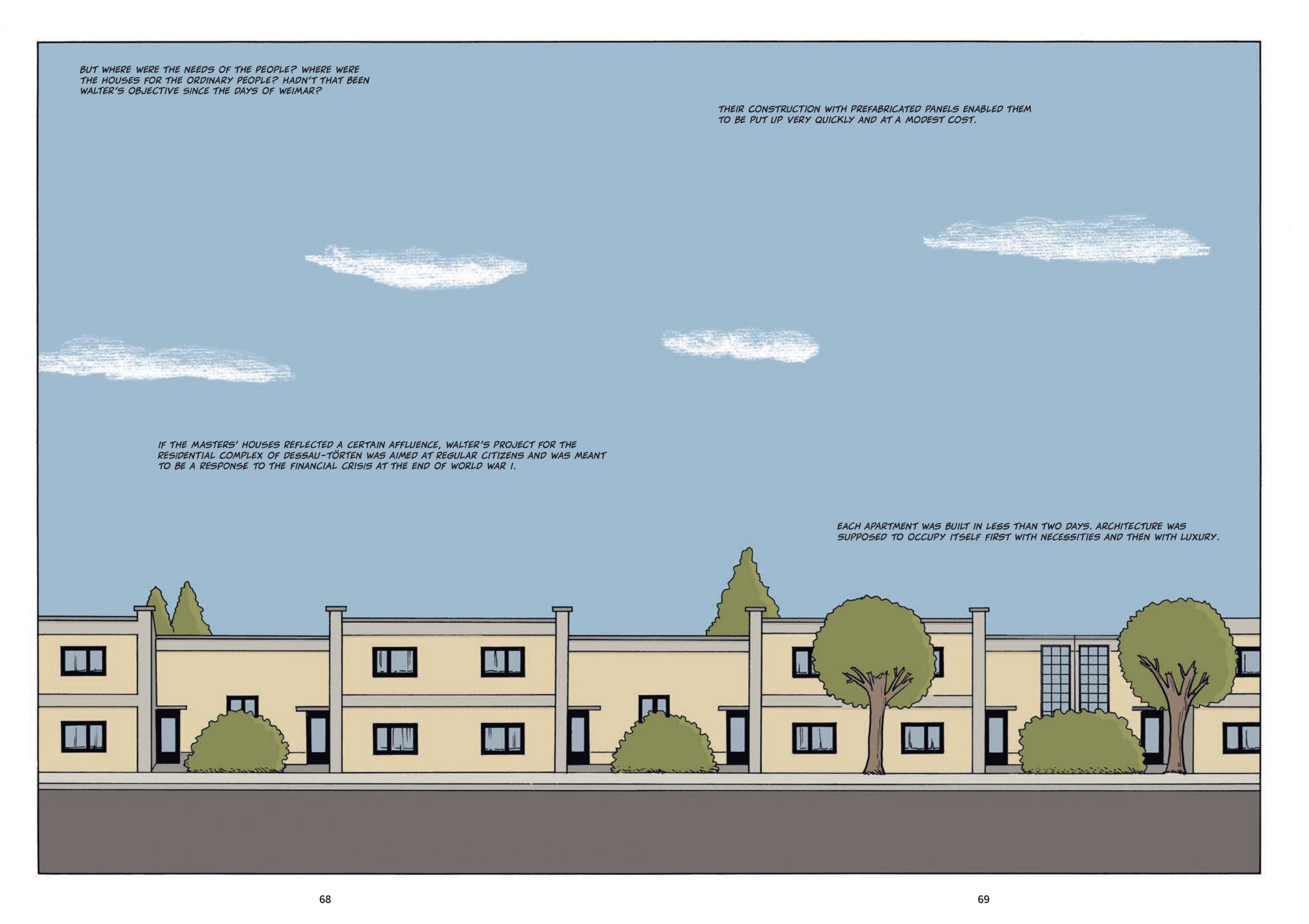

The iconic buildings survived in a kind of suspended animation, not quite relics but no longer part of a world-changing art school either. Though we could see the influence of the Bauhaus all around us, from our phones to our buildings, what exactly was being celebrated? A school? An aesthetic? A design sensibility? A period in time? A group of long-lost artists and designers? A spirit? The closer you try to get to defining what the Bauhaus was, the more elusive it seems to become.

