Liv Fontaine stated two years ago in an interview with Elephant that she was looking to settle down in the countryside and “become impregnated by a man of maybe 6ft 2, medium build, with a job”. She also hoped to buy a Citroen Picasso. An artist known for her powerful, frequently hilarious performance pieces and drawings infused with a DIY spirit—with her tongue often firmly in cheek—Fontaine is still waiting to realise that dream.

Although she is still without a driving licence, her art practice is decidedly on the ascendent. Fontaine has documented her own chronic illness over the years, making this deeply personal struggle as much a part of her work as the more politically charged moments. These dual aspects, usually glued together with a smidgen of smut, converge in her unflinching portrayals of the female body and her confrontationally playful modes of address.

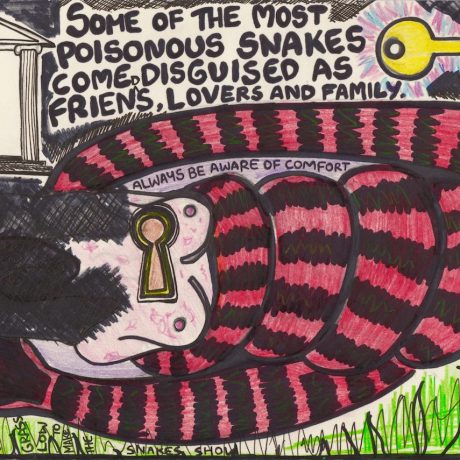

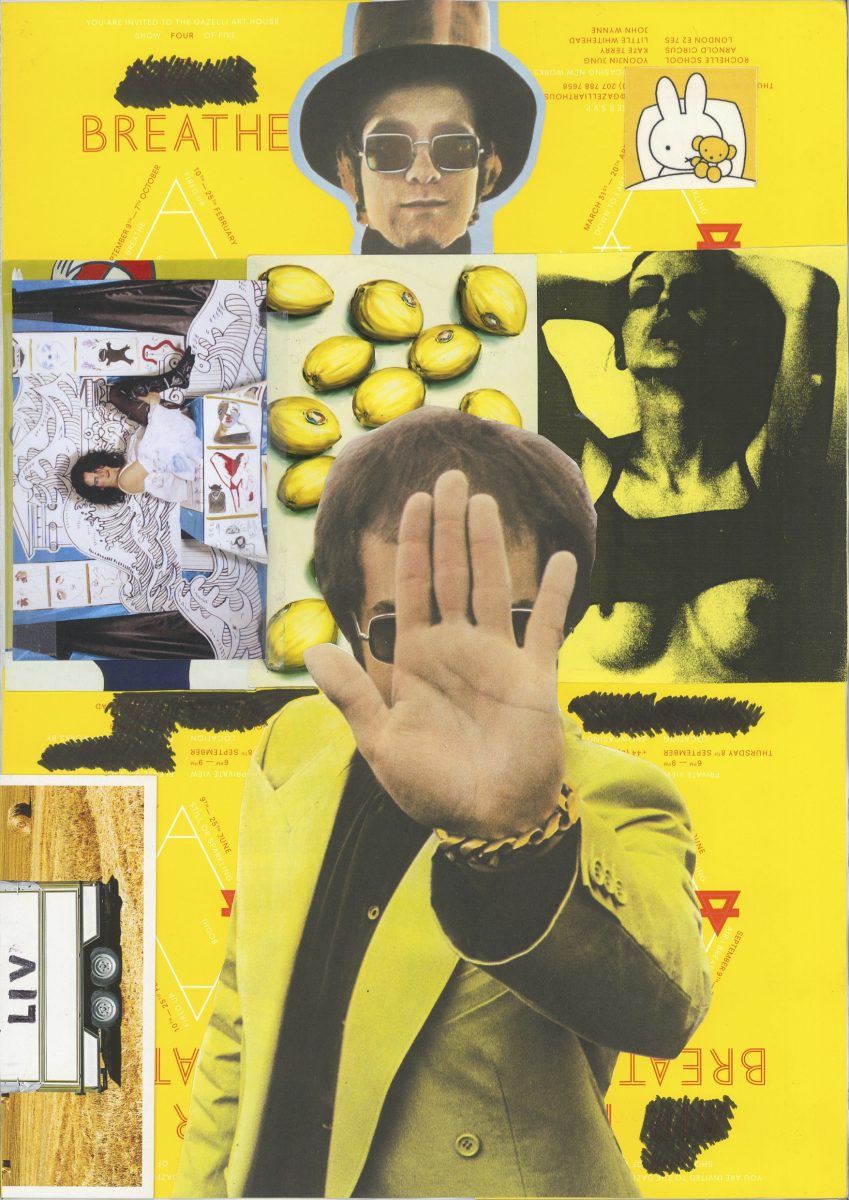

- Liv Fontaine, sketchbook page, 2012

Her latest solo show at Richard Saltoun gallery titled HURT AGONY PAIN LOVE IT, curated by Róisín McQueirns, presents drawings that hint at “the fine line between pleasure and pain,” as Fontaine puts it. “The drawings focus on my own extreme emotions and are often responding to some heartache or illness, as well as feelings of rejection, confusion and destruction,” says Fontaine. “The drawings are gloomy in that sense but my exploration of this gloom feels more masturbatory, celebratory and pleasurable… Misery makes content and I’m at my most productive when I’m most miserable.”

