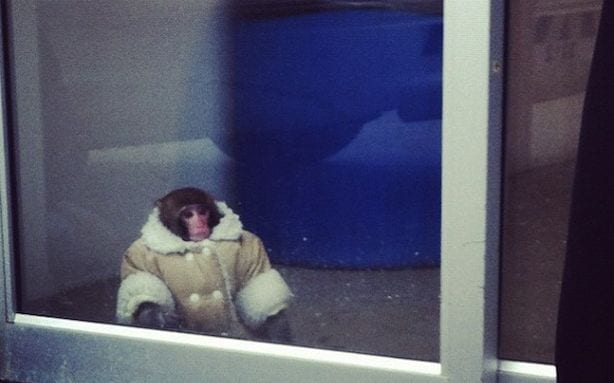

A monkey, particularly one that is fashionably dressed in a sheepskin jacket, is difficult to forget. Put it down to the staggering ninety-six per cent match between the genome of the great ape species and that of humans, or to the uncanny exuberance of an animal wearing any clothes at all, but a monkey in garb has the power to capture our imagination like no other. It is perhaps unsurprising, then, that the sight of the swaddled monkey in question is seared into my brain forever. Spotted on 9 December 2012 at a branch of Ikea in Ontario, Canada, it wasn’t long before the image became an internet sensation.

Snapped by local punter Bronwyn Page and swiftly uploaded to Twitter, it was the image that launched a thousand articles, followed by an incessant swarm of memes. “Shearling Coat-Wearing Monkey Found Wandering Around Canadian Ikea”, Gawker reported at the time. “The unnamed monkey is seven months old, and no one was really sure how it got there. Or why it was wearing such a great coat,” Buzzfeed blared. A parody Twitter account, supposedly belonging to the monkey itself, was set up, with their first tweet poking fun at the furore: “What’s all the fuss about? #ikea”

“It took just one image to ensure that the entire internet was watching”

The following day, the answers began to trickle in. The monkey was—rather aptly—named Darwin (after Charles), and had been left in his owner’s car while they did a spot of shopping. What the owner hadn’t banked on was the monkey’s deft ability to unlock the vehicle and hop out into the carpark, where he began to attract attention from the public. Only a handful of people were there to witness Darwin’s curious get-up firsthand, but that didn’t matter. It took just one image to ensure that the entire internet was watching.

It is a curious moment to look back on now, at a time when “going viral” has become part of our everyday lexicon. In 2012, Twitter boasted 185 million users; presently, 1.3 billion accounts have been created. Viral posts will receive thousands of retweets and shares, as a wider collective consciousness asserts itself through the affirmation of the group. These points of connection are inevitably simplistic but undeniably grabby. And what could be more universally appealing than a monkey in a sheepskin jacket?

Reminiscent of the classic toy depicting a monkey with a miniature cymbal, popular from the mid-1950s onwards, the story evoked a childlike glee at the sight of a primate dressed as a human. There is an undeniable synergy between the blandly ubiquitous familiarity of Ikea, remarkably consistent across its 267 stores in twenty-five countries, and the seemingly universal popularity of Darwin the monkey. He is not just the monkey in the jacket, but the monkey spotted at Ikea; the internationalism of the Swedish retailer cannot be overlooked in his rise to fame.

“The story signalled a shift in our contemporary visual culture, at a time when the news and social media were rapidly colliding”

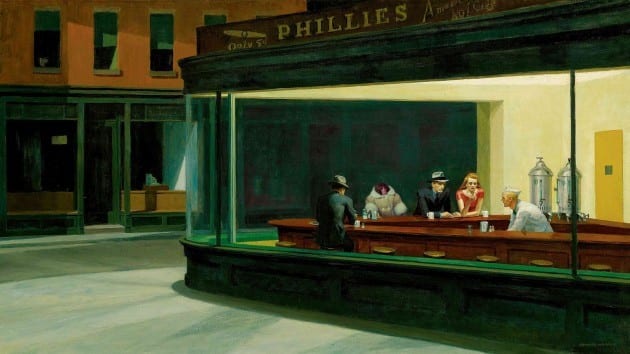

Cue countless cut-out Darwins pasted into digital scenes from the Ikea catalogue. His easily recognisable profile has also found its way into famous works of art, from Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks to Damien Hirst’s shark in formaldehyde. Even before he had been rehoused in a local primate sanctuary (where he remains to this day), this monkey had become much more than an animal in need of rescue. Like all good memes, he was adaptable to any number of scenarios, and just absurdist enough to offer some relatable light relief.

Darwin, the monkey in the shearling coat at Ikea, has entered into the internet’s collective memory. The story signalled a shift in our contemporary visual culture, at a time when the news and social media were rapidly colliding to create a new form of digital consumption. The power structures of reporting have continued to dissolve, and the immediacy of an image can be all that counts in the age of algorithms and ruthless popular opinion. Memes might seem meaningless but they hint at a desire for wordless unanimity, when political division pushes us to find even the most fleeting of connections.