Writer Auttrianna Ward speaks to artists Naudline Pierre and Caitlin Cherry about their large-scale public art projects at this year’s Palm Heights Grand Cayman Carnival.

In the land of ‘Milk and Honey,’ artists Naudline Pierre and Caitlin Cherry create a space for Black women to escape into play. At this year’s Palm Heights Grand Cayman Carnival, curator Zoe Lukov brought Pierre and Cherry together for a large-scale immersive public art experience and celebration. I spoke with the women about the significance of play, leisure, and sensuality in their practice and the contemporary art space.

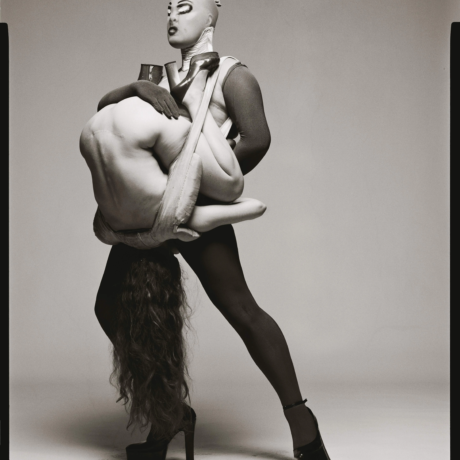

Pierre infuses an element of play into her practice, creating a utopian vision where her characters thrive despite any outside gaze. Her watercolour-like oil paintings mirror the porous nature of her practice. Cherry builds upon our archives by portraying Black women in moments of leisure and play, pushing the boundaries of how and where we are seen. This event, merging visual art with community and revelry, provided a space for exploring these concepts. Through our conversations, I delved into their processes and perspectives on Carnival, femininity and expression.

AW: I wanted to talk about this project, specifically how you became connected to it, and what it meant for you.

NP: Yeah. Well, I became connected to the project through Zoe. We had met and vibed just like, as people. We talked about her projects, what she was doing, and what was coming up. She mentioned that Carnival was something in the future she could see my work fitting into, especially in a large-scale physical interpretation. We kept in touch, talked about it, and eventually, I agreed to do it. That’s how we started. I was excited. I visited Palm Heights last summer to get a feel for the space. Despite it being a luxury hotel, something about being on that land and connecting with the water felt special. I knew I wanted to come back and create something different than what I’m used to making, which is mostly work that goes into the gallery and museum setting. That’s pretty much how it started.

AW: So, what did it feel like to work outside of the gallery space, in a more temporary space?

NP: It was an opportunity to play and add spontaneity and a loose experience to the work, making it less serious. It was a moment to let loose and let these characters enjoy the revelry in a physical sense. It felt like all these paintings that were shown in the white wall context were now on the street, with people, drinks, music, and embracing imperfection. It added an element of play to my practice and offered a new way to see the work in a moving, chapel-like building on wheels where people could spend time and have a good time.

AW: What’s your relationship to Carnival in general?

NP: I am of [Haitian] Caribbean descent, but I never really interacted with Carnival. This was my first time. I know what it is, I’ve seen pictures, and friends have gone, but I had never participated. It was a nice way to connect my work and life in a space where, although I’m not from that specific Caribbean culture, I still felt a closeness to the event, the people, and the beauty. There’s a lot of overlap, and it was nice to be a part of that.

AW: So, the characters—do you consider the figures in your work to be characters? Is that a word you use in general, or was it more specific to this project?

NP: I do call them characters. I have many names for them, and they engage in the concept of multiplicity, being one thing one day and another thing another day. To me, that represents freedom. For this project, calling them characters felt right. Sometimes, I call them celestial beings or supporting characters. Having them in the mix where people could touch and be with them made them feel like characters in the procession, so I think that’s a good way to describe them.

AW: This idea of multiplicity representing freedom makes me think about Black women, sexuality, and the lens that’s placed on Carnival. Carnival started as a very spiritual thing—it’s always been a spiritual practice, a spiritual time. But there’s also this outsider gaze that sometimes imposes an idea of hypersexuality onto it. How do you navigate portraying the female form and thinking about sexuality and freedom in your work?

NP: Well, for this project, I didn’t make new paintings for this project; we used existing ones from the last few years. It aligned with what I already do—creating a utopian world of femme characters that live in spite of the gaze. I didn’t feel the need to address it explicitly. For me, it was about giving these characters agency to be part of movement, celebration, sacrifice, and revelry. It was about them having an experience outside of an academic or commercial context.

