With our freedoms and social contact limited by the Covid-19 crisis, self-isolation has been a constraining, frustrating and distressing experience for many. “I’ve heard lots of people compare their experience to being in prison, and some have asked for my advice on how to cope”, says Lee Cutter, an artist whose practice emerged whilst serving time in young offenders institutions between 2006-09. Cutter spent five months of that time waiting to be sentenced. He was held alone in a cell for twenty-four hours a day, allowed out once or twice a week to take a shower or make a phone call.

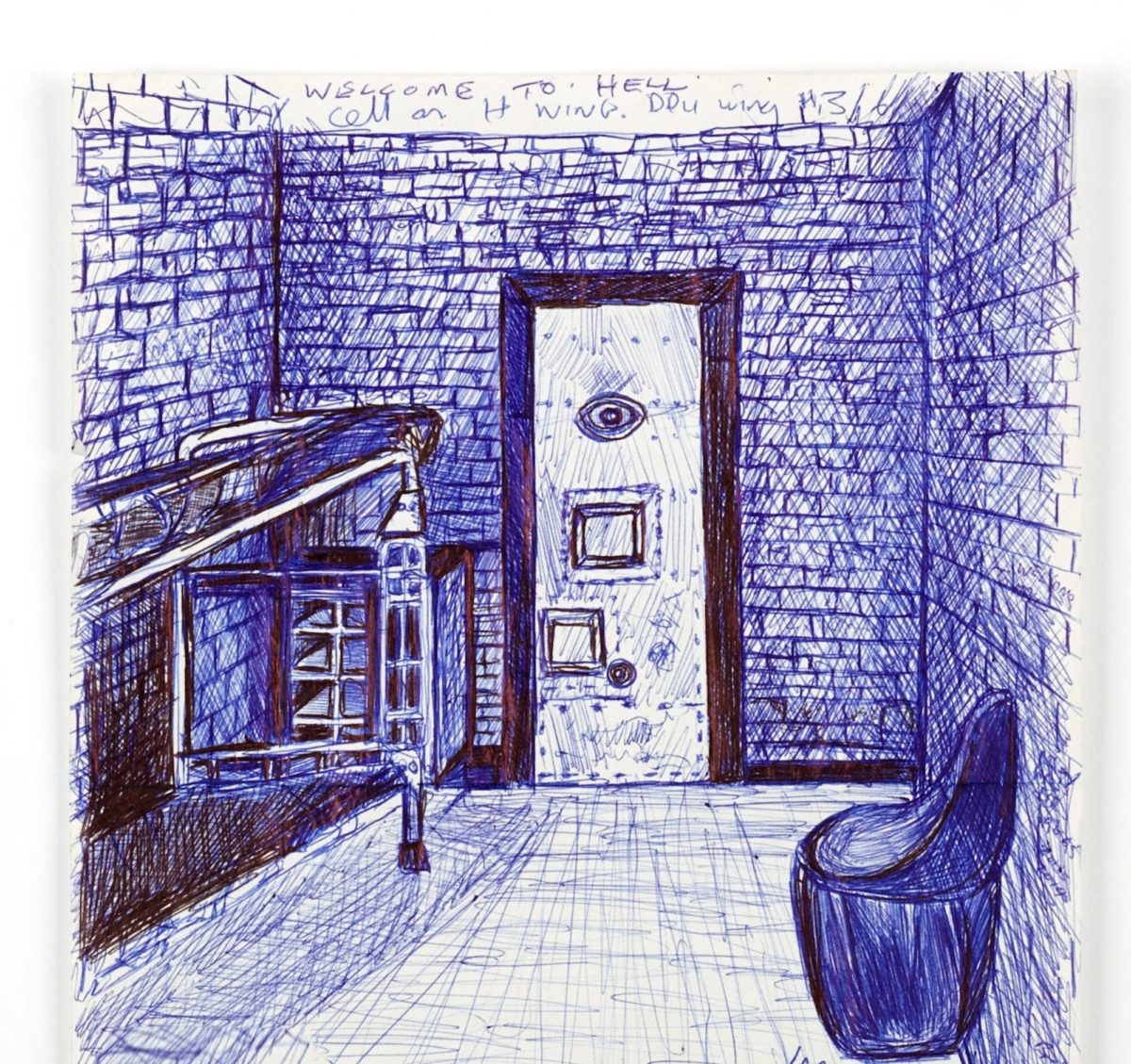

He started writing on the backs of letters using a pencil that had been accidentally dropped by a prison officer. “I was being consumed by those four walls and I needed to get my feelings out somewhere. Afterwards, I would rip them up and throw them away”. He then began to draw. He recalls that his imagination wasn’t functioning properly, that he could not draw anything beyond what he could see. “When I ran out of paper I started carving soap, just drawing the sink or doorframe”. Once, a prison officer found his carvings and destroyed them: “I don’t know why he did it. Some of them are like that”.

