It’s Brat Summer and the chances are that you’re familiar with Charli XCX’s ‘360’ and the lyric “You gon’ jump if A. G made it.” A. G. Cook is, of course, Charli’s producer. But he is also an artist in his own right. In her latest article for Elephant Magazine Fabiola Talavera sits down with A. G. Cook to discuss Britishness, the practice of world building and the return of Pop.

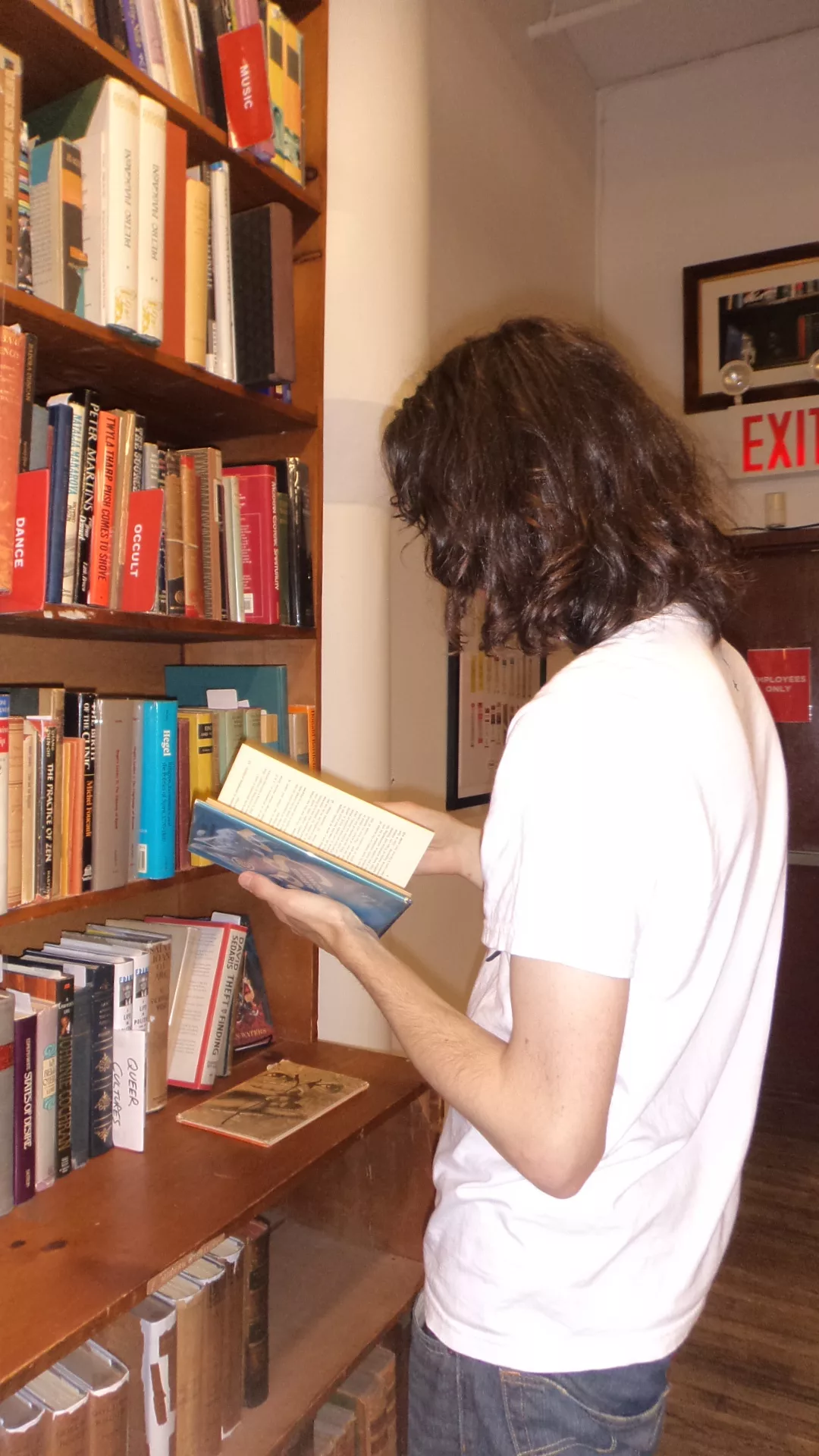

After spending some time in the quiet Montana grasslands, British music producer A. G. Cook teleported himself to New York City for a few days at the end of June to headline LadyLand festival in Brooklyn, a rave-like celebration under a bridge where he played an upbeat mix of hits produced by him from the early PC Music days, Charli XCX’s Brat, and his recently released third album, Britpop. I met him for lunch the following day in a no-frills, tasty Hawaiian-Japanese restaurant in Williamsburg, where we found a more or less silent corner table to chat about his new production and shoot some portraits. We then took the L train to Manhattan and arrived at Union Square, where the overwhelming acoustics of this city confronted us: a security alarm was set off, screams were heard in different languages, and clusters of people bottled up in the entrance taking refuge from a heavy storm. The summer had kicked off with scorching sunny days, but this weekend the skies were grey and warm rain poured non-stop. An elegantly uniformed guard shoved us off the entrance of a building when we stopped to look for an address, “no loitering” allowed. Other intersections were friendlier, with fans vocalising their love for A. G. as he walked past. It was the end of pride month, and the streets were filled with queer flags, and crowds of people were trotting around in skimpy outfits and elaborate makeup. We made our way to a busier-than-usual bookstore where other partially soaked onlookers sheltered. “Suddenly, everyone is into books,” he observed. A good chunk of the afternoon was devoted to browsing pre-owned publications on art, design, history and mysticism. We then walked some more until we parted ways in the far end of the Lower East Side.

You’ve been based in the US for quite some years, moving around between California and Montana. What made you want to revisit your homeland for Britpop?

