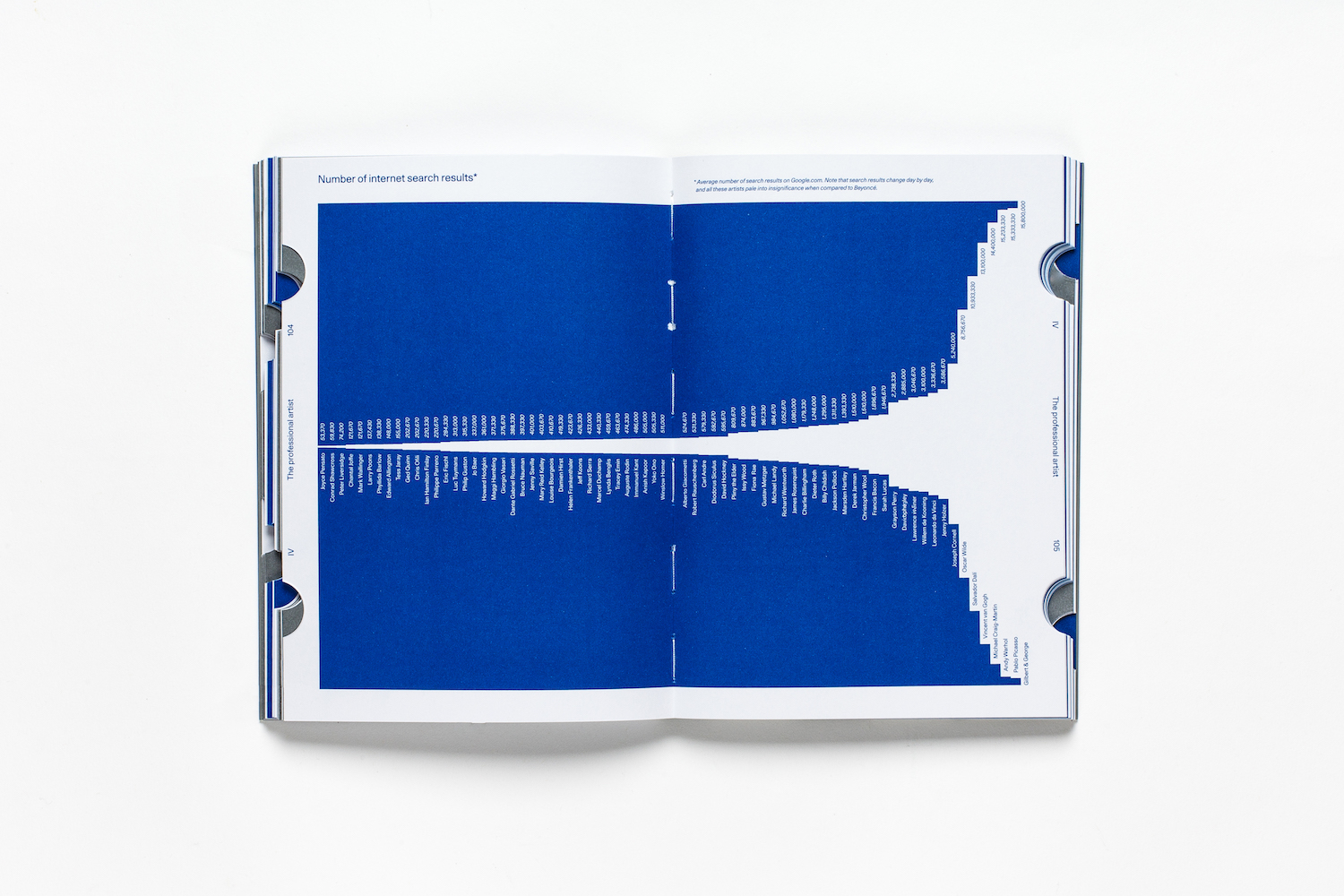

Why do we care what artists say? Their statements are everywhere—in public conversations, magazine interviews, documentaries and Reith Lectures. Some voices, of course, are more prominent than others—the media artist is a familiar type. But amid the sea of quotes and Q&As, we rarely stop to wonder why artists’ utterances matter in the first place.