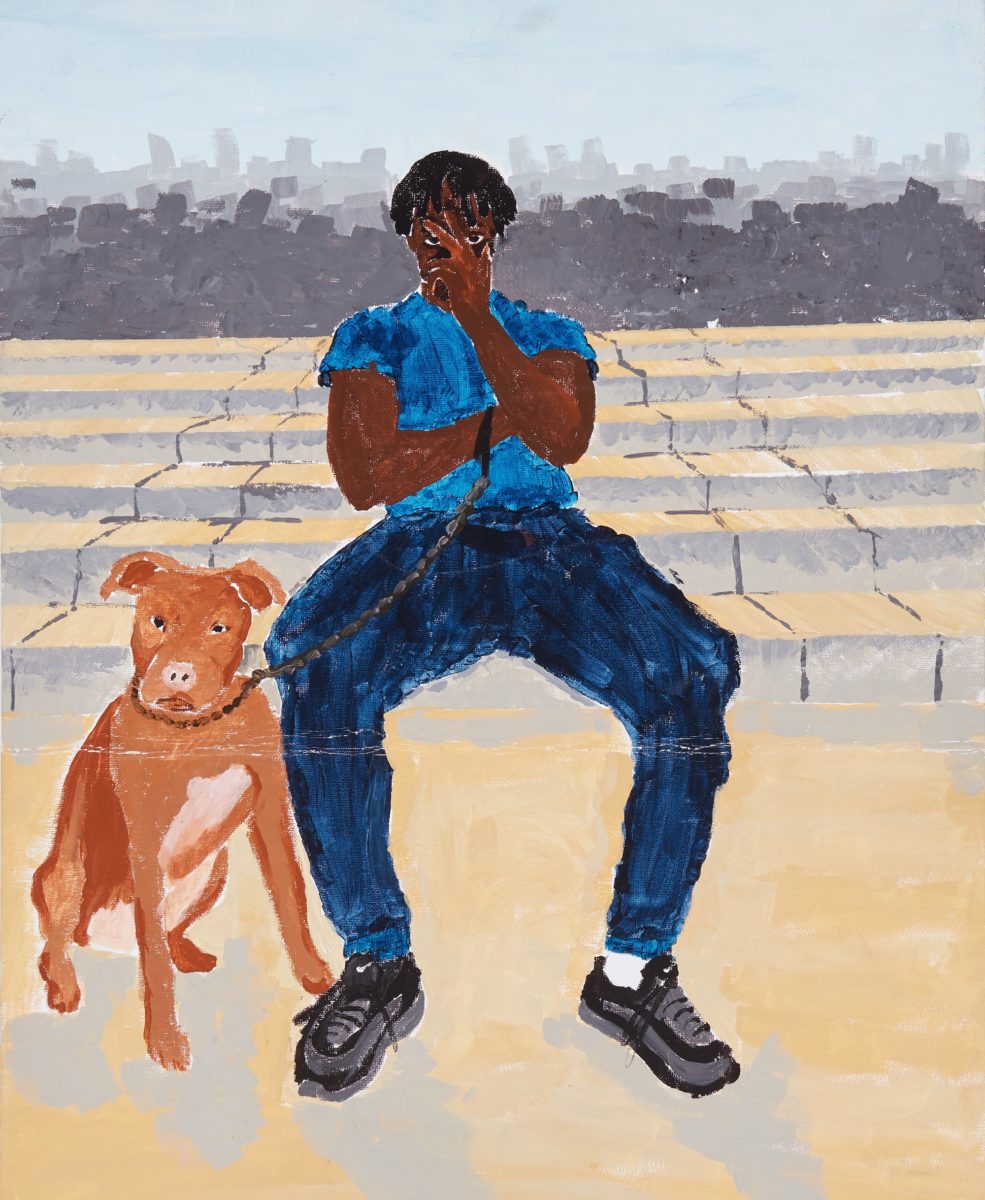

When Cutter was transferred to a different institution, he had access to more art materials, and began to make work regularly. Soon, other inmates and prison officers were swapping noodle packets and shower gel for paintings of their family members and pets, and he became known as “the artist”, a moniker that he says gave him a feeling of satisfaction and purpose. For me, somebody who was never told that anything I did was any good, or that anything I had to say mattered, this was huge”.