Being in Montana for a full year during the pandemic was the longest time I’ve been away from the UK. It’s so different from how I grew up that it made me realise all the things I take for granted, the eccentric and fantastic qualities about Britain. It’s pretty abstract whether we feel we’re part of a country or not, that ambiguity links to my interest in musical genres. “Is a genre actually solid or not?” A word like Britpop plays that double ambivalence. Not just because pop is very ambiguous, but because the word also relates to a historic Britpop era. There’s a biographical quality to thinking about the ten years of myself as a musician and the thirty years of myself as a person.

How does your view of Britishness relate to other British contemporaries you’ve worked with, such as Charli?

In a lot of ways, Charli represents Britishness more than I do. We didn’t have the same upbringing, but there’s a parallel. No siblings, an only child life, honing in on things in a different way. I was born a little too late for the OG Blur-Oasis Britpop wars; the turn of the millennium had more impact on me, especially a London-centric view of it. It was a very optimistic time; Tony Blair was elected, and the Spice Girls were big for our generation. Actually, the Spice Girls really connect to Charli’s musical attitude. It’s not like I was a mega fan of it as a nine-year-old boy, but it was so representative of the UK at that time. There was this futurist vision at that point, then came Brexit in my twenties and this whole crazy crash-and-burn journey of where the finances and politics ended up. I wanted to dig deeper than the London-centric thing into the different outlines of this island a thousand years ago, looking into the folklore, the prehistory, and pre-Roman times. Although, it seems irrelevant to talk about geographical borders nowadays with the Internet.

Sometimes, it feels like our generation grew up on the same stuff through the Internet. Even for a suburban Mexican girl like me, I was watching Skins on video-hosting sites that are now extinct, stuck on Tumblr, befriending other melancholic teenagers and uploading sleazy party pictures. Do you think the Internet is now a more diverse space for youth culture, or has the algorithm made it more one-dimensional?

