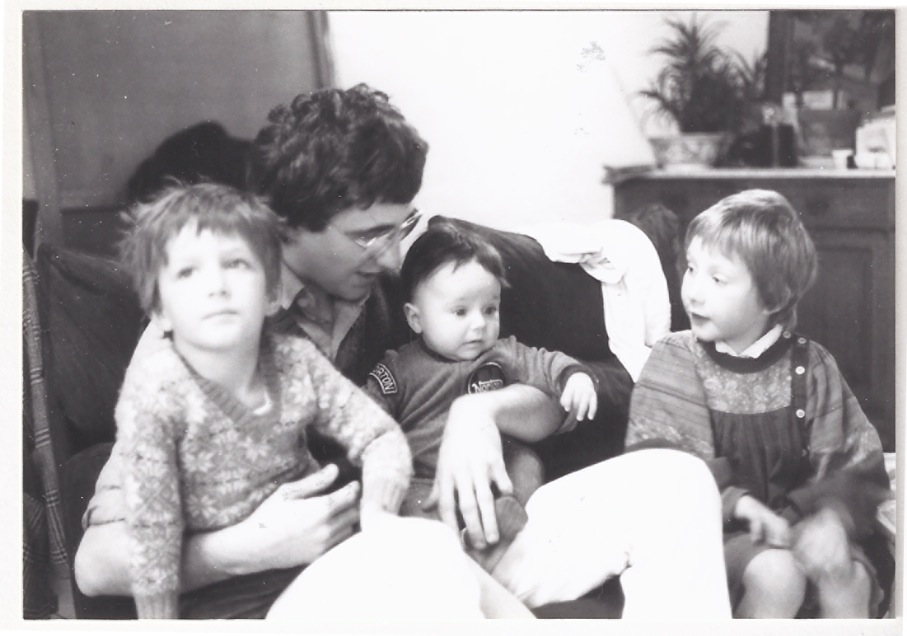

“We were very close as a family,” recalls the daughter of Belgian artist Philippe Vandenberg, Hélène. She smiles: “When we all used to turn up at an opening with my father, my two brothers and I, in our black coats, it was like something out of The Godfather: ‘Here come theVandenbergs!’” In the immediate aftermath of Vandenberg’s suicide in 2009, the clan remained tight-knit, and the siblings, Hélène, Guillaume and MoVandenberghe (the original spelling of the family name, which the artist altered in order to distance himself from his own father), decided to take charge of his estate. “It wasn’t easy,” says Hélène.“Wehadtocreateourown legitimacy, fight for it, but none of us questioned the decision.

Vandenberg’s children grew up immersed in their father’s artistic endeavour. Hélène and Guillaume, the children of the artist’s first wife, spent alternate weekends with him when they were small; Hélène later lived in the same building as her father in Brussels until the end of his life.Youngest sibling Mo lived with his father in his Ghent studio for a large part of his teenage years, surrounded by paintings and the smell of turpentine. “It was intense,” he says soberly. “I saw all the images he was painting. But we never spoke about his paintings. What he needed from me was the rest of life: to collect me from football games and cook for me. But he was always thinking of his work.”

