The “culture war” has given us painfully simplified versions of what other people think. But instead of just accusing each other of supporting hideous violence or telling monstrous lies we should ask an equally simple question: Where did our ideas come from? Revisiting the work of Jean Genet and Angela Davis tells us a lot about what we’re talking about when we talk about social justice, especially the links between Black activism and Palestinian solidarity. Two films about these figures tell us a story about how we came to this point.

We sure live in sad times. The global literacy rate for over-15s is 86.3 percent, but we can’t be sure that anyone really reads all that much. We have instant access to all the information that has ever existed, but we’ve ended up with nobody trusting anything they’re told. And the kids are very much not alright—if the tabloids are to be believed, they all sit in class watching ultra-high-definition, ultraviolent, ultra-unctuous, woke anime tentacle torture porn uploaded to grisly Russian OnlyFans leak sites by extremist illegal immigrants on benefits when they should jolly well be paying attention to their fronted adverbials. These times aren’t even that interesting. But it comes as no surprise that an art exhibition would echo the horrible things going on in the so-called ‘real’ world outside.

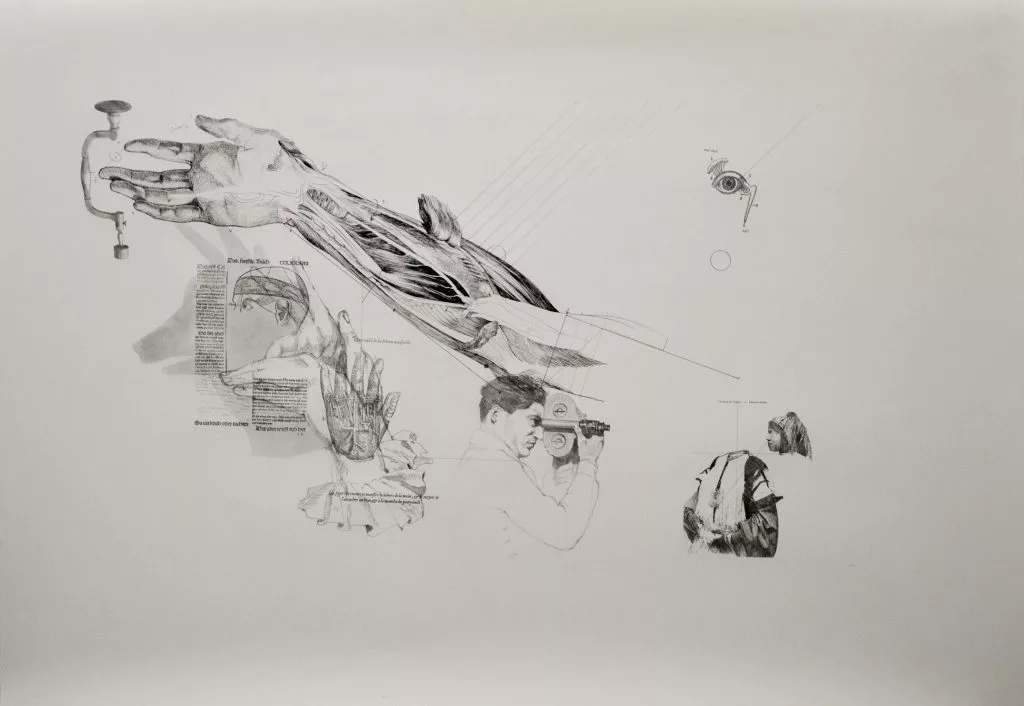

A Convening of Civic Poets at KADIST’s Paris space showed thirteen artists’ work, including films, playlists and conversations, drawings, and other practices responding to social justice issues. These included: the migrant and workers’ movement in the Paris suburbs (Hajer Ben Boubaker); how to use language to criticise dictatorships (Cecilia Vicuña); stigmatisation of queer identities during the AIDS crisis (David Wojnarowicz and Marion Scemama); black civil rights protestors (Helina Metaferia); and dissident Iranian intellectuals murdered by the regime (Jinoos Taghizadeh).

