Writer Phin Jennings explores the ideological and political frameworks behind artist, filmmaker and composer Imran Peretta’s upcoming exhibition at Somerset House Studios and speaks to the artist about the project’s history.

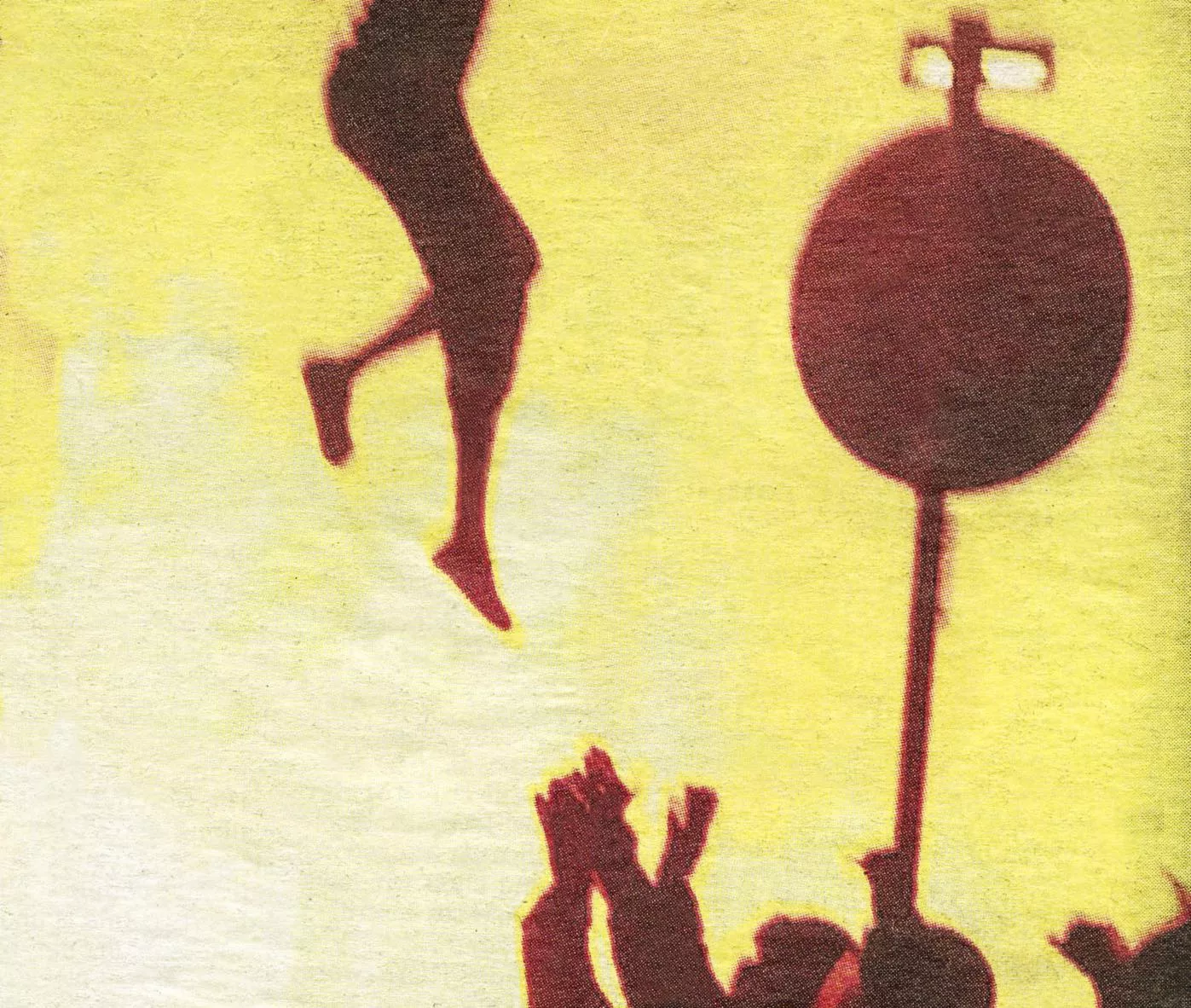

Reeves Corner is a small plot of scrubland in Croydon. The building that once stood there, a furniture shop, was burned down on the 8th of August 2011 during the riots that spread across the UK following Mark Duggan’s murder. What remains, thirteen years later, is the subject of A Riot in Three Acts, Imran Perretta’s upcoming exhibition at Somerset House Studios. The exhibition doesn’t focus on the fire itself or the events leading up to it, but on what has happened since — on Reeves Corner and in Britain at large: very little. “Stasis,” as Perretta puts it, “gradual decay.”