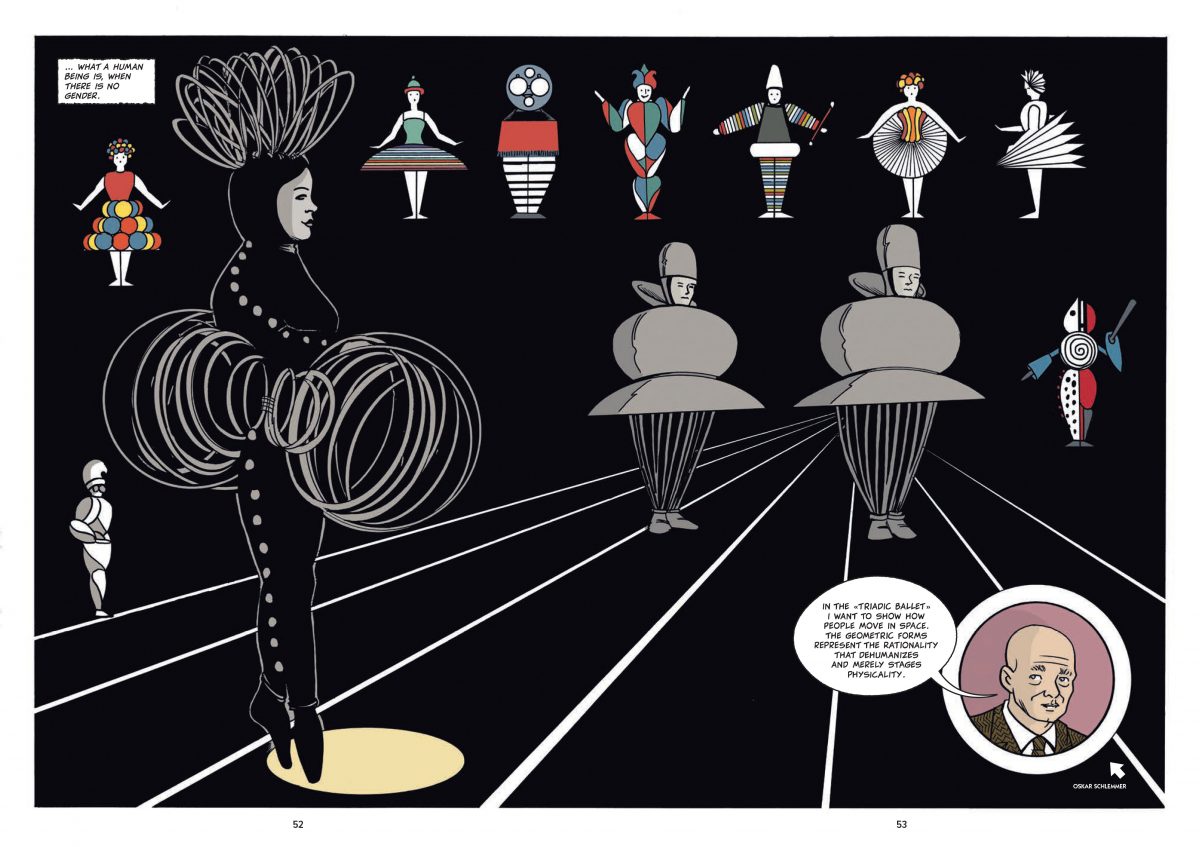

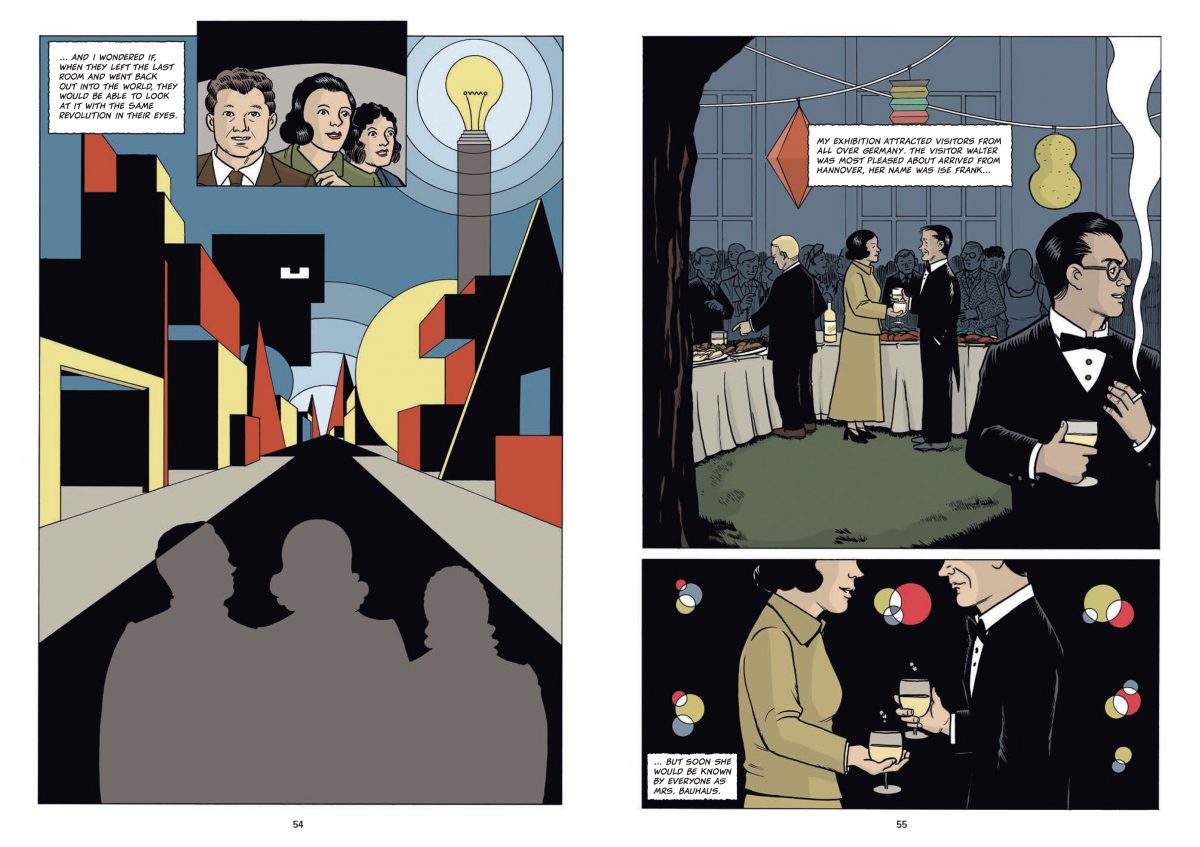

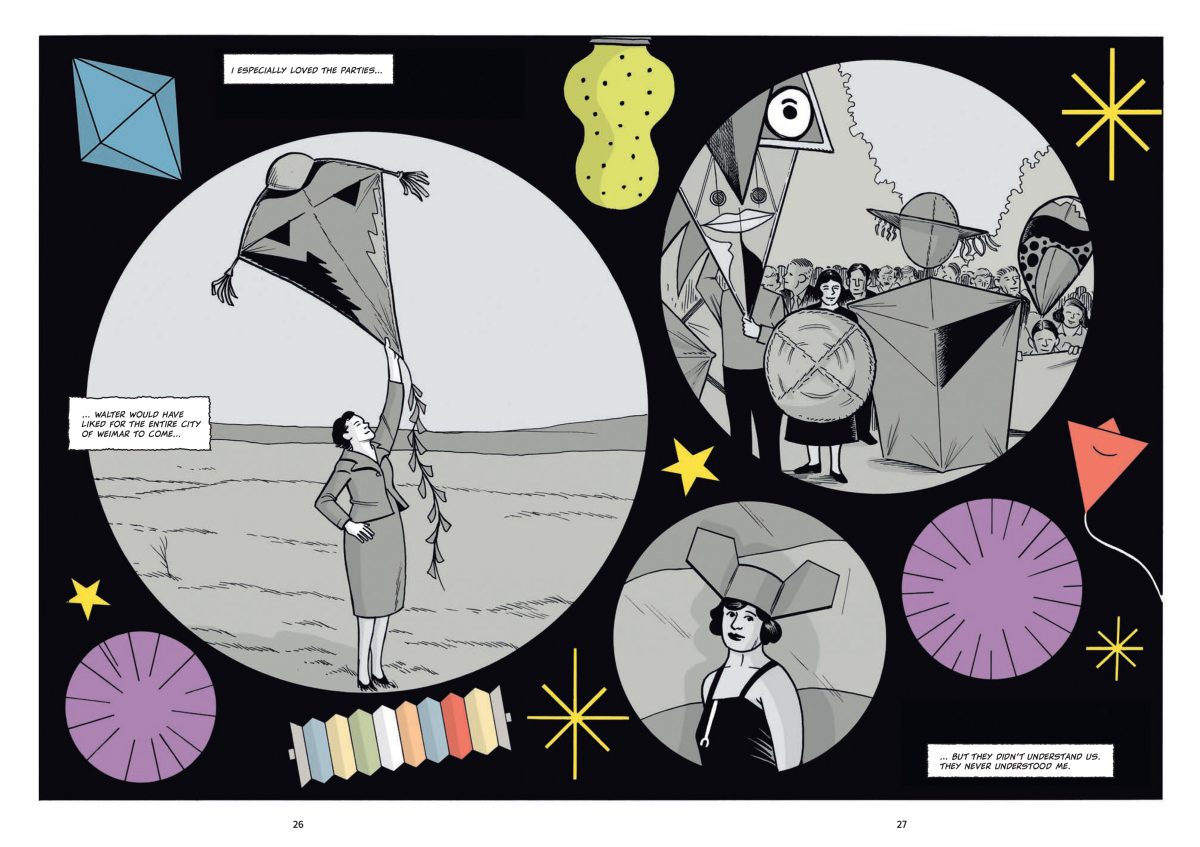

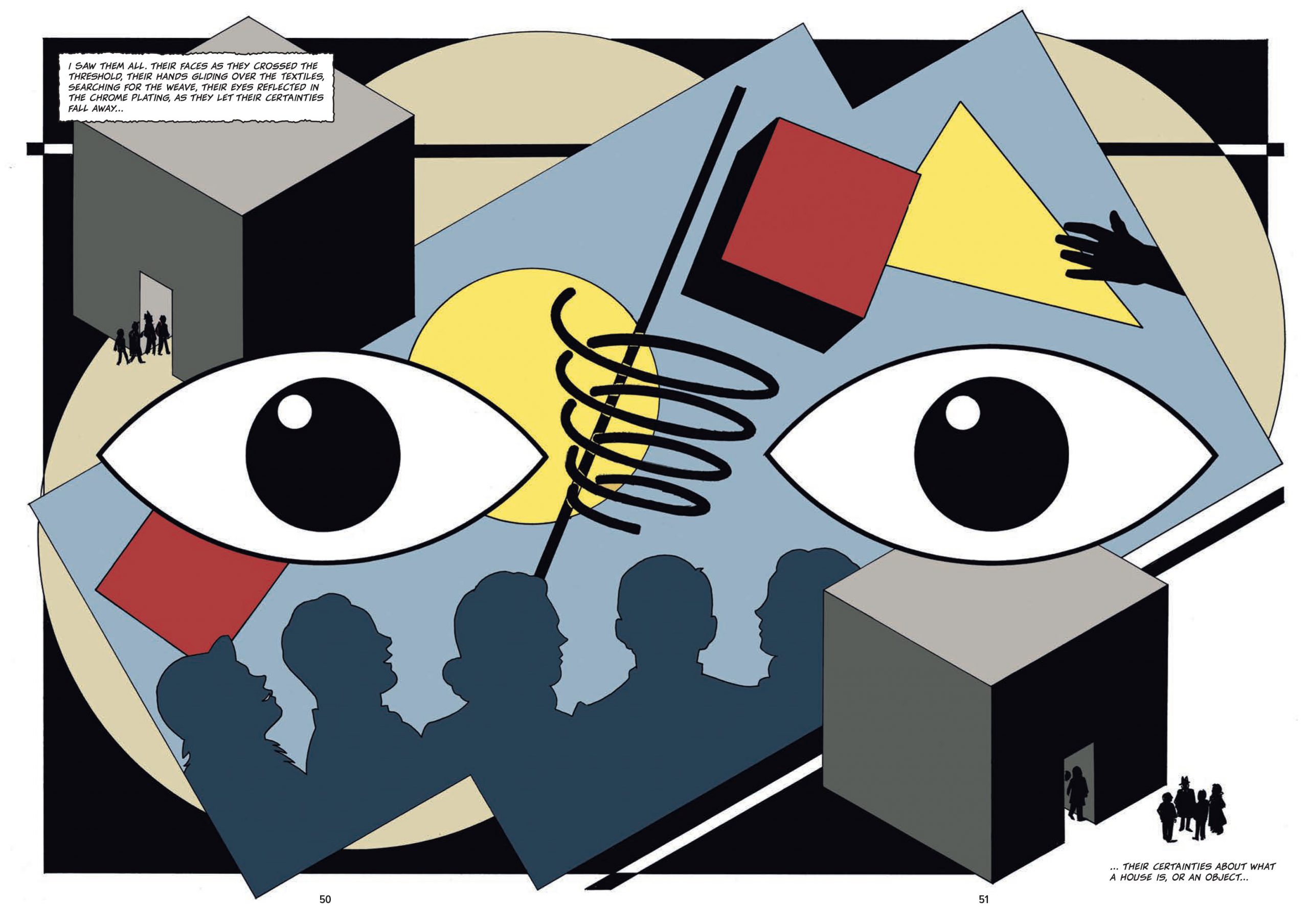

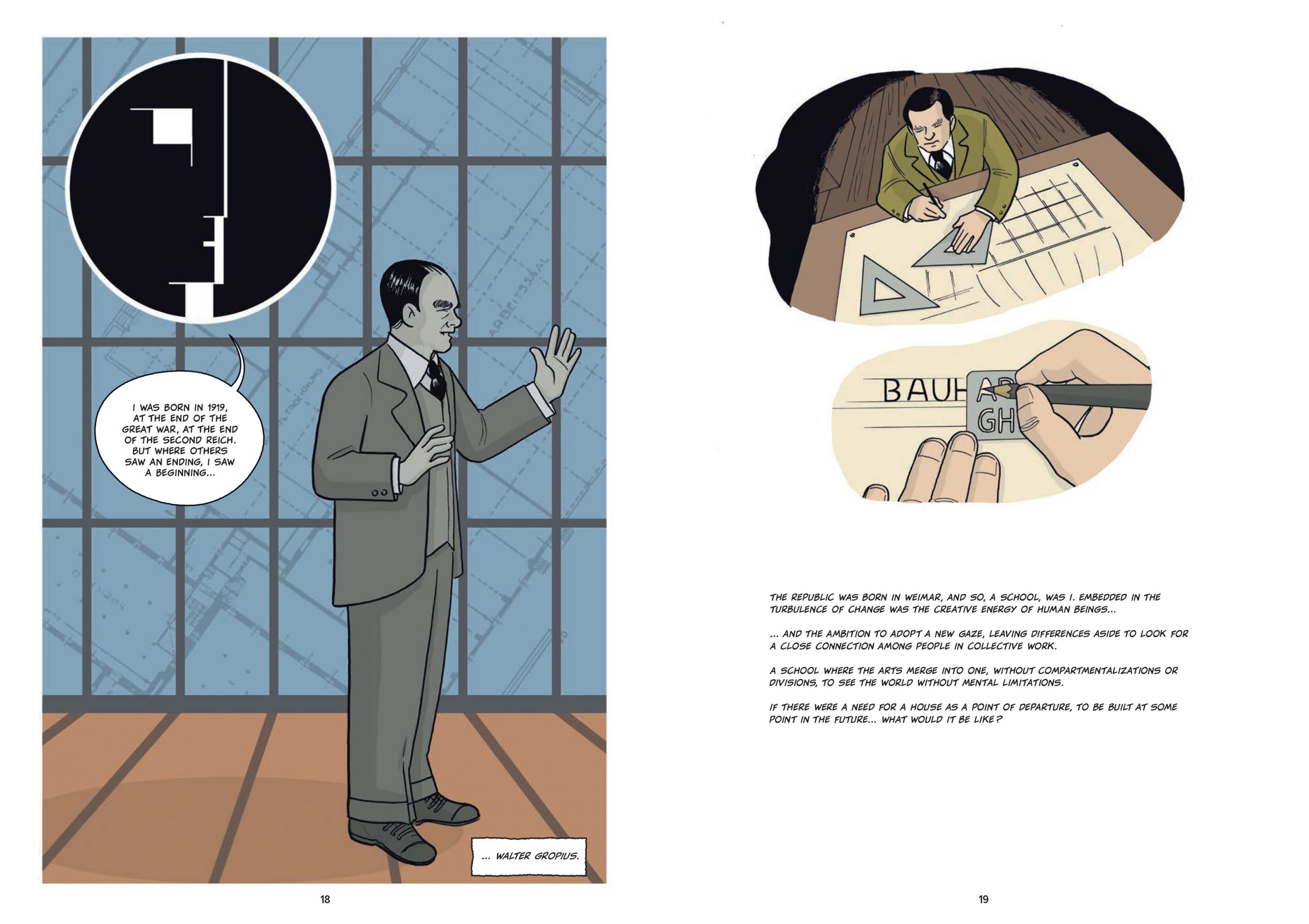

Written by Valentina Grande and illustrated by Sergio Varbella, Bauhaus – A Graphic Novel has a neat approach, letting the concept of the Bauhaus itself narrate its story. As an introduction to the topic, it’s excellent. The ligne claire

(‘clear line’) style of drawing (a la Tintin) chimes with the architectural style of the Bauhaus, placing the reader immediately within that world.

You can almost hear the silence in the opening frames, which depict the largely empty corridors and stairwells of the Dessau and Weimar campuses. There is a clarity to the art style and the narration that is welcome throughout, streamlining what can be a daunting tangled history with a sprawling cast of characters. At its best, there’s a lively inventiveness that feels true to the subject matter, moments when ideas seem to escape from boxes.

