This feature originally appeared in Issue 30

“Of course, I would love it if there was no copyright law,” remarks Thomas Ruff drily. “It would make my work much easier.” Sitting in a side room upstairs at David Zwirner gallery in the heart of Mayfair, London, the German artist is responding to a question about the perils of working with archival imagery. He has long incorporated found images into his work. In his 1990–91 series Newspaper Photographs he rephotographed images sourced from German daily and weekly publications. And in jpegs (2004–07) he used images primarily found on the internet, enlarging them so the pixels broke up and made the images blurry. He has worked with everything from analogue photography to computer-generated imagery, scientific-archival, pornographic and wire-service material. So diverse is his approach to image-making it is impossible to categorize Ruff.

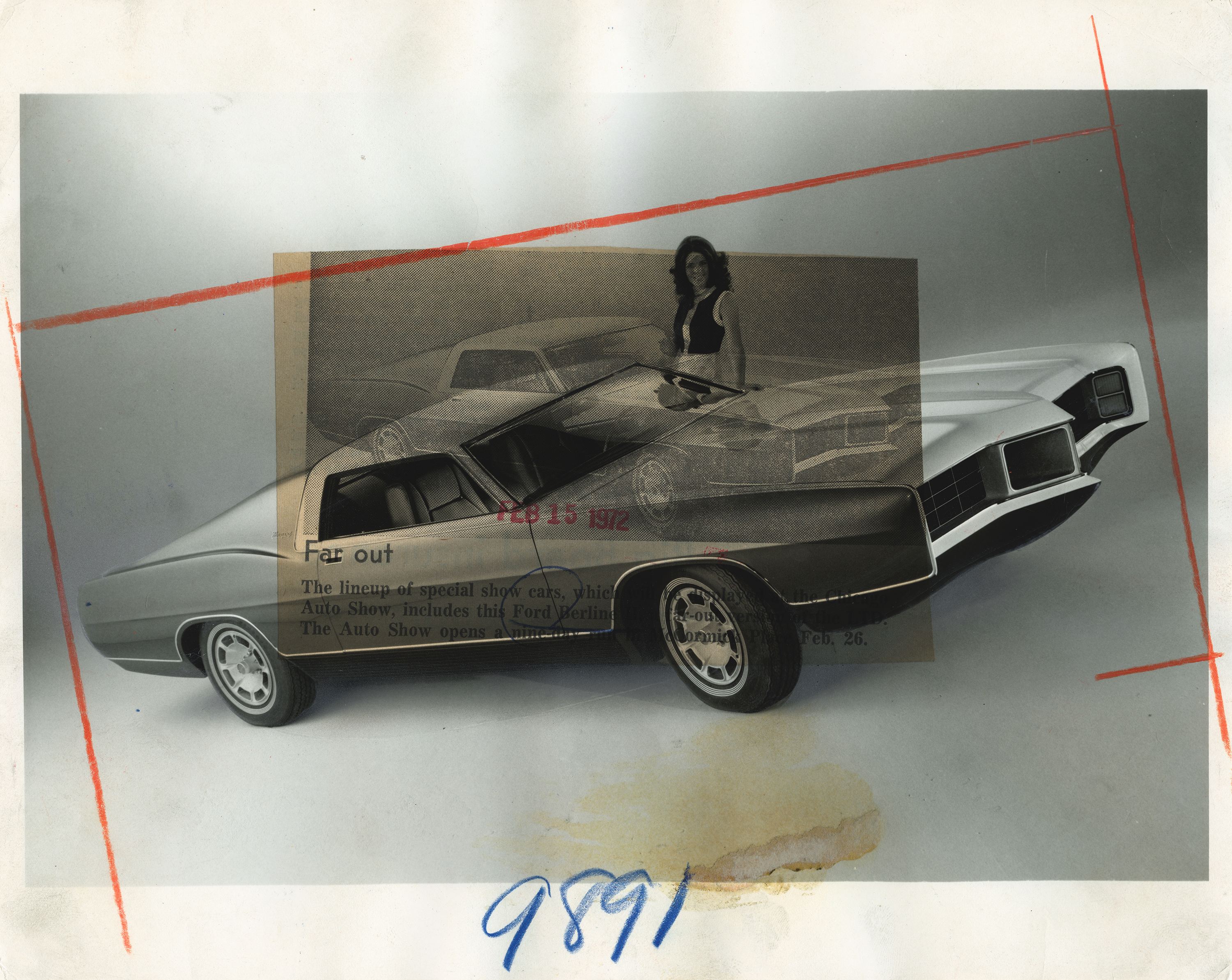

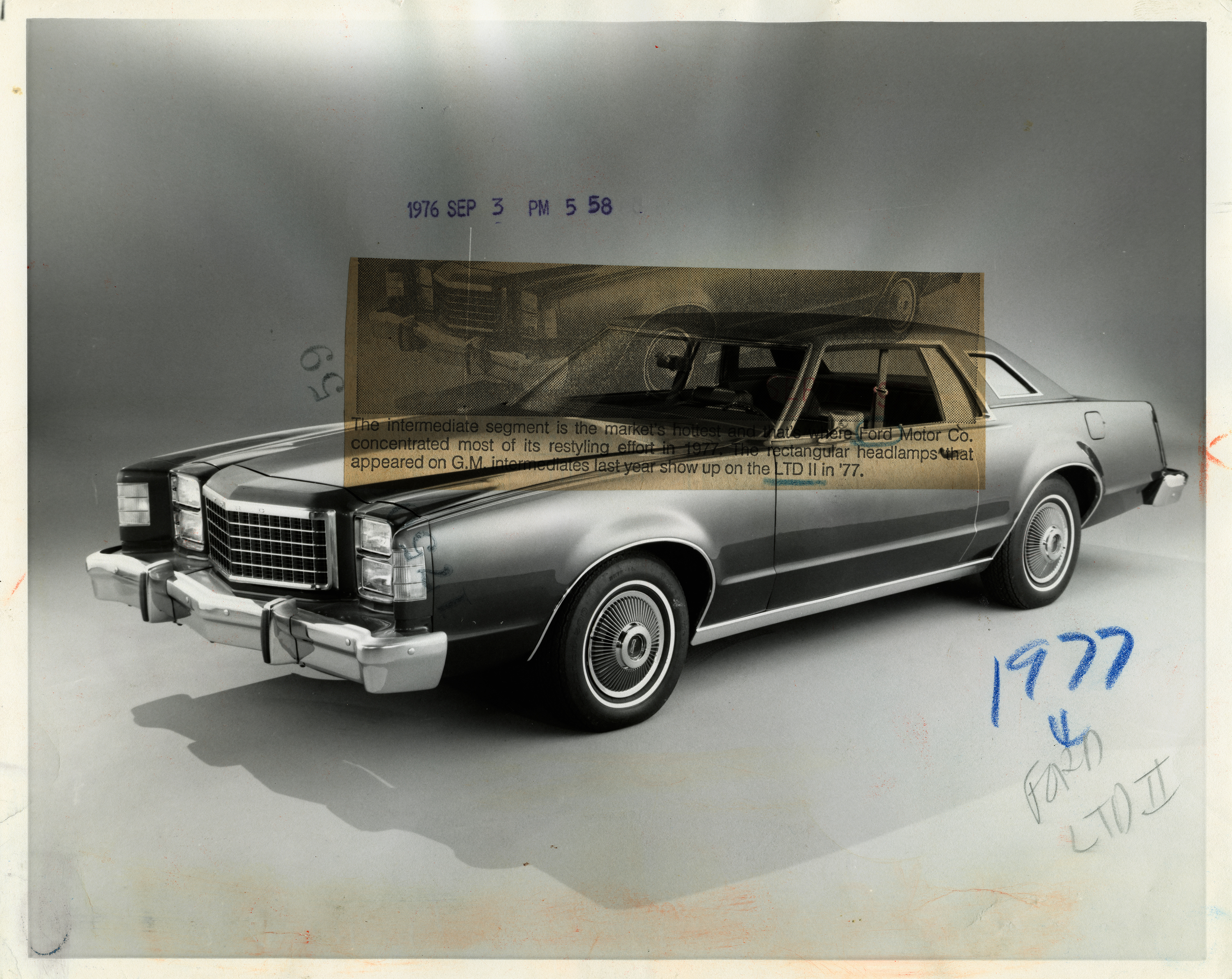

He is in London for the opening of an exhibition featuring works from press++. In this series he uses archival photographs that appeared in US newspapers, scanning and digitally combining the fronts and backs of the physical source images to create new images that seamlessly merge image, text and editorial markings. The first instalment debuted at David Zwirner’s New York gallery in March 2016 and saw Ruff use images from the NASA archive. He explains these images aren’t copyrighted, implying it allowed for a freer working approach. Some are included in the London show alongside images of cars, car crashes and Hollywood stars taken from his collection of American newspapers. He reveals it is necessary to license the Hollywood images from the likes of Getty Images. And Andy Warhol used one of the same car-crash photographs, he mentions casually. How strange to knowingly tread where another artist has been. Why do this? “It’s interesting for an artist to compare his own work with art history,” Ruff muses. “The challenge is to create a work of art that deals with similar issues… but differently. To update it.”

