In the 1960s and 1970s, commercial printing operations didn’t want to be associated with radical literature. The result was that underground printing had a heyday. Including anarcho-Marxist outfits like the legendary Detroit Printing Co-op, set up by Fredy Perlman, a Czechoslovakian-born, Columbia-educated economist and anarchist, and Lorraine Perlman (nee Nybakken), a violinist and maths teacher.

In the 1960s and 1970s, commercial printing operations didn’t want to be associated with radical literature. The result was that underground printing had a heyday. Including anarcho-Marxist outfits like the legendary Detroit Printing Co-op, set up by Fredy Perlman, a Czechoslovakian-born, Columbia-educated economist and anarchist, and Lorraine Perlman (nee Nybakken), a violinist and maths teacher.

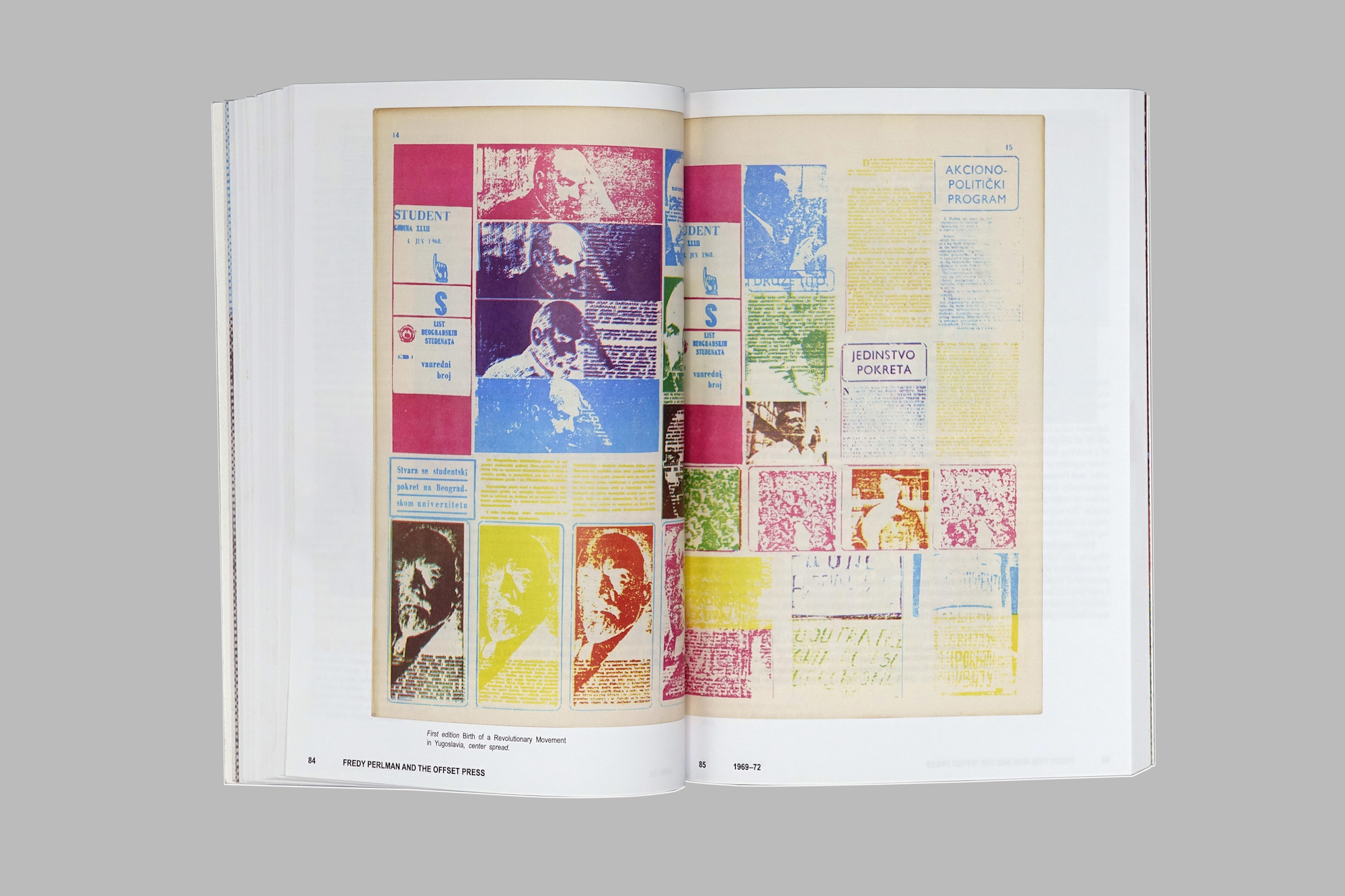

As told by Danielle Aubert in The Detroit Printing Co-op: The Politics of the Joy of Printing, Fredy Perlman travelled from Turin (where he was teaching) to witness the Paris uprisings of May 1968. There he threw himself into organisation, seeing in the manual work of producing leaflets a way to unite the roles of labourer and intellectual. He returned to Michigan and settled in Detroit, a centre of left-wing and Black political activity as well as manufacturing.

The Perlmans set up a 50-year-old Harris offset printing press opposite a Cadillac factory in the city’s southwest, working with a discounted or donated stock of unused paper from other print works. The machinery was cumbersome and dangerous to operate, but anyone was allowed to use it, provided they helped maintain it and assisted with each other’s projects.

Perlman had “never before… felt so intellectually stimulated” as when setting up the press and mastering its processes, Aubert says. He believed in the free dissemination of ideas: in 1961 he had printed 91 copies of his work, The New Freedom: Corporate Capitalism, on a mimeograph machine, and then enjoined readers to make their own copies. Had he lived beyond 1985, the early utopian, unregulated internet would surely have been his element.