“You can almost hear the silence in the opening frames, which depict the largely empty corridors and stairwells of the campuses”

The problem arises with the ‘novel’ part of ‘graphic novel’. While the central conceit is imaginative and full of potential, suspension of disbelief never really happens. This is partly a matter of tone. There’s a childlike quality to the narration, with the Bauhaus listening in on its inhabitants, wanting to join in the fun, but it’s written the way adults think children speak rather than the surprising anarchic ways that they do.

This extends into the characters themselves. We see little of Walter Gropius’ quiet charisma or Paul Klee’s poetic mysticism for example. Instead, they are featured together almost like marionettes, speaking in exposition dumps, with the drawings as stiff as the dialogue. It’s a shame as all the components are there for success but it feels, presented with such a vast multi-layered and peopled topic, as if the creators have opted for an ill-advised ‘tell, don’t show’ approach.

“The desire to be definitive and to summarise robs the book of dynamism and life. It’s the Bauhaus but as a kind of puppet theatre”

This is understandable, to an extent (how would one begin to encapsulate Kandinsky, for example?) but it is also a waste of priceless material. Instead of brief textbook summaries of each artist, it would have been much more effective to have glimpses or vignettes into their lives. The desire to be definitive and to summarise robs the book of dynamism and life. It’s the Bauhaus but as a kind of puppet theatre.