Other events are available, of course. These works were always going to be overshadowed by current affairs. ‘A Convening of Civic Poets’ opened on 6th October 2023: the day before Hamas’s murderous incursion into southern Israel. I saw it two weeks later, during an ashen-skied, windy-wet, wretchedly glitzy Art Basel Paris Plus Week—by this point, the Israeli air force was bombing Gaza City but the ground invasion wasn’t for another week and a half, though there were limited raids and skirmishes inside the Strip that week. Protests, open letters, and calls for boycotts of anyone allegedly representing a ‘side’ followed. The outcome was the kind of atmosphere—vibes so extremely bad as to make your bone marrow shake and turn to that mush you get when you don’t clean a blender properly after making a supposedly healthy very berry-full, thoroughly protein-y, oat spirulina smoothie, put it back in the drawer, and then it stinks up the joint like some tell-tale-hearted carcass straight out of a poorly-engineered true crime podcast—that made it hard to say much without getting cancelled by one irate party or another.

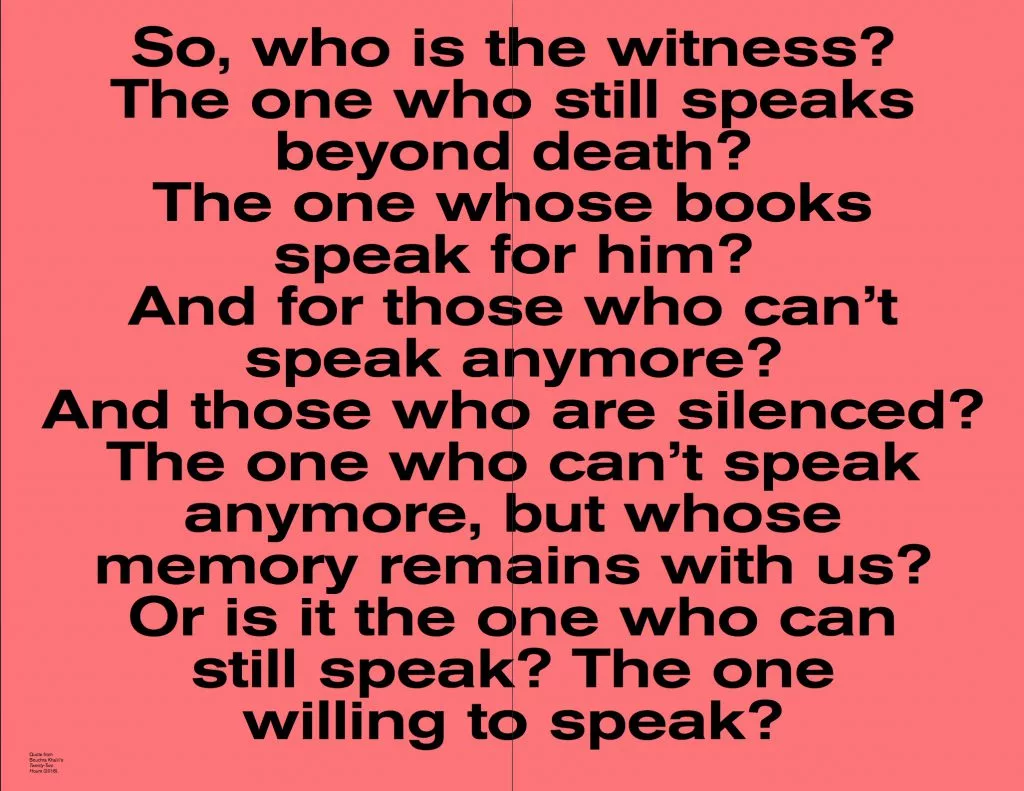

Two works in the show—both documentary films—thus deserve special attention. One is Bouchra Khalili’s Twenty-Two Hours (2018), about legendary French writer Jean Genet’s involvement with radical politics. The other is Manthia Diawara’s Angela Davis: A World of Greater Freedom (2023), about the titular theorist and activist. Even if focusing on them comes at the expense of other works, Genet and Davis have contributed so much to the discourse around the very social justice issues those other works are about, especially Palestinian solidarity, that this becomes almost unavoidable.