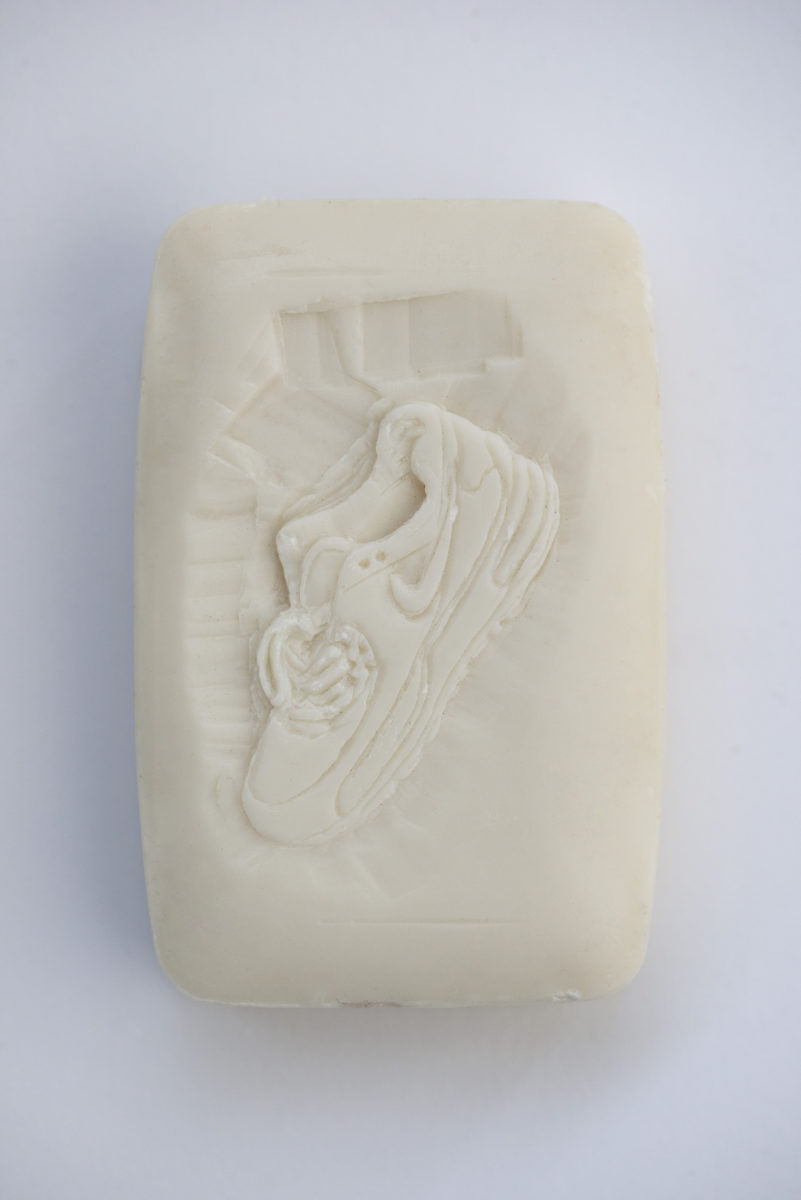

Cutter went on to study Fine Art at the University of Sunderland and the Royal Drawing School. During a research trip to the British Museum, he came across some stone artefacts. Shortly afterwards, he began to reincorporate soap carving into his practice, shaping images and text that detailed the rituals of everyday life in prison. He uses the same soap that tends to be available in UK prisons, called Buttermilk.

“For inmates, who describe never having received positive reinforcement, their decision to make art constitutes a radical act of self-belief”

“It’s cheap and you buy it in bulk. It smells overly strong and it really dries out your skin, so it’s not great as soap, but it’s good for carving”. A bar of soap is a widely recognisable and accessible material, but within Cutter’s work it signifies the ways that prison limits and homogenises the ways in which you can care for yourself. Our sense of smell is a powerful memory stimulant, and working with the soap forces Lee to spend time reflecting on the darkest period of his life.

Cutter entered his work to Koestler Arts, an organisation that holds annual competitions for art made in prisons and secure hospitals. They welcome submissions of everything from computer-generated music to nail art, which are assessed on equal terms with those of painting and sculpture. Exhibitions of submitted work are hosted annually by the Royal Festival Hall in London, in shows that have been curated by high-profile artists like Anthony Gormley and Sarah Lucas, and also by family members of inmates and people who have been victims of serious crimes.