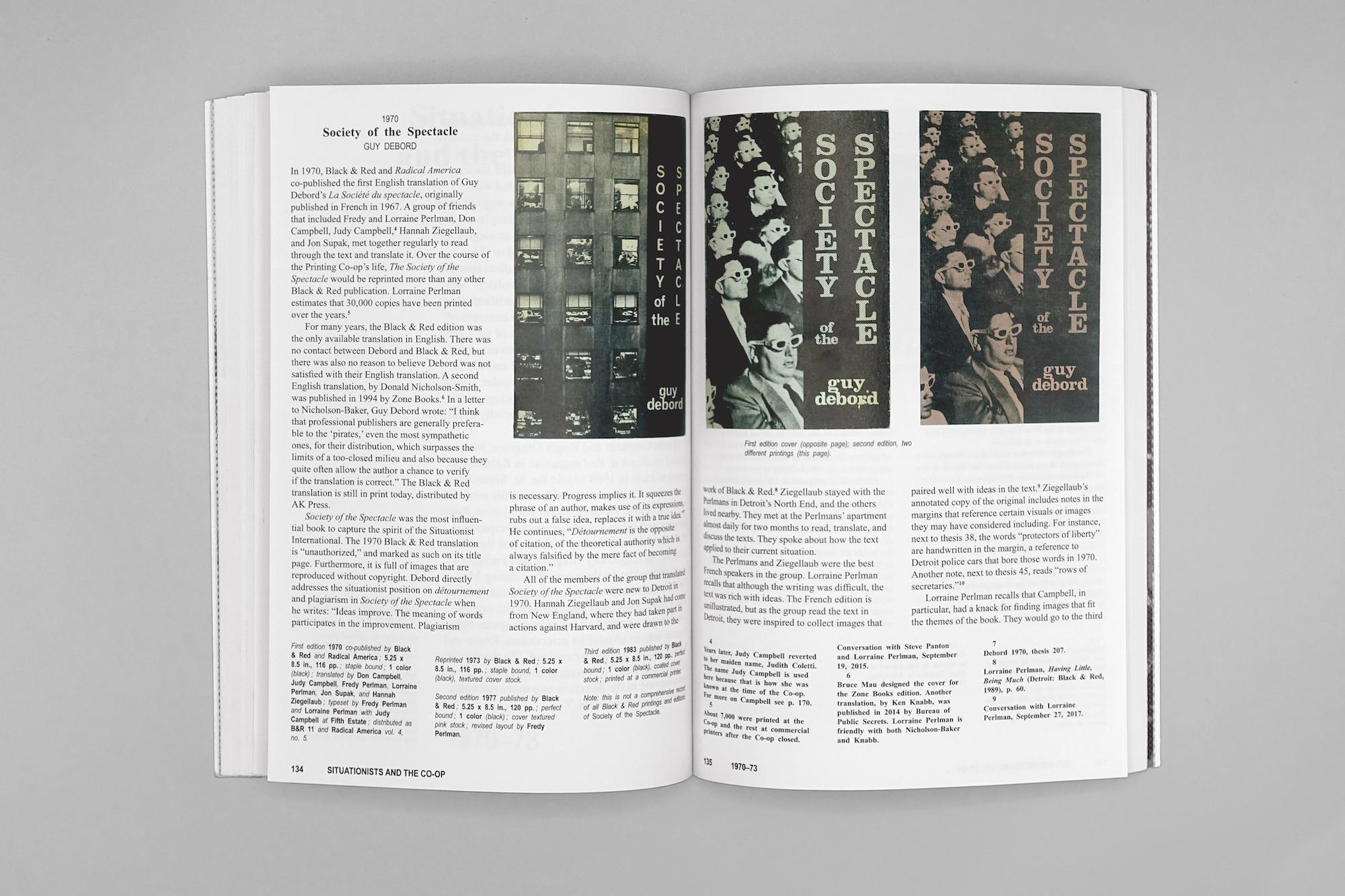

The Detroit Printing Co-op published magazines for Black & Red (which became and remains a radical publisher) and Radical America, founded by the Perlmans’ friend Paul Buhle. Along with works by Grace Lee Boggs and the Trinidadian Marxist CLR James, they also printed 30,000 copies of an “unauthorised” translation of Guy Debord’s 1967 Situationist text The Society of the Spectacle, their most popular and influential production.

“Perlman became his own ideal synthesis of intellectual, labourer and producer”