The films don’t, however, say anything specific about Palestine: not the land, the peoples who lay claim to it, or the flesh of the fallen thousands fertilising its supposedly holy soil. And even if they’re not even the most influential figures in Palestine-talk in the West, Genet and Davis are vital for understanding it. One obvious way in which they have influenced, is by helping to create a conceptual framework for interpreting Palestinian suffering through the prism of American racism and other forms of social injustice.

Twenty-Two Hours is about Genet’s (illegal) 1970 visit to American college campuses at the invitation of the Black Panther Party. He spent time in Palestinian refugee camps in Jordan soon after, as described in his book Prisoner of Love (1986), though Khalili doesn’t explore this all that much. A World of Greater Freedom, meanwhile, is an extended interview with Angela Davis, in which she discusses the nature and development of her thought and politics since the 1960s. This shares themes that were important to Genet, especially prisons, racism, and the plight of the Palestinian people—and the two exchanged letters, including when Davis was (wrongly) imprisoned for a conspiracy to murder Superior Court judge Harold Haley a few months after Genet’s trip.

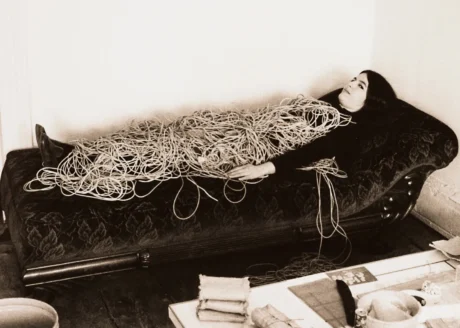

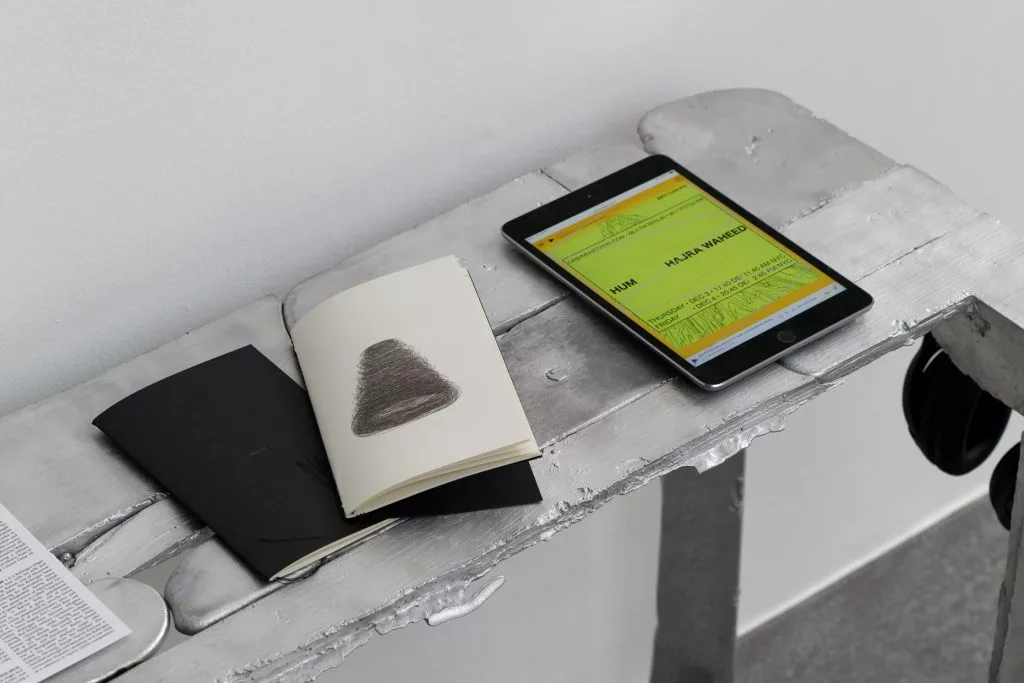

Twenty-Two Hours is in three parts. Part one, ‘The Poet’, deals with Genet’s wretched early life, illustrated by photos displayed on a tablet device captured on camera. Abandoned by his mother, who worked as a prostitute, he was taken into foster care, lived in a penal colony, worked as an apprentice typographer, and deserted the French colonial army, before becoming a thief, a prostitute himself, a prisoner, a celebrated poet, and a ‘comrade of the revolted’. Next, ‘The Revolutionary’, tells the story of Genet’s trip to America. Khalili uses clips of Genet speaking in front of large audiences about the ‘poetic’ core of revolutionary action, armed resistance, and cross-racial alliances, alongside members of the Black Panthers. This is complemented by shots of former Boston Black Panther Party captain Doug Miranda—once a firebrand, now older, greyer, bearded, shot in moody half-light—describing attempts to mobilise students at Yale in the late 1960s. And Miranda appears again in the final part, ‘The Witness’, describing life in the Black Panthers and how ‘super exploitation’ has continued since they were dissolved, leaving intact what he, and many others, see as the relationship between capitalism and white supremacy.

