Photography is much maligned in the contemporary world; since everything we do, buy, support or say is sustained by photographic images, we’ve also come to suspect them, associating them with the negative emotions they can stir up: envy, guilt and anger. The practice of a photographer itself can be isolating too: detaching and dissociating from what is happening in front of you; not inhabiting the moment but living in parallel. However, a number of practitioners have found potential for something positive in the medium that has long been associated with heightened observation and the attuning of our inner selves to the outer world.

UK-based Tracey Calder runs Mindful Photography courses that promote greater self awareness and alleviate stress among other benefits. “Mindfulness is a word that’s bandied about a lot these days—everyone from Ruby Wax to Oprah seems to be using it—but there can be some confusion as to what the term actually means. Basically, mindfulness means paying attention. It’s a word that can be substituted for any of the following: awareness, observation or curiosity. It has roots in Buddhism, but you don’t need any religious beliefs to practice or benefit from it.” Calder explains.

“People often suggest that mindfulness (and meditation) are ways to empty your mind, but that’s not strictly true. You are not trying to push thoughts, feelings and emotions away, but recognise them, remain impartial, and then let them go. It can help to think of thoughts as cars racing down a motorway (a common analogy). When you become attached to a thought it’s like chasing a car down the motorway and ending up in the middle of the traffic. When you sit by the road and simply observe the cars going by you remain calm and centred. The key is to become an impartial observer, and welcome all thoughts and feelings equally. Crucially, don’t try to empty your mind or relax.”

Calder draws a link between this practice of mindfulness and the practice of photography as a way to allow observations, as well as judgements, come and go; to start to look at whatever is front of the lens as unique, and wrest it from the labels that impede us from really seeing and experiencing the world clearly.

“Photography is a dream vessel. It’s a medium where I collide my thoughts and ambitions with my fears and anxieties”

“As a person who’s often suspicious of the reality and relationships in my life, I don’t trust verbal words”, says the photographic artist Leonard Suryajaya. Suryajaya has spoken openly about his struggles growing up queer in a rigidly patriarchal and religious family in Indonesia; he eventually left for the US, where he met his husband and began to process the trauma of his childhood. Eventually, he began to return to his home country to take pictures, many of them involving his family and his husband. His multilayered, dazzling, trompe l’oeil scenes are both humorous and symbolic, and restage Suryajaya’s past on his own terms—and thereby take control of them.

“Photography is a dream vessel. It’s a medium where I collide my thoughts, ambitions, aspirations and excellence with my fears, anxieties and shortcomings,” he reflects. “To make a photograph is to make physical these dreams and nightmares that occupy me. It’s a way for me to process overwhelming information and uncertainties and transform them into something hospitable and beautiful.”

If painting is the medium of freedom, then photography is the medium of control. In the hands of anyone who finds the world chaotic and disordered, the camera can help reclaim our existence and affirm our authority over our surroundings. “Verbal language seems inadequate and insufficient in communicating the complexities of my humanity.” Suryajaya reflects. “Photography is therapeutic for it ennobles me. It helps me clear out the illusions and discrepancies that envelop me, allowing me to see my worth and realise my power. I’m no superhero, nor can I do telepathy. But being able to communicate multiple perspectives in one instance sure does make me, an alien in America, feel like I’m extraterrestrial.”

