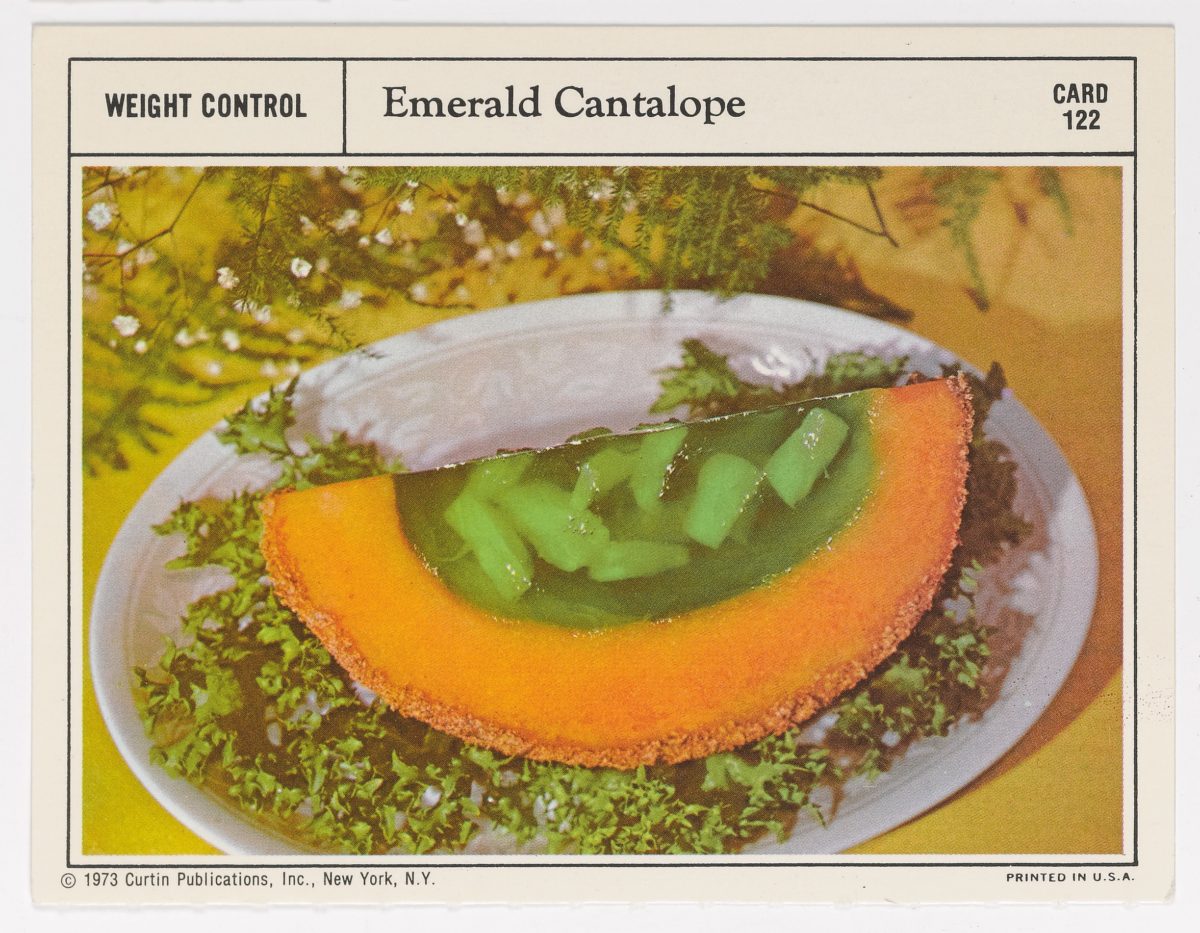

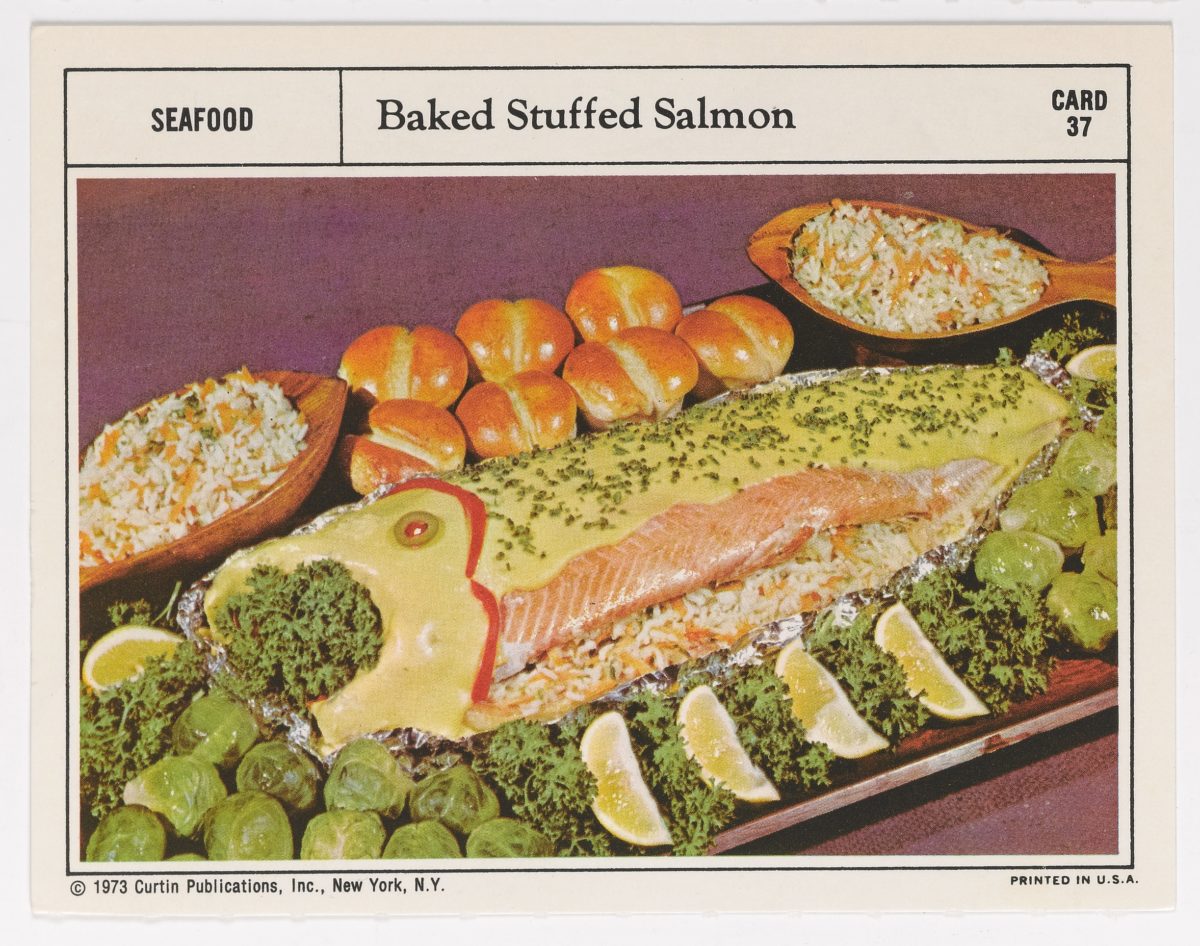

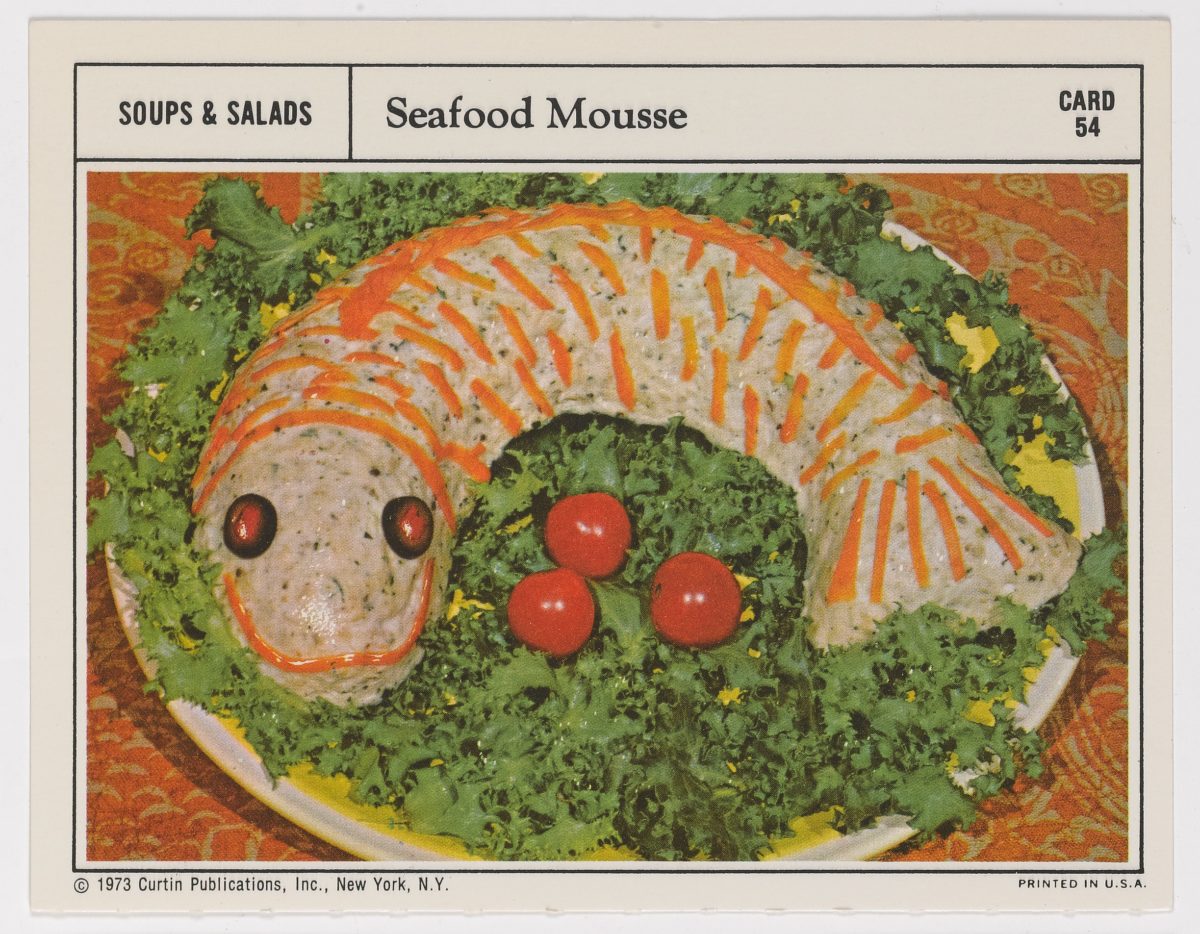

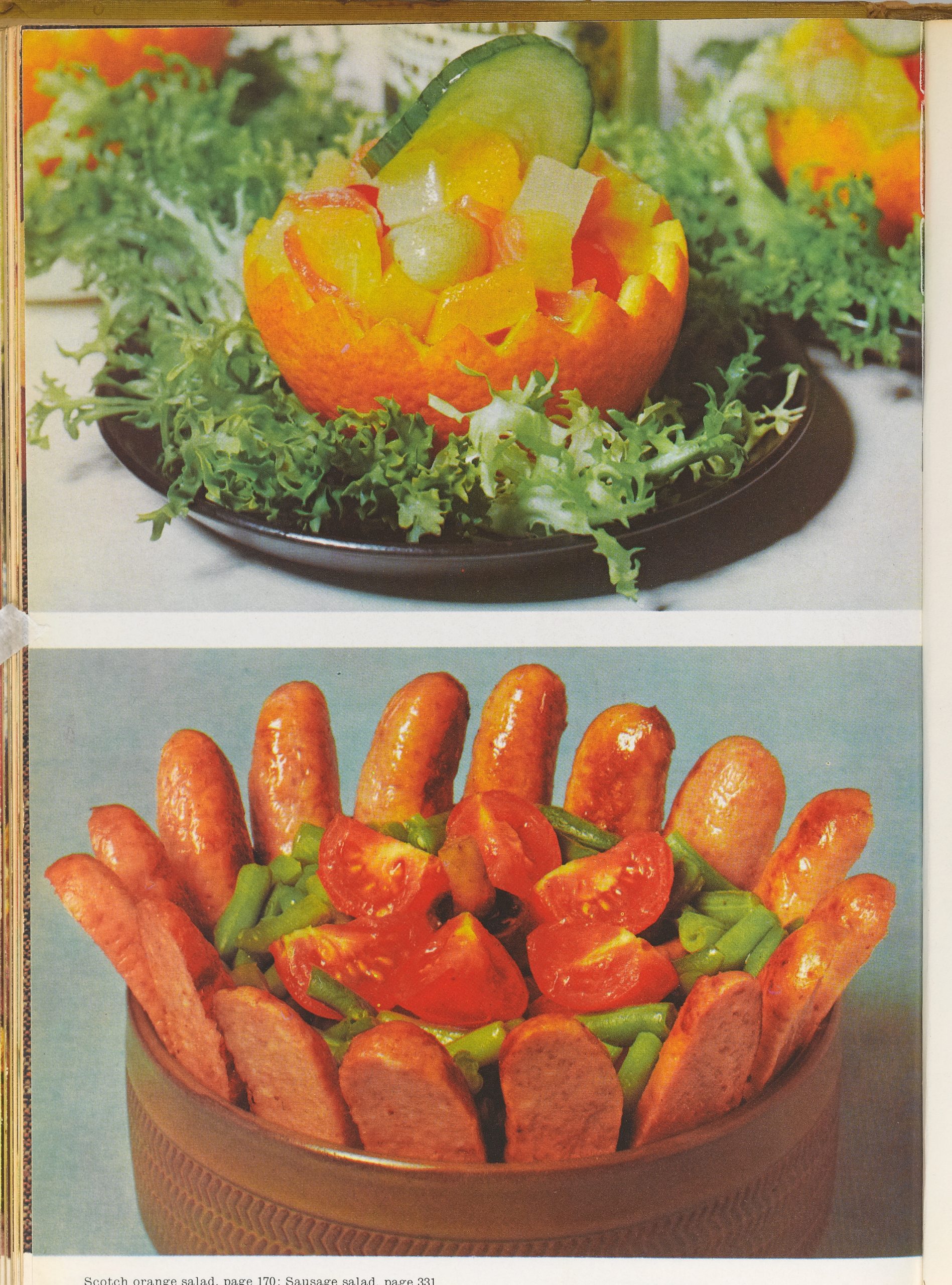

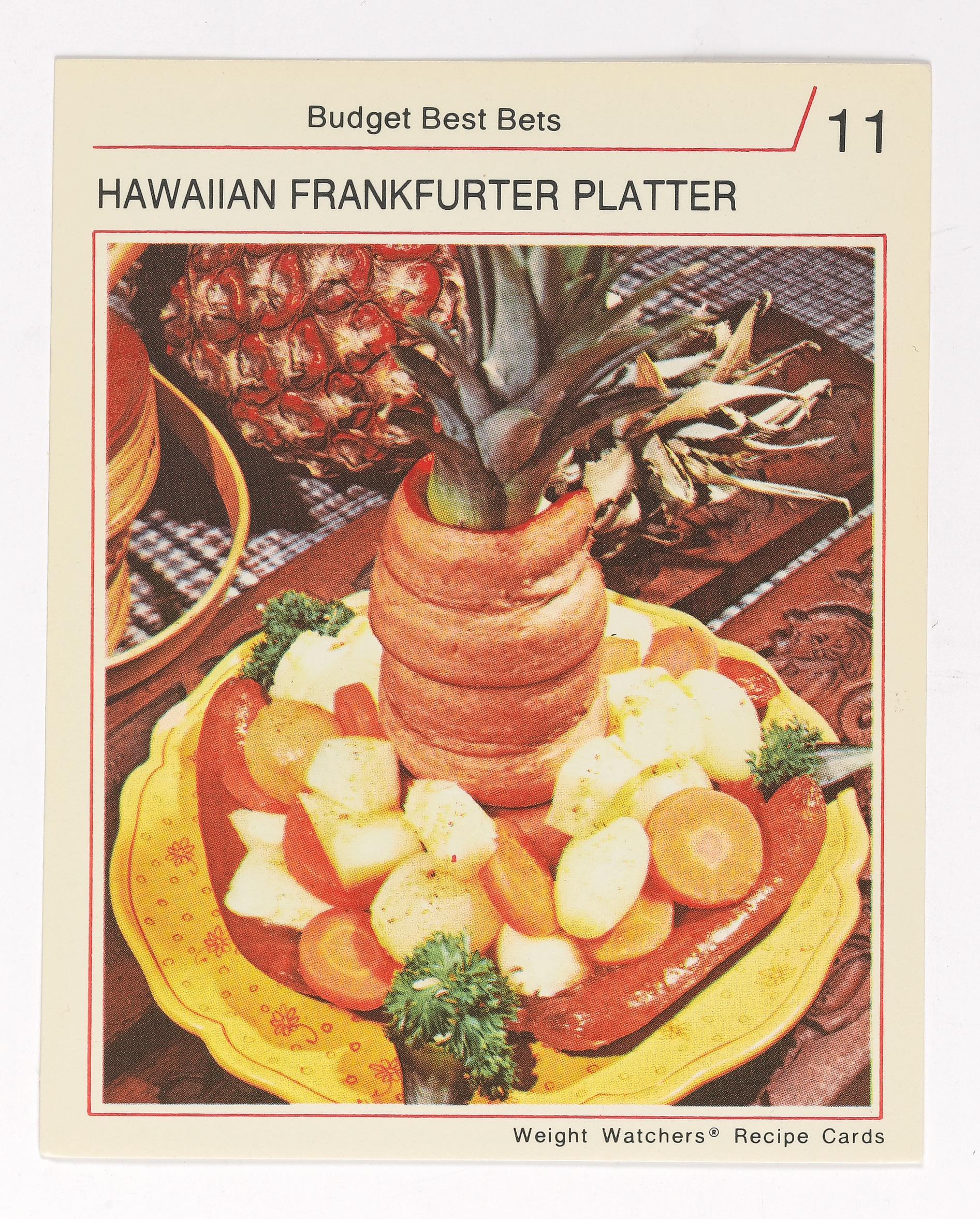

A seafood mousse grins at you from a bed of salad, moulded into the shape of a fish with olives for eyes and carrot strips for scales. A crown of frankfurters encircles an infernal casserole of potatoes, green beans and Campbell’s cream of mushroom soup. Strips of cheese and sausage are suspended in