Unlike Twenty-Two Hours, there’s no narrative in the more freeform A World of Greater Freedom. Instead, we see Davis directly and joyfully addressing the camera in her own home, peppered with archival clips from her youth as an activist. She discusses her thoughts and work from her time in prison to the godmother of today’s intersectional thought and activism. Over 77 minutes, Davis revisits these themes, including the interrelationship between slavery, the prison-industrial complex (she didn’t coin the term, but is so closely associated with it that by this point it’s almost her own), police brutality, racism, LGBTQ rights, and global struggles for justice. And it’s scored by a soundtrack that includes the music of John Coltrane (we hear ‘Psalm’ and ‘Wise One’), bluegrass, Arvo Pärt, and archival footage of Nina Simone playing ‘Mississippi Goddamn’ and Billie Holiday hauntingly singing ‘Strange Fruit’.

Genet and Davis give us vital insights into what radical politics—especially in its specifically, and perhaps narrowly, American-branded version—has looked and felt and sounded like since the 1970s. Even if the films don’t provide that many details about the radical wings of new social movements (anti-globalization, environmental, feminist, transgender, or anti-racist activism; the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the Black Panthers, the Communist Party USA, Occupy, Black Lives Matter, or Palestine solidarity) we do learn something about their political lexicon and emotional tenor. Indeed, much of what Genet and Davis say, and similar expressions, can be heard today, repeated in renewed form—almost unchanged, though sometimes frustratingly inexact—in activists’ meetings, academic discussions, at protests, and everywhere online, by the young and idealistic and angry.

If, however, we’re going to make sense of these ideas and expressions and where they come from, we need to cut through the confusions of the ‘culture war.’ That means being sceptical about picking a ‘side’ to channel our outrage or do our thinking for us. And that means doing the hard but sometimes rewarding work required of responsible democratic citizens: giving a fair but critical analysis of ideas in the public sphere by responding to what their exponents have really said. In the case of Genet and Davis, that means listening to what they say in these films in the light of their political writings.

Their books are, luckily, widely available. Twenty-Two Hours quotes directly from Genet’s ‘May Day Speech’, Prisoner of Love, his interview with journalist Michèle Manceaux, and his exchange of letters with imprisoned Black Panther George Jackson, all of which appear in the collection The Declared Enemy: Texts and Interviews (2004). Meanwhile, Davis’s An Autobiography (1974/88), Women, Race & Class (1981), Freedom is a Constant Struggle (2016), have all been republished by Penguin the last five years, with Abolition: Politics. Practices. Promises, Vol.1 (2024) as a recent addition. Anyone seeing the films can then link what they see and hear with what they can read, connecting today’s anti-racist and pro-Palestinian slogans with those of the past. All we have to do is quote them; textual scholarship is unnecessary. The result is two important, interrelated areas to explore: exciting rhetoric about revolution and how to achieve it, and the unglamorous hard work of grassroots activism.