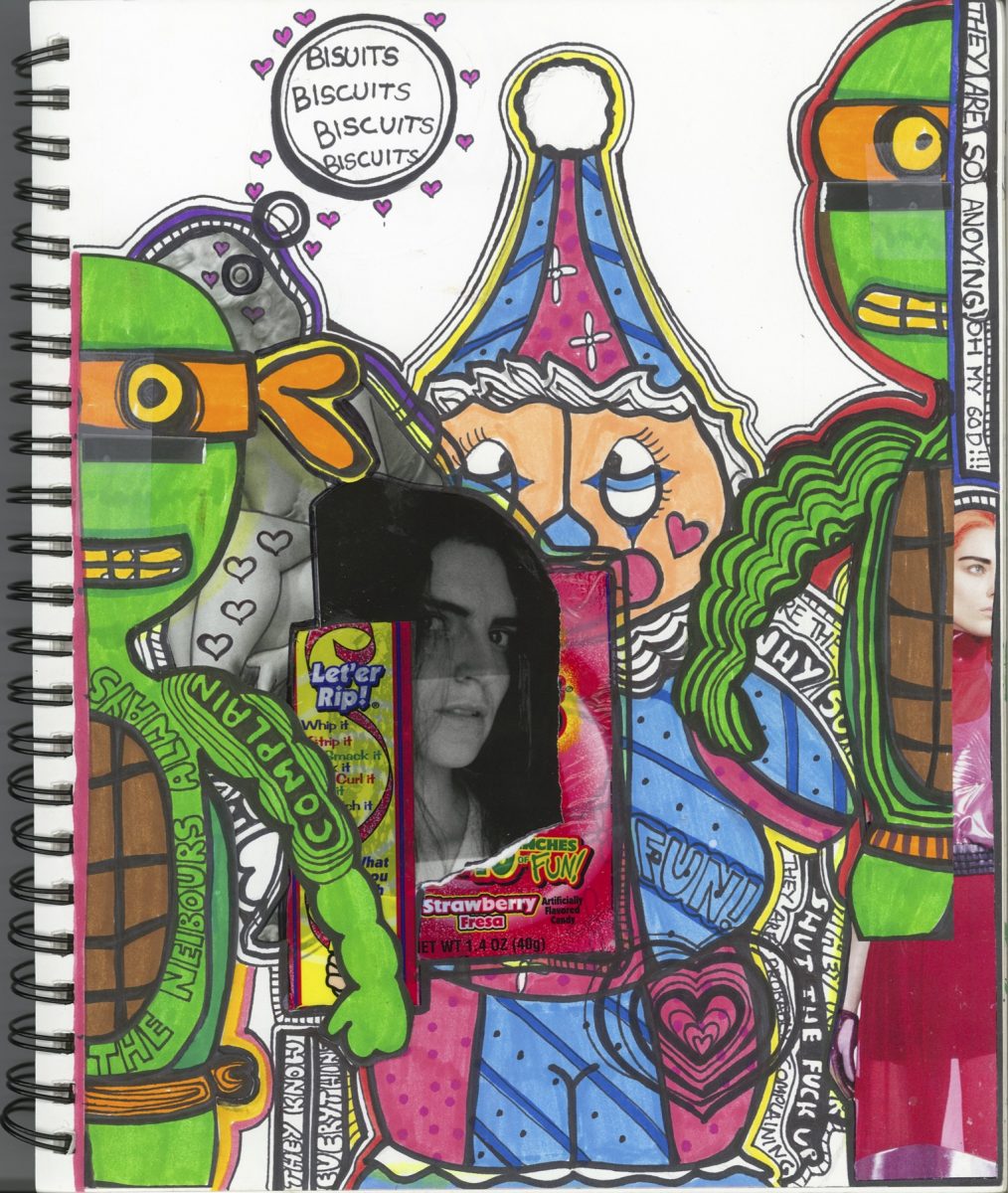

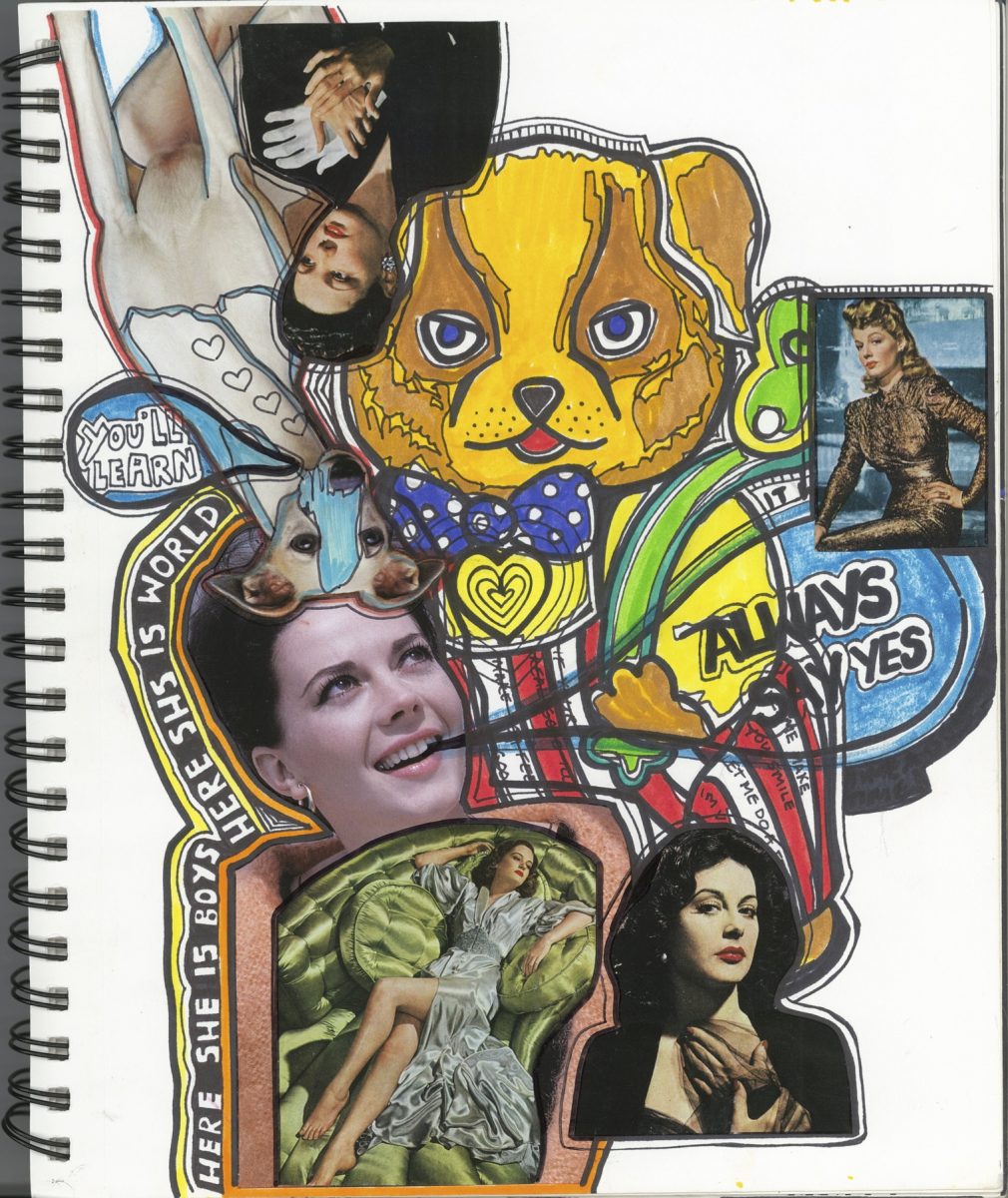

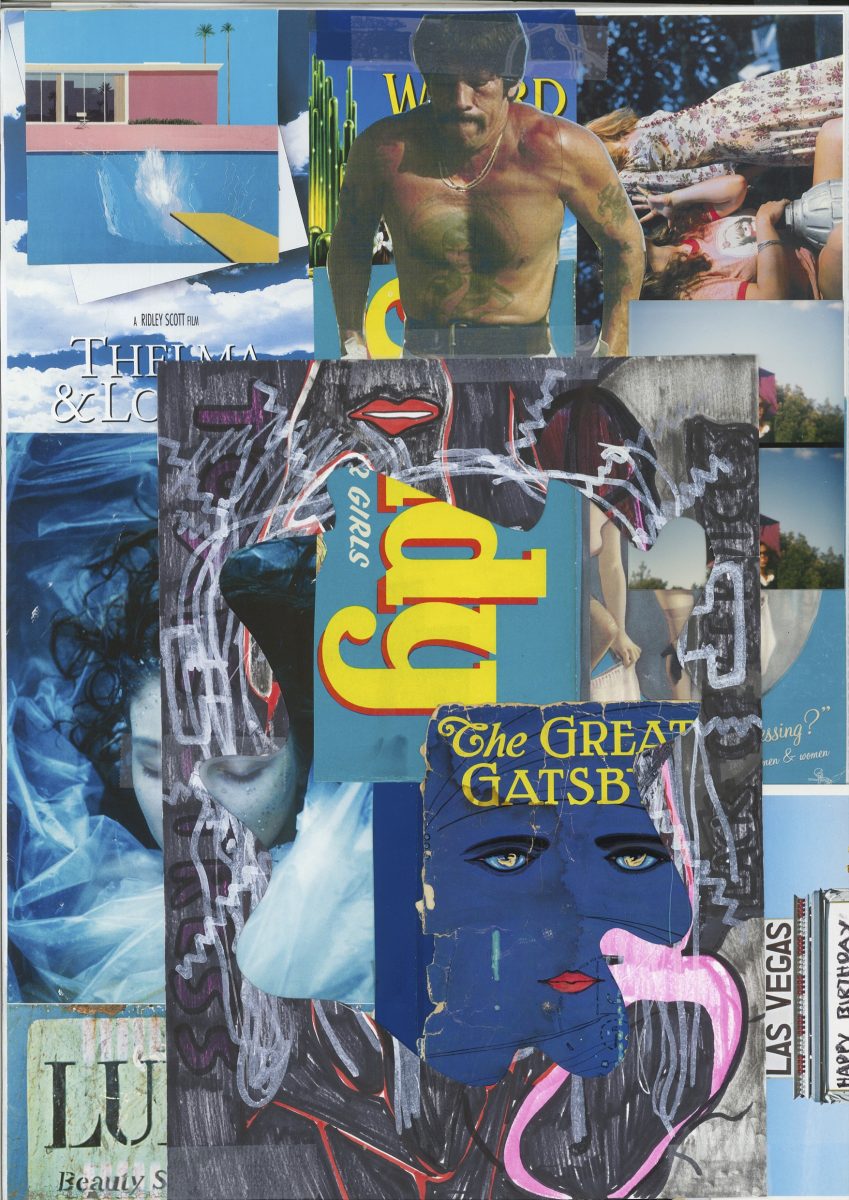

