Last November, British artist David Raymond Conroy joined Zabludowicz Collection’s inaugural residency in Vegas. ‘You gradually feel yourself more in a bubble because people have to come to you,’ the artist says of working for long stints abroad. ‘I think that’s an interesting experience, if slightly infantilising.’ Conroy’s work is currently showing in the gallery’s latest group exhibition, Emotional Supply Chains.

Can you tell me a little about the work that you’re showing in Emotional Supply Chains?

There is this compulsion element in Vegas that is very present and I was interested in making something that contained that. I was reading that slot machines are vastly the biggest earners in Vegas. What I found interesting is that 75% of the people who attend Gambler’s Anonymous are slot machine gamblers. They call it ‘the machine zone’, and they say that really hardcore slot machine gamblers don’t like to win because it disrupts the flow. Sometimes if they see someone win on a machine they will purposefully move to that machine. The way slot machines are designed is something that I was thinking about in this work, and it’s the same for HBO series or addictive podcasts, it’s the ‘partial win’. More or less, on a slot machine you will win, but only a bit. You’re winning but you’re also losing, which is the thing that adds to the compulsion of these TV series. A Dan Brown novel is very similar. It gives you two puzzles, solves one and then gives you a new one. You’re constantly winning and losing. You’re on a cliffhanger but also being rewarded. I have no relationship to gambling of the style that is in Vegas, so I was trying to think of my own things that have this compulsive element. I wanted the work to feel like a TV series, like that feeling of watching—I call it junking—a series where it’s just back-to-back episodes. But the heart of the video is—well it’s the heart or the MacGuffin, however you’d like to look at it—about wanting to do a project about homelessness in the States and trying to decide how to do that.

Did the decision to explore homelessness come directly from being in Vegas, or was it something that you’d been thinking about beforehand?

No, it was totally something that came from Vegas. I think a lot about morality and ethics, and wanting to get this thing that I call the ‘empathy leap’. As though you are in someone else’s position. I have very little knowledge of America, but it seems like homelessness—especially in major cities on the West Coast, perhaps because of the climate—is at a level that I’ve never witnessed before. That is a shocking thing to see, especially in Vegas because of what Vegas is. It’s party town, there is a really hard juxtaposition between watching people enjoying themselves—or wasting money, however you want to look at it—and then you go outside and someone will ask for a dollar and they get called a piece of shit. I can’t drive so my experience of America is a very peculiar one. Often I’m on foot or getting public transport, and it seems that if you’re walking, you’re homeless. I guess that’s the reason to make a bit of work about it, because it feels crazy to me. But then there is the feeling, especially in America of: it’s your money so you can do what you like with it. If you earned it you can set fire to it.

There are quite a few of your fellow Vegas artists showing in Emotional Supply Chains. Did you know how the exhibition would be tied together, or were you making work on your own tangents?

Well Paul [Luckraft, Emotional Supply Chains Curator] had the idea for the exhibition long before I was invited to do the residency. But, to be honest, for me this relationship between emotion and—for want of a better word—technology, is something that interests me. I’m not specifically interested in technology, but I am interested in contemporary life which includes technology.

I’ve read that you’ve previously spoken about the artist as tourist, and I wondered if that is a positive or negative slant for you? The term ‘tourist’ can hint at a disconnection with the heart of a place.

I really believe in fundamental ambivalence, I can’t imagine a response where ambivalence isn’t the appropriate answer. But I think a new place gives you new eyes which is an incredible experience, and at the same time you are very much in a bubble. You are never really there. As a person who goes on residencies, often for a long period of time, especially often not speaking the language, you gradually feel yourself more in a bubble because people have to come to you. I think that’s an interesting experience, if slightly infantilising. I think America is fascinating, what is the phrase: ‘two nations divided by the same language’? I have never been anywhere where I’ve felt more European than America, I am totally unrelated to America.

Language is such a big part of your practice too…

My parents are Irish and I guess I come culturally from a story-telling, pub-anecdote world—which culturally is really important to me. Then also stand up, cinema and fiction play a part. It seems interesting to me, and a good way to make work. For whatever reason, technical language is fascinating to me. How things work is something I think about a lot. Even if it’s thinking about how a TV series is constructed, or how marketing language works. Or just thinking about how foreign language translation works. It’s something about the technicality of language and emotion; whether it creates a desire or a longing or a sadness.

You often employ the language of the internet too, which has warped language as we knew it in many ways, both emotionally and technically.

