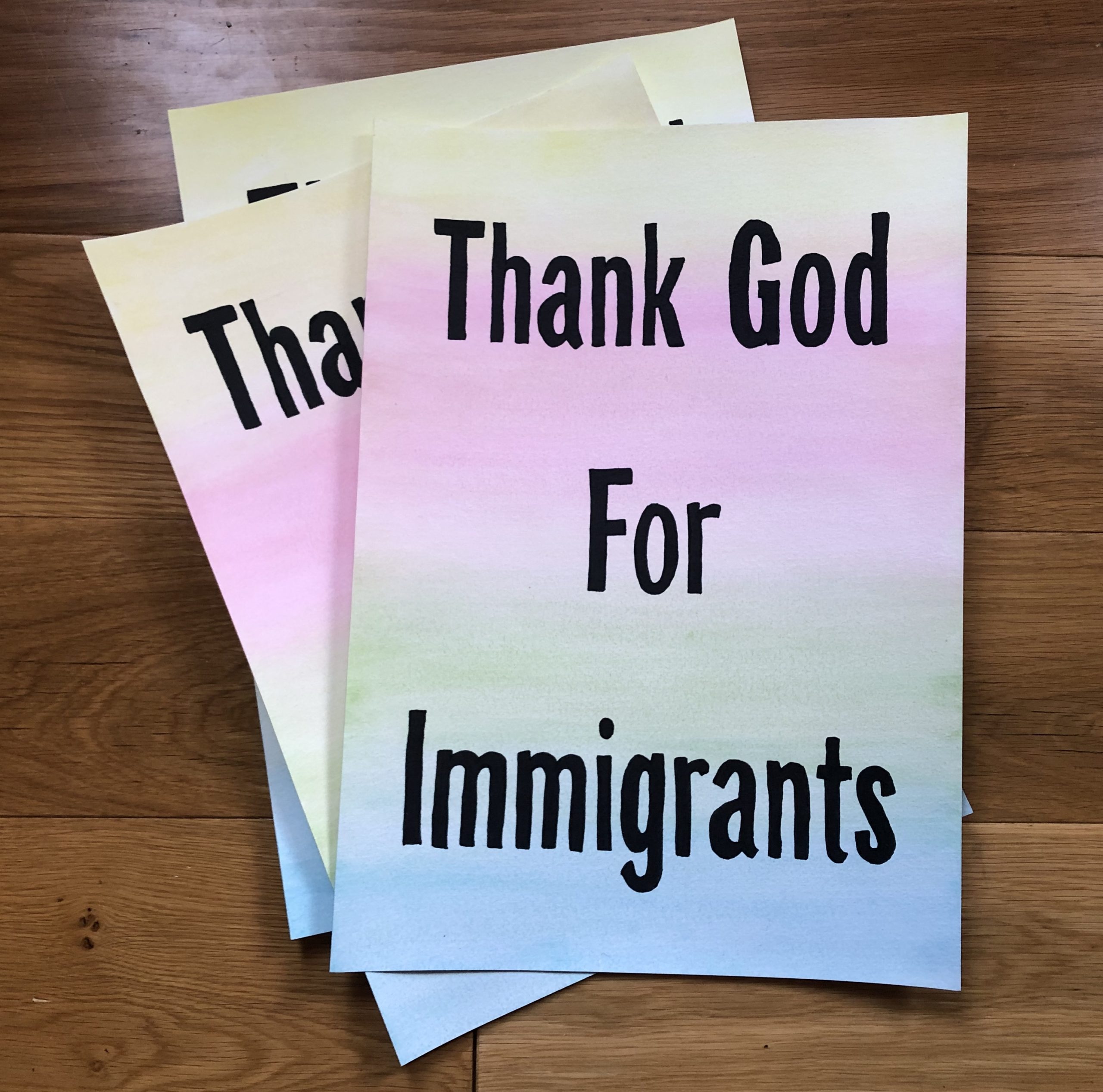

Thank God for Immigrants watercolour posters

When the UK’s coronavirus lockdown led to an outpouring of support for healthcare staff and critical workers, British artist Jeremy Deller sought to capture the spirit of the times. The result was Thank God for Immigrants, a dreamy pastel-rainbow poster produced with Fraser Muggeridge Studio, with proceeds split between two charities: Refugee Action, which supports refugees and asylum seekers, and The Trussel Trust, which supports food banks across the UK.

The first run of 500 sold out within days, with the A2 posters soon appearing in windows and storefronts across London; a further edition of 2000 prints followed. As the lockdown in the UK eased at the end of July, the posters became available to buy at Copenhagen Contemporary—with proceeds going to the Danish Refugee Council. The image has also been projected onto buildings in Barcelona. Watercolour versions of the poster have now gone on display in five London hospitals, as part of a project to deliver new artworks to 100 NHS staff respite rooms, allowing immigrant staff to see work directly.

