The postal service has been busier than ever during the long months of lockdown. Letter writing might feel archaic when emails offer instantaneous contact, but a hand-sealed envelope reintroduces an important physicality that we lack in the digital age. As millions around the world find themselves isolated at home, the surprise arrival of a parcel or letter can bring welcome respite to otherwise monotonous days, as well as forming an important reminder of human connection.

With galleries and museums closed, artists and curators have been forced to get creative when it come to sharing their work. Many galleries have chosen to move exhibitions online, but have found it challenging to make an impact in the already cacophonous digital realm. Others have gone quiet, patiently waiting until ordinary life can be resumed. Some have taken a different path, turning instead to the postal system as a means of more intimate distribution.

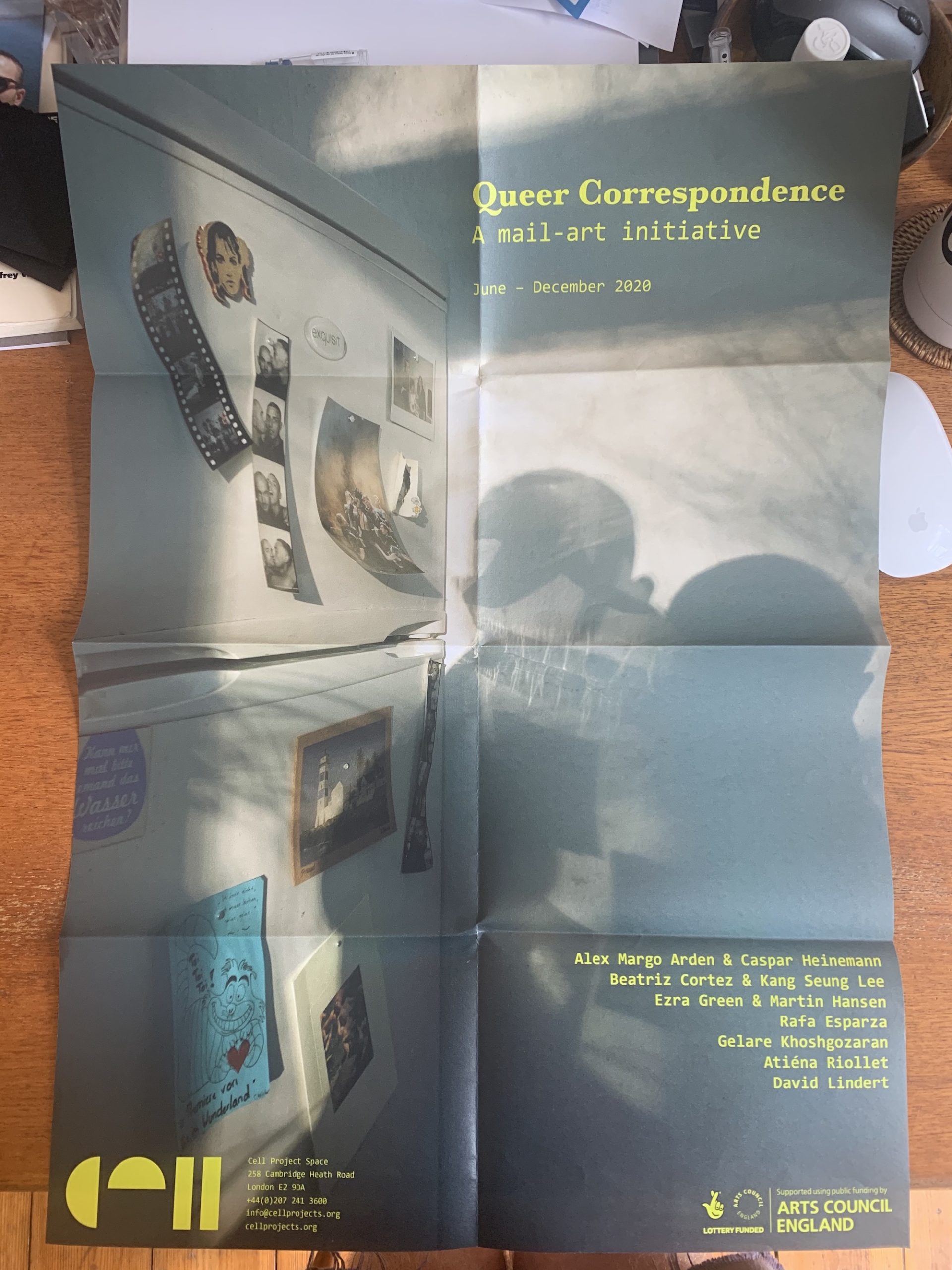

Queer Correspondence was established last month by Cell Project Space, in direct response to the closures brought about by the pandemic. In the face of ongoing uncertainty, the London-based gallery was forced to confront not just a new reality, but also reckon with the conditions that, for some, have been a reality for years.