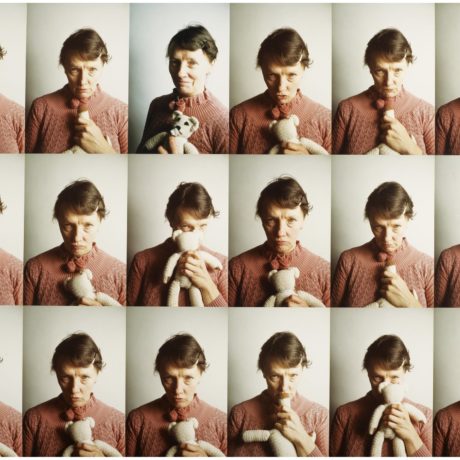

- Left: Jo Spence, Anger Work, 1988. Courtesy the artist

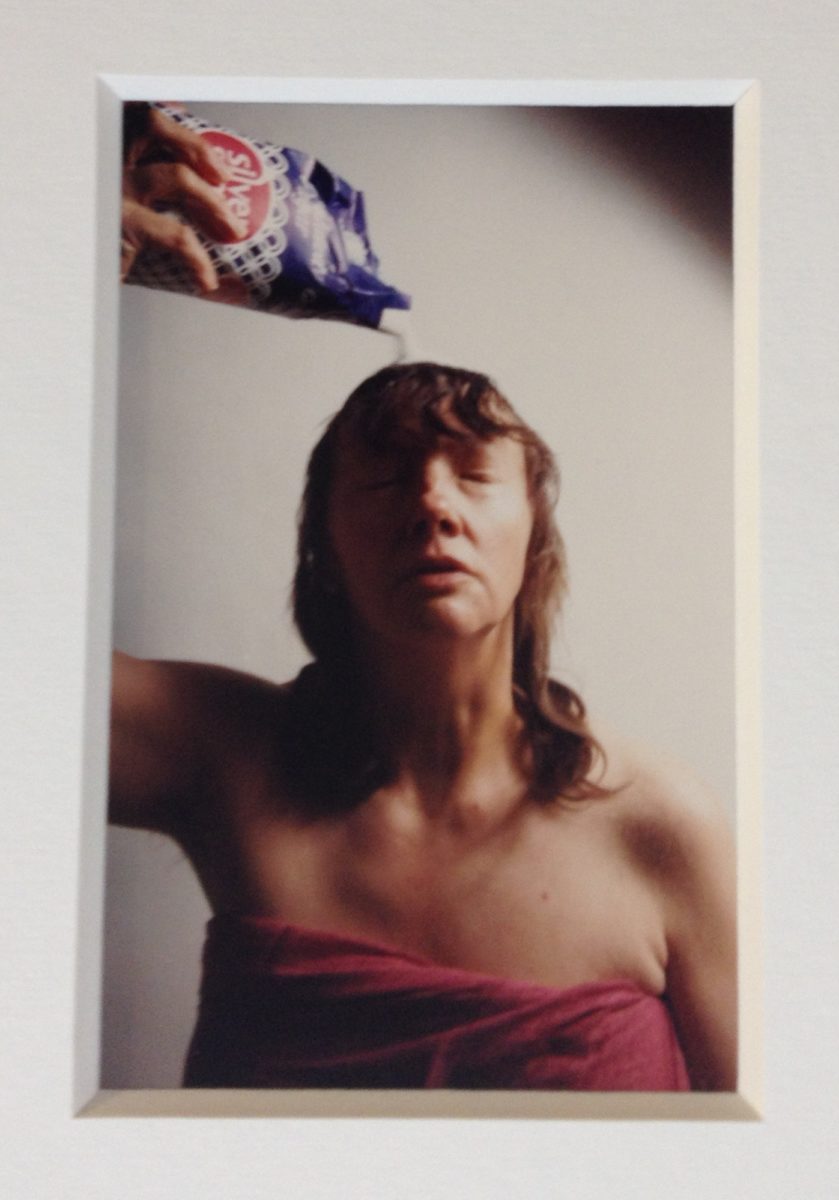

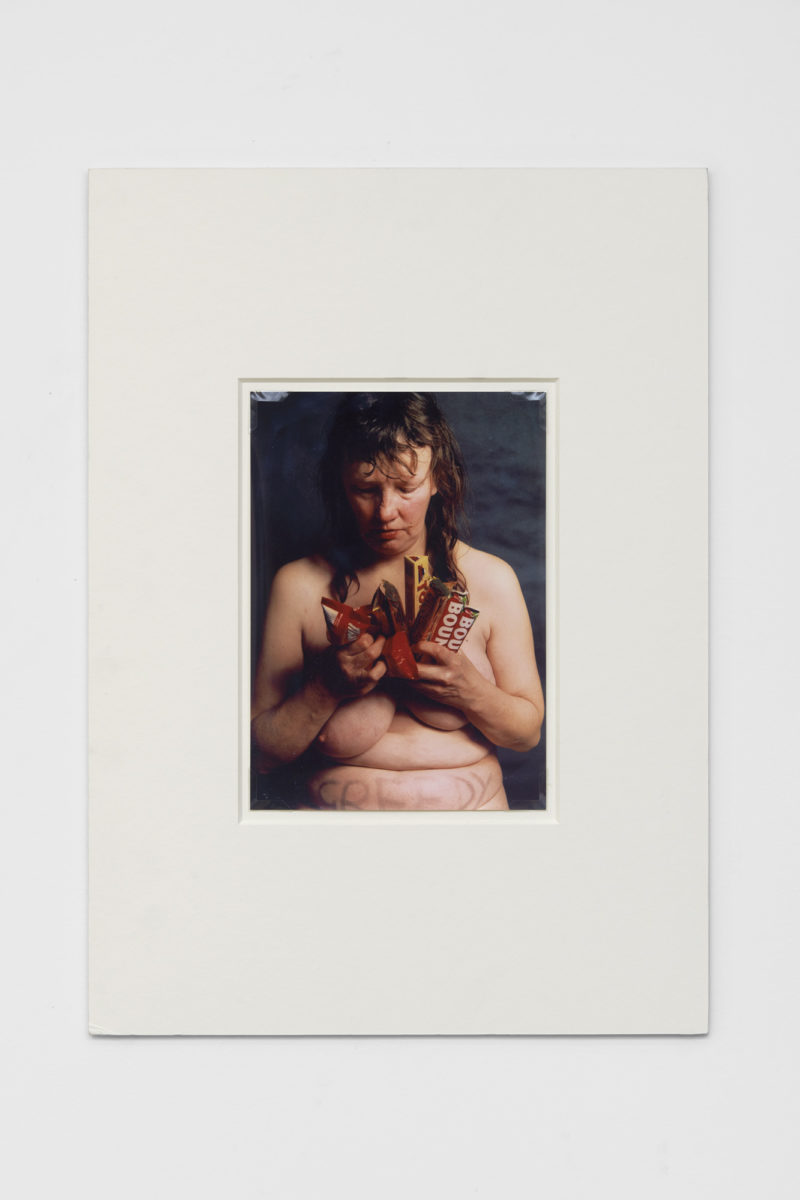

- Right: Mother and Daughter Shame Work: Crossing Class Boundaries, 1988.

Susan Sontag pointed out that the camera is a way of coping with the unfamiliar and the unknown, one of the reasons tourists have been so attached to taking pictures of foreign places. It is why many photographers have roamed outside of their own communities to explore the places they can’t normally see, but might fear; of course, this has often produced negative results, but the photographic act itself still seems to be a process that permits confrontation and catharsis.