On the one hand, Genet and Davis both emphasise what we might call the ‘aesthetic’ dimension of protest, especially the importance of poetry and music for revolutionary politics. The problem is, however, that they both occasionally take—or, at the very least, invoke—a romantic attitude towards violence. This cannot but evade the horror of taking someone else’s life for a cause you believe to be just. On the other hand, both stress something that was still quite profound in 1960s and early-1970s America but is now an obvious and basic fact about democratic politics: what it takes to build multiethnic coalitions to challenge and undo racial injustice. The problem with this comes down to left-wing factionalism, and how intersectional thought is criticised by those who still accent traditional forms of class politics.

Genet emphasises the lyrical qualities of revolutionary action because, he says, ‘a poetic emotion lies at the origin of revolutionary thought.’ To this end, he links the actions of the Black Panthers to the spirit of the rebelling students of Paris in May 1968, without whom he ‘completely and effortlessly sided,’ resolving that he ‘would not rest’ until that spirit returned, ‘provoking an explosion of joy and liberation.’ Davis’s assessment of this is, however, far more precise and less fanciful than Genet’s. She explains that she’s interested in the ‘epistemological possibilities’ inherent in making art, especially music. She says that the modern age trains each of our senses separately and then makes an absolute distinction between the senses and the intellect, a division that music can help to undo. To explain this, she compares the blues and jazz as two expressions of ‘the dialectic of freedom and unfreedom.’

The blues was produced by the descendants of enslaved people—people who were, technically, formally free but faced deep injustices even since emancipation. In one chapter from Women, Race & Class, Davis explains this in terms of the experiences of sharecroppers and convict labourers. They “bore the familiar stamp of slavery,” as she puts it, even if they weren’t still enslaved. Sharecroppers had to pay extortionate rates of interest on the land they rented and the crops they harvested, even if they, as per Lockean liberal political philosophy, owned their own bodies and labour; convicts, meanwhile, arrested and imprisoned for even minor offences, could be worked to death in a way that wouldn’t have been possible when they were slaves, and thus valued as property that could be bought and sold. Under these conditions, the blues allowed people to freely characterise their own experience of unfreedom.

But, Davis explains, the blues was a formally restrictive genre. It confined musicians to a set of unbreakable parameters (call-and-response patterns, the hexatonic scale, twelve-bar chord progressions, blue notes, grooves formed from shuffles and walking basslines), so that they once again experienced a moment of unfreedom even when they were meant to be free. On Davis’s account, the formal limits of the music itself were fragmented by Bessie Smith, who influenced Billie Holiday, and ended up being redeployed in jazz as an element in the struggle for freedom in two ways. There is, of course, the freedom to improvise—Davis herself doesn’t mention this, but Diawara’s use of Coltrane recordings certainly implies it. The second is because Billie Holiday challenged audience segregation when she played in venues in the South.

This is where revolutionary poetry meets reality. Davis identifies the importance of Nina Simone’s ‘Mississippi Goddam,’ which urges politicians and civil rights leaders that desegregation (in schools, housing, leisure activities, and everyday civil life), mass participation (in democratic processes), and reunification, were all ‘too slow.’ Davis claims that this song became the anthem of those who were dissatisfied with figures like Martin Luther King who preached non-violent civil disobedience, making the movement for racial justice more militant.