“Not everyone has the ability to come and see shows, but the pandemic has highlighted the precariousness of certain ways of being,” associate curator Eliel Jones, who devised the project, explains. “The queer community, in a broad sense, has already been living in strange times and under strange conditions. The pandemic makes it more visible to other people, but I think the conditions were there from the beginning.”

“Letter writing might feel archaic, but a hand-sealed envelope reintroduces an important physicality that we lack in the digital age”

The project will see monthly commissions, between June and December this year, from artists and writers who originally had shows planned at the gallery for later this year. Now, they have been invited to enter into dialogue with one another remotely. The result of each correspondence will take the form of an artwork that can fit inside a C5-sized envelope. 500 of these will then be mailed to an international list of subscribers, completely free of charge.

“We wanted to create something that would nurture the conditions of the pandemic, rather than get rid of them or ignore them,” Jones says. “How can we reshape our programme, and rethink the ways in which we reach out to audiences or stay connected, at a time when we can’t welcome people or connect to even our most close of friends or family?”

Loneliness is an important concern under lockdown, with more than a quarter of adults in the UK reporting feelings of isolation since March. Art by Post, devised by London’s Southbank Centre, sets out to address these issues. It brings free poetry and visual art activities to those who have been most isolated under social distancing measures. The initiative circulates creative booklets by post, which are designed for older adults living with dementia and other chronic health conditions. “We needed to very quickly offer a creative lifeline,” Alexandra Brierley, Southbank Centre’s director of creative learning, tells me.

Brierley explains that Art by Post builds upon a previous outreach programme named (B)old, where participants would visit the gallery in person. The gallery’s initial target for the postal scheme 600 adults, but it has grown over three months to more than 1700 subscribers. To date they have commissioned four booklets, featuring activities that can be done easily from home. “We’re not expecting them to have fancy art supplies in their home. It’s about everyday household items and other materials that can be used for creative activities.”