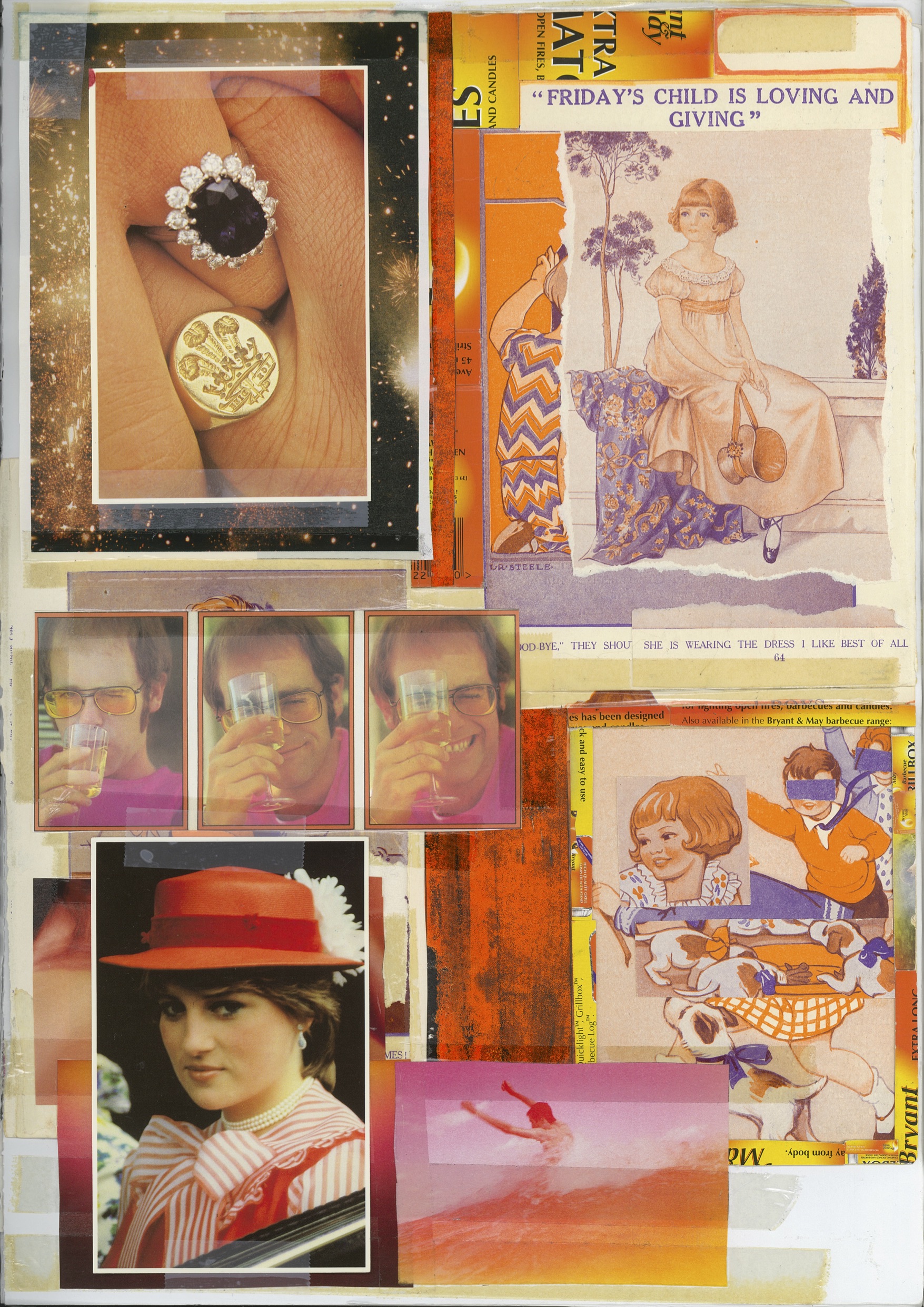

The exhibition also features an image scanned directly from one of the artist’s sketchbooks. These sort of doodles, drafts and documentation offer insight into an artist and their work that audiences are rarely privy to. In the first of a new series of pieces delving deeper into artist’s sketchbooks, Fontaine discusses how she uses them, and the potential of the sketchbook for offering us a “journey into the mind.”