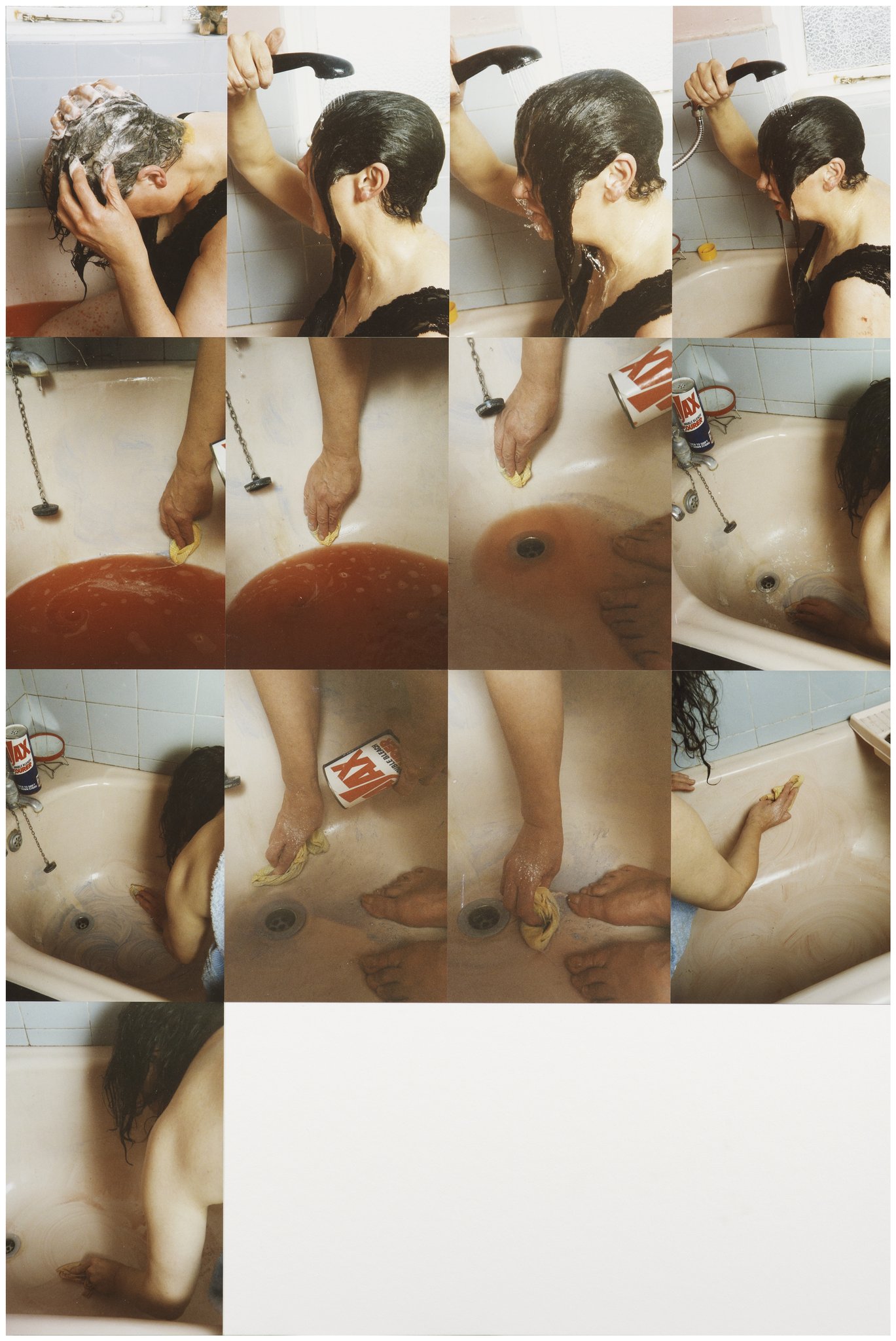

The late Jo Spence’s radical, personal proposition for Photo Therapy remains a pioneering form of photography as a form of healing. Originally developed in 1983 with Rosy Martin as re-enactment phototherapy, broadly the idea was that photographic practice could be used in a therapeutic way—by literally reconstructing your own image, rebuilding yourself in effect from the out in.

“Verbal language seems inadequate and insufficient in communicating the complexities of my humanity”

In a current exhibition on Spence’s photo therapy pictures, made collaboratively in the 1980s, we see Spence dress in masks and posing with props: she addresses her complex sexuality, her desire to be loved by her mother, her issues with anger, her illness, society’s beauty standards and infantilisation. In a 1988 collaboration with Martin, Spence poses as a mother in three images, dressed in the same clothes, serving a plate of food. The maternal gesture is mirrored in all three images but the facial expressions shift from servile to repulsed.

Spence said that she only began to understand her mother through the photo therapy work: “The practice of asking, listening, looking and interpreting fed into my photography for the general public… it was only years later when I was in therapy and trying to ‘speak’ to various parts of myself that I began to make connections with this earlier practice and seek a way of portraying psychic images of myself.”

Spence and Martin’s reenactment photo therapy was prescient, recognising that photography can in fact become the cause of anxieties and illness itself. “Since the introduction of camera phones, many people use photography to regularly document their lives. The selfie has become endemic, particularly amongst young people”, Martin explains, in an email. “But the demands of Instagram, chasing ‘likes’ and curating the perfect life have become dominant. This chasing of the ‘impossible ideal’ was one aspect that Jo and I were challenging with re-enactment phototherapy: this work contests the idea of any possible idealised image of the self, since that is an impossibility anyway. Rather, it embraces and attempts to make visible the multiplicity of identities that any individual inhabits throughout their lives.”