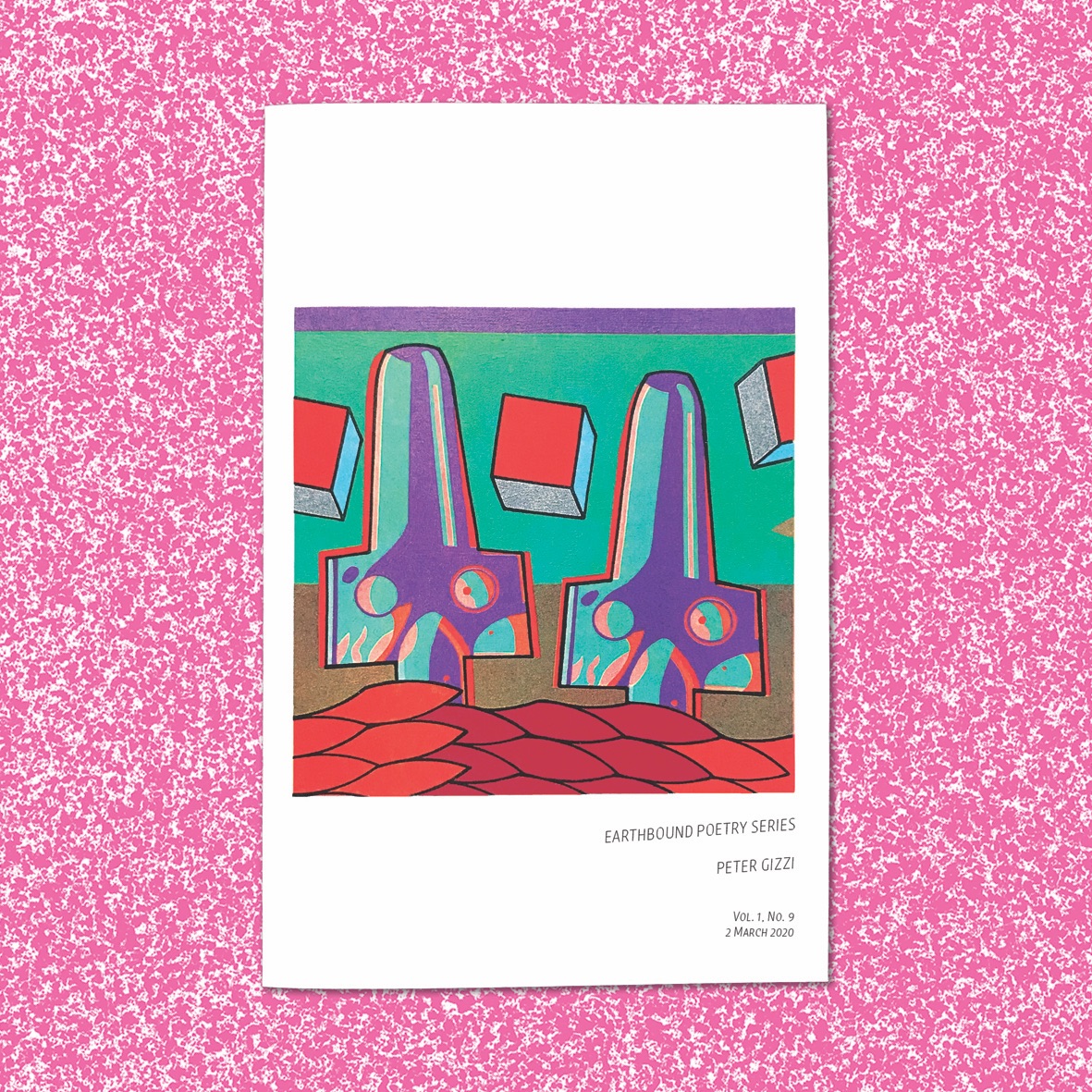

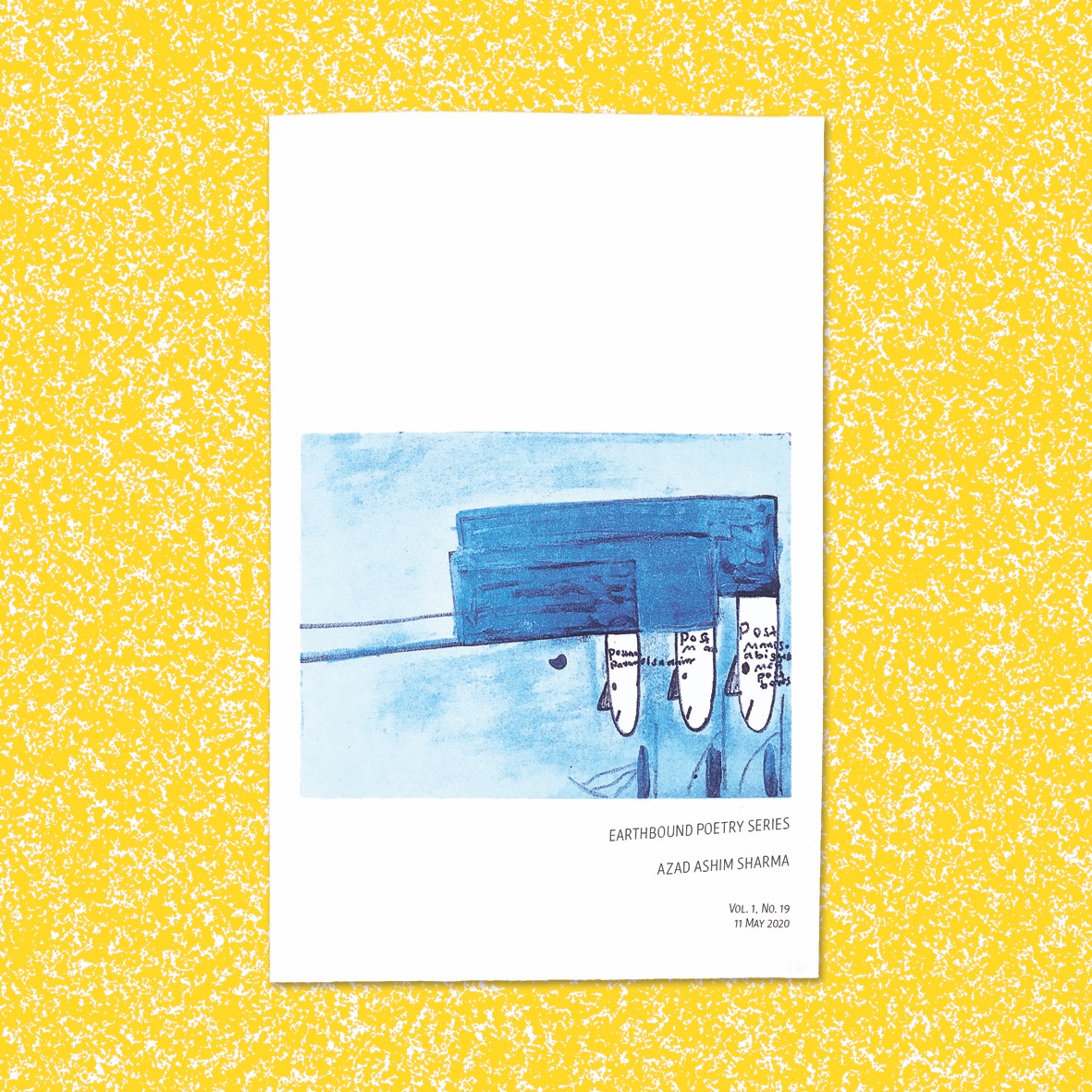

