October Gallery is a rare thing. It’s located in a quiet spot in Bloomsbury, tucked behind Russell Square. It’s been going for forty years and has done many significant things in those four decades, yet somehow it’s a place that many miss. As the gallery’s director Chili Hawes and artistic director Elisabeth Lalouschek write in a new book that celebrates its fortieth birthday year, people often ask: “What exactly is this place?”

Dream No Small Dream, Celebrating 40 Years of October Gallery documents the colourful four-decade-long history of this somewhat eccentric institution. A self-portrait unfolds through its founders, long-serving staff members, exhibiting artists, friends and “fellow travellers”, as well as plenty of images documenting the radical events, exhibitions and performances that have taken place at the gallery over the years.

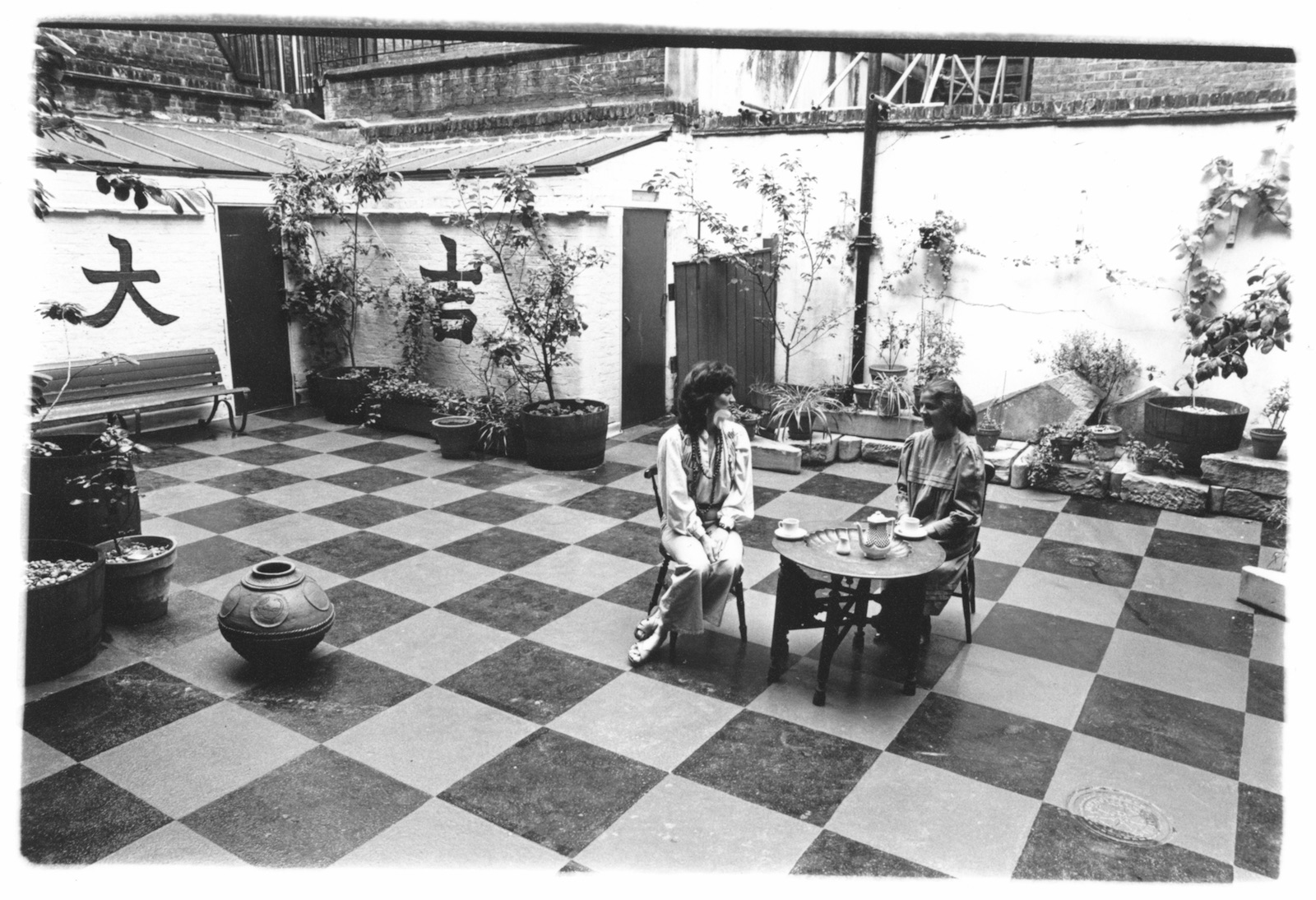

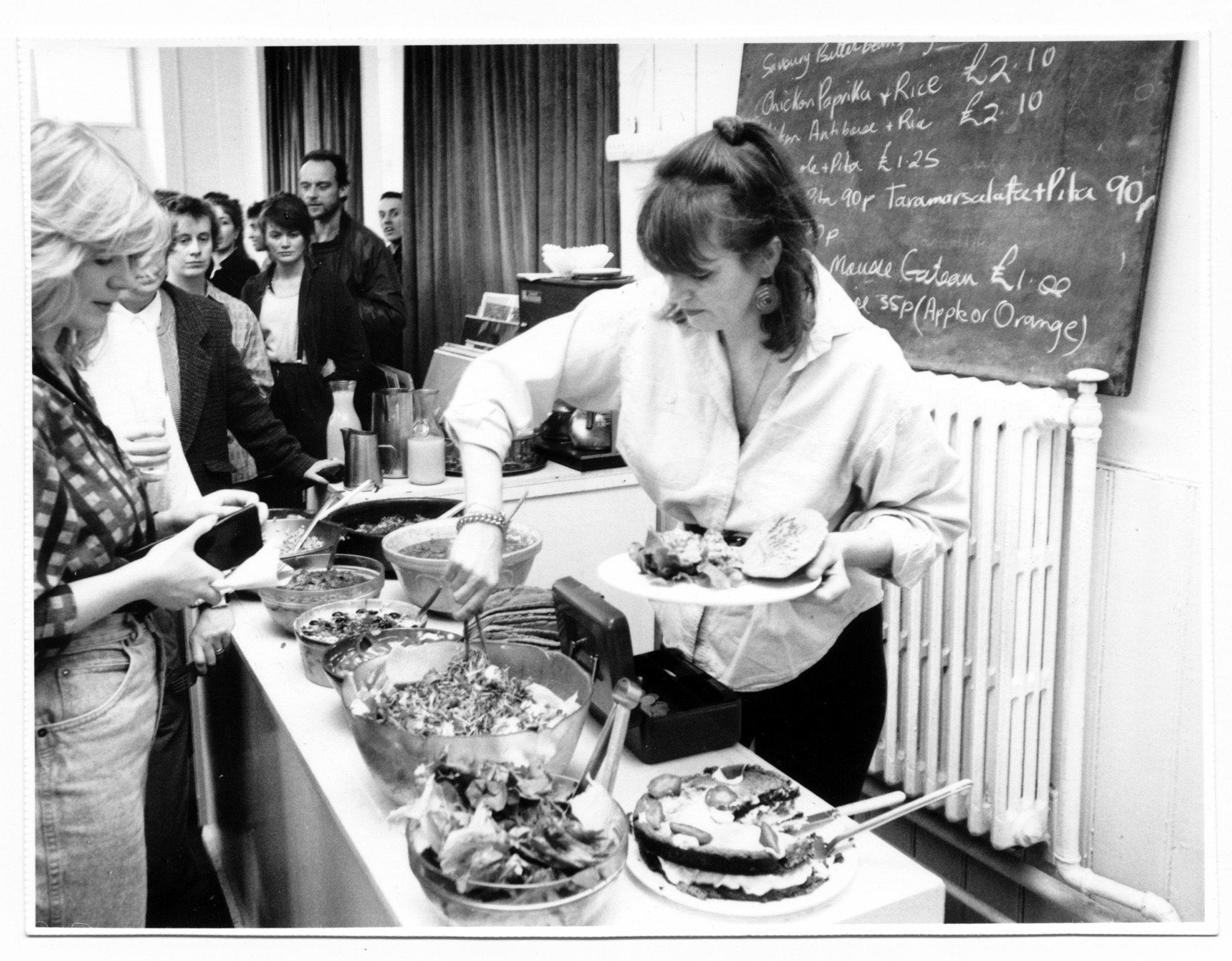

October has remained maverick because it isn’t run like most slick, commercial London galleries. Housed at Ludonia House, the space feels more like a community centre sprawling over three floors, a homey meeting place with its cafe and slightly disheveled look—the kind of place you might discover something, rather than see what’s already been plucked and polished for the art market. Then there are the staff—many of whom have been with the gallery since the very beginning, and remain loyal—and who act like a madcap sort of family rather than bloodthirsty business people.