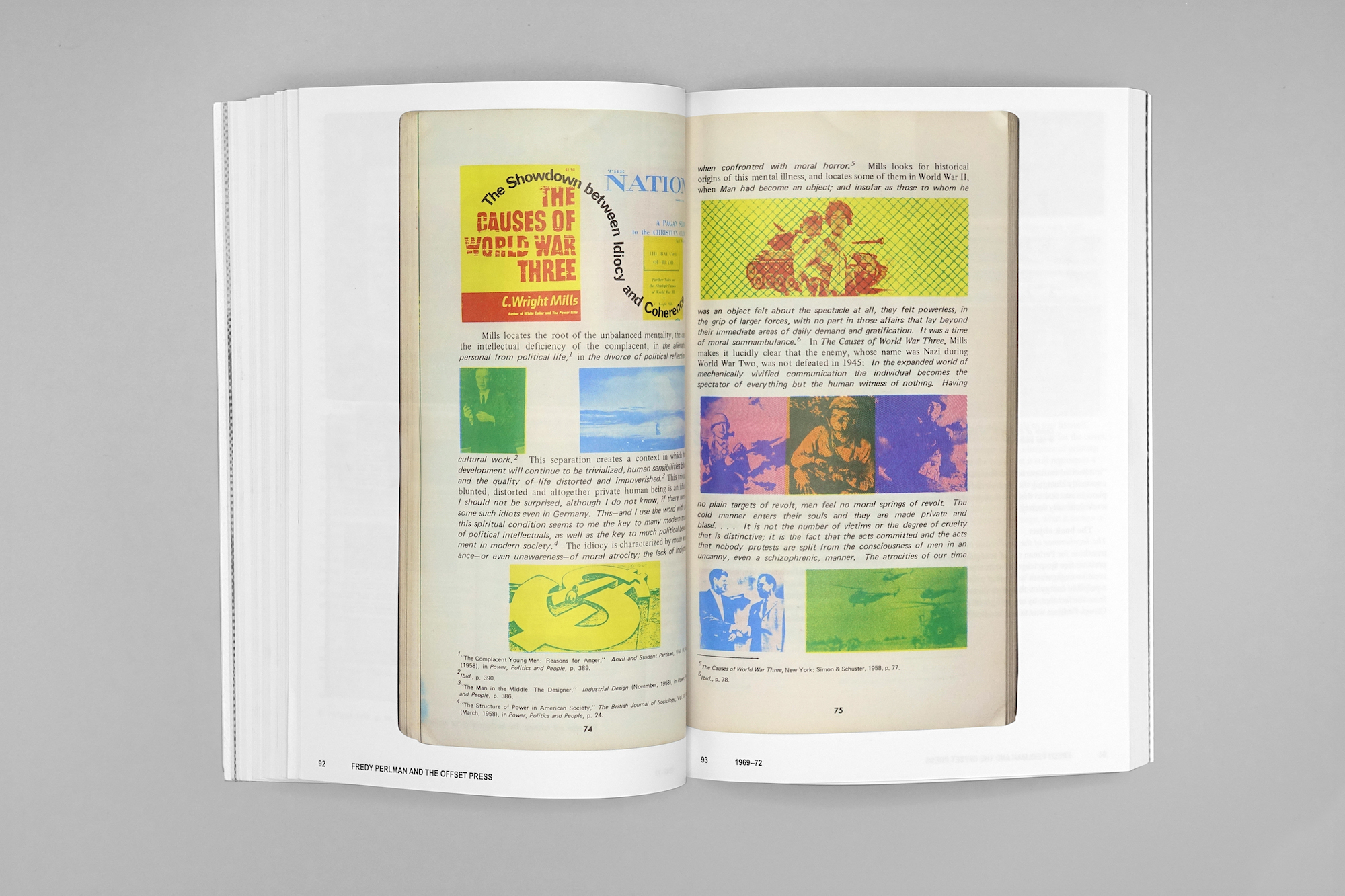

Perlman experimented with multiple-colour offset printing, inserting silkscreen images into the text of books as an extension of meaning. He became his own ideal synthesis of intellectual, labourer and producer, an idea inherited from the radical sociologist C Wright Mills. Being generous, you could see Perlman as a precursor to the sort of contemporary author whose texts are informed by their own selection of embedded images.

Associate Professor of Graphic Design at Wayne State University, Aubert attempts in the book to catalogue all the texts printed by the Co-op or associated with its ethos. Images from as many as can be found (including radical high-school news sheets, calendars and notices to the neighbourhood) are lovingly reproduced. Sometimes they happen to be striking; sometimes they are facsimiles of whole pages typed in Courier. But much like Fredy’s collages of his own words, lengthy quotes by others and images, these facsimiles produce an effect of one text momentarily giving way to another.

There is a running theme of how hard it is to effect change. The most enlightening passages are accounts of people without the mix of principle, drive and capability that allowed the Perlmans to produce project after project.