“Never believe what artists say, only what they do,” David Hockney once quipped. We may wonder, of course, whether he expected to be believed even in this. But beneath his words is an old assumption—a feeling that whatever of value the artist has to communicate is expressed through his or her work. Interpretation, it has been said, is the job of the “professional”—the critic, curator or art historian. Why then pay serious attention to the words of artists—so often wayward, ironic, riddling and subjective?

Ways of Being celebrates the artist’s voice for precisely these qualities. In the book, I bring together statements by some eighty artists—many from new interviews—to highlight the originality and unorthodoxy of their stories and statements. Assembled into a long, meandering sequence of fragments, their voices are akin to real life—unpredictable, contradictory, containing multitudes. They are an antidote to the standardized language of the critic or curator.

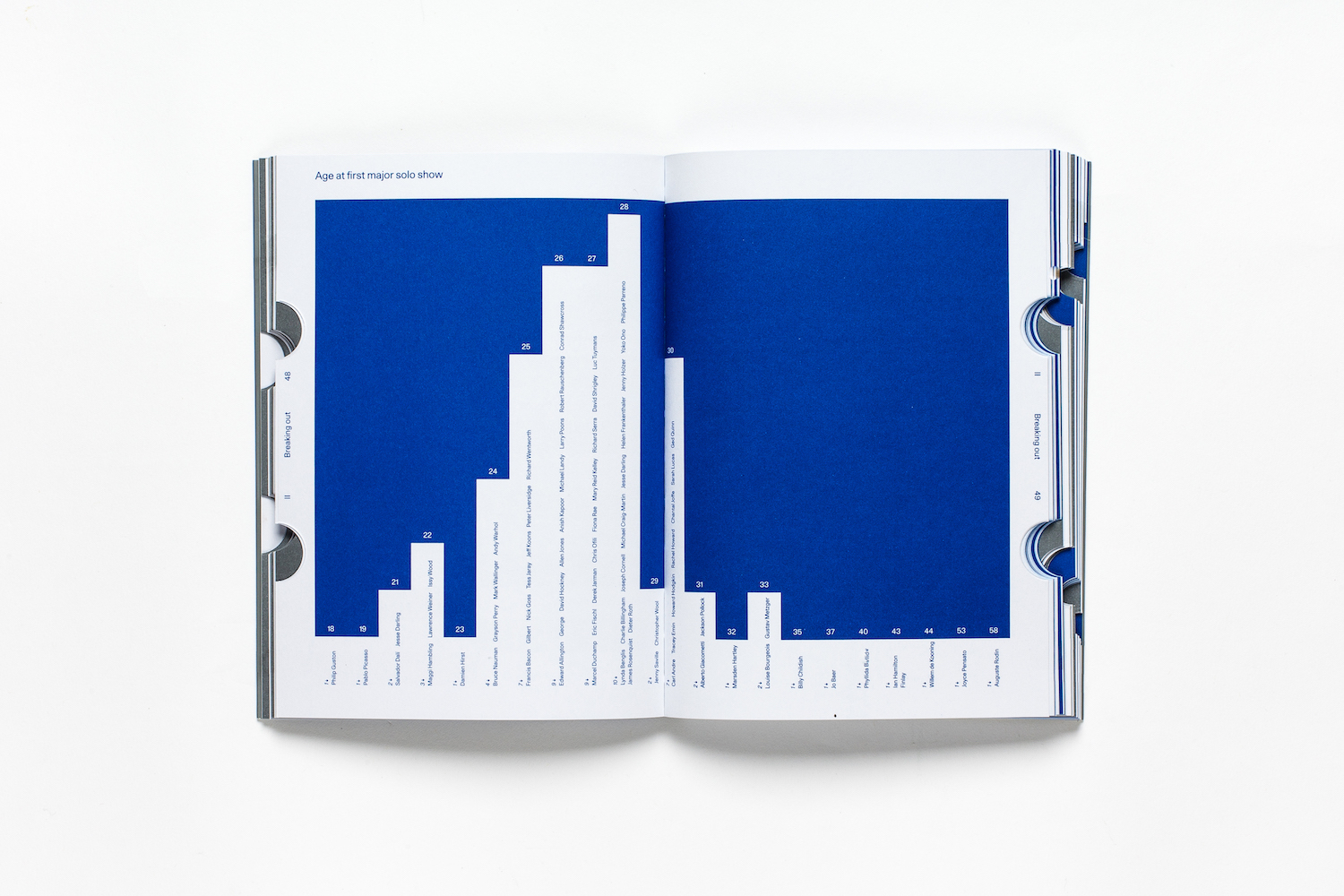

It is perhaps fitting, then, that the book addresses the subject of life itself. What does it mean to be an artist, to create and destroy, succeed and fail? Should the artist be a social being or an outsider? How does an artist get started, and at what point does making art becoming a career? The answers are manifold: there is no single route to becoming (or, for that matter, remaining) an artist—and no agreed definition of what an artist even is. Some reject the label entirely: the legendary American painter Larry Poons claims: “I wasn’t an artist when I was young. I don’t even know if I’m an artist now.”

“What does it mean to be an artist, to create and destroy, succeed and fail?”

Along the way, there is much practical advice for the aspiring artist—as leading practitioners explain how they started and then sustained their careers (“Never get a day job that interests you too much,” for example, or “I would never ‘pitch’ to an art critic or journalist”). More than that, there are insights into subjects such as inspiration, influence, collaboration, isolation and mortality. All help to reveal the conditions in which art is made, and to answer the question of what art is.

When we come to debate the significance of artists’ words, the problem is that we often try to hold up those words as evidence of intention, against which to evaluate the works themselves. In fact, the statements of artists rarely constitute explicit statements of intention. They can often appear tendentious or opaque. Despite this, artists are closer to their works, by necessity, than critics, academics or other viewers. While their remarks are not integral to their works, their words may still be seen to extend, frame, or inflect the works’ meanings. Their words may be analysed in the same way as we analyse their works—as “open texts”.