glistening aspic, topped with a vermilion peak of Padrón peppers. An erect banana protrudes from a slice of tinned pineapple, a cherry placed on its tip. Lemon piglets, apple turkeys and cupcake clowns beckon you in. Welcome to the absurd world of 1970s dinner party food.

Of all the aesthetic echoes of the 70s—whether the millennial penchant for moustaches or the return to maximalist decor—today’s fascination with 70s food is the most bizarre. Largely responsible for this is literary agent Anna Pallai. Over the past five years, Pallai has collected images of retro meals from cookbooks such as Supercook and Good Housekeeping, and from the recipe cards of McCall’s, Weight Watchers and Betty Crocker, and shared them on social media under the moniker “70s Dinner Party”.

“It started in 2015 when I was at my mum’s house flicking through old recipes,” Pallai tells me. “I idly set up a

Twitter account to share the images, to amuse myself as much as anything.” But kitsch 70s meals proved surprisingly memeable, and Pallai’s socials rapidly gained traction (her Twitter account now has more than 154,000 followers; her Instagram more than 62,000). “It happened weirdly quickly,” she remembers. “The picture that probably triggered it was of a dish called Ham and Bananas Hollandaise, which contains whole bananas wrapped in ham with hollandaise sauce on top.” The popularity of Pallai’s approach to food porn led to the publication of her book, 70s Dinner Party: The Good, the Bad and the Downright Ugly of Retro Food in 2017.