“I broke down in tears, thinking, ‘What have I gotten myself into now?’”

The way October Gallery has been run since it opened in 1979 has also been something of an anomaly in the context of the UK’s commercial art capital. It has championed the Transvangarde movement, and has a radical way of thinking about which artists to show, and how. It’s surprising that in somewhere as obviously multicultural as London there are so few art venues that truly go beyond the Westernized ideals of aesthetics and display.

Rather than showing avant-garde art that had been canonized by European capitals, the people behind October Gallery have been involved in the living, breathing avant-garde as it exists in countries throughout Africa, Asia, the Middle East and Australia. More often than not, this has come from firsthand contact on the ground. Before the gallery opened, co-founder John Allen hung out with Brion Gysin and William Burroughs in Tangiers; Hawes was herding cattle and warding off deadly snakes in the Australian outback; and Elisabeth Laloushek had personal meetings with the reclusive Kenji Yoshida, who would become one of their many revelations.

The story of October Gallery that emerges from the publication isn’t one of glitz and glamour, but one of epic adventures, constant travel and chaos. Allen, together with the theatre director Kathelin Grey and the artist and actress Marie Harding, bought Ludonia House in 1978 for the purposes of building a utopian gallery, where they could show the kind of artists they had met but didn’t see represented in the West. When co-founder and director Hawes arrived that same year—from Colorado via the South of France—she recalls, “the wooden floors were black with tar; the splotchy painted walls were toilet green. Worst of all was the pervasive smell of dry rot, which covered one quarter of the building. I broke down in tears, thinking, ‘What have I gotten myself into now?’”

The Mexican architect Margaret Augustine was brought in to lead the renovations of the space, which were hands-on, according to Hawes’s account (she herself is a skilled plasterer). Their first exhibition opened in February 1979: a show of paintings by a neglected British painter Gerald Wilde. It wasn’t the precedent-setting inaugural exhibition, however. The team’s intentions were already set on showcasing art from places further from London. At the beginning of the 1980s, that wasn’t as common as it is now: none of the major museums, as Hawes points out, were interested in collecting or showing contemporary African art—Tate Modern only presented its first African artist in a solo exhibition in 2013, with a survey on the Sudanese Modernist, Ibrahim El-Salahi. “That’s thirty years after our first showing of the wonderful Moroccan artist, Hamri, to whom we were introduced by Brion Gysin and William Burroughs,” she notes.