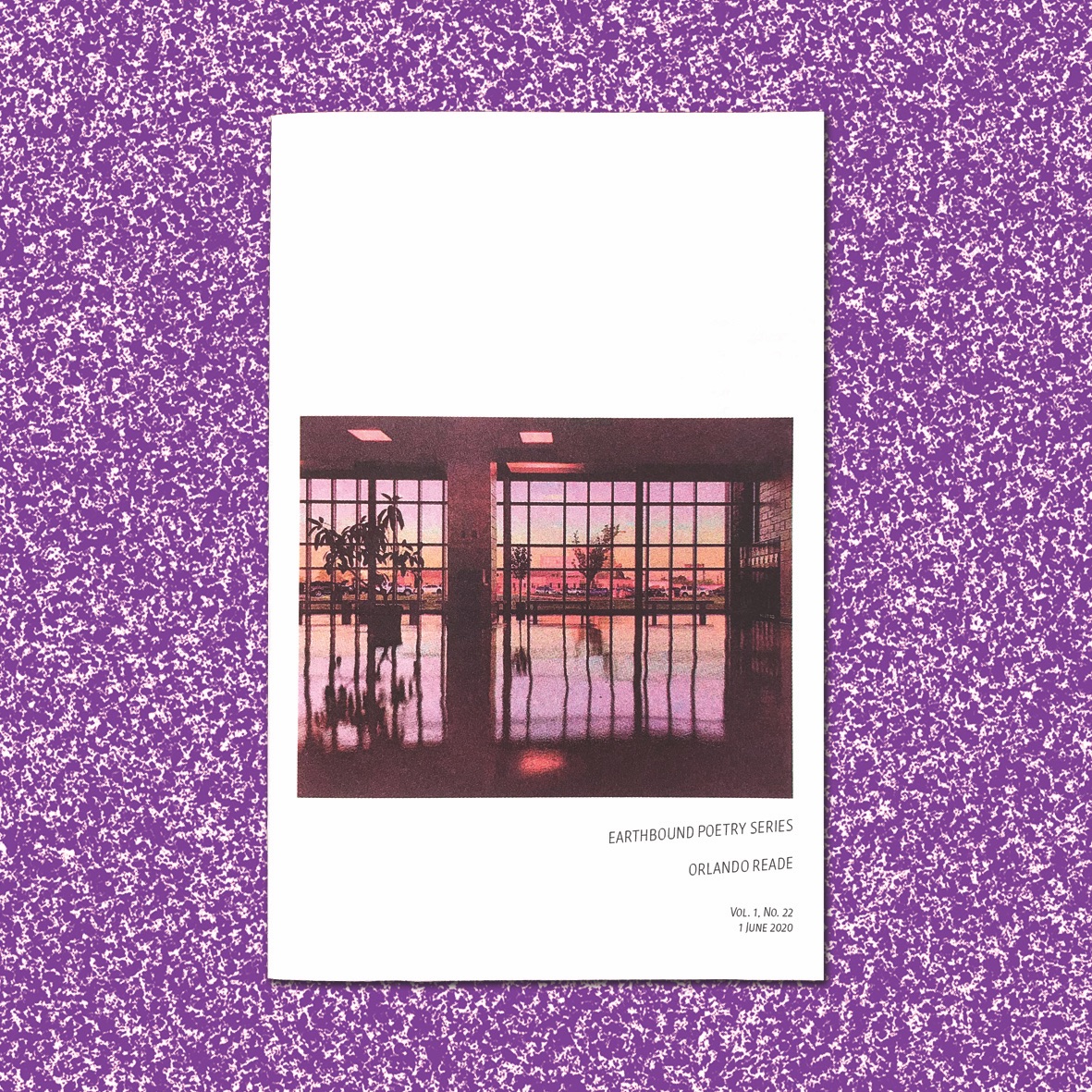

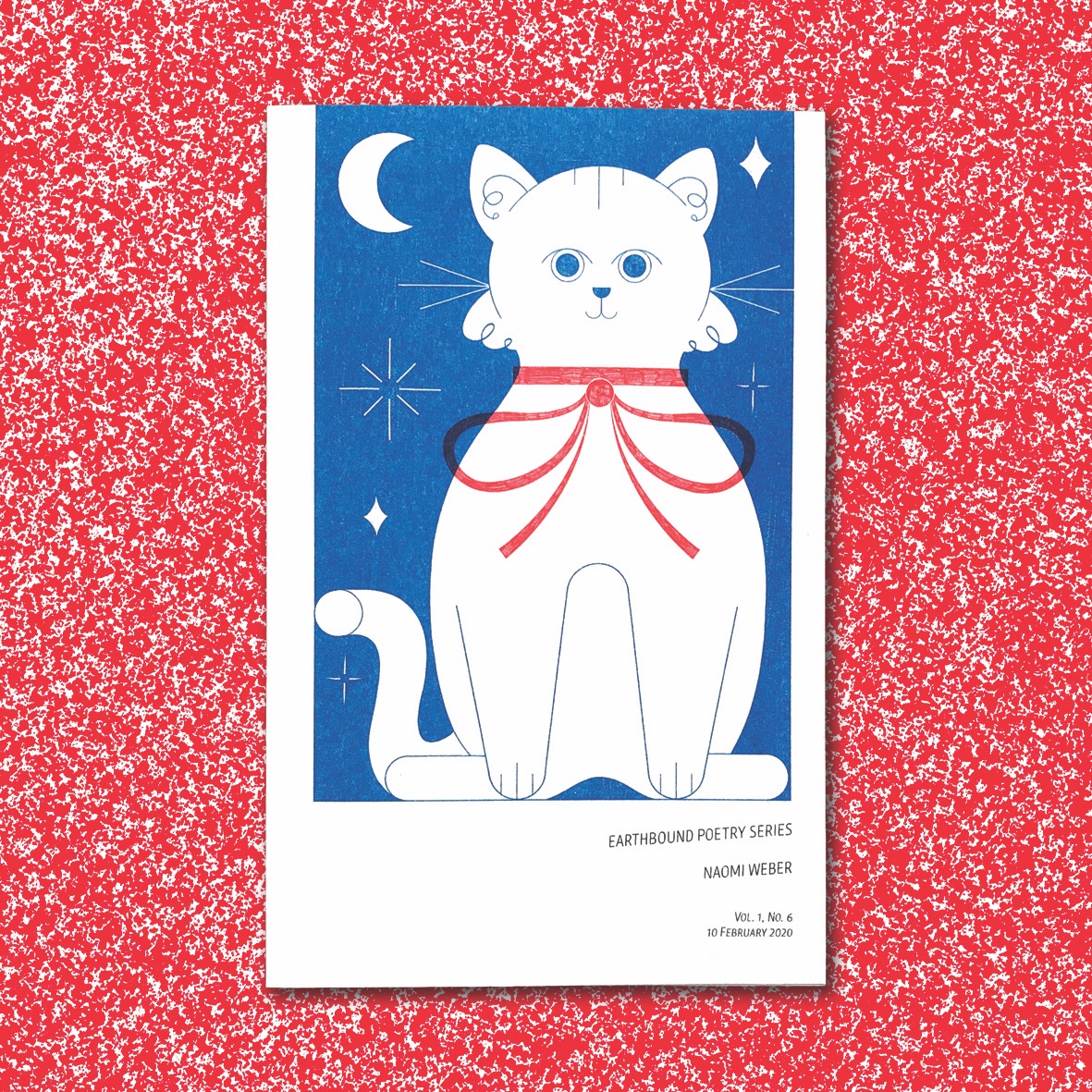

