At the 58th Venice Biennale, Iris Kensmil is presenting her work at the Dutch Pavilion alongside Remy Jungerman

in an exhibition titled The Measurement of Presence. Atop a modernist mural inspired by the work of artists like Mondrian

and Malevich, Kensmil offers a counterpart in her eight portraits of black women who sought a new utopia. While the flat background of the mural highlights the one-sidedness of predominantly white and male perspectives, the overlaid portraits add physical and historical depth, drawing attention to the fact that the narratives we are familiar with are missing some crucial perspectives.

Both Kensmil and Jungerman are inspired by conceptual artist Stanley Brouwn’s explorations of presence and absence. In her work, Kensmil confronts her own presence as an artist, looking to show, as Brouwn did, that people can develop and determine their own presence in the world. Nonetheless, Brouwn’s black feminist focus highlights the fact that widespread colonial and racist values meant that the woman in her portraits were relegated to the shadows and became absent from mainstream narratives. Kensmil seeks to show how important these figures and their ideas are in our present modernity.

Can you tell me about your exhibition at the Venice Biennale, The Measurement of Presence?

The exhibition features my work alongside that of Remy Jungerman. We have a shared inspiration; we draw from twentieth-century modernism and the avant-garde—for the Biennale exhibition particularly Mondrian and De Stijl, the Russian avant-garde and Stanley Brouwn—with elements of other traditions and positions. We use our influences to register and define our own presence, reassessing our distance to artists, to history and to other people.

My work is made up of three installations. In two of the installations, I present black feminist thinking about the future with eight portraits over a modernistic mural background. In a third installation I reflect on the position of the artist, protecting his authenticity against institutions, critics and too obvious judgements. My work depicts an inclusive history from a black feminist perspective. I honour black authors, philosophers, activists, musicians and the black counter-movement in general which is an undeniable part of modernity.