“He would say that he was always painting,” adds Hélène, “even when eating, sleeping or taking a shower. It was his inescapable condition. And then towards the end, as he and I were sitting in the kitchen, he asked my permission to kill himself. He was very attached to us: for him there was his work and his three children. It would have been horribly selfish to say no. He told me how exhausted and emotionally numb he felt. I said that if he really wanted to, then he was free to go.” We sit in silence digesting this, then Mo says, deadpan: “But he was also a very funny guy.” One constant source of self-deprecating humour was Vandenberg’s own sombre turn of mind. Guillaume Vandenberghe recalls how, even when his father tried to make a colourful happy drawing for his little granddaughter, “A little swastika might creep in, and he would laugh at himself.” In contrast with the love he received from his family (it is significant that ten of his ex-wives and girlfriends attended his funeral together), the art world strenuously resisted Vandenberg. After his death the artist’s children encountered some astonishingly hostile responses: a gallery owner equated their taking over the estate with “killing their father a second time”; a museum director advised them to burn eighty per cent of Vandenberg’s oeuvre. Undeterred, they focused instead on how best to manage their father’s artistic legacy. After an initial period of retreat—shutting down their father’s Brussels studio and putting a stop to all selling of his work—the siblings decided to pool their resources. Art world insider Hélène left her job as artistic advisor to the CEO of the Centre for Fine Arts (Bozar) in Brussels to devote herself full time to the estate as its general manager. Her younger brother Guillaume, a documentary filmmaker (and the author of three films about his father, two of which were made when the artist was still alive), took charge of photographing and captioning every single one of Vandenberg’s many thousands of paintings and drawings. Today every work has a complete identity card in the estate’s digital and custom-made database, which will also form the basis for a future catalogue raisonné. The siblings donated their father’s enormous archive to the University Library in Ghent: it is being catalogued by an archivist, and is also accessible to art history researchers.

Mo Vandenberghe used his own expertise as an architect to transform the studio—once chaotic and packed to the rafters with paintings and drawings—into a space fit for conservation of the works (now housed in specially designed casings, allowing them to be accessed as a proper archive) and to welcome visitors, while retaining some of the artist’s personality.“It’s a balance,” he explains. “We didn’t want anything too romantic.” “But,” adds Hélène, “we wanted people to feel that he was still there somewhere, that it was his studio and no one else’s.”

In the redesigned studio, a vast industrial space lit from above through a glass ceiling by the northern light that Vandenberg preferred, it is indeed possible to imagine the artist at work, looking, in the words of Guillaume, “like a monk—like Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev”. The artist’s table, caked with paint like a gigantic palette, is still here, as are the vitrines Vandenberg composed from family photographs and other exhibits, some—a mummied pig’s ear, a fragile Amazonian crown made of feathers—suggestive of a personal cabinet of curiosities; others, like reproductions of a Goya etching, or a famous Chinese torture photograph written about by Georges Bataille, indicative of the artist’s anguished fascination with the extensiveness of human atrocity. “The studio,” Hélène explains, “was not an empty box; it was a whole world around my father, like his second skin.”