What might your sketchbooks tell us that we wouldn’t otherwise know about you and your work?

The visual sketchbooks aren’t really preparatory in terms of future ideas and work—they are archival. Many of them feature images that I tore out of magazines in the early noughties and then carried around with me for the last 20 years between about 20 different homes. I started the collage books when I was a teenager doing my Art GCSE. Back then I only listened to angsty female singers, and the collages felt very fitting. What the sketchbooks tell you is that I am a nostalgic hoarder who can’t let go of the past.

“My sketchbooks tell you that I am a nostalgic hoarder who can’t let go of the past”

How important are notebooks and sketchbooks to your practice?

I keep notebooks but these are for performance writing, or for quotes that people have said, things that I hear on the TV or that I read and think are interesting or strange. One page will say “Small problems have massive faces”, which my friend Rosa said to me. The next will say “Hysterical women betray themselves with erotic smiles”, which I read in a book about Ruth Ellis, the last woman to be killed by capital punishment in the UK for shooting her lover dead.

I plan performances by writing in notebooks and Google Docs, and then recording rehearsals so I know what to work on. This was a practice I introduced about three years ago when I started to take the idea of entertainment more seriously. I wanted to better understand the power dynamics between audience and performer—the manipulation and the vulnerability… I wanted to give people a good show: make them laugh, or maybe cry. To do this I needed to be better prepared and more focused. Before my planning was minimal and normally involved drinking a bottle of white wine before the performance and a bottle of white wine afterwards.

When you spoke to us in 2019 you said, “With the drawings I felt freedom in all my fuck-ups”. Often, sketchbooks show us things that artists don’t necessarily want us to see. How comfortable are you with those sorts of revelations?