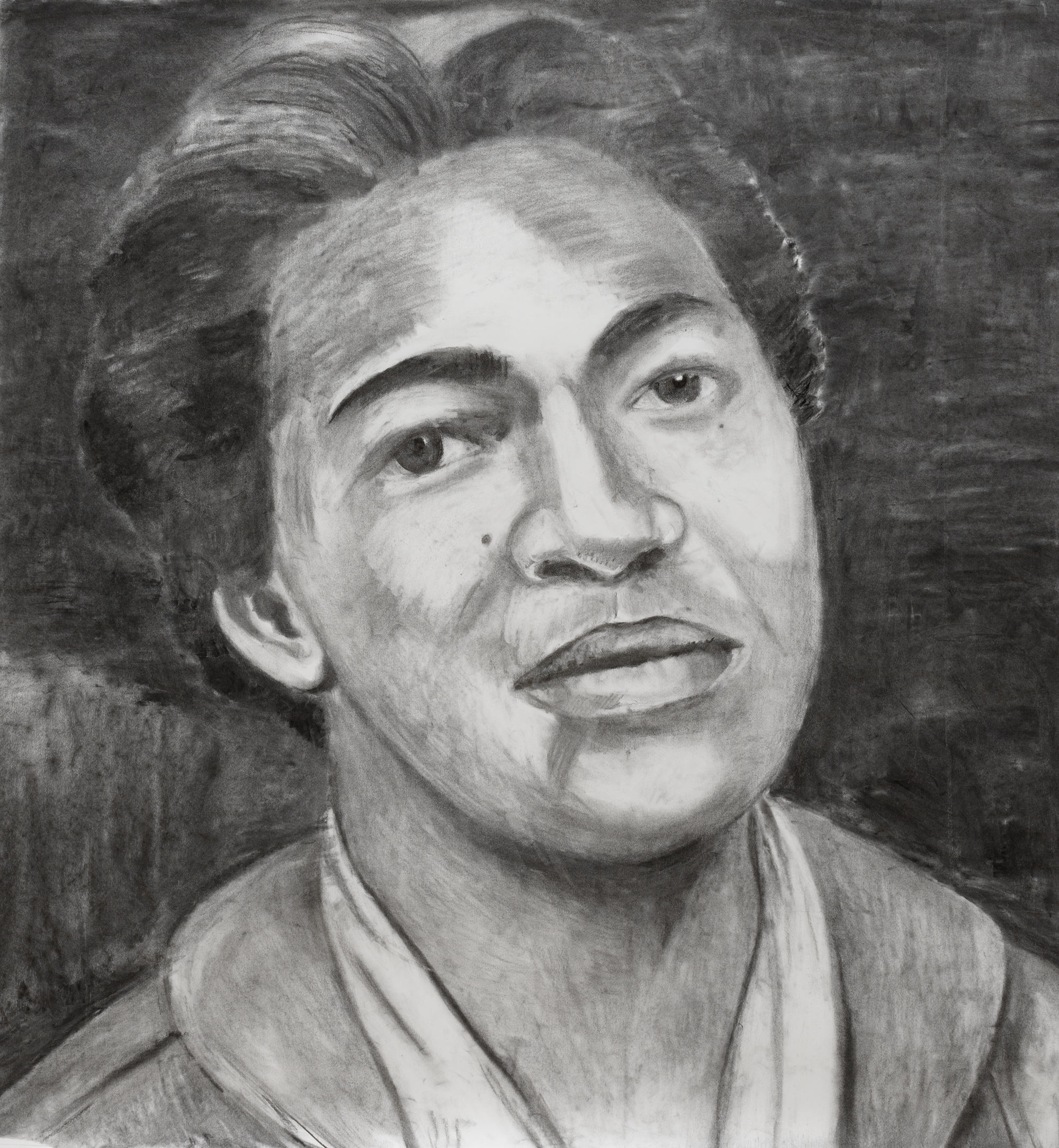

- Left: Study for Black Feminist #1, 2018; Right: The New Utopia Begins Here Claudia Jones, 2018-2019

What is the meaning behind the title of your exhibition?

The title The Measurement of Presence refers particularly to Stanley Brouwn, to whom this exhibition is an homage. His works, which are all about presence in the world and accounting for this presence, inspired the whole concept. I admire Stanley Brouwn for his idealistic confidence that everybody can conceptualize their own position in the world and he is inspirational for his defence of the authenticity of his work. It is essential for the freedom of the artist that he can choose his own strategy for dealing with the reception and framing of his work. Such strategies are a prominent feature of the current discourse, in a striking analogy with other groups such as black feminists. The urge to stand up and claim rights and visibility is a powerful attitude that demands respect.

Who are the people in your portraits?

In collaboration with The Black Archives in Amsterdam, I researched black female utopians, focusing mainly—in view of my own background—on the Caribbean, the US and Europe. From this research I painted seven portraits for my first installation The New Utopia Begins Here #1. These are the iconic black feminists, Bell Hooks (born 1952), the Pan-Africanist Amy Ashwood Garvey (1897–1969), DJ and singer Sister Nancy (born 1962), journalist and activist Claudia Jones (1915–1964), communist and activist for Surinamese independence Hermina Huiswoud (1905–1998), anti-colonial writer and surrealist Suzanne Césaire

(1916–1966), and feminist science-fiction novelist Octavia E Butler (1947–2006).

In a separate wall painting, The New Utopia begins Here #2, I integrate a portrait of writer, poet and activist Audre Lorde (1934–1992) with the mural. I choose Audre Lorde for this piece, because she fought for a way out of the identity-politics, in which society is trapped now. As she says herself in her books: “I am a Black Lesbian Feminist, Warrior Poet, Mother, stronger for all my identities, and I am indivisible.”

What’s the relationship between the background mural and the portraits which overlay it?

The wall painting evokes the modernist utopianism. At the same time, I see the utopianism of that era as a one-sided ideal. The installations correct that one-sidedness by presenting another vision of utopianism espoused by black female intellectuals, women who, in their writing and their actions, expressed their desire to create a better world. The abstract mural is inspired by the work of Piet Mondrian and Kazimir Malevich, whom I regard as the iconographers of modernistic utopianism. But instead of citing them, I compose spatiality and dynamics with elements derived from their work.

Do you think that, by bringing attention to the people who have been historically ignored, art can help to address the problem of their erasure, or is it more about ensuring that they stay part of the narrative going forward?

Ignorance is created by the privileges and prejudices of colonial and racist modernity. Art does not change that history, nor ensure any future, but as an artist, I can try to make works that can’t be ignored and establish a renewed canon for an inclusive future. My portraits are of historical figures who, in the Netherlands at least, have been kept in the shadows. In painting them, I used a white undercoat, inspired by nineteenth-century impressionist painters. This makes the paintings glow with a soft light emanating from beneath the surface. My light undercoat serves to light the figures up, bringing them out of the shadows and underscoring their importance for our present.