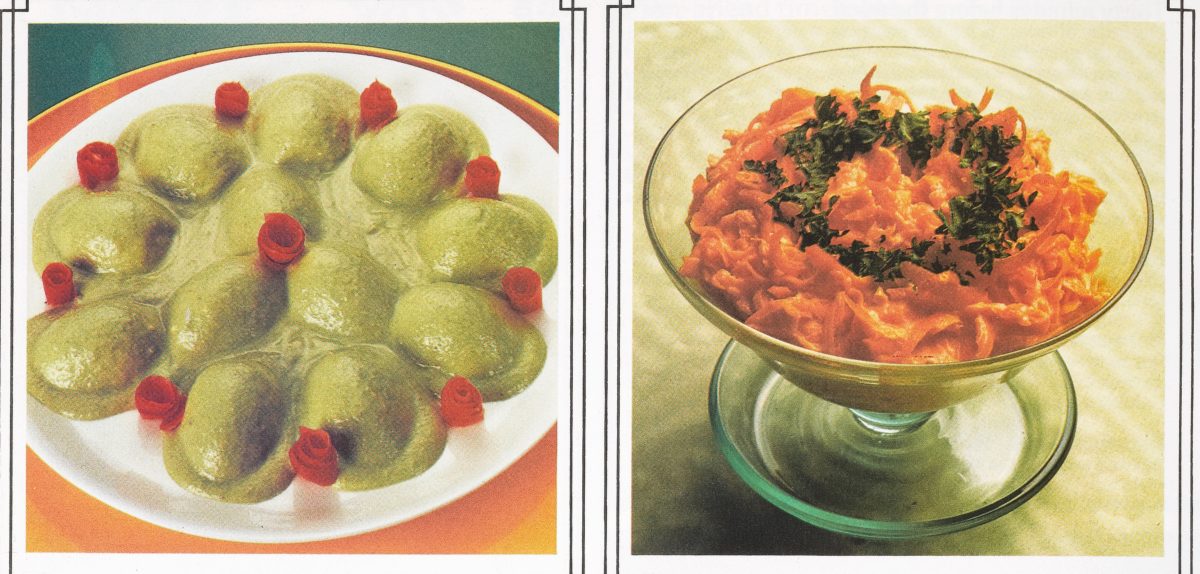

- Robert Carrier, Eggs Guacamole (left); Untitled (centre left); Untitled (centre right); Little Vegetable Towers (right), Carrier’s Kitchen, 1980. As featured in Anna Pallai, 70s Dinner Party, 2017. Courtesy the author

“Of all the aesthetic echoes of 70s, the fascination with food is the most bizarre”

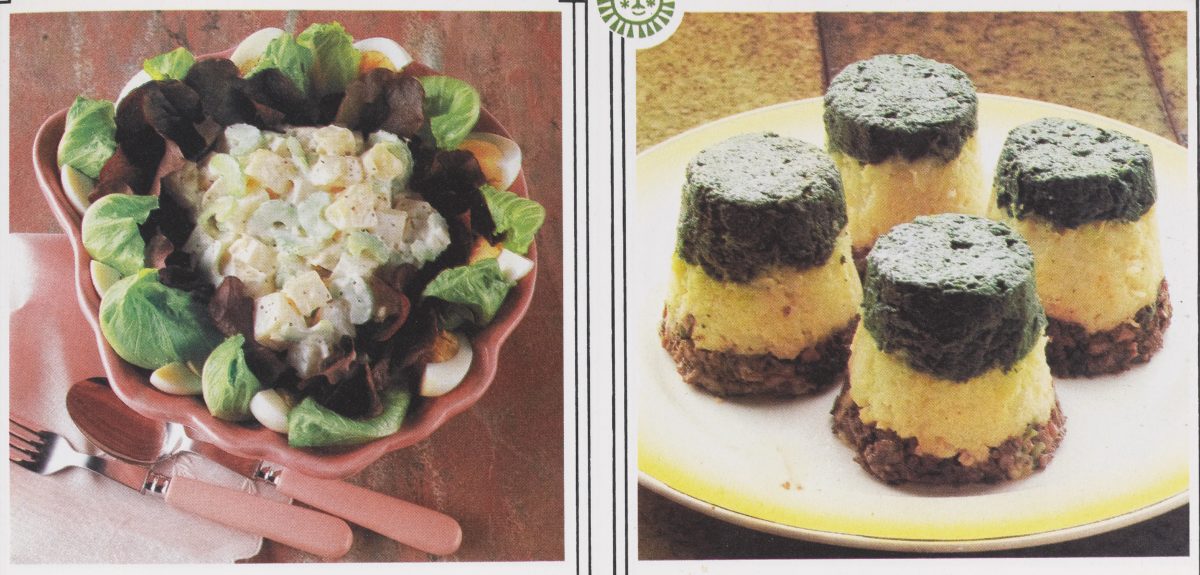

For a generation used to capturing sourdough bread and avocado brunches through an iPhone lens, the gelatinous platters of the atomic age inject much-needed fun into digital food sharing. “A lot of why I started this was as a reaction to the sort of ‘holier than thou’ food posting on Instagram, which I really didn’t like,” Pallai explains. Far from the clean eating fads of today, 70s Dinner Party submerges the viewer in a realm of artifice and unashamedly bad taste; it does so visually, through lurid colours and crude shapes, and literally, through processed ingredients and incongruous flavours, such as chicory, chopped apple and Heinz baked beans. Pallai’s project is a window into a bygone age of aspirational and elaborate food styling, in which tinned and frozen convenience foods were dressed up with eccentric garnishes: a way of making life ‘easier’ for hosting housewives while still expecting them to produce showboat spreads.

- Emerald Cantalope (left); Baked Stuffed Salmon (centre); Seafood Mousse (right), Recipe Cards Curtin Publications Inc., NYC, 1973. As featured in Anna Pallai, 70s Dinner Party, 2017. Courtesy the author

This habit of playing with food extended beyond the kitchen and into the art of the time. Sausage innuendoes are equally present in the work of surrealist photographer Guy Bourdin. In a provocative double-page spread for Vogue Paris in 1981, Bourdin captures two models feeding each other frankfurters in bed over a large plate of sauerkraut. Similarly, Pallai’s array of culinary characters evoke the fantastical food worlds of Swiss photographers Peter Fischli and David Weiss, who poked fun at the self-important conceptual art genre. In their 1979 Wurst Serie, the pair use processed meat to create ridiculous scenes, such as a carpet shop and a crowd of fancy sausage creatures admiring their reflection in a mirror.

