Art has long been a site to articulate internal crises and emotional turbulence. Outside of the fine art world, a growing number of illustrators are turning to pen and paper to depict their mental state, using image-making to deal with fear, looming psychosis or anxiety.

While it might sound paradoxical, individual visual expression is now officially recognised as a way of helping people connect with others, and is being encouraged by medical practitioners for the first time. In the UK, art practice is entering the doctor’s surgery: in 2018 a new £4.5m fund was rolled out to twenty-three areas in England to support GPs in prescribing creative activities instead of anti-depressants.

The scheme aims to identify and link people who are lonely or isolated and need support with their mental health within funded, safe environments in which they are encouraged to create. It’s part of the government initiative described in policy documents as “universal personalised care”. Many people who are naturally inclined towards drawing and mark-making have found themselves teaching sessions as part of the scheme, but there have long been other examples of people outside of “official” NHS schemes nurturing similar ideas.

“Art not only helps with our mental health but also can provide us with a profound sense of wellbeing, psychosomatically and holistically”

Art therapist Alex Monk says that “art not only helps with our mental health but also can provide us with a profound sense of wellbeing, psychosomatically and holistically. The sense of wellbeing that is borne out of making art is, importantly, what we feel in every part of our bodies—not only cognitively. To just know something is not, after all, what makes us feel better. It is the connection that we have with the process of creating, either in commune with our creation or through connection with others who share our process.”

This is something I can relate to on a personal level: a couple of years ago I was invited to show my art in an exhibition about depression, and decided to look at a major personal crisis to create my work (which has since become an extended visual essay, Love on the Isle of Dogs). In the early 1990s I was married to a man who was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia—a period I had tended to compartmentalise. But as I started to sketch out what I remembered of my internal difficulties, and draw my former husband, it made me think about how I hadn’t, and couldn’t, understand what was happening inside his mind. It’s incredibly challenging to try and draw someone else’s paranoia with true empathy.

- Love On The Isle Of Dogs, Jude Cowan Montague

Aside from the difficulty in articulating others’ issues from your own external viewpoint, what became clear from the project was the many difficulties we (and I’m sure so many others) encounter when dealing with mental health professionals. As such, it’s little surprise so many creatives take things into their own hands.

