Adriana Varejão addresses cultural histories — created, borrowed and imposed — in works which follow the Baroque tradition of parody. “The Baroque universe is about representation, not about the thing itself,” the Brazilian artist says. “I would like to recreate this kind of game.” Varejão is about to show Azulejão at Rome’s Gagosian.

The tile pieces for Azulejão have been created for the specific space of Rome’s Gagosian. Have you spent time in the space while making the works?

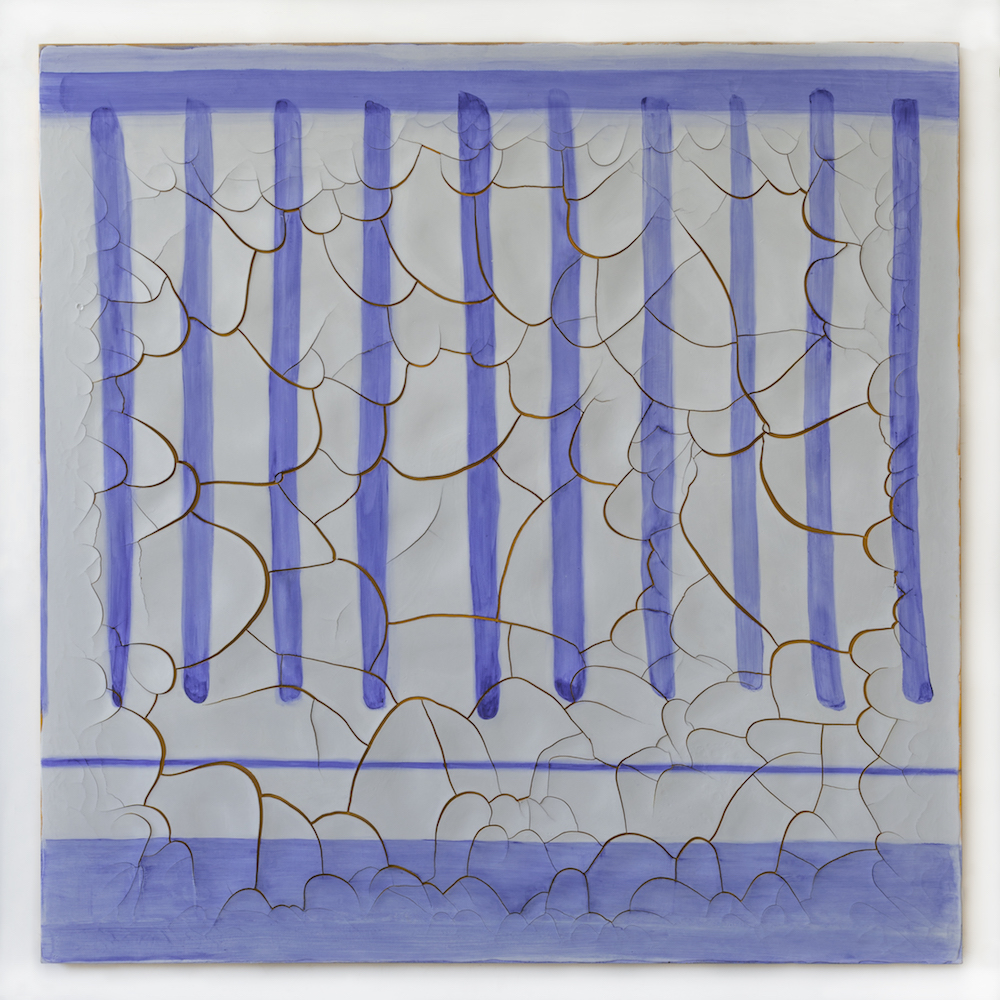

I’ve been to the space. It’s very special, it’s a round space; oval. I’ve never been to a space like it. It’s very minimal but it has this very beautiful shape, and it also has windows with natural light. I made all the works square and the same size so they will be installed in a very symmetrical way around the space.