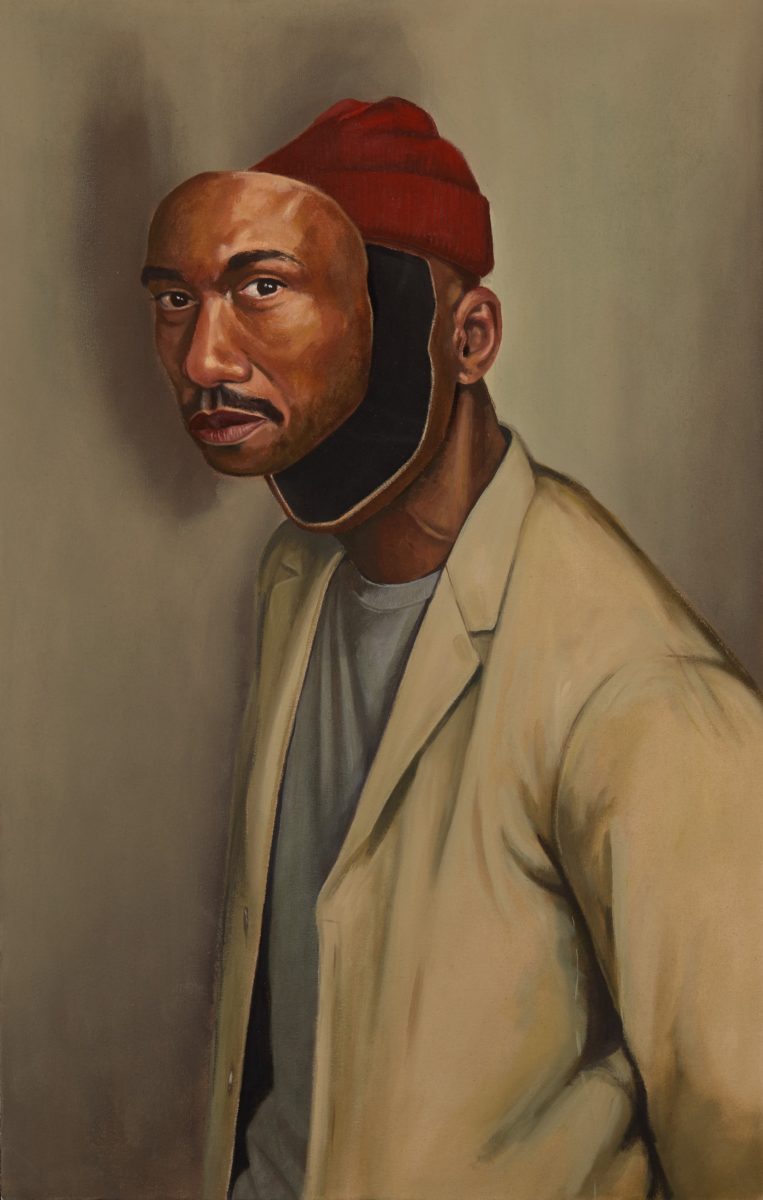

Another Me: The Koestler Arts exhibition 2019 at Southbank Centre. Courtesy Koestler Arts

Fiona Curran is director of arts at Koestler, and recognises Cutter’s experience of finding validation within his art practice. “I did a fine art degree myself; making things and being creative is really important to me, but I wouldn’t say it’s what I need to stay alive,” she reflects. “Many people making art in prison have said this to me in a literal way, and that is a humbling concept for many artists who work in these settings”.

Her words make me think about what it takes to become an artist in the UK. At the very least, most people who end up with a creative career will have received some encouragement along the way—perhaps from a parent or teacher who told them that what they had to say mattered. Of the many privileges associated with pursuing a creative career, this is perhaps the most fundamental. Compared with the experience of inmates, who describe never having received this positive reinforcement, their decision to make art constitutes a radical act of self-belief.

To understand how most prisoners in the UK might first connect with art, it is helpful to know a little about what prison in the UK is like. At the end of March 2018, the prison population of England and Wales was approximately 84,000, of which around 4,000 were women. Despite the fact that crime levels have remained fairly consistent (and, in many categories, have actually fallen) the prison population has increased by sixty-nine per cent in the last thirty years.[1] This might seem a strange correlation, but when you dig a little deeper, it can be explained by the introduction of new laws and the imposition of longer sentences, both of which contribute to this dramatic rise in prisoner numbers.

