It’s 1974. A graduate student at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) is drifting around the city, a young photographer in his twenties with no studio and no place to go. Land is cheap in the sprawling suburbs, and large houses line the wide, empty streets. Everybody drives in LA. John Divola walks and, as he goes, spots boarded-up windows, front porches in states of disrepair and collapsed roofs—the derelict details easily missed when cocooned in a fast-moving car. He finds abandoned houses all over once he begins to look, their owners evicted or gone in search of a better life. One day, he kicks a door down—it’s not difficult—and he’s in amongst the cracked walls and forgotten debris.

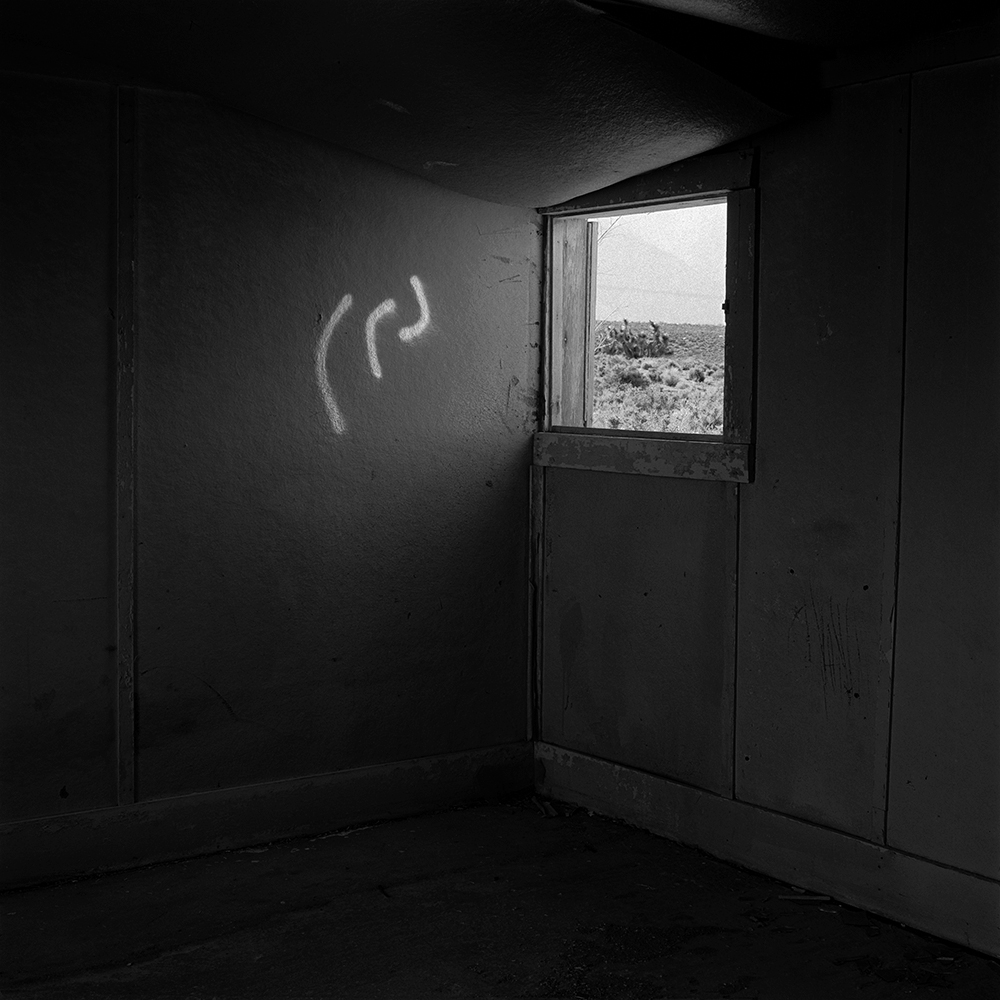

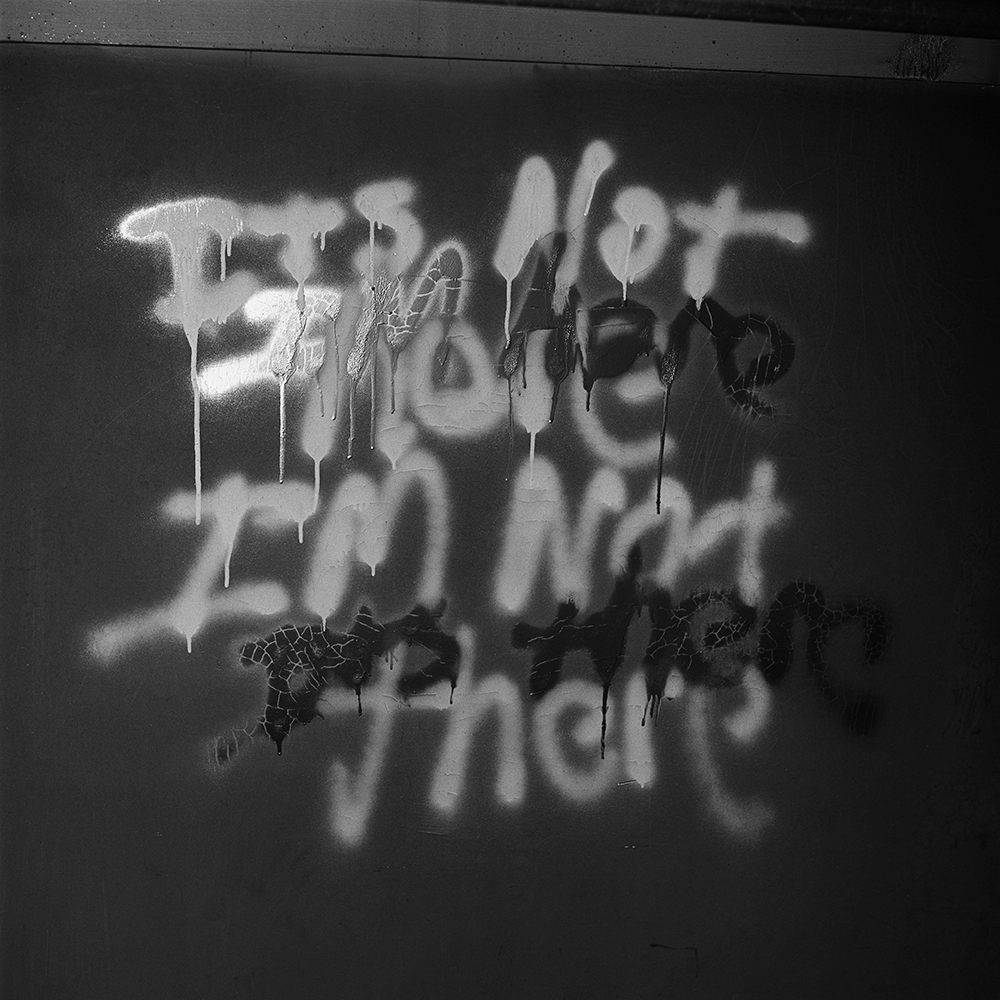

Vandalism, Divola’s first photography series, started here. These dilapidated properties became his short-term studios, and he made himself at home in them. Using spray paint, string and cardboard, he vandalized their worn interiors with abstract, graphic graffiti, before photographing them in stark black and white. Swirls and constellations of dots in black and silver paint mark the walls, suggestive of an unknown ritual carried out on these grounds. Past lives, real and imagined, are conjured in the resulting images, as Divola deliberately merged documentary photography with staged interventions. As he explained in one of his earliest interviews in 1978, “I’m just changing things to see what happens. I’m no more interested in my own marks than I am in debris on the floor or the way a curtain flies up because the wind’s blowing in.”

“Past lives, real and imagined, are conjured as Divola deliberately merged documentary photography with staged interventions”

I first came across the Vandalism series last year at the Whitechapel Gallery in London, where it was included in the expansive and yet wonderfully intimate exhibition A Handful of Dust, curated by David Campany. An entire wall was lined with more than thirty of the 14 x 11-inch prints, hung closely together as if to create an immersive experience of almost entering into the vacant houses as Divola once did. The effect of seeing them together also made clear their strength as a series—something that is carried forward in a new book published by Mack this March.

For the first time, Vandalism will be available as a monograph, beautifully reproduced with a full page given to each photograph. Text is kept to a bare minimum, in keeping with the immediacy of the images, which still feel transgressive to look at today. With their conceptual directness and visceral engagement with landscape, they set in motion a career that has seen Divola explore everything from bombed-out beach shacks in Malibu to dogs chasing his car in the desert. Straight from those empty LA streets, it is a vivid insight into where it all started.

All images courtesy Mack books and John Divola