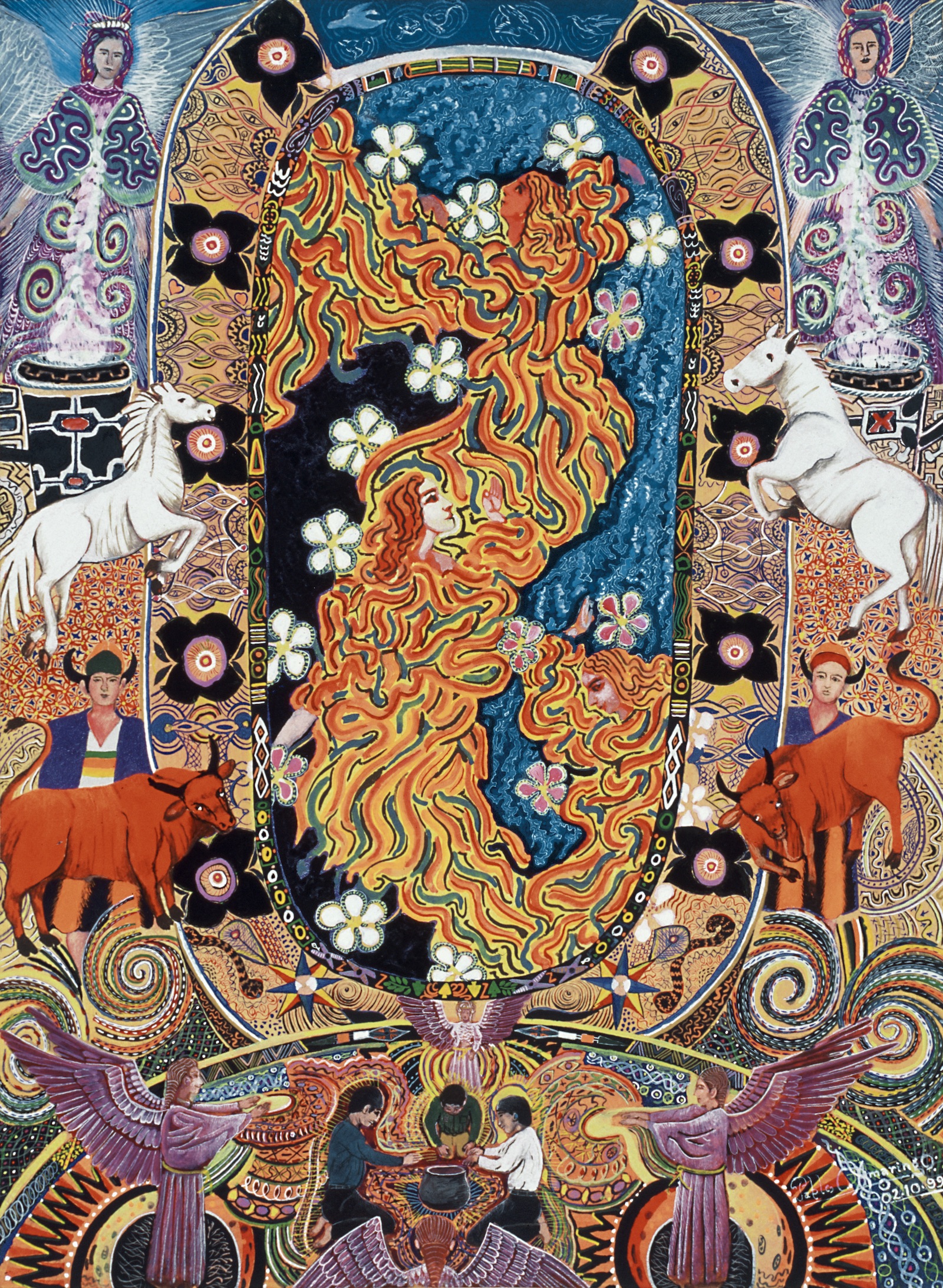

As Dream No Small Dream details through various voices and stories, there has been a cast of characters—poets, actors, artists and directors—who have passed through the gallery over the decades, each activating it in their own way and introducing new communities to the space; some stayed, some moved on and some passed away since. In the 1980s, for example, the influence of the late Tamil writer and publisher MJ Tambimuttu, also known as Tambi, was evident. Then the editor of Poetry London, Tambi had an office at the gallery, and introduced many Indian and Sri Lankan artists and poets to October. There were artists like Manuel Mendive, who was invited from Cuba to exhibit by Laloushek (a painter who had exhibited at the gallery and became part of its management team in 1987) and turned up with his entire dance troupe. “There was no limit to what was possible,” Laloushek reflects. She has been a driving force at the gallery, introducing young artists such as the painters Laila Shawa and Xu Zhongmin.

“October has remained maverick because it isn’t run like most slick, commercial London galleries”

There were plenty of hard times for the gallery, as Gerard A Houghton—who leads special projects—writes, it stayed afloat at times only thanks to its “low-expenditure, collective approach: there were no lavish outlays, team members received no regular wages”. Luckily, money was never the main motivation for October—another radical reinvention of the gallery model that is made clear over the pages of this book. “We didn’t have any money, and didn’t expect to make a lot of money. We just carried on determinedly, whatever happened,” Hawes remarks.

Recently October Gallery has received attention due to the rise and rise of contemporary African art—it was the first UK gallery to present and publish a book on El Anatsui, and to establish profound, enduring connections on the continent (Naomi Wanjiku Gakunga, Nnenna Okore and Eddy Kamuanga Ilunga are part of their current cross-generational roster). But this is only one part of the October Gallery story; it’s continued to reach places no other galleries go and to show artists who no-one else is talking about. The team has put on shows of Tibetan Buddhist art and Arabic calligraphy; there have been dance performances and buffet dinners, nudity and newness. October Gallery might not be trendy—it’s hard to say if it’s been ahead of its time, or just on another timeframe altogether—but as this document affirms, it’s certainly unique.

There’s a quote by Simon Njami, editor of the now-defunct Revue Noire, included in the book that perhaps says it best: “the Transvangarde is a concept that defines the art of the future, an art created by syncretism and exchange. In this context, it is clear that the future of art is currently being created beyond the boundaries of the Eurocentric vision. The cultural inheritance of non-Western artists carries within it the multiplicity of experiences required to construct a broader and more expansive definition of art, an art which touches a larger and more comprehensive community.”

Dream No Small Dream: Celebrating 40 Years of the October Gallery

BUY NOW