I think it has changed a lot of things, the way that things are spelled and done online is the thing that you see, but I think that’s an accident. Something that’s crazy to me is way that the internet is all about broadcast–it feels like it’s so little to do with conversation and so much to do with broadcast–and also the contemporary trope of the huge middle man–Uber is the biggest taxi company and it doesn’t have any cars, Facebook is the biggest website and it doesn’t have any content—where the machines only function with content and nothing can provide that content at the speed that it’s needed apart from lived experience. The only thing that can fill it is lived time, because nothing can be produced fast enough. I think that the birth of this real-time phenomenon is marked. It’s an accelerated lived experience. When you watch these lifestyle bloggers, they cut the ends of their words off too early, as if they were reading two paragraphs with no breath in between. There is no content, there is no editing of content, it’s just editing of space. Their content is unclear and mucky. It’s interesting that alongside that there’s been a resurgence of Bildungsroman, something that seemed to me to be a nineties, postmodern trope of the first person, perhaps slightly unreliable narrator. Even though they might appear to have nothing to do with one another, they seem to me to be very tightly connected. We’re bred culturally to want something that is right, for right now. For some people this lifestyle blogger thing works, for someone else it might be Elena Ferrante. Somehow they speak to a similar need, but they are expressed in very different ways.

‘Emotional Supply Chains’ is showing at Zabludowicz Collection, London until 17 July

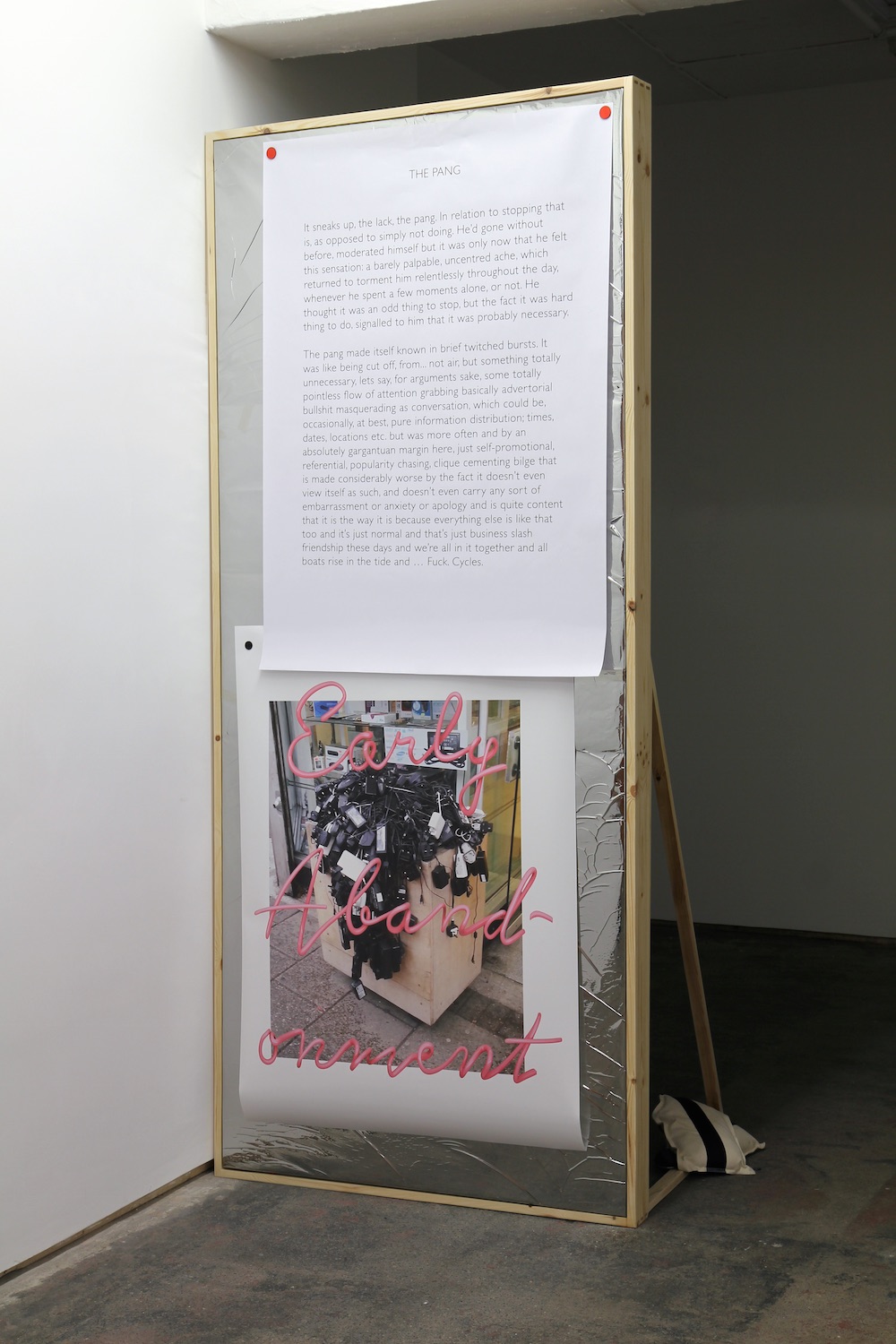

Untitled (Red, Orange), 1968. David Raymond Conroy with The Mark Rothko Art Centre 1968/2015. 300 x 400 x 80cm. Mark Rothko digital printed reproduction on Canvas, (172 x 130 cm), one-sided freestanding wall