This is the first time the tiles have been created to this scale…

Yes, normally I’ve installed the tile pieces with many, many works. I made this huge installation which has a permanent view in Inhotim, the park museum in Brazil. The work there is composed of 184 square paintings, but it is one work. So the overall scale isn’t much bigger, but they are individual pieces. I have an archive of many images of tiles that I photograph in Portugal and in Brazil. They’re tiles that were produced in the 17th, 18th and 19th century, so they’re blue and white, and they’re baroque. From these I select the images that function individually.

What set off your interest in the tiles. Is it something that you have always been surrounded by, or did you come to them through research?

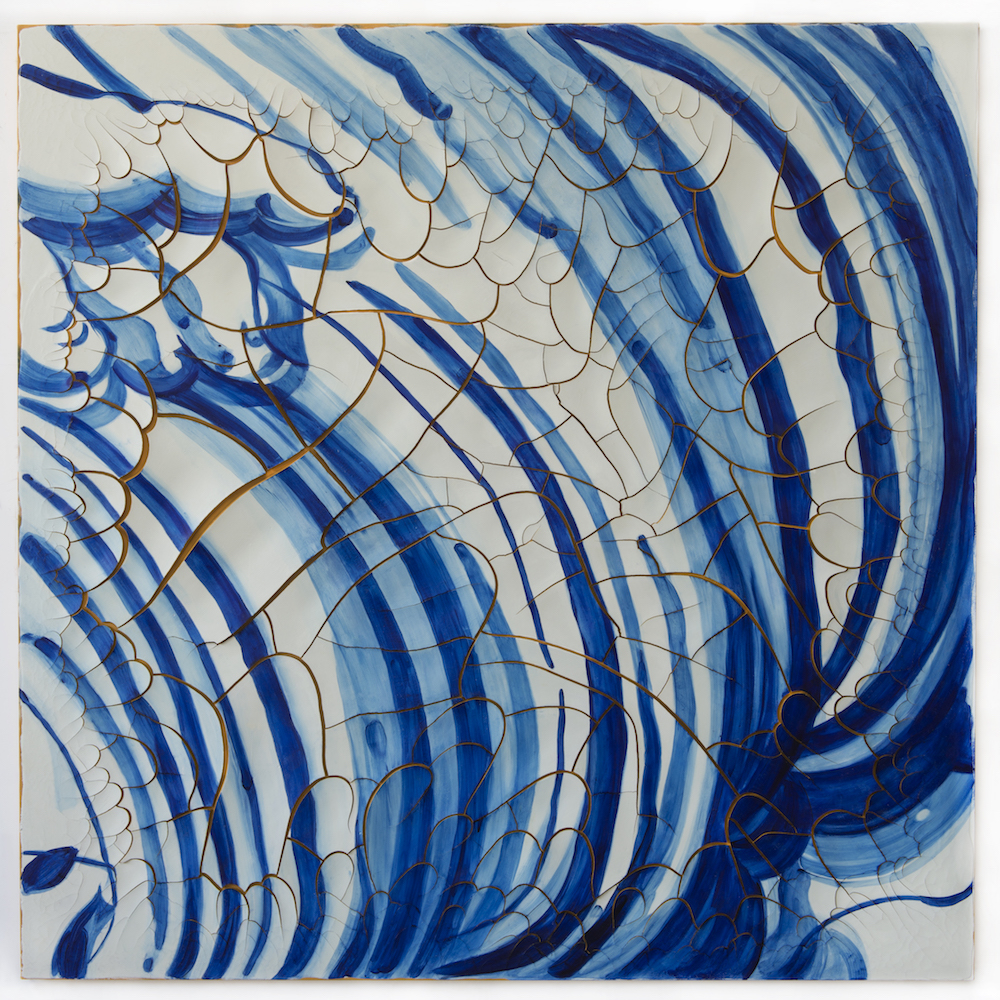

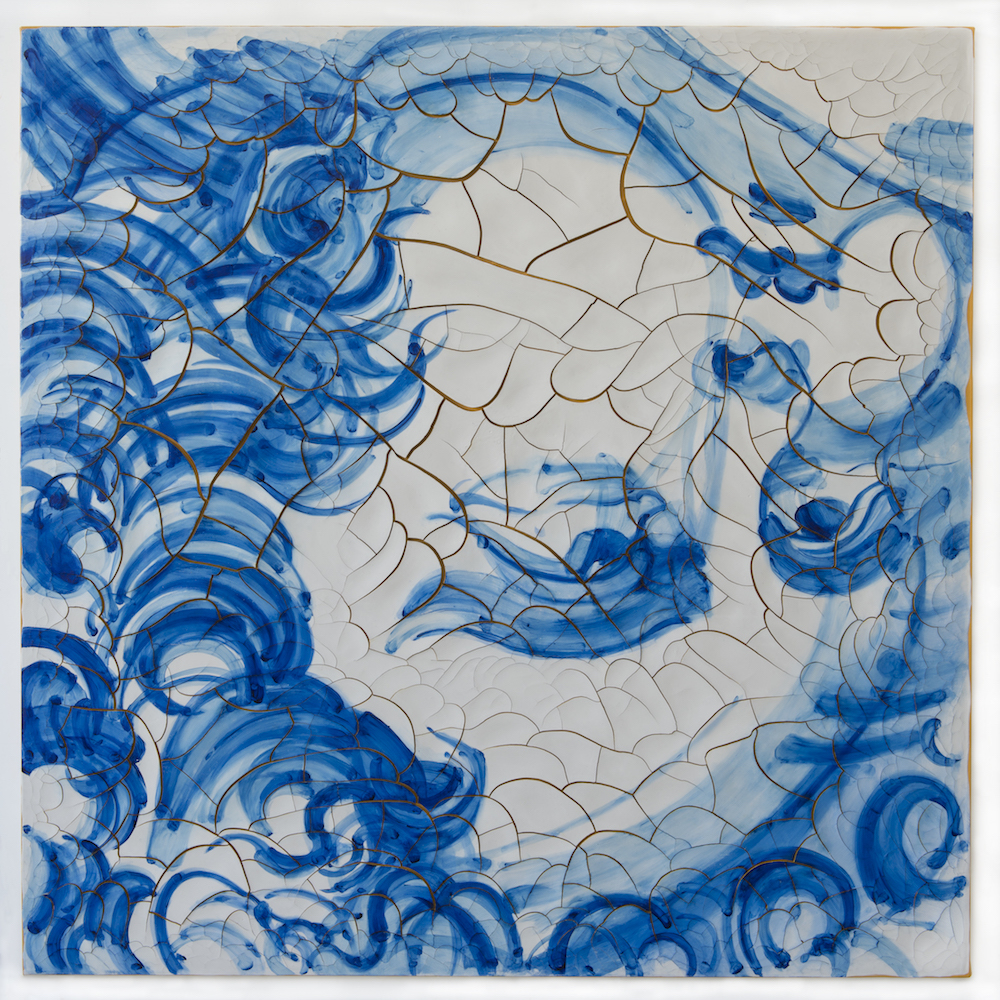

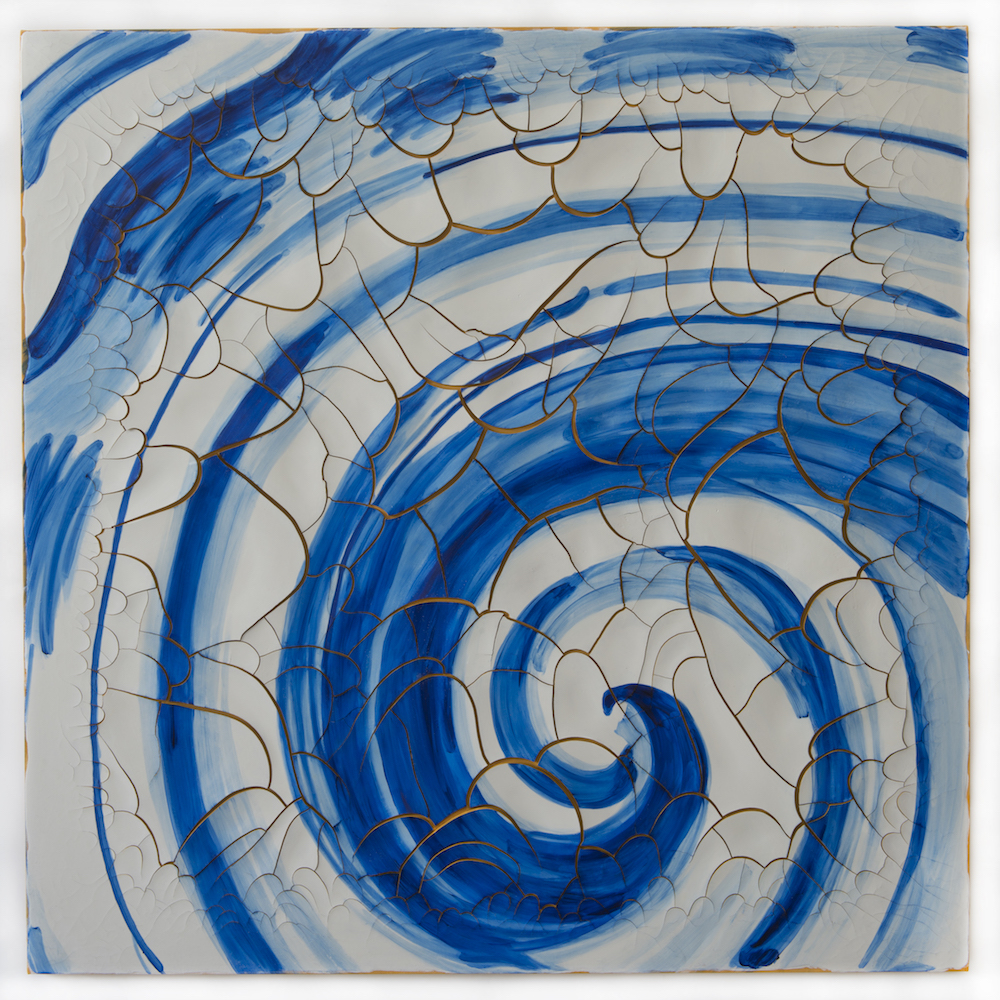

I was interested in Baroque since the 80s. I have a painting of tiles, the first one is totally different from these. I worked on the images of tiles in the 90s, not only these ones, sometimes