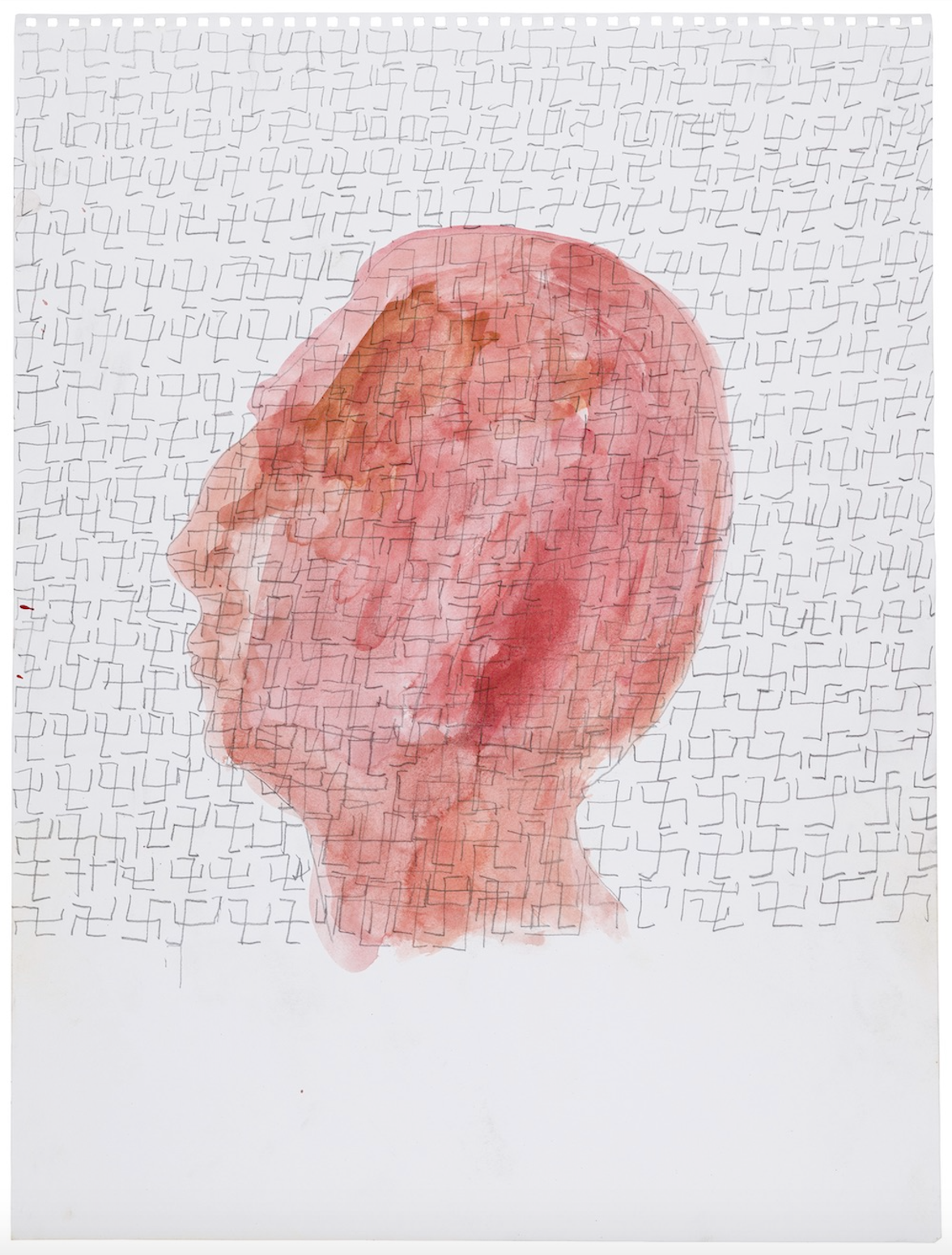

No title, c. 2003, watercolour and pencil on paper, 47.3x36cm

Nowadays the studio is the open heart of the Estate Philippe Vandenberg, and is frequently visited by art students, schoolchildren, collectors, curators and artists of all kinds. A visit will entail the projection of a film by Guillaume, in which the artist narrates his condition as an outsider and painter of exile, as well as a pictorial journey across Vandenberg’s oeuvre, expertly curated by Hélène. This begins with a remarkably accomplished portrait of Philippe’s grandfather done by the artist in his teens, spans Vandenberg’s systematic incorporation of artists such as Cézanne, Bacon or Velázquez, his obsession with religious iconography and occult symbols, his early-1980s shard paintings (made from dismembered figurative paintings) and blood paintings (featuring words drawn with the artist’s blood), and ends with some of his last works of 2008, in which meditative, textured abstract canvases are overwritten with the mantras “Kill them all” and “Il me faut tout oublier” (“I must forget everything”)—expressions, Hélène says, of her father’s utopian hope of doing away with his artistic past and starting anew. Throughout his career, Vandenberg sought how to “find light in the paint”, to tell a story, whether it was through abstraction, geometry or the figurative. “The latter,” Hélène says, “has a tendency to return, because of our important narrative painting tradition here in Belgium, the Netherlands and Germany— Bosch, Bruegel or Ensor.We are storytellers.”

One of the initial tasks undertaken by his children was to assess the quality of Philippe Vandenberg’s painterly story: gaining a more detached perspective on a beloved father’s work being a necessary stage of setting up a successful estate. “We needed to know if the work could stand up in an international context,” says Hélène. “As my father’s children, we were too close. Of course we thought his was the best work in the world.”At first, instinctively, they turned to other artists rather than to curators or collectors to confirm their appraisal of the work. Vandenberg was, in Hélène’s words, “an artists’ artist”, whose work speaks most eloquently to fellow artists such as Berlinde De Bruyckere and Dirk Braeckman, but also, for example, choreographer and dancer Meg Stuart: “They looked at his work and saw the courageous solutions he found to the struggles that everybody experiences through the creative process, how he dared to destroy so much in order to create, time and time again. That is what made him so important, and unique.”

