There is something limitless about Jenny Holzer’s Truisms series. These works spring from a pool of around 300 statements of “truth” or cliche (originally conceived between 1977-79, when the US artist was an independent student in her twenties), yet their reach feels genuinely expansive. Holzer’s Truisms snag our attention by taking on familiar, reassuring forms in public spaces; they’re a piquant side to what Holzer describes as “the usual baloney” we ingest through mass media—and it disrupts and haunts us with its glowering suggestion.

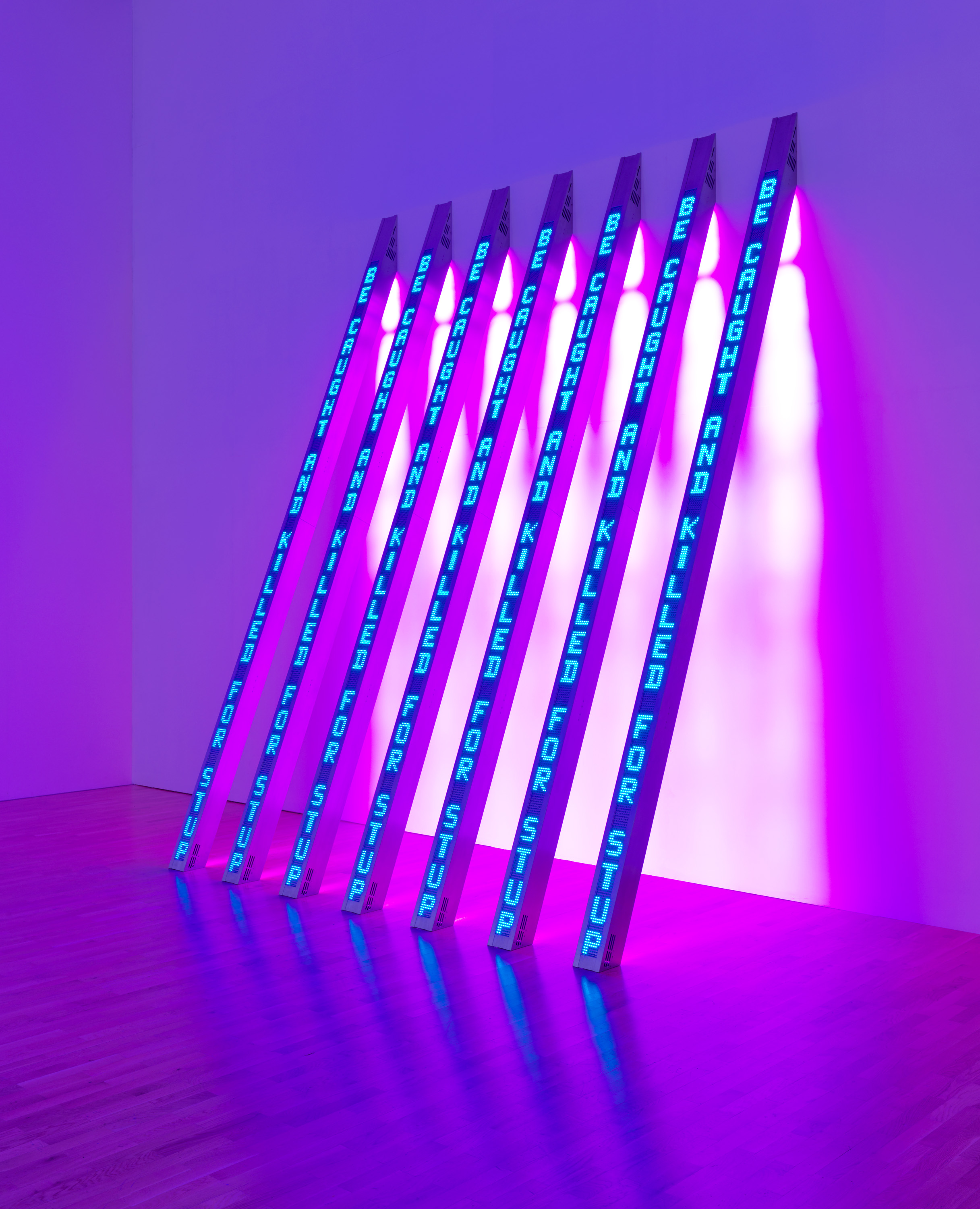

Holzer has printed these snappy maxims on billboard placards, on illuminated displays (including grand landmark settings from early-‘80s Times Square to 21st-century football stadiums), on stickers and T-shirts—in 2016, R&B vocalist/alt-rapper Frank Ocean wore a Truisms tee in the video for his track Nikes, prompting a new rush on its designs. Truisms is arguably in its truest guise, however, as a digital mantra.