The method they devised is “about exploring aspects of one’s own history within the containment and support of the therapeutic gaze, which offers a kind of mirroring that acts as a witness to the story which unfolds, gives permission and is not judgemental.” Martin’s own works have addressed body image, class, grief and family relationships. The process moves from subjectivities—mapping out the various gazes we experience and how they have implanted external images in us—to embodiment, where the patient can let go and claim their own narrative; the pictures are then used in counselling sessions. “The transformative aspect is needed to offer the ability to create images of the potential for change; finding, for example, an inner nurturing part of the self to challenge a punishing super ego.”

Re-enactment photo therapy “is a collaborative process”, Martin adds. “It is a performative practice; not about capturing an image but seeking to make it happen, to take place. This work is playful. There are parallels to the ways in which children use fantasy play to re-enact scary, troubling scenarios, or to try out different roles, gathering dressing-up clothes and a variety of objects as props, to give form to their desires and fears. The links between play in the child and creativity/play in the adult as theorised by Winnicott have resonance with this practice.”

“It embraces and attempts to make visible the multiplicity of identities that any individual inhabits throughout their lives”

Artist Cristina Nunez has followed up on the ideas of Spence and Martin with her own particular method, which she refers to as the “self-portrait experience”, using self portraiture as an act of self belief and exploration of the inner psyche. While, as Martin points out, this method differs from her own re-enactment phototherapy, it still suggests photography can be used as a form of healing. Nunez has taught her method all over the world for almost two decades, including in prisons and to the terminally ill, inviting all her patient-participants to create self-portraits in her studio that encourage tapping into a ‘higher self’, to release us from the weight of our often repressed emotions.

Many artists of different generations have suggested that photography has saved them—from Nan Goldin and Ming Smith, to Zanele Muholi or Arielle Bobb Willis—the camera pulling them through dark periods of depression or addiction, finding purpose in a world that can be overwhelming or hostile. It might sound straightforward, but like all forms of therapy, photo therapies entail hard work and commitment—the kind of effort and dedication that’s needed to perceive the world differently. Photography might not only be about looking out at the world, but an effective way of looking in at ourselves.