Badly-managed student bodies attempt to organise protests. No one turns up. The Perlmans print a leaflet inviting locals to “collaborate… in the production of a publication about what it was like to live and work in Detroit”. Only one person replies. Early in the description of a newsletter aimed at radicalising “non-managerial secretaries, architects, craftsmen, and engineers… in the Detroit area”, we are told: “These organising efforts did not ultimately succeed”.

“Had he lived beyond 1985, the early utopian, unregulated internet would surely have been his element”

But what emerges most powerfully is the tirelessness of the Perlmans. There doesn’t seem to have been a moment where they weren’t writing or translating a new text. These anarchist works aren’t widely available or widely cited in the mainstream, but we see moments where they could plausibly join it now. In The Continuing Appeal of Nationalism (1984), Fredy Perlman argued that “After the national socialist war, nationalism ceased to be confined to conservatives… Leftist or revolutionary nationalists insist that… theirs is a nationalism of the oppressed, that it offers personal as well as cultural liberation”.

In Against His-Story, Against Leviathan!—perhaps Perlman’s best known work—he stated his belief that “civilisation” began when people started displacing and enslaving each other, and that forms of progress are ultimately destructive to ecology. Had he lived into our age, perhaps he’d have been hailed a mainstream visionary.

Danielle Aubert, The Detroit Printing Co-op: The Politics of the Joy of Printing

Published by Inventory Press

VISIT WEBSITE