Many budding artists will recall being sworn off black paint in the classroom. Teachers might claim that a straight-out-of-the tube hue lacked nuance or depth, and could lead students to create cartoonish, graphic outlines, as opposed to exploring more subtle gradations, where muddy browns and deep purples stand in for shadows. Scientific purists might even claim that black isn’t really a colour, but rather just the absence of light.

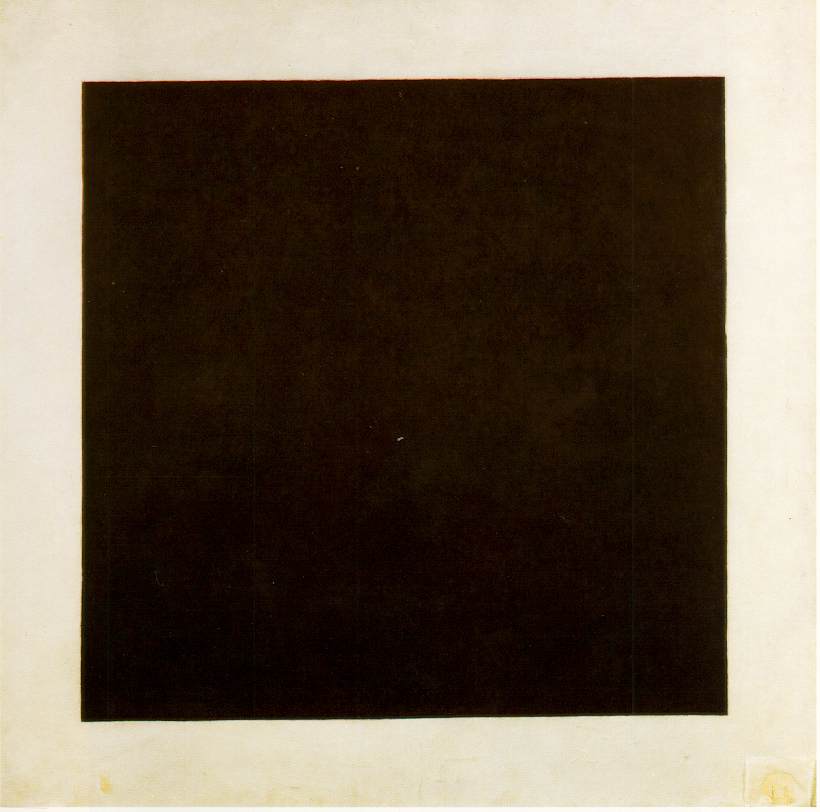

Whatever the argument, the fact remains that black pigment is a far richer and more complex substance than people often give it credit for, both in terms of its materiality and its conceptual power. For example, Kazimir Malevich confounded critics when he first presented his avant-garde Black Square in 1915, while Kerry James Marshall has spent his entire career refining a stylised and carefully mixed black to evoke a skin tone that reflects the complexities and fallacies of race. Moreover, Anish Kapoor created a stir after buying exclusive artist rights to Vantablack, which absorbs 99.965% of visible light, making it the blackest thing on earth.

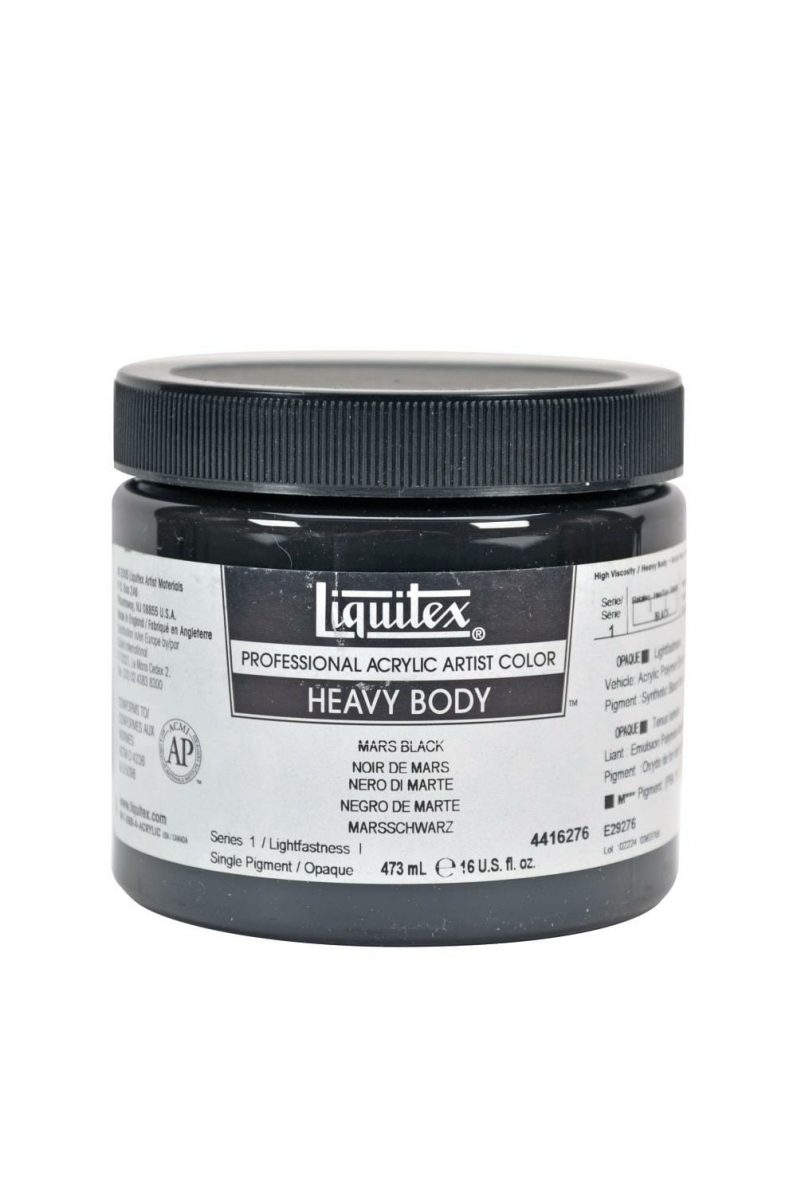

Artists other than Kapoor can find a ‘neutral’ dark pigment in Mars Black, derived from the mineral iron oxide (the name comes from the fact that Mars is considered to be the god of iron as well as war, leading alchemists to refer to the metal as Mars). This dense, opaque material has a high tinting power, is fast drying and has great permanence, making it ideal for painting vast swathes of blackness, mixing tones and underpainting.

Invented in the 20th

century, it is warmer and browner than neighbouring hues such as Ivory and Lamp, and was introduced as a far less toxic alternative to the charred bones and residual soot traditionally used to make them.