This was represented by the Black Panthers, with whom Davis had a complex relationship. Genet, however, saw the Panthers in direct musical terms, suggesting that black political culture had been reborn in music and a revolutionary consciousness that makes black people—unlike the working classes in more conventional far-left politics—the bearers of revolutionary thought and action. This is why Genet openly echoes Black Panthers like Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale when he describes African-Americans as being ‘colonised within a white empire.’ This is, Genet thinks, founded on institutionalised contempt—the rich for the poor, white people for black people—housed, supported, and promoted by the press, religion, charities, trade unions, universities, advertising agencies, and the police. He argues that racial divisions have led to a situation in which different groups live in different versions of America: white people enjoy all the freedoms and benefits of liberal democracy, while black people live under an ‘oppressive fascist regime.’

This is, apparently, what justifies armed resistance against oppressors, according to statements published in Party publication The Black Panther and elsewhere, though Khalili doesn’t use this material. According to The Black Panther’s inaugural editorial (March 23rd 1968), ‘indiscriminate violence’ is not applauded, but ‘the only response to the violence of the ruling class is the revolutionary violence of the people’; armed struggle is, according to another editorial (April 25th 1970), ‘the basic premise for relating to the colonial oppression of Black people in the heartland of Imperialism’. Hence, according to Party founder Huey P. Newton, the justifiability of ‘revolutionary executions’ of individual police officers, who represent and embody the ‘occupying army.’ However, Genet explains that his attraction to the Black Panthers is, in fact, ultimately literary: he says that they hated and wanted to destroy the white world in the same way that he attempted to pervert and corrupt the French language from the inside. One key difference between Genet and Davis, of course, is just how far this rhetoric goes.

Davis is, for one thing, more cautious than Genet. For Genet, revolutionary acts have “a freshness that is like the beginning of the world,” not just a poetic creativity, but one that is almost divine, demiurgic in its capacity to make and remake all that is. For Davis, however, as the title of her book suggests, the work of becoming free, of freeing yourself and others, is an ongoing activity. Freedom is, then, a process and not an ‘object’ that comes about all of a sudden, out of nowhere, one fine day, thus ending all injustice; these very challenges, and the lack of guarantees, are what makes the struggle for freedom so rewarding in the first place. Indeed, as she puts it in one interview from Freedom is a Constant Struggle, the major challenge of our age is less to poetically tear everything up right-here-right-now, than to “infuse a consciousness of the structural character of state violence into […] these spontaneous responses [which] will soon lead to organisations and a continual movement.” This key difference is what defines the second major theme of the films: the pragmatic question of how to act politically at all.

Genet’s politics were, we are told, deeply informed by his own identity. He was a hopeless outcast, rejected and almost destroyed by the system. Hence his willingness to forge bonds with others like him. He didn’t just begin from a position ‘outside’ the system but turned this status into the main—if not the only—position from which revolutionary politics can be done. Davis, likewise, focuses on the struggles of outsiders—slaves, women, prisoners, people of colour—to ‘build a new world.’ The question then becomes how and under what conditions we can think and act together, building a force that makes room for everyone in the name of freedom.

Genet certainly stressed forming tactical revolutionary alliances between black and white groups, modelled in part on the ‘revolutionary necessity’ exhibited by the Third World revolutions of the time. This does, however, require white people to exhibit a ‘delicacy of heart’ in their politics, deliberately erasing their own privileges—especially how they are treated by the police—without arrogantly assuming that they can take authority in the movement. Black people are, nevertheless, right to accuse white people as a whole of the oppression under which they suffer, and it is white peoples’ responsibility to do this to overcome the two main, equally damaging, political options: domination and paternalism.

Davis is less unsparing, emphasising the meaning of ‘universalism,’ both in terms of who the revolutionary subject is and what they are acting for on the basis of the values they have. Because Davis thinks all oppressions are linked, one universalism always implies and incites another. Indeed, she explains in Freedom is a Constant Struggle that the issue isn’t just how race, class, gender, sexuality, nation, and ability are intertwined, but ‘how we move beyond these categories to understand the interrelationships of ideas and processes that seem to be separate and unrelated.’ Hence her emphasis, since the 1980s, on the links between anti-racist and feminist activism, which these days extends to transgender activism.