I’m very nostalgic for the 90’s Internet. As a child, I had an au pair who was very techie; I remember her showing me html and forum-type things. It was a lot more based on imagination, the idea that we’d all be connected and be whomever we wanted through avatars, rather than projecting a version of ourselves on Facebook or Instagram and having profiles verified with IDs. I’m interested in the shift of these generations and the early versions of blogs like Soundcloud as places to genuinely meet people and find amazing music. It’s still quite mystical how you can message someone, hit them up for a mix, and end up with them playing club nights in different cities. The Internet has become a lot less exciting and extremely literal. In the early PC sites, you’d have domains that felt immersive and experimental; now, you have a very specific mobile experience where the default canvas is much smaller. I try to use tools such as chat rooms and bots, but it’s quite an effort, you really have to rally people. Whereas in the past we were all rallied into mysterious game environments such as Neopets.

We were shooting Alaska Reid’s ‘Back to This‘ music video in Los Angeles at the beginning of last year, and you decided at the last minute to wear a Union Jack sweater to play the drums. Were you already thinking about these themes then?

I’ve been planning this album and its campaign for quite some time to really understand its end goal and give it a banner.When we were filming Alaska’s video I knew this was coming but I was still exploring. I had this Union Jack jumper that looked cool and I had to do something with it. I’m glad that video kept it ambiguous by being black and white.

When I first saw the cover of Britpop, it really reminded me of the works of Bridget Riley and the whole Op-artmovement, was that intentional?

Definitely, I love all of that. There are already many versions of the Union Jack and I didn’t want it to feel that nationalist. One of the first things I did graphically with this album campaign was to ban red, white and blue. I worked with Timothy Luke to design a flag with those shapes but without the color scheme. I basically was like “Let’s make it more groovy.”

What were other British art and media references you were looking at?

All the sixties stuff, a lot of progressive rock album art. There’s designer-illustrator Roger Dean, who did all the fantasy landscapes for Yes. It’s very stylised and not fully illustrative. It has abstraction but also over-the-top post-Tolkien worldbuilding. When I was a student, I remember looking into the pencil drawings of Paul Noble, contemplating the mystery and the level of complexity in these endless isometric towns. Charles Avery also did The Island, this secondary world of inventions, a bit poking fun at the British Empire. A lot of that inspiration was used for Thy Slaughter too.

You studied for a bit at Goldsmiths University. Did that have any everlasting impact on your artistry?

I studied art briefly before I pivoted to music and computing. It was a blip year when I realised I had spent my time working on music but studying it in a quite zoomed out way. The sum of its parts interested me rather than just loving a melody or a good riff. It has to have a higher meaning for me to get into it. I hate when a record campaign has a very literal narrative, where it feels like you have to memorise a bunch of shit for it to make sense. You don’t need to create fiction for the atmosphere to be amazing. I’m attracted to the fluidity of forms with auditory, lyrical and visual experiences. I feel very comfortable with what I would call an artistic worldbuilding experience, or what Ian Cheng would call worlding, as the different masks we wear and how we interact with creativity. I think music is so fun because you can get under people’s skin before they’ve understood any of it. David Lynch’s Twin Peaks is so effective because, aside from the amazing music, things such as The Black Lodge have a dream logic that communicates without being restricted to one meaning or actually knowing the law of it. When I was young, I was drawn to these big, complex diagrammatic worldbuilding exercises, and as I’ve got older, I’ve enjoyed more atmospheric ones. Adding flavours but not making them too obvious- that’s the sweet spot that i’m constantly looking for, and it also applies in terms of how I collaborate with people.

It is now quite known that you like to set up Dungeon & Dragons campaigns with friends, even online, with participants in all kinds of time zones. Does this role-playing game, where you often act as the Dungeon Master, play a part in your general worldbuilding?

That interest for me pretty much blossomed in parallel with that pandemic lockdown era. Being isolated, I wanted to chew on something aside from music. Getting lost in all the D&D publications they’ve done since the ’70s, I’d find copies in thrift stores and online PDFs of early versions of the game that remind me of the early internet. Essentially people mailing each other photocopied zines with these amazing hand-drawn illustrations and asking each other to contribute to them. But running the game for real was a big breakthrough for me, because that’s when you realise how much of collaboration it is with the other players and how it deals with chance, having to roll a dice to find an outcome. It really had quite a nice therapeutic influence on my work. I’m not someone who’s improvising or jamming all the time, but I am taking risks and seeing what happens. The original D&D creators were based in America, and they were building this pseudo-historical fantasy of what the Scottish highlands or Victorian London looked like, so it’s once again that gap between America and Britain. Finding something written decades ago and inserting that into some modern idea was insightful. I can read some D&D things written recently and see what seed was taken from the ’70s version, but how it was also affected and altered in the ’90s as a response to video games. It’s very loaded in the way that any hobby is.