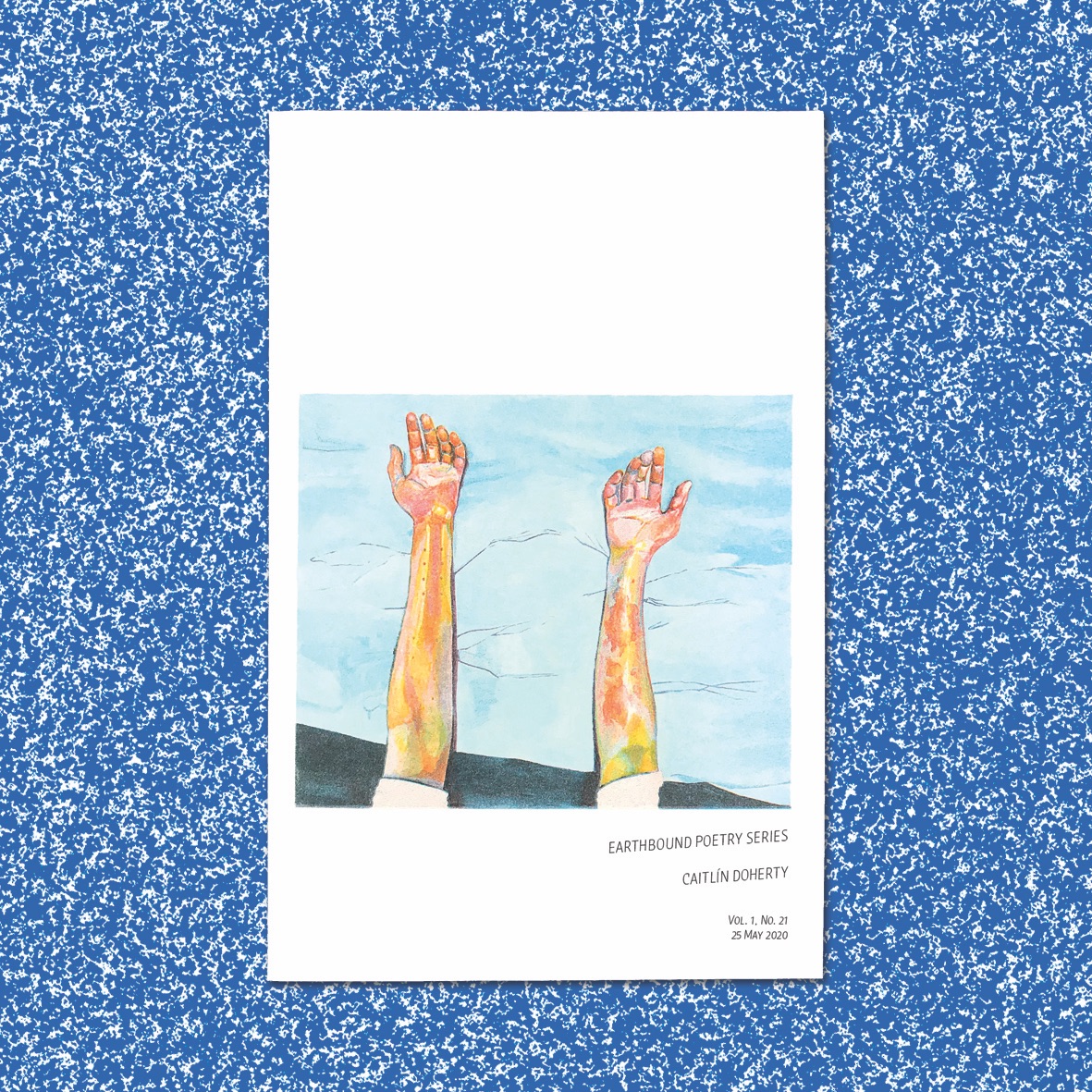

- Courtesy Earthbound Poetry Series

“We wanted to create something that would nurture the conditions of the pandemic, rather than get rid of them or ignore them”