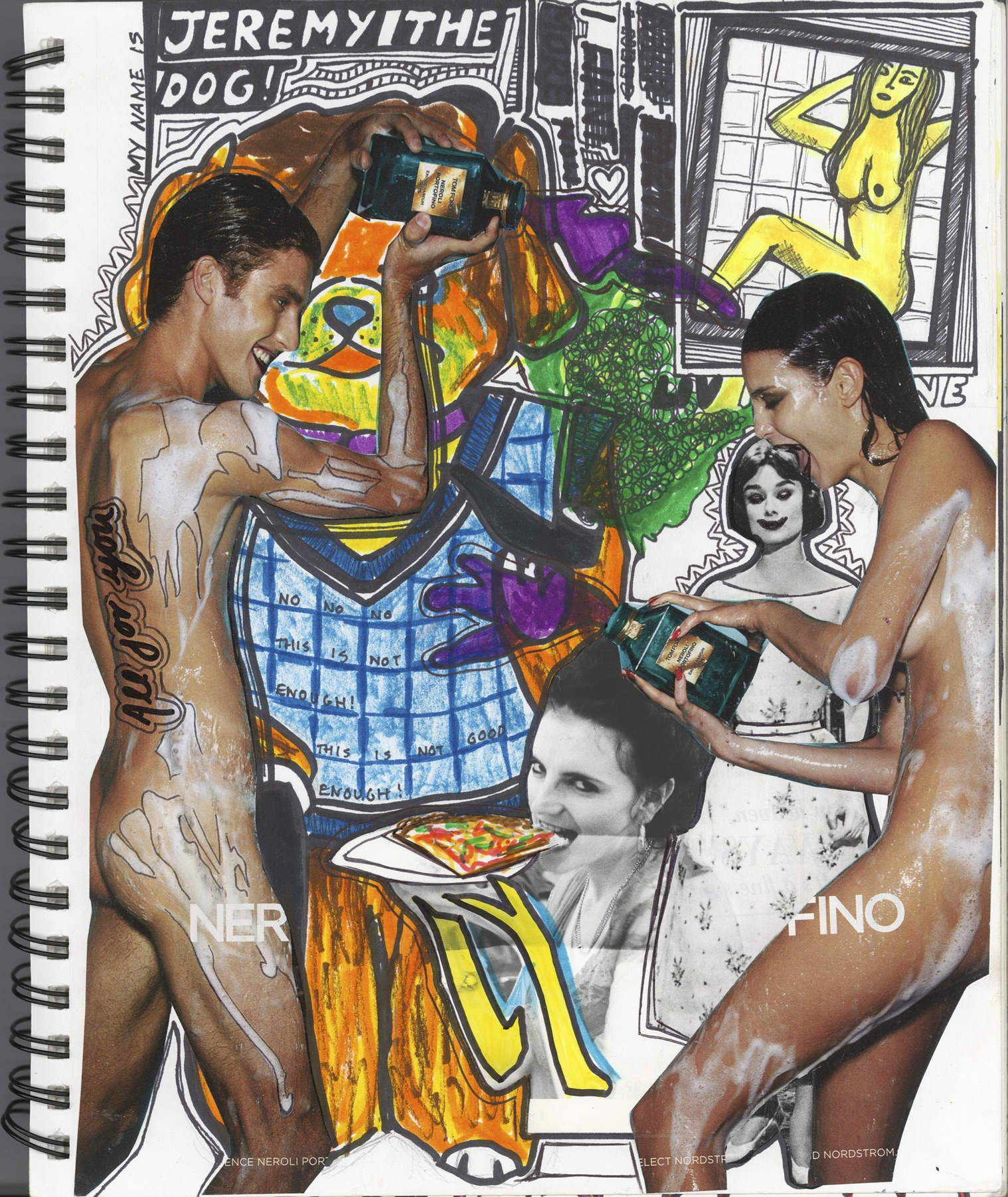

There isn’t a plan for the drawings. They start as still-lifes, taking inspiration from my own collection of ornaments and objects; then I expand on them with a narrative or a feeling. If they don’t look right I just carry on drawing until they do… I don’t give up on them. It’s a live editing process where you can see all of my mistakes. The mistakes are bad spelling, bad politics, bad health and bad men. It’s not like I don’t have any modesty but it’s good to talk. Honesty is radical because we are constantly being lied to by authority, and authenticity is necessary for an emotional response—whatever that may be…

- Liv Fontaine, sketchbook page

What for you is the relationship between sketching, or drawing, and performance?

I find performing cathartic but not therapeutic; not healing but exhilarating and gaping. The drawings, however, are more therapeutic, although I don’t like that word—perhaps self-reflective is a better way of describing them. They are current, made in real-time in the situation that they describe (a romantic relationship, precarious politics or impending doom). The process is not material-based but centres around the processing of my own thoughts about the situation or scenario of which I’m making work. It has helped me process my own illness by giving me an opportunity to communicate it, isolate it and see it in a different light which is beyond physical.

Drawing feels like an obsessive and compulsive desire to make completed work, since nothing I do ever seems to end (indecisiveness has been a main theme throughout my life). The drawings have their own life independent of me; which is freeing in a way that contrasts performance, as the performance lives inside the performer.

“Honesty is radical because we are constantly being lied to by authority, and authenticity is necessary for an emotional response”

What are your go-to sketching materials?

I use whatever is in front of me and I buy all my art materials in WH Smith. It’s best when the marker pens start running dry and the marks become desperate. I like cheap pencils and draw with Tipp-Ex and biros. I try my best to avoid the plague of tweeness which can be easy to fall victim to when drawing. I am an active opponent of this in life and art.

Liv Fontaine (selected drawings), Don’t Let The Bastards Grind You Down, 2021

Liv Fontaine (performance), Hubris Programme, Glasgow International 2021

A book of Liv Fontaine’s drawings will be published by cpress books in summer 2021

VISIT WEBSITE