In terms of production, what was done differently for Britpop when you compare it to 7G?

The biggest difference was I figured out halfway through the process this idea of past, present, and future in three discs. I could then quite confidently double down on the atmosphere, not in the way 7G is by instrument, but by a general headspace. The first disc is sort of this almost utopian electronic music, looking back to the proto-PC Music I was making around 2012 to 2014 and using the new skills I developed to make music. With the present one I drove it with more lyricism, a lot of vocals, which were almost like a self-portrait of a specific moment. The lyrics that survived well were written almost entirely in one go. So I committed to that, and to not even re-record vocals later singing better. The guitar sounds here are blended with strange synths and pitch distortions in a way very much of its own, whereas 7G guitar sounds were more based on specific genres, that being folk, rock, or metal. With the future disc I went in all directions, kind of like a radio dial, but also as a response to the two other discs. I thought it would be interesting to give the feeling of time travel, in the sense that the future could be any of these things, while the past and present is carved out by my experiences.

For the release of Britpop, you created mock websites Wandcamp, Witchfork and Wheatport that gathered up known and obscure talents. By the time the album was out, the sites stopped operating as an “Undisclosed Multi-dimensional Conglomerate” bought them. Why did you decide to do a campaign like this rather than have a more conventional release?

It was a lot of work considering I was also doing shows in between, but I definitely enjoy pushing for an overload. I produce a lot, and I’m not always wearing my artist hat, so every few years that I do, it’s really “Go hard or go home,”pushing the threshold of what can be pulled culturally, not to mention physically or mentally. I was thinking about these alternate websites as a response to the slow entropy of the Internet. Many blogs I used to read don’t exist anymore andthere are fewer platforms and voices, let alone stuff like the Pitchfork merger. I thought it would be good for someone in my space (no pun intended) to feed a much more radical ecosystem where we’re already running a website, employing journalists and just seeing what happens. I like having fun with it, running features on artists that have been overlooked, making it feel as if you’re signing away your soul to a mythic entity. I think it also comes from me contemplating where my career would be without some layer of music journalism, and how we need curatorial platforms to wade through the hundreds of thousands uploaded to streaming every day.

Not too long ago mainstream culture was not considered cool, and things that leaned into a DIY spirit were perceived as more authentic. Although, in retrospect, many of the quintessential “indie” bands were signed to major music labels. Do you think there’s pop nostalgia because nowadays it is harder to achieve such widespread mass status?

I think that’s a core question that hasn’t been untangled by our culture yet. There’s a lack of mainstream in the way that a lot of us grew up with TV or music releases. That moment where everyone is talking about a thing that happened on that show that everyone has seen, or that artist you can’t escape. The Internet splintered it off into many corners and it’s less of a plateau. That’s why it feels even more monumental when there is a mainstream moment. The Brat release and response has been pretty shocking. A year ago people were quite cynical saying “Pop is over,” and then already this year with Charli, Chappell Roan and Sabrina Carpenter, it’s like “Oh wait, is pop back?” then you have other big artists whose campaigns feel a lot smaller or less mainstream than their previous ones. Overall there’s more ‘poptimism’ I would say, less of those lines of “Oh this is my sincere guitar music unlike this insincere boom-clap music.” At the same time a lot more listeners understand major labels and technology. I’m very curious about where it’s going to lead us. I keep saying this, but I think it’s true that there’s going to be a divide with very functional music on one side, led by AI interfaces and streaming software designed to serve the listener, and on the other, much more theatrical music that feels like cinema, or opera, that has to be witnessed live or experienced. That’s going to become a solution to the mainstream, this sort of directly serviced feedback loop, and this other thing that is constantly trying to shock you.

Words and photos by Fabiola Talavera