monochromatic tiles. I have a work that was bought by Tate Modern, it’s a huge work with monochromatic tiles. These tiles that I’m going to show, they look like objects, they are almost three dimensional because they have this cracked surface. It’s like reconstructing a physicality that reminds me of the ceramic surface. It’s not only about painting the image.

What was behind the decision to explore them as paintings instead of ceramics?

I am a painter in the end, it’s my filter and denominator. And technically it would be impossible to burn tiles this size. Also because I think my work is about parody and not about the real thing. I often paint meat, I’m trying to recreate three dimensional meat — but I don’t use meat. I’m much more about the representation that we have in the Baroque. The Baroque universe is about representation, not about the thing itself. It’s theatre and parody. I would like to recreate this kind of game. Especially for Rome.

Do you enjoy if there’s a point of confusion then? That someone could experience these works at first as something they’re not?

Yes. It was funny, I was with Louise Neri — who is the director of Gagosian, she published a book of my work fifteen years ago and since then we have been in contact with each other and we have a very strong relationship through the work — at a very famous Baroque church in Rome and we were looking at two columns. One column was painted as marble. Alongside this column was another made of marble itself. So one was painted and the other was real. We thought the painted one must have fallen down and been reconstructed, but this must be impossible, the church would fall! I asked an art historian in Rome and he said: No, it’s just the pleasure of the game. It reminds me of a work by Vija Celmins; she has small stones and she paints them exactly as the originals. I’m a big fan of her. It’s about the same thing, this very traditional thing about Triboulet and games. I think contemporary art now is so far away from that because it has this ethical thing about the material, you cannot lie. Everything is about the truth. I’m feeling a little bit nostalgic about the fiction.