Once they felt confident of the oeuvre’s quality, Vandenberg’s children were able to define their main goal and strategy: to keep their father’s work alive through international exposure. During his lifetime, Vandenberg had not been understood in his own country. “In Belgium,” Hélène explains, “people from the art world seem incapable of actually seeing my father’s work. I see them staring at the paintings, but they cannot see them.It’sasthoughtheirimage of him (as a ‘romantic’ painter, complex and troubled) is stand- ing between them and his work, obscuring their vision.”

This situation was further complicatedbyVandenberg’sown self-destructive inability to cope with commercial success when it did come to him in the 1990s. “My father was a very honest person,” Hélène says. “That’s why he couldn’t stand the art world: he could not play the game. He just wanted to make good work that was a mirror of society, a portrait of humanity.” This entailed much provocative political imagery, ranging from Nazi iconography, treated with harsh humour, to portraits of such controversial figures as Yasser Arafat and Ulrike Meinhof. Vandenberg explicitly identified as a “kamikaze” artist: “When things got too comfortable he had to break them up,” explains Hélène. “But from a human perspective it was unbearable: he became very lonely. He was utterly rejected by the art market and retreated into his studio.”

The labels of kamikaze, exile and of the “maudit” (forsaken) artist in the tradition of Rimbaud, Artaud and Céline are all Vandenberg’s own and therefore authentically valid, but his children have been resolute in their desire to open their father’s work to fertile new readings and interpretations. “It’s a live process,” says Hélène, “and that is how our father raised us, in a very open-minded way. We could do whatever we wanted with our lives, but we needed to do it consciously and passionately. Maybe that is why we feel so free now.” Philippe Vandenberg did not leave any instructions on how he wanted his legacy handled, besides wishing his work to remain mobile rather than enshrined in a museum-mausoleum. “We bear that in mind, while taking into account that society is always changing,” says Hélène, who also serves as an adviser to the Institute for Artists’ Estates. “We must adapt to new ways of looking at the work which even he would not have accepted. We discussed whether he would have wanted an image of his work printed on a tote bag, and we decided to do it because it’s a way of communicating the work. On the other hand when a curator wanted to dismantle a large work made up of seventeen small paintings in order to show it, we refused, on the basis that this large work is ordered and numbered and has only one title, so that you cannot divide it.”

Today the Estate Philippe Vandenberg is a flourishing enterprise with an annual budget of 70,000 euros, represented internationally by Hauser & Wirth, with a show at the gallery in New York in June. There will also be an exhibition in Antwerp in March entitled Live or Die, curated by Brigitte Kölle. The show, a dialogue between the works of Vandenberg and Bruce Nauman, is exemplary of the creative way the estate likes to work. The siblings are also planning to set up a prize for artistic courage inspired by their father.

The estate is now busy enough to employ a team of seven, but all decisions are still taken by the three siblings only. “Three is a democratic number,” Hélène declares. “What tends to happen is that I come up with a thousand ideas, Guillaume objects to most of them, and Mo finds a compromise. We have discussions and arguments but they all follow one single line of thought: we want to keep our father alive internationally. The question is always: is this helping the goal? We’re building bridges all the time: that is what keeps the work alive.”

One of Philippe Vandenberg’s founding metaphors for the human condition as he experienced it was the cage. From childhood he had felt caged and alienated, turning to drawing and painting as a means of communicating with the world beyond. In a text from 1998 he wrote: “During the final exercise, death will open the cage. I will jump out carefully onto the road and disappear into the bushes.” The artist has escaped; his legacy remains—safe, flourishing and free.

‘Philippe Vandenberg Curated by Anthony Huberman’ runs from 27 June until 29 July at Hauser & Wirth in New York. hauserwirth.com

This feature originally appeared in Issue 30