A similarly homegrown approach is taken by the Earthbound Poetry Series, which uses the postal system to distribute riso-printed poetry pamphlets on a weekly basis. Co-founders Antonia Stringer and Ian Heames operate out of a small garage space, which they have been able to access throughout lockdown. The series has published work from poetry luminaries like J.H. Prynne and Peter Gizzi, former Sonic Youth frontman Thurston Moore, and younger talent such as Helen Charman and Nisha Ramayya.

Established in London just a month before Covid-19 became a global reality, the project has taken on new resonance in the age of social distancing. “Lots of readers of contemporary poetry would probably agree that there’s tonnes of great and diverse work being written right now, but also that a lot of it is quite hard to find,” they reflect. “We wanted to find a way of showcasing some of this new work and sharing it with a wider audience.”

A new edition is released every Monday for £2.50; 52 copies are printed to echo the number of weeks in a year, a limited run that can be repeated when an edition sells out. A monthly subscription is available, which delivers each pamphlet direct to your door. “We started with the idea of a single A3 sheet, cut down and folded to make an eight-page A5 riso booklet. The format needed to be easily repeatable, but also flexible enough to respond to the needs of different artwork and texts,” Stringer and Heames explain.

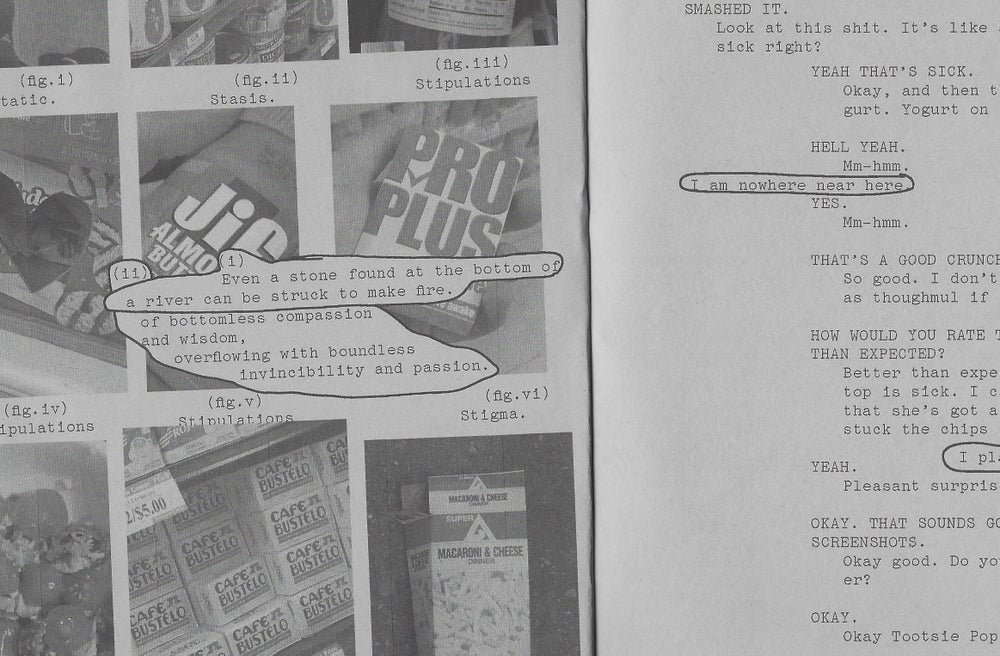

As the pair point out, poetry weeklies are not completely unheard of. The late Tom Raworth’s Infolio, which ran from 1986 to 1991, originally appeared daily, before going weekly and then fortnightly. It was, in turn, itself based on Claude Royet-Journoud’s French mag L’In-plano. Wallace Berman’s mail art publication Semina was published from 1955 to 1964, and featured letterpress text printed on an assemblage of coloured paper, photos and found material, featuring everyone from Jean Cocteau to Charles Bukowski and William Burroughs.