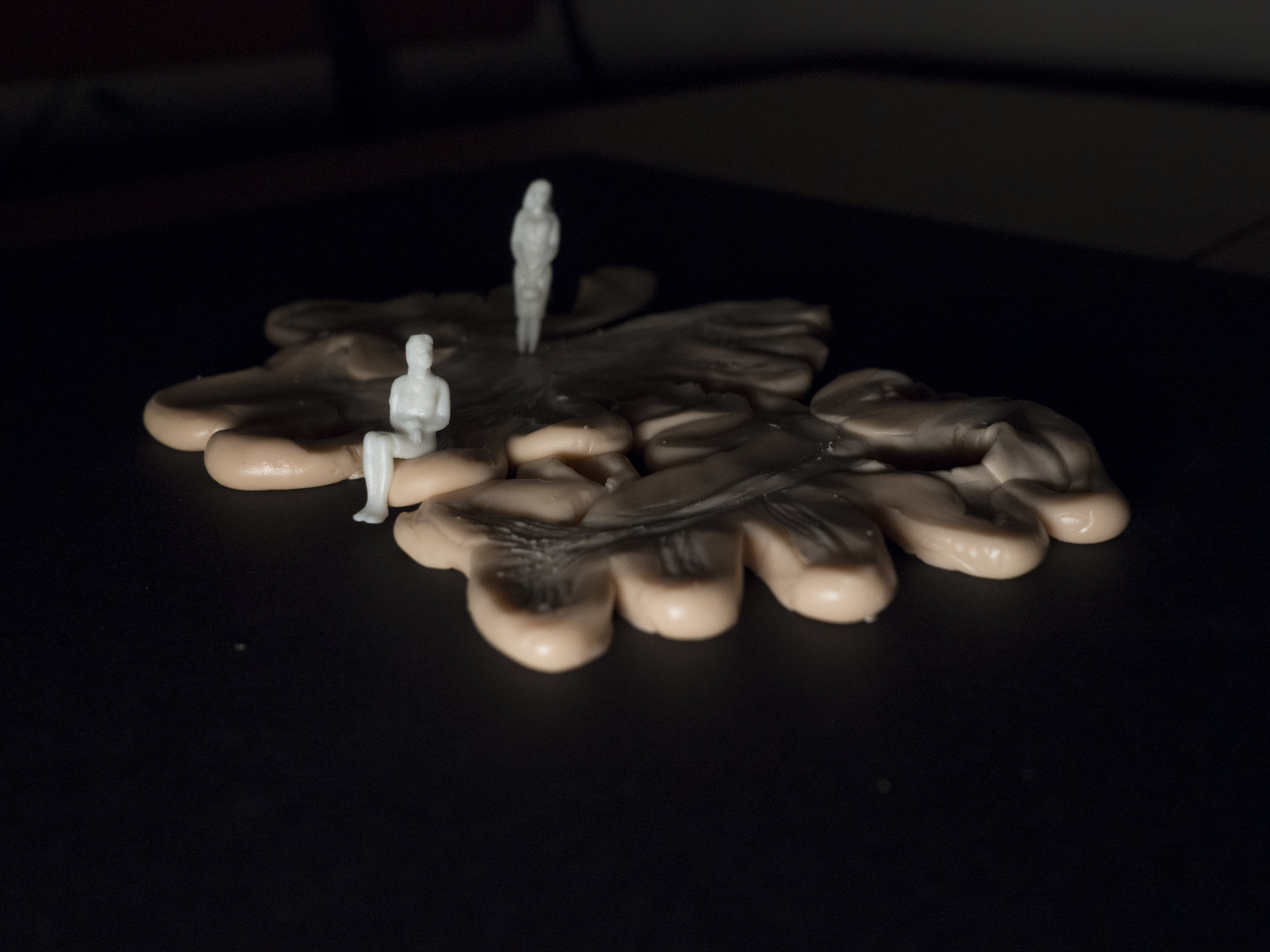

Merlin Strangeway, who recently spoke at the Illustrating Mental Health Symposium at the University of Worcester, is a skilled medical artist who has been running group projects to share her knowledge and work with others. The aim is to help them navigate their own minds, using techniques like modelling, storyboard and sketching. In The Folds of Consciousness, a series co-designed with patients, she took traditional anatomical wax and architectural figurines as a material basis for shooting story-based sequences on the concept of loss, memory, safety and uncertainty.

These models look to help answer the often-problematic and sprawling question, “What does it feel like to have dementia?” Strangeway says that some pieces “explore the isolating, disjointed nature of losing one’s memory,” while others “explore a sense of loss as a weighted blanket, trapping but familiar.”

“Outsider art has given people a means of exhibiting and talking about their work”

Through other sides of her personal work Strangeway breaks down the division between artist and patient by focusing on her experience of chronic insomnia and its side effects of fatigue and disorientation. “I don’t find it particularly distressing (most of the time) but I do find it quite an interesting state to sit in and make work in,” she says.

Much of the illustration that aims to express dark feelings is influenced by romantic ideas of “Sturm und Drang” (literally translated as “storm and drive”, a literary and artistic movement born in late eighteenth century Germany, characterized by the expression of emotional unrest and a rejection of neoclassical literary norms) and early theatrical forms of horror.

This is the case with Swedish creative Emmy Wahlbäck, who specialises in work that often probes frightening, out-of-control emotions by anthropomorphising them as video-game characters. In her series Far from Euthymia she turned to her own diagnosis with bipolar disorder for inspiration (“Euthymia” is the word used to describe a normal, tranquil mental state in those affected with the condition).

- Emmy Wahlbäck, Excitations, from the Far from Euthymia series

Wahlbäck’s work uses Greek mythology as a resource to name goddesses of depression and mania. These dangerous figures are joined by healing figures, such as the Neurotransmitter Nymphs, that work to keep balance in the forest of synapses. Medication figures as an important part of her story. For one sequence Wahlbäck rendered hospital bed sheets as a collage of the information pamphlets from her boxes of lithium. She drew Achlys, who brings eternal night and the mist of death, with ink manipulated by the edges of pill packets. At the end of her tale, she says, there is still hope—but nothing is entirely certain.

“When I do manage to sit down to draw it usually makes me feel better”

Whether it demystifies or improves our sense of agency over medical conditions, helps us combat isolation or simply makes us feel good, it’s clear that illustration can be a powerful tool in aiding those with mental health conditions. Although art therapy is a relatively young invention, and something only recently formally validated by the medical profession, Monk asks us not to forget the outsider art movement that’s been around for as long as art itself. “This has given people a means of exhibiting and talking about their work where they may otherwise never have been provided with a platform,” he says. Wahlbäck, currently weathering the gloom of Sweden’s short, bleak days says that the seasonal lack of energy generally takes its toll. “But when I do manage to sit down to draw it usually makes me feel better.”