AW: Do you think that there’s an element of Carnival and play in your work prior to this project?

NP: I see myself as a sponge. My work is a collection of many aspects of my life, consciously or unconsciously. While I never specifically thought about Carnival while making my work, elements like togetherness, body movement, form, protection, and colour overlap. Without literally going there, it applies to the form, body, and otherworldly nature of the characters in my work. Carnival allows transformation, which is a big part of my work.

AW: In what way is transforming a part of your work?

NP: Transformation is a main pillar of my work. The characters I paint are always in a state of change—getting bigger or smaller, creating fire, developing wings, and learning to fly. It’s about being one thing, moving and changing into something else, and having the freedom to become something else.

AW: Does your Caribbean heritage, specifically Haitian heritage, influence your understanding of fantasy and the fantastical in your work?

NP: It plays a huge part in who I am, how I was raised, and all the elements that make me me. This inevitably trickles into my work. I can tie my work to various sources—art historical, folklore—but I like the freedom to create and see what emerges, what wants to be seen, and what remains hidden.

AW: I think about that too in the context of Carnival’s history—how it involved hiding in plain sight throughout the Caribbean, including through syncretism. There’s an interesting overlap between your work and this idea of Carnival. I wanted to ask about the title “Milk and Honey” and the space and place you create in your work. What does “Milk and Honey” mean to you?

NP: I think themes in my work often involve the idea of an altar or an altarpiece. And with that, the theme of sacrifice or bringing something there to receive something. When I think about the phrase ‘Milk and Honey,’ I think of it as some sort of reward or gift, often for a sacrifice or an acknowledgment of change. It’s about coming to a place to be transformed and to receive something. I wanted to connect the themes of sacrifice and revelry—how they often come together. You have to feel pain to understand joy, and these things are intertwined. When the body moves, and there’s music, there’s a transcendence from the mundane. ‘Milk and Honey’ makes me think of fantasy, beauty, liquids, and sensuality. We created a bar where people could come and get sustenance, but the float itself was a place where you could sacrifice your stress and receive a different part of your personality or history and carry down the road with that. It was about celebrating celebration, agency, and the body being free.

AW: So, when you build these altars, both in your work in general and for this project, what do you, as the person building the altar and coming to it, hope to receive?

NP: So that’s a big, deep question. There are a lot of things I hope to receive. Always life. Inspiration, understanding and escape.

AW: Escape from?

NP: From reality. I think the most important thing and one of the most important means for survival is imagination. Imagining what could be keeps you going, keeps you alive, gives you hope, and allows you to endure. So, the fantasy of these characters in this imagined world is really important to me.

AW: As a Caribbean art researcher, I’m constantly thinking about the theme of water. And something that’s really come to the forefront in this conversation is the feminised connection between water, sensuality, and movement, which is so present in your work. How do you connect water, sensuality, and sexuality in your work?

NP: Yeah, I think my work allows me to portray the elements, mainly fire, but sometimes steam and water, in a space where the rules we abide by here, like gravity, don’t matter. The elements can still exist, and often, the flames will feel like water, or the water will feel like flames. The act of painting itself is sensual. There’s an interaction between myself and the characters, where they almost tell me what they want me to make or how they want to show up on the canvas. There’s a synchronicity and sensuality to that. It’s very much a part of the work in the making and in the entering and understanding of it.

AW: And I think as Black women, our sexuality and sensuality are often oversexualized, so we sometimes feel the need to protect ourselves and our bodies. How do you open yourself up to comfortably talking about sexuality and sensuality in your work? Or is your work a way to present that outside of yourself?

NP: I think my work is a way to present it outside of myself and sort of remove myself from the conversation. I don’t look to say anything with my work; I’m processing my experience, healing myself, and hopefully healing others. All of that is kind of underneath the surface. I’m looking for a sense of understanding beyond language, mostly through texture, colour, and visual themes. So I wouldn’t say that I’m super, super comfortable. Maybe this allows me to address those things without directly addressing them. I struggle sometimes with my own perception of myself and my body and how it exists in the world. And I think making these works helps me work some of that out.

AW: Yeah. Do you think that ‘Milk and Honey’ helped you process that as well?