You work with cracks and tears a lot in your work. When we last interviewed you [Elephant 16, Autumn 2013], the material coming from the cracks was a lot more graphic and violent feeling than these tiles, with meat and flesh coming out. With these new works, the cracks aren’t so graphic. Do you feel something’s changed for you?

Actually we have a work with meat also in the show. I have a ruin and it will be in the entrance to the gallery and actually it was the last work I finished, but I changed the way of painting a little bit, it’s a little bit unfinished, so in my new ruins I’m revealing the game.

Do you have quite a strict process when you’re working? Do you know where you want the pieces to end up visually and physically?

The cracks I can’t control because they crack the way they crack. Sometimes I throw them away and sometimes I see something I didn’t expect. So the cracks are made by this invisible artist. It’s like a force of nature when it dries and I can’t control it; I like that. But the images are based on research. I don’t invent the image of the tiles, I just curate them. It is much more a process of editing than creating. There are so many images in the world and I like to recreate history, so I go to the past and give a new meaning to those images.

Is your research very visual, or do you also do a lot of historical and academic reading?

It’s much more visual but I like to read sociology and history. Actually two years ago I wrote a book with a very important sociologist in Brazil called Lilia Schwarcz. She was one of the authors who I used to read in the 90s, I was a big fan of her and then once I met her and said we should do something together. Ten years later we developed this book [Pérola Imperfeita]. I was explaining my process and research to her, and she was getting the references and giving this academic background to it. I’m much more crazy and free and I go from 19th century to 13th century, I don’t have a very rigid process and I make totally crazy connections. One of my references for the cracks was Chinese ceramics from the 11th century — Song ceramics actually, there’s a brilliant collection at the British Museum. It’s very poetic, not only visual but poetic.

I suppose so much of your work is about cultures borrowing from each other anyway, so even though the connections you’re making might not be formal, perhaps at some point they have existed?

Yes, the tiles in Portugal are blue and white because of Chinese ceramics that came to Delft in Holland, that then went to Portugal. Islamic tiles were polychromatic, green and yellow, and then this huge blue and white range of tiles came because of the Chinese ceramics. And then I make totally new connections again.

When you’re showing outside of Brazil — as you are now in Rome — do you feel there’s a different meaning on the work, when it’s shown in a country that doesn’t have such direct roots to the subject matter?

Sometimes it’s very hard to show work in the United States, for instance, because they are very closed to history. Sometimes people don’t know the history of tiles in Portugal, they don’t know that it exists. I think in a Catholic country it makes a lot of difference. So in Spain, Portugal, Italy, even France has something. But the United States, Germany, England, there is not a Catholic background, the Baroque. It is difficult in these places. But anyway, we are in the contemporary art world and I think the work should survive, from different paths, different ways of reading the work. The history of painting, abstraction, form, colour. It’s not only conceptual, it has a concept in the background but it’s not totally attached in the concept.

You work with a lot of different cultures from a historical standpoint, but how do you feel about globalisation now, in the 21st century mixing of cultures. Is it something you find problematic?

It depends. Globalisation is problematic when there is a culture that dominates. It’s much more about imposing one culture on another, and that’s a big problem. The nation which controls the media imposes their culture and the smaller one doesn’t survive. I think in the old times there was a melange of cultures. Brazil has a very good lesson to teach because here we have a mix of cultures; with Africa and the European culture. All these cultures survived and became Brazilian culture. Brazil became a very rich country in terms of culture and we have this very interesting flavour but here we don’t have ghettos, the Europeans and the Japanese became Brazilian in the first generation. That’s what I feel is so different from other countries. In the United States people still have this background; Japanese, Russian or whatever. They have neighbours who speak their language, it takes many generations to mix.

Adriana Varejão ‘Azulejão‘ is showing at Gagosian, Rome from 1 October until 10 December