Mail art is frequently attributed to pop artist Ray Johnson, but there are countless examples over the course of the last eighty years. Often seen as a precedent to internet art, the two share similar principles with their aim to make art democratic beyond the institution of the museum or gallery. Mail art, like internet art, has the power to reach audiences in the intimacy and domesticity of their own spaces.

“I am a super fan of mail art, and I had always dreamed of the possibility of producing a project,” Jones, the curator behind Queer Correspondences, says. “I never felt that I could do it without it just feeling nostalgic. It’s an incredible form and a meaningful practice, but I never thought I would have a moment in time when it would feel relevant to produce one. And then lockdown happened and it felt like, if not now, when?” He explains that an important inspiration for the project was Les Petites Bon-bons, a queer artist collective from Milwaukee that grew out of the international mail art movement and the gay activist scene of the early 1970s, who drew on the city’s glam-rock culture as part of their practice.

“I never thought I would have a moment in time when it would feel relevant to produce mail art”

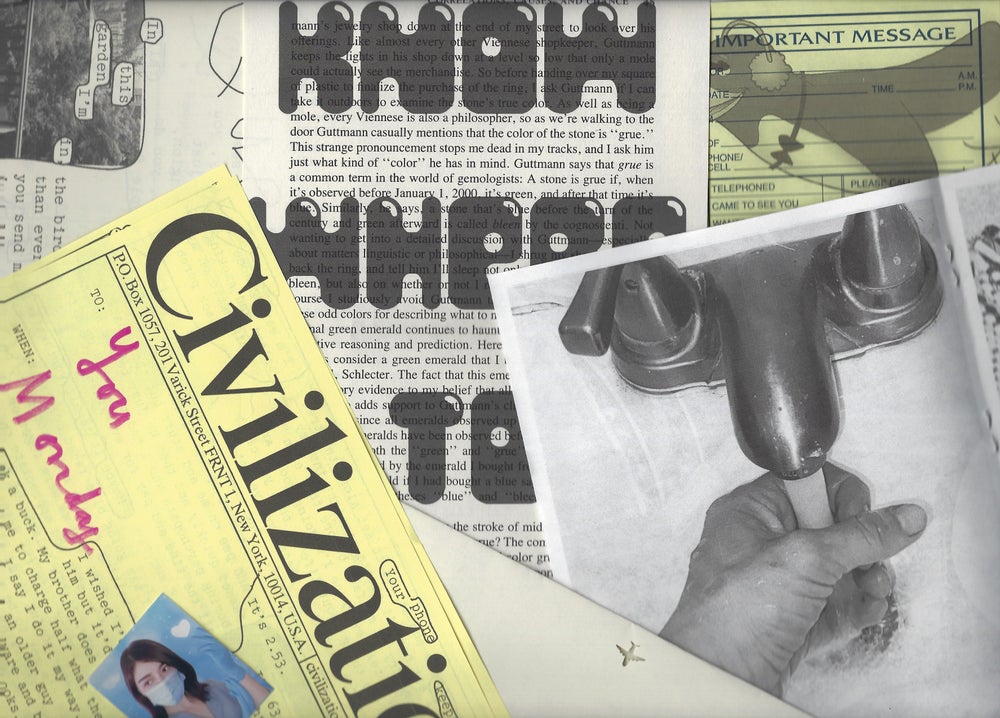

Another recent mail art project sees Civilization, a New York-based zine designed by artist Lucas Mascatello and designer Richard Turley, send out personalized letters for $3 during lockdown. Overlaid with images, text and various collaged items, the concept takes direct inspiration from Ray Johnson. “It seems like the mail is only for garbage and news—bills, government information, the occasional card or invitation. It’s really exciting to get something special, a letter or anything,” co-founder Mascatello told The Guardian last month. “I think in our time that alone is a pretty artistic gesture.”

For all of these projects, old and new, there is a line of human connection that they draw between artists and audiences, and between sender and recipient. There is an evocative thrill to an unopened envelope, sealed with the saliva of a stranger, with a handwritten address. As Snapchat messages and Instagram Stories disappear overnight, and unread emails mount up in our inboxes, the counter-impulse towards posterity lingers on in the digital age. At a time when we have never been further apart from one another, there is renewed value to be found in the indelible pleasures of ink, paper and a postal stamp.