“In the end, art is not made in academic or curatorial boxes”

Take Robert Rauschenberg, an artist whose tone was consistently, almost evasively, wry. The artist once recounted how a respectable middle-aged woman had come up to him at the Jewish Museum in 1963 and asked why he was “interested only in ugly things”:

“To her, all my decisions seemed absolutely arbitrary—as though I could just as well have selected anything at all—and therefore there was no meaning, and that made it ugly. So I told her that if I were to describe the way she was dressed, it might sound very much like she’d been saying. For instance, she had feathers on her head. And she had this enamel brooch with a picture of The Blue Boy on it pinned to her breast. And around her neck she had on what she would call mink but what could also be described as the skin of a dead animal. Well, at first she was a little offended by this, I think, but later she came back and said she was beginning to understand.”

Rauschenberg’s droll response to the baffled woman might initially have seemed like deflection. But there is something compelling about the comparison between his own material juxtapositions and the woman’s meticulous attire. Without explaining his work in any definitive sense, his response conveyed something of the strangeness of all compositional decisions, whether artistic or sartorial—the way in which those decisions hover (perhaps always) between logic and irrationality. The woman was suddenly implicated within the work, in a way that recalls one of Rauschenberg’s most famous and enigmatic statements: “Painting relates to both art and life. Neither can be made. (I try to act in the gap between the two).”

Often, the epithet of “tastemaker” clings, unchallenged, to the professional curator. Occupying the gap between art and life, this book affirms the role of the artist in determining taste (or deciding what taste even is), what success looks like, why failure has its rewards, and why art matters. Like the woman in mink at the Jewish Museum, we should embrace artists’ words in the hope that we go away, like her, with transformative insights rather than neat exegeses. In the end, art is not made in academic or curatorial boxes. The life and mind of the artist—from which the work emerges—can only truly be expressed in the artist’s own words.