“Over a quarter of the prison population in England and Wales are from Black, Asian and minority ethnic backgrounds”

Such measures tend also to be punitive along class and ethnicity lines: for example, the 2019 Conservative manifesto included a paragraph that promised to criminalise previously legal behaviours of people in the Gypsy and Traveller communities. Over a quarter of the prison population in England and Wales are from Black, Asian and minority ethnic backgrounds, almost three times the representation in the general population. The fastest growing age group in UK prisons is the over-sixties, most probably a testament to the increasing lengths of sentences.

While right-wing headlines squawk about prisons as holiday camps, it is sorely evident that conditions are declining, with practices of extensive solitary confinement on the rise to deal with overcrowding. Opportunities for education and work have been reduced, and episodes of rioting have become so drastic that the government has been forced to intervene. Prisons are often tense, violent places where showing vulnerability can be dangerous. It is under these conditions that inmates may encounter art for the first time in their lives.

Luke Beech is an artist who teaches at Humber Prison; he remarks that the transgressive potential in art can have particular appeal: “Lots of offending behaviours are inherently creative and expressive. We offer a safe and meaningful outlet for all that”. Working at the prison has had an impact on his own performance practice, which involves feats of duration and discomfort: “I have picked up a few vernaculars and techniques from the prison, which is the ultimate low-tech environment”.

Art programmes in prison such as this have ancestry in radical projects of the 1960s and ‘70s, when the transformative possibilities of art and therapy were tested. Glasgow’s Barlinnie Prison Special Unit became famous with Joseph Beuys’ friendship and collaboration with inmate Jimmy Boyle, which explored the creative potential of art to “shape society and politics”. Beuys later went on hunger strike and took the Scottish Office to court to protest Boyle’s transferral to a prison where he was not able to make art. Art institutions continue to work with participants based in prisons. HMP Grenden’s partnership with Ikon Gallery in Birmingham places an artist in residence for three years at a time. Women at HMP Send were recently involved in an initiative by the National Gallery to tour a painting by Artemisia Gentileschi that relates to retribution.