Thus, in A World of Greater Freedom, she says that this universalism is implied in the very phrase ‘black lives matter.’ She explains that, like feminism, this has methodological implications and—perhaps contradicting dominant interpretations of her positions and influence—doesn’t fix or essentialise identities. Thus, black struggle transcends the narrow category of blackness because others are involved and have contributed in the struggle for black liberation; this blends with, borrows from, and reflects her critique of a ‘bourgeois individualistic’ (i.e. liberal feminist) approach that proposes the supposedly universal concept of ‘women’ that was, in fact, implicitly or explicitly raced as white; similarly, she explains, the current movement for the rights of transgender people offers something far more significant than a broader understanding of gender—it involves challenging ideology, which resides in definitions of what counts as ‘normal’.

While A World of Greater Freedom is less specific than Davis’s own writings—occasionally infuriatingly merely suggestive or just plain imprecise, even when they specify that activism has to focus on concrete issues like housing, education, and jobs—she’s more specific than Genet. Genet speaks in mysterious, even apocalyptic terms when he says that “American civilisation will disappear. It is already dead because it is built on contempt.” Doug Miranda, meanwhile, openly states in the third part of Twenty-Two Hours, that although members of the Black Panthers encouraged each other to read the writings of Frantz Fanon, Albert Memmi, Malcolm X, and Eldridge Cleaver, they had little to no in-depth understanding of politics, the history of revolutions, or how to organise one in the present. Davis, while obviously far more theoretically informed than either Genet or Miranda, states quite rightly that this isn’t a prerequisite for trying to understand and transform the world: while ‘praxis,’ in the radical political sense, is different from mere ‘practice’ because the former is informed by theory, engaging with the world doesn’t necessitate academic preparation, just thought.

No doubt, both Twenty-Two Hours and A World of Greater Freedom will infuriate any viewers who are knee-deep in the slimy stinking guts of the culture war. That’s especially the case for conservatives, whose outrage will be directed at what they (unhelpfully) call a divisive ‘identity politics’ that tries to smuggle harmful ‘woke’ or ‘cultural Marxist’ (an odious and, above all, inaccurate term) propaganda into social institutions where they have no place or the minds of the impressionable young, all hip-hopped up on TikTok and radioactively luminous breakfast cereal replacement energy drinks. The same people will, likewise, repeat Margaret Thatcher’s comments about the Provisional IRA, denying that there is any such thing as ‘political violence,’ only terrorism and ‘criminality’ (a vague term that seems to apply to everything from buying a lil bit of kush to share with the boys, to drunken assaults outside suburban nightclubs committed by beery, lovebitten former boy band members with Astrazeneca facial tattoos and unevenly developed biceps, to global jihad). Of course, radical activists repeating the words of Malcolm X and others, maintaining that liberation can and must be achieved by ‘any means necessary’ without specifying that this might not necessarily let combatants make Instagram accounts where it’s just them wearing children’s ragged scalps around their necks like they’re Connell’s sexy chain in Normal People.

Both groups—and all of us, really—would do well to read and understand Protocol I additional to the Fourth Geneva Convention of 12th August 1949, ratified on June 8th 1977. It would be especially, unconscionably spiffy if we cheerily paid close attention to Article 1(4), which states that: as per article 2 of the original document—in which the convention applies even in cases where a state of war is not recognised by one of the parties engaged in combat and when part or all of a territory is occupied, even if there is no armed resistance—relevant situations also include ‘armed conflicts in which peoples are fighting against colonial domination and alien occupation and against racist régimes in the exercise of their right of self-determination.’ This has to be our starting point if we’re going to clarify statements by Genet, the Black Panthers, and those who adopt the language of colonial oppression and apply it to members and institutions of the state apparatus of liberal democracies, not to mention civilians.

Written by Max L. Feldman