He describes the exhibition as an exploded film, three components — a set, a soundtrack and a prop — not synthesised into one work but blown apart and presented separately. It will comprise a recreation of Reeves Corner as it is today — a fenced, flat, fallow expanse — alongside a score written by Perretta and performed by the Manchester Camerata and the artist’s old BlackBerry mobile phone playing footage of the fire.

Why choose such a small site as the subject of the show? “What you hope for in any work that you make is that, by being ultra specific, you unlock something universal,” he explains. The story of the London Riots touches on tens, hundreds, of years of British history, but it is important to him that his exhibition has a specific locus within the world today.

He is at pains to demonstrate that political realities are concrete ones — not abstract ideological weather fronts that hover above us, but textural, material facts that touch our lives. In bringing Reeves Corner into Somerset House’s Lancaster Rooms, he reflects the riots and their legacy, not as a set of ideas or a thought experiment, but as something tangible. “These things are intimate and material,” he reminds me.

What was that reality to Perretta? “The riots were a really early flashpoint where people said we’ve had enough,” he tells me. They came the year after the austerity-addicted Conservative-led coalition government came into power and as a direct reaction to Mark Duggan’s murder. “Violence is structural; denying someone access to public services is an act of violence,” he says, “it’s that form of violence that most affects people in their day-to-day lives.” The mainstream media characterised the riots as mindless destruction, but that point of view ignores the litany of surreptitious acts of state violence that precipitated them, and that they sought to call an end to. Put simply, in the artist’s words, “you have to look beyond the person who lit the match.” After our conversation, on his recommendation, I watch a BBC interview from 2011 with the late broadcaster and writer Darcus Howe, who echoes this idea. “I don’t call it rioting,” he says, “I call it an insurrection.”

At the same time, then mayor of London, Boris Johnson was spinning the opposite story: “it’s time we stop hearing all this nonsense about how there are deep sociological justifications for wonton criminality and destruction of people’s property,” he told reporters. It was this story that the press and the government impressed on public memory. The rioters’ voices of righteous anger at structural violence were retroactively transformed into calls for destruction for destruction’s sake.

This is the world where Perretta stages A Riot in Three Acts, one where Reeves Corner stands as a monument marking the death of a dream for change. “However unspectacular and neglected it is, it holds all that energy,” he says. It’s the same world that we find ourselves in today — still in the wake of that dead dream; our country has experienced thirteen years of state violence since, all presided over by this desolate patch of land in Croydon.

It’s only right, then, that the exhibition’s soundtrack is a requiem — a traditional type of composition written to soundtrack a funeral. “There’s Requiem for A Dream,” Perretta quips, “I would have called it that, but the name was already taken.” A Requiem for the Dispossessed is a long, mournful piece of music in nine parts. Its overlapping violins lament the bastion against state violence that Reeves Corner could have represented, and the changeless reality that it instead symbolises.

It is here, with this requiem, that he touches on something universal. Reverberating around the distinctly unspectacular space that is Reeves Corner, it becomes a memorial march not just for the steamrollered dream that the 2011 riots could have changed things in the UK but for every other hampered attempt to stand up against structural injustice, before and since. “Reeves corner is like an unmarked grave,” he says, “what we’re trying to do is turn it into a place where one can memorialise.”

Is there something inherently cynical or pessimistic about making this barren landscape a monument for such meaningful causes? Not to Perretta: “I’m no nihilist; I always want to leave with a sense of hope — because what’s the point otherwise?” The requiem ends, faithfully to the form, with a short movement called In Paradisum. During this section, the gates of heaven open and the dead are invited into the next life.

In A Riot in Three Acts, that next life involves reflection, learning and exchange. Perretta has invited academics, writers, artists, activists and Croydon locals to activate his set with a series of discussions and workshops. “This is about trying to repopulate that space, trying to give it some soul,” he says, “if we can’t do it in the real Reeves Corner, well maybe we can do it on the replica.”

I’m amazed by Perretta’s ability to turn an exhibition about stasis into a site for hope. He lived through the momentary possibility of change that the riots constituted — he has the BlackBerry to prove it — and then through the distinct lack of change that followed them. He returned to Reeves Corner, not once but many times, to see how it had become a grave for that possibility. And yet he remains optimistic. Why? Because, by simply continuing to live, to resist and to do whatever’s possible to mitigate state violence, he has been able to carry on a campaign of resistance. “We’re still here to fill the gaps that the state won’t,” he tells me, in slight disbelief, “we’re still fucking here man, the government hasn’t killed us all off.”

Written by Phin Jennings

Please note that the exhibition is free to attend.

Details can be found HERE for the Landing Page and HERE for the Live Programme.

For the Future Artists Programme click HERE.