Such criticisms may seem harsh, but they are born from frustration at how close the graphic novel gets to greatness. Making a book about the Bauhaus in the style of the Bauhaus is an idea with promise. Despite its flaws, the book is a worthwhile addition to the library on the topic and easily one of the most accessible ways in. It is informative, focused, occasionally poignant.

“The closer you try to get to defining what the Bauhaus was, the more elusive it seems to become”

It shares however a common problem with many Bauhaus biographies: it’s not quite weird or dark enough. The appeal of the Bauhaus was not just its marriage of beauty and utility, its erasing of the boundaries between disciplines, its focus on relationships and mutualism in the creative process. It was also that it was a brief but spectacular burst of light and colour between two periods of immense darkness.

There is hope and tragedy, and it must be said romance, that is missed here. There is very little shown of Gropius’ harrowing war experiences, which may have lain behind his desire to renew the world. There is little shown of the fate of the Bauhaus and its people after its fall. The life and death of Otti Berger, for instance, would have been an immensely powerful example of what was lost.

Without darkness to contrast with, the light in this book doesn’t inspire as it should, and for all its creativity and interest, the book feels orthodox. It loses that mysterious spirit of the Bauhaus. Efforts are made, counter-productively, to justify our interest in the art school by connecting it to our contemporary concerns, when all along all that was needed was to simply allow the Bauhaus to tell its own story.

Darran Anderson is an author and journalist. His latest book, Inventory, has been shortlisted for the PEN Ackerley Prize

Valentine Grande and Sergio Varbella, Bauhaus: A Graphic Novel is published by Prestel (out 5 April)