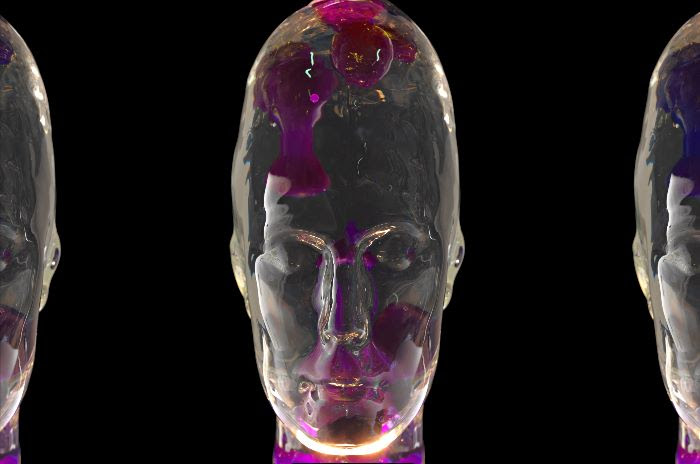

I Magma & I Magma App. Co-commissioned by Serpentine Galleries and Moderna Museet, 2019. Photograph: Prallan Allsten/Moderna Museet

Brace yourself for Jenna Sutela: her work traverses some pretty big ideas. When we meet, our conversation bounces between neuroplasticity, psychedelic histories, altered consciousness, encryption and the I Ching. But, somehow, it all makes sense thanks to the formally simple and beautiful yet technically complex art that she creates to explore these concepts. Sutela’s piece I Magma is a two-part commission in the form of an installation at Moderna Museet in Stockholm, which showcases lava lamps in the shape of the artist’s head, and an app created as part of a Serpentine Galleries series of digital commissions.

“Machine learning is the most ‘living’ intelligent form of computing”

The lava lamps in Stockholm are filmed in realtime, and the camera footage visuals are combined with data from app users’ GPS locations. This forms a number of different shapes, which have been categorized by Sutela and her collaborators (language generation from poet and programmer Allison Parrish, UI and app development by Black Shuck and artist and creative technologist Memo Akten) into around 100 words. This combination of datasets then generates phrases and aphorisms that act like horoscope-esque predictions, which are delivered to each app user daily by push notifications. The fact the data is gathered collaboratively—through lava shapes, location and user numbers—means that with each download of the app the network expands and forms something of a metaphor for the shifting, strange and often unexplainable nature of humanity’s shared but individual (and frequently digital) future.

I Magma is complex, as it has two separate components; one follows a more “traditional” exhibition format, physically presenting work that looks nice, the other is a more nebulous entity as an app. Why was it important to have both?

In my works I’ve often used physical, living materials as a source for computing, such as bacteria slime walls [the artist has previously used a “many-headed” slime mold called Physarum polycephalum]. There’s a sense of randomness to them—that’s why it was always clear I wanted to make a physical part of the installation as well as a digital one.

It also appealed because it was a difficult task. Usually when you create a digital piece of art you want it to be experiential. I find the idea that you have to go to a website every day, for instance, a hard way to approach a task. But the app infiltrates your everyday life just for the three months of the commission with daily push notifications.

Another thing I wanted to be mindful of is that there are so many art websites or digital projects that slowly degrade, so this piece feels alive—but it doesn’t have to live forever, it’s almost like a performance.

How do you see the human form (the heads) and the idea of AI or intelligent computing intersecting?

I often work with living materials, as well as computing and synthetic lifeforms, so the combination always felt natural, as machine learning is the most “living” intelligent form of computing. It’s hard to make sense of how an intelligent machine came to a conclusion or a certain output—it’s like the Black Box Problem.

I’ve been looking at the relationship we have with organic synthetic entities around us, things like the role of gut bacteria in our thinking. Machines work as our interlocutors all the time, even though they’re slightly alien to us, they make us who we are and make everyday life how it is. So in this project I wanted to look at patterns and meanings from the lava in the heads.

“I wanted to look for signs and symbols and meanings in lava shapes instead of just randomness”

Why lava lamps?

I was interested in their place in the history of psychedelic technology and in the history of computing. In the nineties, [computer hardware company] Silicon Graphics used a lava lamp as a random number generator. [The Lavarand, which photographed the patterns made by the floating material in lava lamps, extracted random data from the pictures and used the results to seed an algorithm-based number generator used for things like computer simulations and electronic games.]

In a way, any living material or chemical reaction would be more random than a computer, so my piece aimed to be in line with that Californian ideology that experimented with lava lamps as a source for random numbers. The reason they’re in the shape of my head is that the lamps also act as a symbol for neuroplasticity and altered states of consciousness and turn those ideas around: with the app, I wanted to look for signs and symbols and meanings in lava shapes instead of just randomness.

Sporulating Paragraph, 2017. Courtesy the artist and Momentum 9. Photo by Istvan Virag © Punkt Ø/Momentum 9

I Magma is also said to place an emphasis on altered states of consciousness and “the creation of artificially intelligent ‘deep-dreaming’ computational systems that mimic the brain. Can you tell me more about that?

We were looking at machine intelligence trained with different categories in mind, and used a corpus of various different mystical folkloric sacred texts; so all spiritual practices combined in a single database. One reason for that was stylistic, to get a “mystical” tone, but we needed a lot of text—it’s the more the merrier with machine learning to make it interesting. Then we hand-picked trip reports from Erowid [an online platform for information about psychoactive plants, chemicals and related issues] and notes by Alexander Shulgin [the psychopharmacologist, credited with introducing MDMA to psychologists for psychopharmaceutical use in the seventies]. So it works well with the lava lamps, it gives it an edge.

“We feel we need to make sense of life in one way or another”

The app acts as a divination tool when it looks at the shapes and categorizes them into 100 different words —everything from “snake” to “angel”. We were trying to come up with categories as far from each other as possible. Then the machine generates predictions or aphorisms from these, but it sees things in a way that only a machine would caption images. It starts looking at the text we put in from the spiritual readings and generates each individual phrase, so it might start talking about paradise or just something like an apple.

So where does the idea of the ancient Chinese divination text, the I Ching, come in?

Any of the readings or aphorisms say something about our future: the idea is there’s somehow an element of chance. Even the name of the app is based on the I Ching. Another reference to computing history is that Gottfried Leibniz [inventor of the modern binary number system that formed the basis for binary code in 1689] was inspired by the I Ching.

By exploring alternative forms of intelligence, I Magma draws a line between the histories of mysticism, psychedelia and technology, and a lot of that was influenced by divinatory practices such as the I Ching, but bridging these ancient systems of knowledge with our contemporary attempts to divine the future.

Beyond the references to the history of computing, I was also interested in these slightly alien machines’ presence in our surroundings—like our ongoing search for extra-terrestrial intelligence, for instance. We feel we need to make sense of life in one way or another.

I Magma app by Jenna Sutela

Available to download from i-magma.ai for iOS and Android

Exhibition on show at Moderna Museet, Stockholm, as part of Mud Muses: A Rant about Technology, until 12 January 2020

VISIT WEBSITE