“For a generation used to capturing sourdough through an iPhone, the platters of the atomic age inject much-needed fun into digital food sharing”

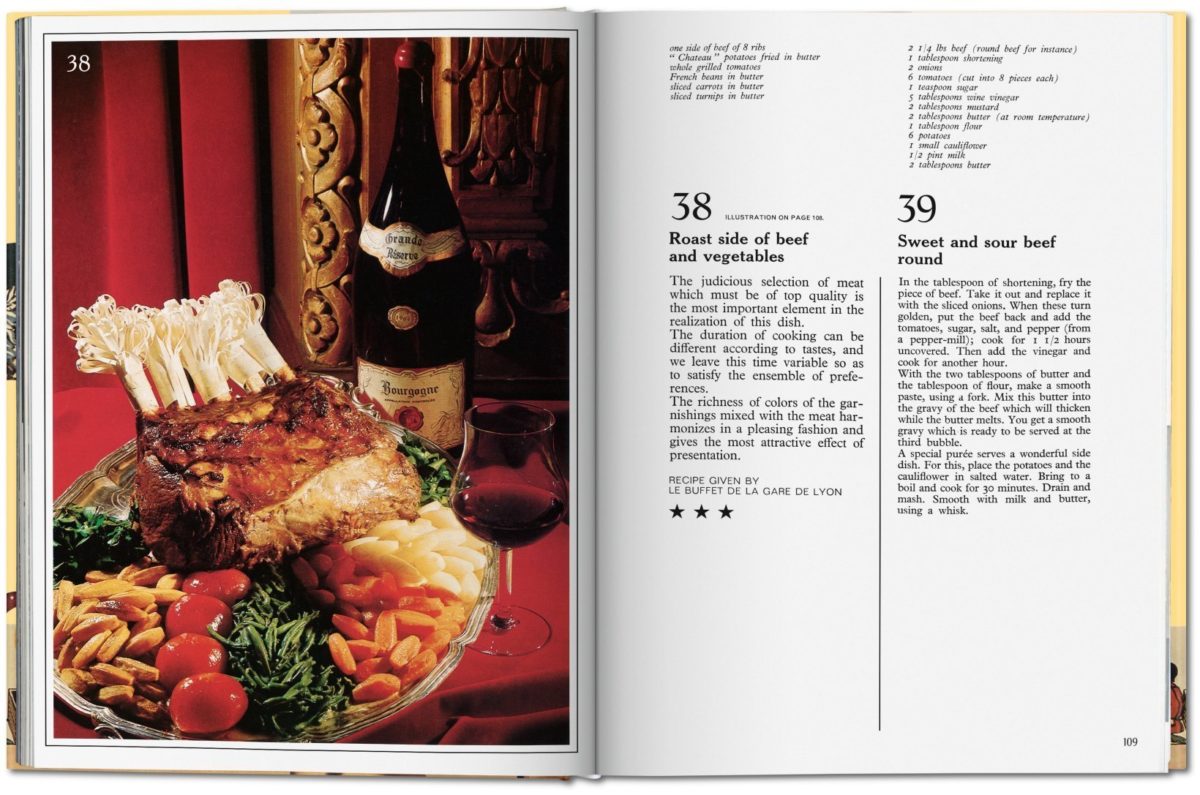

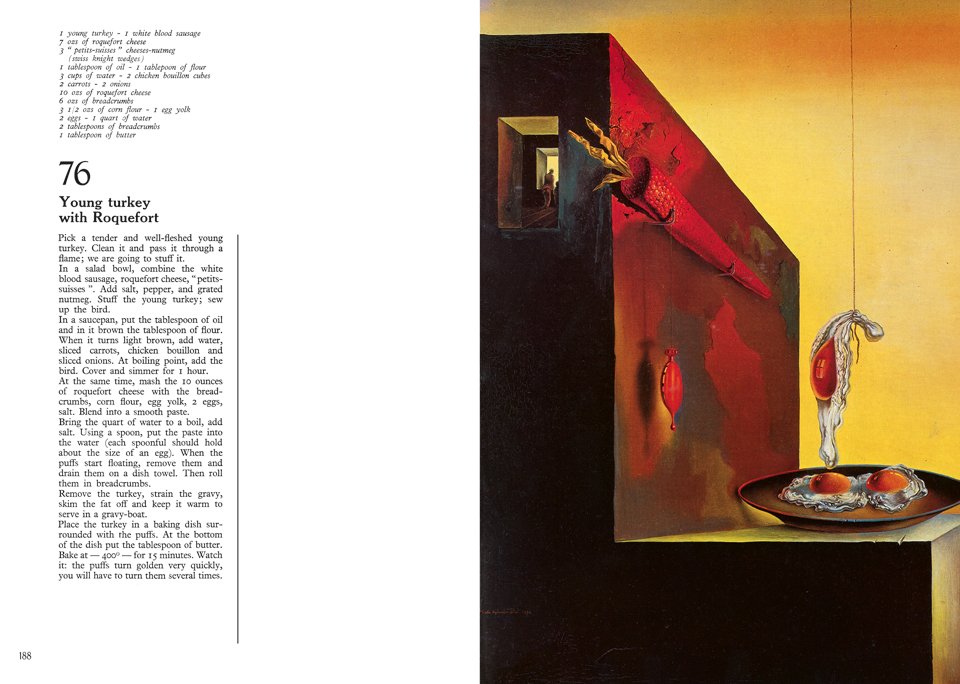

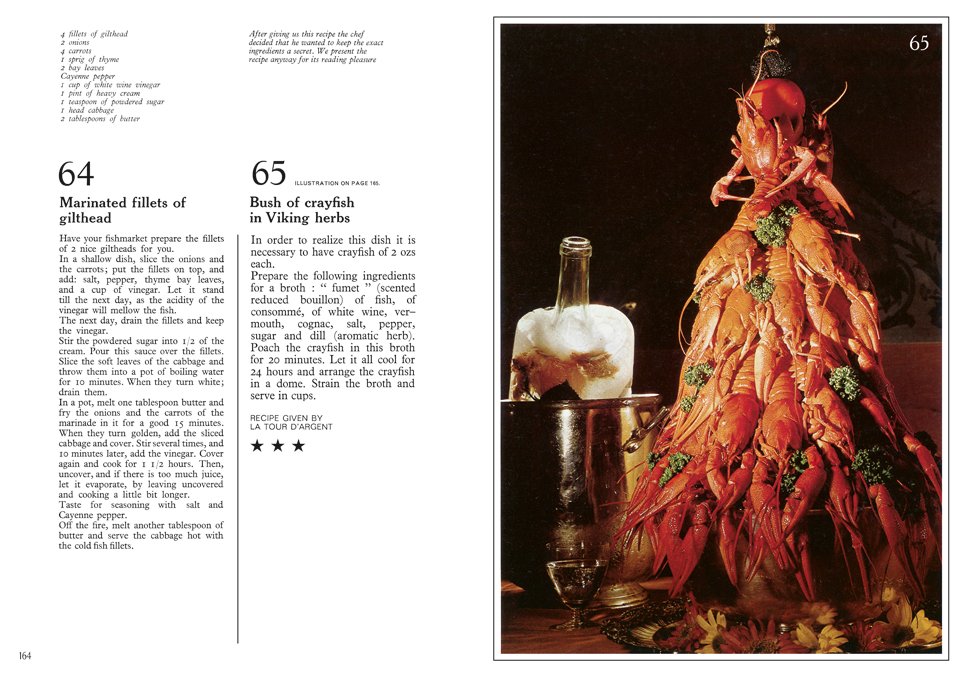

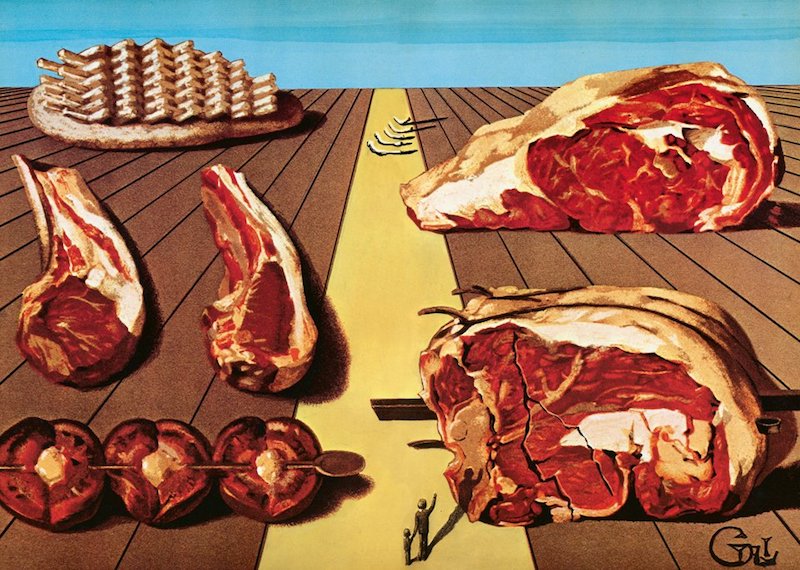

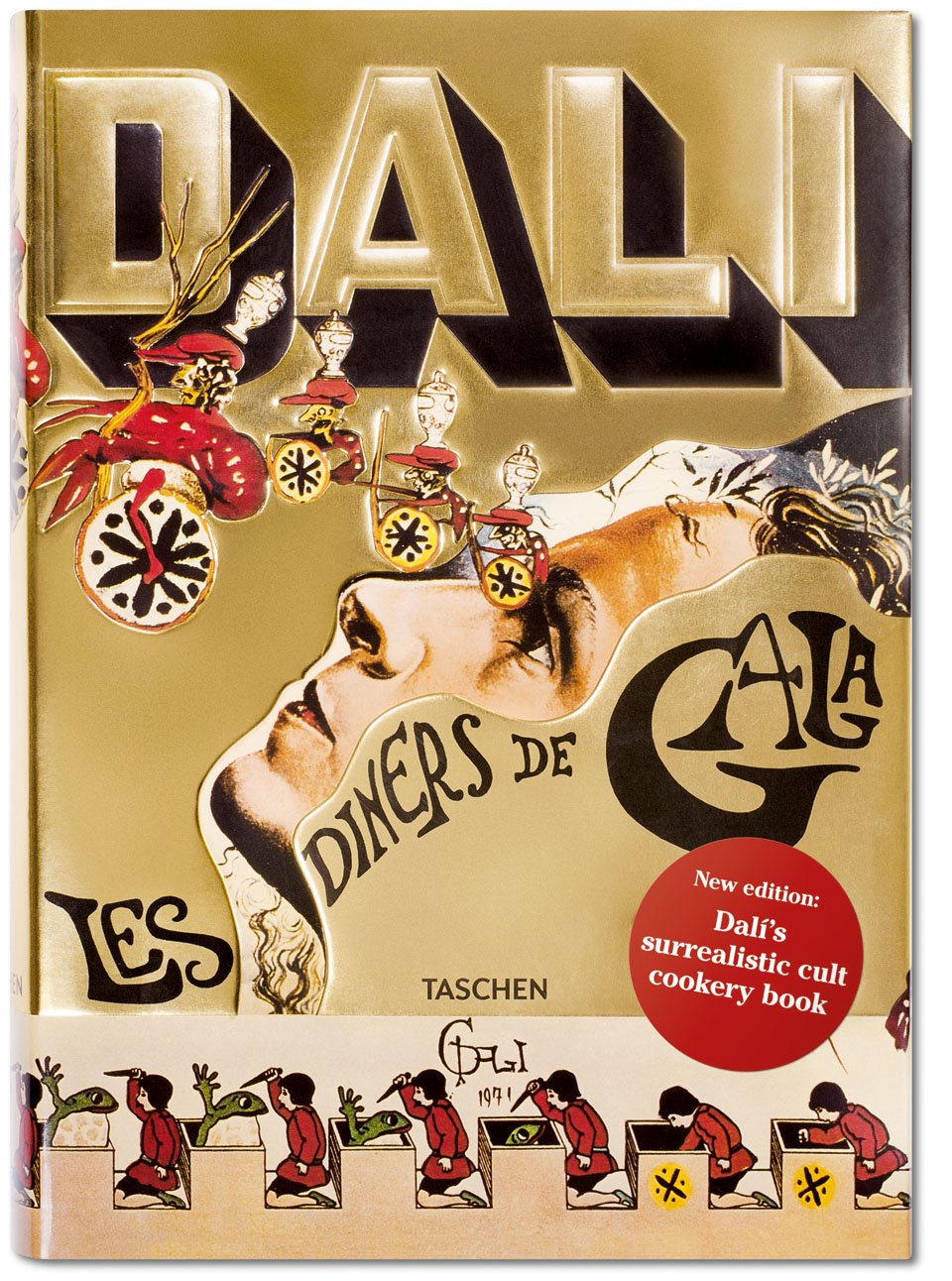

It was Salvador Dalí, however, who shared most proudly in the era’s tradition of food-as-spectacle. Just as the retro cuisine of the 70s refigures the dinner table as a trippy dreamscape, so too did Dalí in his garish book of recipes, Les Dîners de Gala (1973). A love letter to food, the book is a culmination of years of opulent dinner parties thrown by Dalí and his wife, Gala. Featuring sumptuous dishes of “Veal Cutlets Stuffed With Snails”, “Frog Cream” and “Toffee with pine cones”, Dalí’s 136 recipes were created with chefs at Paris’s gastronomic powerhouses, like La Tour d’Argent and Maxim’s. At once a cookbook and a manifesto for sensory hedonism, it is, like Pallai’s project, an affront to restraint and meek health consciousness. “If you are a disciple of one of those calorie-counters who turn the joys of eating into a form of punishment, close this book at once;” Dalí warns in the introduction. “It is too lively, too aggressive, and far too impertinent for you”.