NP: I do think that there was a sense of freedom in both the fabrication of the project and the experience itself. We had major setbacks, like a big storm, but I just kept going, thinking, “I’m just gonna keep walking down this road and [dancing].” That helped me release some of the control that’s such a big part of how I make my work and who I am when I make it. It was nice to let go of some of that.

The costumes and seeing all the beautiful bodies on the street, especially those that uplift my own, were a really special experience. I remember feeling a certain sense of joy at seeing Black bodies and feeling like I was in heaven. I could let my body be free instead of trying to tame it. It was liberating to just let it be free on the road.

AW: Is there anything else you want people to know about this project or Carnival and the work in general?

NP: I think the main thing is what we discussed—celebrating the beauty of existence, a collective joy, as a sacrifice to receive more life, beauty, and healing. It’s like a balm. Incorporating that into life, not just during Carnival, is really important, especially for Black bodies to allow ourselves pleasure, joy, and letting go. There’s a lot of editing and being in the world while also being aware of other people’s historical and cultural lenses, which can feel really constricting. I think it’s important to have spaces where our bodies can be free, experience pleasure and joy, and have fun.

AW: And did you get to achieve that yourself through this?

NP: I did. I did. And it was really special.

AW: What was the process like for creating the work that you made for ‘Milk and Honey’?

CC: We decided to use images of paintings I had previously created. Within the past few years of my practice, I’ve been representing Black women within not just popular culture but also nightlife, which I feel intersects well with the idea of Carnival. So, it was mostly about how to make those images work with the format of a parade float or Carnival truck, which is a new context.

AW: One of the first works I saw of yours was your City Girls painting. I remember I had never seen Black girls who looked like that in this context—girls that I know, the way they dress, the way they stand, the way you reflect them. I hadn’t really seen that in painting. That was one of the really cool things. Because even though they are celebrities, your work speaks to the margins of how Black women are supposed to be represented publicly.

CC: Yeah, for sure. If you’re witnessing popular culture and know anything about hip hop/rap, or just music generally, you’re very familiar with the rise of Black female rap—a new era. And so, it’s interesting just to have that be such at the top in one context. But I think, for me, the reason why I started wanting to bring that into the realm of fine art/painting is that I always foresee how popular culture, particularly Black popular culture and femininity, gets even more precarious.

And then, you know, we could talk more. I talk more about the margins of that, which is even more precarious. It’s like, that sort of culture gets very boosted up; it’s the trendy thing. It sets off all these other trends that reverberate outside of Black popular culture, maybe even gets into white culture, maybe gets into international hip hop scenes and rap scenes, and affects aesthetics on almost every stratosphere of beauty culture—what’s popular in terms of body types and how people represent themselves and their wealth, or maybe being the antithesis of that in some sort of way because I think white popular culture always has a reaction that tries to run away from what we start to accept.

But yeah, I wanted to start archiving this within a medium revered for cultural archiving in Western popular culture. It can catalogue culture effectively. I realised that this culture—especially Black femininity in the fast-moving music industry—is fleeting and hard to capture. We’re not even touching on marginal types of Blackness, making it challenging to archive our history. When I address the fringe or extreme expressions of how these women present their sexuality and dress—so unique and radical to our history—it leads us into new types of feminism, like sex-positive feminism. This new era of feminism is complex and hard to describe fully.

So, I use my practice to start to archive that as well.

Because once we see that within the context of, not just the commercial gallery, but within the fine art realm generally, it’s put out of context but also given the status it deserves because we’re talking about our culture; we usually never agree on what the best representation of ourselves as Black people is. But as someone who loves these aspects of our culture, our sexuality, and how Black women present their specific aesthetics and what we do with our hair and bodies—that’s just what we do; we live it. And I want it to be revered and stored.

And I want it to be seen as valuable, just to the same level as all other aspects of our culture. We’ve had many eras of conversations and debates about respectability politics, which is very important to my practice. I like to throw that debate into the air because hypersexual representation is always difficult to justify when you add in the Black body. We often have to consider how we want to present ourselves and what aspects of Blackness we show to others.

[But] I just really don’t think we have anything to prove. We don’t have anything to prove to anyone about what our culture is, and it’s going to be all of it. All of it is perfect to me. I will represent the aspects of our culture that are the most interesting and aesthetically pleasing to me. And that just happens to include the moment you’re talking about—the City Girls moment.

AW: I mean, I think you’re amending this idea of who deserves to be archived. Right?

CC: Yeah.