The artist, who famously studied at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf from 1977–85 under Bernd and Hilla Becher, is known for working in series, in keeping with the approach of his contemporaries in photography at the time who were intent on exploring subjects serially. Ruff shook up the art establishment in the late 1980s with his detailed and highly realistic yet strangely neutral-looking large-format portraits, and has been innovating ever since. I wonder whether he regards his work to date as part of one cohesive whole, what we might call his life’s work. “No. I’m just an ordinary man living my everyday life. I stumble upon something, and I think, ‘What is this?’ And I start working. It’s just what takes my attention.”

Ruff uses the analogy of trains on tracks to explain his approach. “Normally I’m working on a series that is already on the rails and then I have an idea for another one, which I start investigating—sometimes it takes half a year, sometimes two years to develop. The other series dies away and I already have an idea for something different, so I start investigating again… Some trains stop; it’s ongoing.”

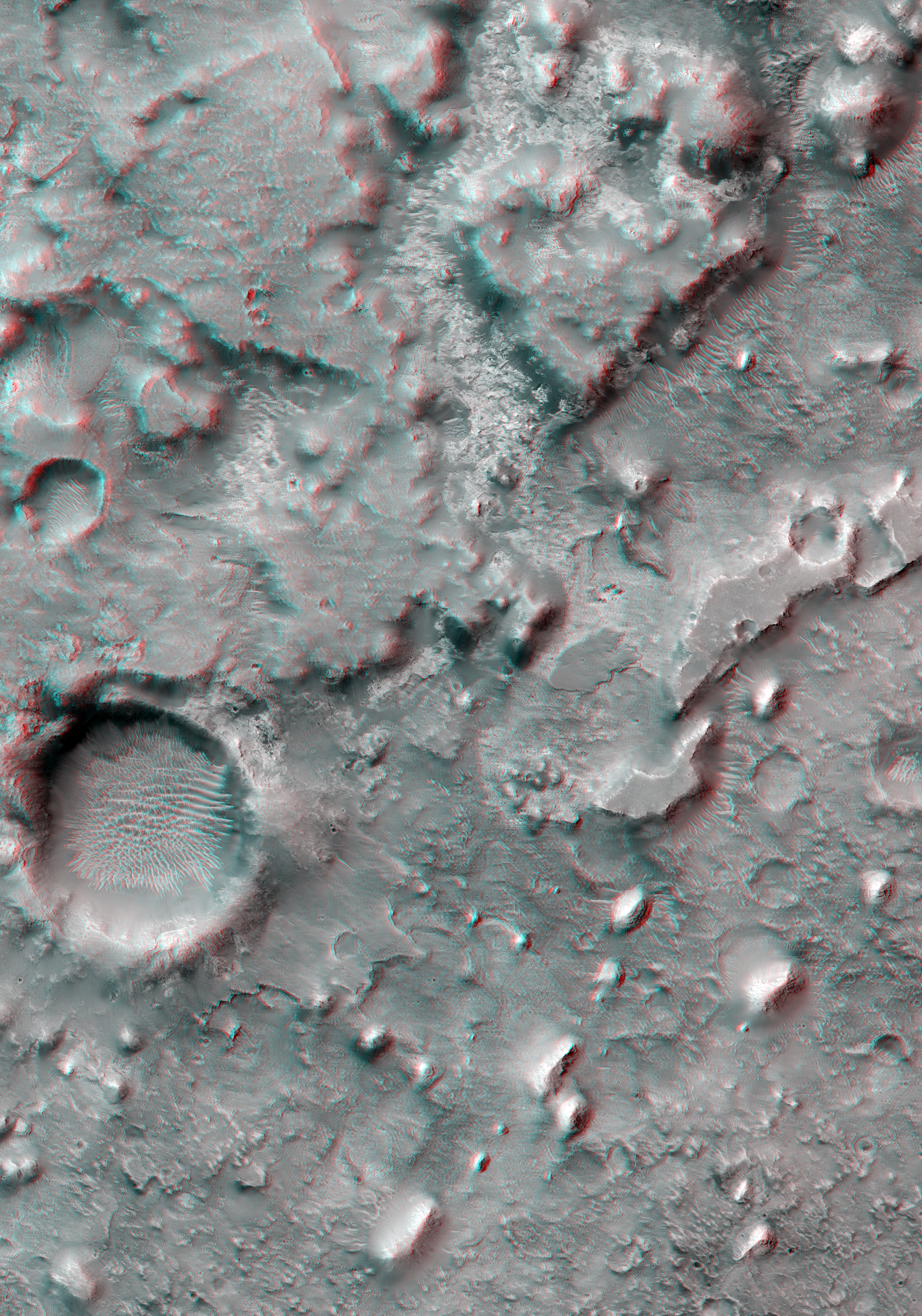

Towards the end of 2016 Ruff was shortlisted for the Prix Pictet, an award that promotes sustainability through photography. Work by the shortlisted artists will go on display at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London in May and then tour globally. The theme of this edition is Space and Ruff has been nominated for his series ma.r.s, based on black-and-white satellite photographs of the surface of Mars taken by a high-resolution camera on board NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. Ruff added colour to the images to make “the surface of this distant planet seem immediately accessible and almost familiar”, and rendered some images in 3D, viewable with 3D glasses. In his artist statement he comments on the absurdity of being able to see the relief of surfaces of another planet. When I ask about this idea of the absurd in photography he seems mildly amused at human attempts to develop technologies that will enable us to see beyond what our basic senses allow.

“Man is searching like crazy for devices to extend his vision,” he says. “So he created the telescope to see more of the night sky, and the microscope to see more details. If you cannot watch the surface of Mars from earth, shoot up a camera like NASA!” His tone is somewhat tongue-in-cheek. “You can say it’s a cheap trick, but it’s a great cheap trick,” he adds about the use of 3D technology. “Nobody has been to Mars, yet we have 3D images of the surface. I think that is absurd. It’s funny.” His face is completely deadpan. “I could cry from laughing.”

Photography’s potential to be deceitful pops into my mind and how we as humans have a tendency to take what a photograph is showing us as real. I put this to Ruff, who has often spoken about the truthfulness of photography and its objectivity, or lack of it, and whose work tirelessly seeks to deconstruct the photographic image in order to question the construction of meaning. “The camera records what’s in front of it, but that’s the only truth,” he says thoughtfully. “As soon as the person turns the camera, it’s his interpretation. But the machine itself is objective… Can you trust the image or is it completely authored and manipulated? Those ma.r.s images look very realistic but of course they are completely fictional. Right now this is a big problem in contemporary photography.”