By the 1970s, Dalí had long since broken with the surrealist movement and was commercialising himself to fund his extravagant lifestyle: he was the face of the Lanvin Chocolate commercial in 1968 and designed the Chupa Chups logo in 1969. “I see Les Dîners de Gala as a commercial venture, too,” says art historian Abigail Susik. “At this stage in Dalí’s career, he just wants cash.” Published during the protracted Vietnam War, Dalí’s glorification of “Monarchical Meats” and his lavish homage to the French cooking establishment appear in sharp contrast to the hippie counterculture of the time. “The feast in Les Dîners de Gala is an orgy of money,” Susik suggests. “It exposes the disgusting excesses of wealth, but it also valorises it.”

“Even within a cookbook devoted to fine dining, Dalí is drawn to the innate baseness of food”

Excess also extends into eroticism in the book. Dalí’s collection of “aphrodisiacs” are unsubtly titled “Je mange Gala”, while his recipes are interspersed with artworks dominated by the corporeal. Meat and human flesh become indistinguishable, while orifices, phalluses and primal pleasures abound. In one painting, a saint-like figure sits atop a tower of crayfish and dead bodies, blood oozing from her decapitated limbs. Dalí’s depictions of cannibalism and eroticism push the surrealist investment in the interrelationship between food, sex and death to extremes—a far cry from the sleights of hand and phallic vegetables that makes 70s Dinner Party so popular in the digital age.

