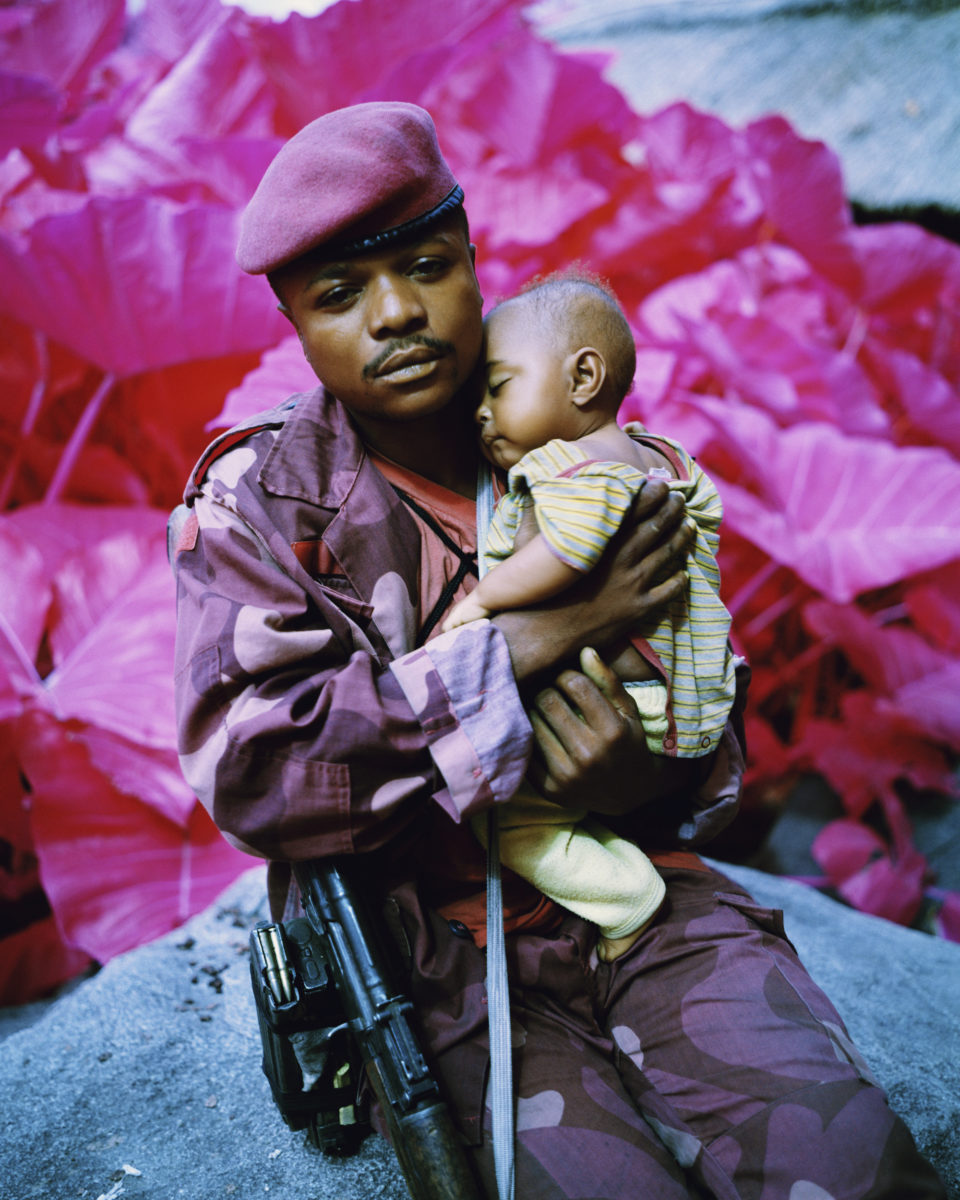

A searing pink landscape is not the sight that you might expect from a country torn apart by civil war. 5.4 million people have died as a result of the conflict in The Democratic Republic of Congo since 1998, a figure so immensely outsize that it becomes impossible to imagine. While the war officially ended in 2003, bitter tensions have remained in the east of the region ever since. Irish photojournalist and artist Richard Mosse first visited the country in 2010 for a photography series that he named Infra, after the recently discontinued Kodak infrared film that he chose to shoot his surroundings.

The results are a raspberry ripple of pink and magenta, like a spilled beetroot soup magnified a thousand times. It is unnerving and surreal; a saccharine special effect that serves to highlight an altogether more sinister reality. The aerochrome film used by Mosse was originally intended to identify the potential targets for aerial bombs, detecting a spectrum of light not visible to the human eye. Taken up anew by Mosse, the outdated military technology overlays a contemporary conflict that remains unresolved, connecting the past and present of wartime in otherworldly dissonance.

With any photojournalism or artwork created around the horrors of war, there is the danger of aestheticization; of beauty being found where there is none. Mosse confronts this with the psychedelic realm that he constructs in shades of scarlet, twisting his documentation beyond any veneer of the real and into the imaginary. It makes uncomfortable viewing, but raises important questions about the nature of war, journalism and the practice of art.

“Mosse constructs a psychedelic realm in shades of scarlet, twisting his documentation beyond any veneer of the real and into the imaginary”

Just as a picture can never convey the reality of its making, so does Mosse divorce his image-making entirely from its source. “It’s almost like self-loathing, because there’s something predatory about the camera lens,” Mosse told the British Journal of Photography in 2017. “I can’t escape photography but, whichever way you look at it, documentary photography is as constructed a way of seeing the world as anything else.”

Mosse returned to the Congo to create a second work, The Enclave, presented in 2013 at the Irish Pavilion at the 55th Venice Biennale. This time, he documented the landscape on 16mm film, using the same infrared technology to infuse his subjects with deep purples and pinks. The camera film took over two years to locate, and was eventually sourced from a failed former film shoot in Death Valley. A collaboration with cinematographer Trevor Tweeten and sound designer Ben Frost, it takes a slow-moving journey through the human side of a war-torn environment.

Presented as a multi-screen installation, the film moves easily between disorientating perspectives, as if to emphasise Mosse’s distrust of his own medium when it comes to truth-telling. Fragmented into moments of birth, life and death, of extremity and normality, it reveals the fragility of what we know as real and certain. Instead, tragedy is distorted into many forms, tinted pink and broken apart.

Mosse’s Congo refuses to conform to the traditional tropes of empathy and stoicism that haunt wartime imagery. It is heretic in its melding together of a feminized colour with a masculine scene of war, and of apparent whimsy with horror. But when we find it difficult to comprehend the deaths of 5 million people, numbed as we are to huge-scale loss, it can take an impossible image to finally break us beyond the fug of unseeing.

All images courtesy Jack Shainman Gallery and the artist