AW: Because so much of Black popular culture is demeaned, right? Even among ourselves, we grapple with who we want to represent us and what’s considered respectable. These are years-old conversations about respectability politics. But you, Caitlin, you’re pushing the boundaries of what we think should be archived. Contemporarily, there’s a significant push to highlight Black leisure. You go to the museum and see these classy photos from the 1950s— which is seen as an acceptable representation. But then there are the other women who might head to Miami for the weekend currently; they look like the women in your paintings. I’ve looked like that at points in my life, too. It’s a rich conversation about leisure, play, and who gets to engage in it within our culture, how you’re dressed during it, and how it’s all tied to sexuality as a Black woman. It’s a fascinating discussion that’s very relevant to Carnival and beyond.

CC: I won’t discuss the leisure moment as just a trend within Black art, but it is necessary for Black representation. Due to the history of art having such limited representations of all aspects of Black culture, it makes sense that representing ourselves at leisure is still radical. There are artists, theorists, and academics discussing the radical reality of rest, and I think that’s a necessary next step.

However, to me, this is very soft. Yes, we do rest, but it’s about more than that for people like me, who grew up in big cities like Chicago and lived in New York. People work hard and may not have a lot of money, but they also have free time to go out and party. I think Carnival represents a unique context where leisure isn’t just about rest—it’s about celebration, looking forward to all year. So, in our leisure time, rest and play, partying are all included; it’s all part of the broader spectrum of leisure.

That’s why I became interested in representing nightlife and celebrity performances. These are the types of images I am searching for. I see it as an extreme version of leisure—more about what we do in our leisure as viewers, absorbing the culture. Whether sitting down or lying down, we watch these celebrities and then discuss what they do. This becomes a significant way in which we relate to each other.

So, leisure is included in that as well. But for me, it’s a different flavour of leisure, involving a lot of work, too, like preparing to go out in the evening or dressing up to perform. And I’m not just interested in the music—it’s more about the aesthetics and the stage settings we see at events like the BET Awards or Carnival. Even though my work involves technology, Carnival is all about being in the flesh, in the daylight, which contrasts with how we usually experience nightlife. This jarring contrast reminds me of daytime drag, where you have to be meticulous about your appearance because it’s all visible. I think this focus on preparation and presentation is why events like Black Prom and Carnival are so significant—they’re like the Olympics of cultural expression, where we meticulously plan and prepare making the dress [or costume], buying the dress, making sure we have everything set.

AW: Do you have a Caribbean background?

CC: No, my ancestry is slave descendant Black American.

AW: Mine too, primarily. I brought it up because there’s a beauty in combining you and Naudline, showcasing two different entry points to depictions of Black femininity and sensuality. It highlights how the Caribbean diaspora and the African American experience can streamline consciousness and conversation. It’s also fascinating to see Southern women reflected in your work. From my perspective, it adds a rich layer. What was your connecting point as an African American coming into this Caribbean context?

CC: Yeah, I mean, there’s always that conversation, especially when you think about the birth of hip hop or rap in the U.S., like how most of those people, especially in New York and other big cities, were always mixing and mingling. I feel like the Black diaspora, particularly those rappers with Caribbean ancestry, had their specific narratives somewhat flattened. For me, living and growing up in big cities like Chicago and New York, there’s just so much overlap between our cultures, and we have been sharing and influencing each other for a long time. Our cultures are intertwined, and while we can have nuanced conversations about our differences, I don’t really see them as very different.

But I do acknowledge that there are specific differences, country to country, that are cultural and language-based. It’s interesting to be involved in a project that might be outside my direct cultural experience, but I feel like I’m a sister to it. In artmaking, especially in fine art, we often try to set strict boundaries about who we are or how our work is perceived. Yet, I think there’s a lot of kinship between Caribbean culture and Black American culture, though there are nuances that may have us like butt heads at times.

I really enjoy participating in this, kind of as someone who has been very influenced by what Caribbean-descended people in America have brought into the Black American narrative. It’s like a two-way street. Even in places like New Orleans, which is part of our country and culture, I closely absorb and observe it, as it feels akin to mine. But yeah, I wish I could have gone and donned my first costume and all of that had the thighs out in the daytime [laughs]. I just love the idea of Carnival—whatever happens that day [or week] makes you feel balanced for the next 364 days because you get to don a character. It’s a type of escapism that I think Black people need to keep us going.

Words by Auttrianna Ward