And yet there are parallels to be drawn in how viewers react to such imagery. Followers of 70s Dinner Party can be split into two camps: it has a Proustian effect on those who experienced the cuisine first-hand while igniting a kind of morbid fascination among younger viewers. “I’d say it’s a very clear mix between people who are nostalgic for it and people who’ve never seen it before and can’t quite believe this stuff existed,” Pallai reflects. Dalí’s motivations are perhaps more consciously grotesque: deliberately associating food with viscerality from the outset, rather than seemingly innocent creations eliciting strong reactions years later. “Food is Freudian for Dalí,” says Susik. “I think he has very disturbed feelings about the way in which the mouth is an erotic orifice, a scatological orifice and also one that’s related to death. They’re always tied for him.” Even within a cookbook devoted to fine dining, Dalí is drawn to the innate baseness of food, a substance that so effortlessly turns high into low and is never as ‘clean’ as we might hope.

Though worlds apart, Dali’s cookbook and the stylised recipes of the 70s share a fixation with transforming food, the most basic human need, into something significant: whether that’s Dalí turning biscuits into the hair on a woman’s head or dinner party hosts carving swans out of apples as a parlour trick. And, in a post-Covid world in which communal food sharing is taboo, Pallai’s project becomes a digital form of feasting. Both 70s Dinner Party and Les Dîners de Gala serve us a vicarious banquet for the senses, bringing gastronomic gaudiness to more muted times.