“Viewed in the modern day, Truisms reads like an insistent, torrential Twitter feed”

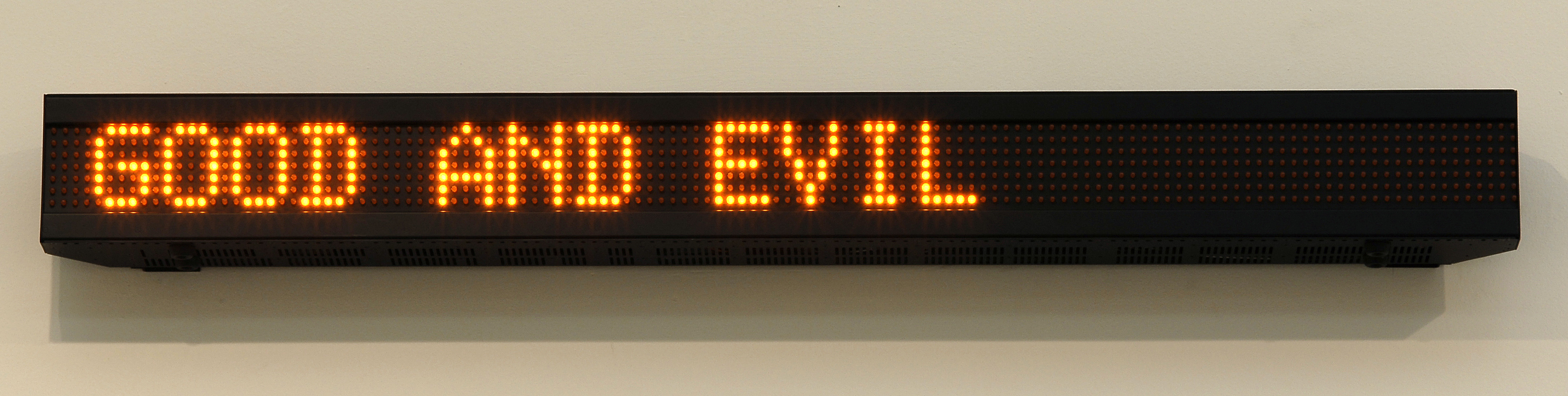

The first time I encountered Truisms was in a compact LED display (dating from 1984)—initially at Dallas Museum of Art, and later tucked by a stairwell in London’s then freshly opened Tate Modern. I’ve always found it alluring and agonising—near-impossible to tear away from its infinitely looping messages. It evokes the “hypodermic needle” model of mass communication, which stems from 1930s media theory, and posits that we’re “injected” with the meanings of messages we receive. We might be passive consumers, but Truisms also triggers a glut of sensations: amusement at its surreal wit; a weird conviction in its emphatic, flashing and dashing amber capital letters (designed to reflect the inflections of speech, but also bringing to mind commercials for shopping bargains, movie programmes, travel warnings); confusion at its blunt contradictions. We might sadly read that CHILDREN ARE THE CRUELEST OF ALL, followed in kinetic sequence by a surge of optimism: CHILDREN ARE THE HOPE OF THE FUTURE.

Truisms 1984 © Jenny Holzer, Tate

“Even the digital brain can only process so much, but Holzer’s bite-sized “truth bombs” remain a subversive pleasure”

While many of Holzer’s other works have employed more directly political/feminist/anti-war missives, Truisms strikes a unique chord. Its original tech might have reached information capacity (the Tate catalogue explains that “The memory of the electronic sign, which has a capacity of approximately 15,000 characters and commands, limited the amount of material that could be included”), but it somehow never feels out-of-touch. Viewed in the modern day, Truisms reads like an insistent, torrential Twitter feed; it is splendidly placed in an era where social media grips mainstream consciousness, even though it predates it by a few decades. At the same time, it keeps scrolling at a spirited pace, never becoming bloated or stagnated like some online message board.

CHANGE IS VALUABLE WHEN THE OPPRESSED BECOME TYRANTS… DON’T PLACE TOO MUCH TRUST IN EXPERTS… PURSUING PLEASURE FOR THE SAKE OF PLEASURE WILL RUIN YOU…

Even the digital brain can only process so much, but Holzer’s bite-sized “truth bombs” remain a subversive pleasure. Truisms gives us these short, sharp, brilliantly warped bursts of “woke”—we are always consuming, we are suspended in a flurry of information; we are, for now, still feeling something real.