Scale is another persistent concern in Ruff’s work and I wonder—why this enduring fascination? For Ruff, the reason is simple: at the time he was making his large-scale portrait images no one had thought to make big photographic prints, and because he could, he did. “When I started studying photography, most photographers said the best medium was the photography book. But they did not have the chance to make an exhibition of their work because there were no galleries for photography. Then came my generation—in Vancouver you had Jeff Wall, and Cindy Sherman in New York. Technology had developed so we could easily make big photographs. When I saw my first big portrait photograph I was surprised how it was a completely new image. The physical presence of the photographic work had changed. I guess Wall and Sherman had similar experiences. We wanted our work to have a bigger, physical presence.

“I think the big size has a lot to do with the emancipation of photography in contemporary art. If we had continued at this size, it would have been said, ‘Nice photographs’, but with the big size, photography finally was accepted as art.”

He points out that not all of his works are large, adding that increasing the size of the print should be done for a reason. For the images in press++, for example, it was important to show them large so the marks and handwriting stood out. “My initial idea was to print the photographs at the same size as the originals, but to show all of the details, to understand how the stab went into [the photograph] I needed a larger size. So I made two sizes.” It’s interesting that you mention “stabbing”, I say, as it seems there is a brutality in the way the marks were made by the news teams . “The photographs were treated without respect,” says Ruff almost critically. “They were working material for the editors [who] were only thinking in terms of publishing those images in the newspaper. They had no respect for the photographers, and they didn’t care about the photographs.”

Standing back from the walls at David Zwirner, the prints appear majestic and beautiful, and dominate the space in such a way as to almost become sculptural. What were once discarded press images have been brought to life again in an entirely new way. Is this art for art’s sake, or is Ruff intent on commenting on the way we live today and photography’s role within this? “I can’t explain the whole world,” he says a little curtly. “I am just a heterosexual German male who is watching the world, and this is a very limited view. I don’t want to be an explorer or enlightener. I don’t want to tell people how they should live. [And] I don’t insist on my view of my work. It’s a proposition. People should look at it and then make up their own minds. Some [views] fit with what I think, and others are the opposite, but that’s fine because I’m only one of billions of inhabitants of this earth.”

Images courtesy the artist and David Zwirner, New York/ London