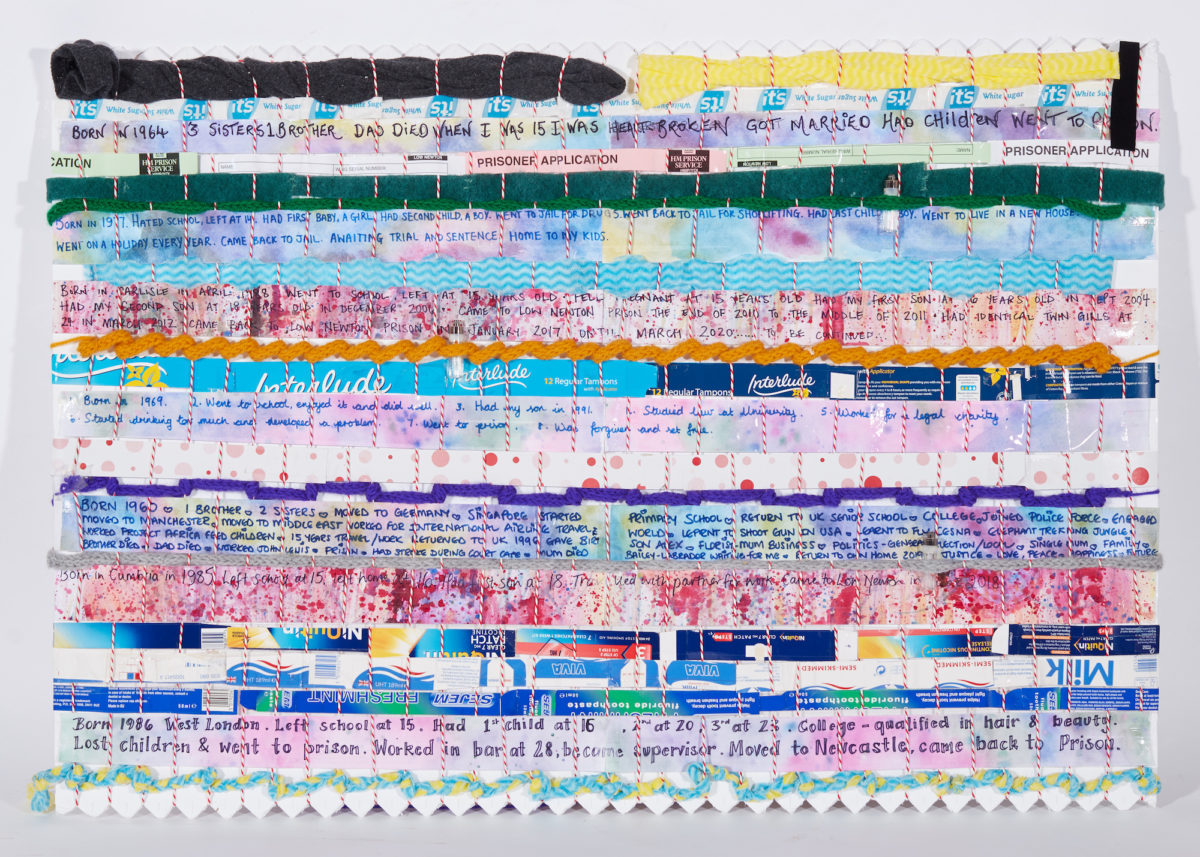

Women account for less than five per cent of the UK prison population, and the institutions holding them are more sparsely located across the country. While they are more likely than men to go to prison with dependent children, they are also more likely to be held over 100 miles away from their family. According to the Ministry of Justice, the rate of self-harm in prison is nearly five times as high for women than men. The closure of Holloway Prison in 2016 attracted strong criticism, and a campaign effort from Sisters Uncut drew attention to the gender-specific issues that face women in prison.

“Prisons are often tense, violent places. It is under these conditions that inmates may encounter art for the first time in their lives”

Holloway was famously where many Suffragettes were incarcerated; it was the setting for the production of textile-based protest art in the struggle for women’s right to vote. In 2018, Lucy Orta undertook a commission from Historic England and London College of Fashion to commemorate the radical heritage of the prison. She programmed a series of workshops with women at HMP Downview, where many of Holloway’s inmates were transferred. Prisoners in the UK are not allowed to vote—a controversial measure that has attracted criticism from the European Court of Human Rights. Orta centred her work with the women around their opinions on this parallel, and the resulting banners were publicly paraded inside and outside the prison.

In the UK, the prison system not only removes physical freedom, but confines individuals within a highly constricting identity that holds on well after the sentence is served. A criminal conviction chokes employment options, and the social shame attached to serving time can drag on for a lifetime. It can be difficult to feel concern for people who have made decisions that caused pain and harm to others. However, most would surely agree that, ideally, the systems we pay taxes to uphold would enable and encourage people not to repeat those decisions.

The rate of recidivism is very high, with seventy-five per cent of ex-inmates reoffending within nine years of release, which suggests that prisons are simply hiding, rather than resolving, a problem. In a society that refuses to recognise you as anything other than “a criminal”, the availability of art programmes may offer one of the most important routes to helping inmates renegotiate their own identities.

Prisons are designed to be overlooked by society, but they are civic organisations like schools or hospitals. They carry a unique and complicated responsibility balanced between punishment and care; all who I spoke to were clear that access to art has a vital role to play here. On entering prison, nearly thirty per cent of prisoners in England and Wales are assessed as having a learning disability or difficulty. A quarter spent time in care as a child, and twenty-nine per cent of men report having experienced abuse; for women, the figure is fifty-three per cent.

“Prisons carry a unique and complicated responsibility balanced between punishment and care; access to art has a vital role to play here”

The arts are increasingly removed from state school curricula in favour of more “practical” subjects, a principle which impacts poor people and people of colour disproportionately. Both of these demographics are overrepresented in UK prisons, and so there are questions to be answered about what connections there may be between limiting the options for self-expression, and the willingness of the state to see these issues replicated in prison settings. If access to art can have such an important impact on the way a person views themselves, and if producing creative work can offer a route to personal confidence and validation at our most vulnerable moments, why are we making it more difficult for children to find these opportunities in their lives?

In recent weeks, concern has been raised about the measures prisons are taking to minimise the danger of contagion inside prisons. A government statement that “low-risk” prisoners should be released to alleviate overcrowding pressure was quietly reneged upon: of 4,000 eligible inmates, only fifty-five have been released at the time of writing. It’s difficult to find out exactly what might be happening, but those I speak to agree that “lockdown” in prison likely constitutes twenty-three-hour solitary confinement. For Lee Cutter, who mentors an artist currently in prison, it raises serious concerns: “In prisons it is so easy to be forgotten by everybody. That place becomes your world.”

All statistics in this piece are taken from the Bromley Briefings Factfile