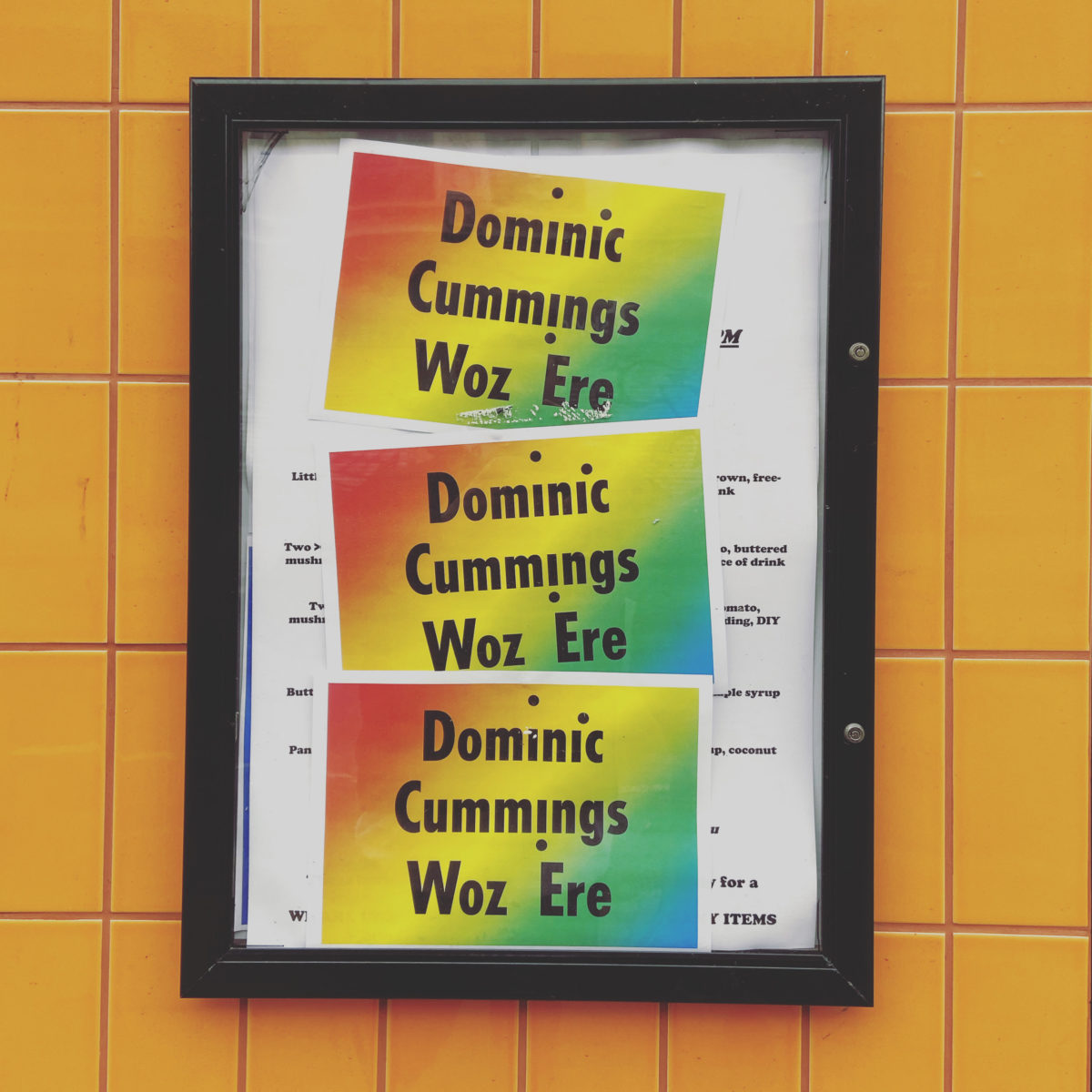

- Left: Fraser Muggeridge Studio and Eleanor Vonne Brown, Dominic Cummings Woz Ere (2020)

- Right: Fraser Muggeridge Studio and Jeremy Deller, Bless This Acid House. (2012)

“With galleries closed, the private sphere of the home became a visual portal for artworks through front windows”

Widely known for his political, public-facing projects, Deller was influenced not only by the revaluation of critical care workers during the lockdown, but also by the changing nature of cultural circulation and exchange during the period. With galleries closed, the private sphere of the home became a visual portal for artworks through front windows, as well as self-publishing via social media. In its rainbow gradient background, Deller recalled an earlier fundraising poster, Bless This Acid House, while Dominic Cummings Woz Ere, another recent collaboration between Fraser Muggeridge and Eleanor Vonne Brown, also used a similar background. The relatively low cost of Deller’s poster (it retailed at £25 in the UK) helped to accelerate and widen its distribution; like his video projects, which are mostly available to view for free online, Thank God For Immigrants adhered to the London-artist’s ethos of accessibility and participation.

In works such as The Battle of Orgreave (2001) and We’re Here, Because We’re Here (2016), Deller has democratised commemoration and evocation, recreating historical events in the public sphere in order to confront his audiences directly. With We’re Here, an installation that saw young men dressed in WWI uniforms walk around the UK, Deller explicitly stated that he wanted participants to roam around urban areas like shopping centres and cinema complexes, rather than forts and cathedrals; the aim was to create a visual incongruence for viewers to increase the work’s impact.

Does his poster design with Thank God For Immigrants continue this? Whereas We’re Here actively avoided prescribing a political message (beyond the implicit politics of commemorating Britain’s war dead), Deller’s latest poster is direct. It is also colloquial in its framing, expressing a holistic feeling that many people hold but often don’t have the opportunity to outwardly express. Through various shows of solidarity, the pandemic has allowed them to do so. The wording also allows Deller’s message to extend to immigration debates beyond the pandemic, at a time when party politics is providing little outright support for immigrants to the UK.

Thank God For Immigrants on display at Van Gogh House, Stockwell, London

“Its popularity reveals an artist in tune with progressive public opinion, who is unafraid to favour expressive and intelligible forms”

Although longrunning polling reveals that the number of Britons citing immigration as an issue of concern fell dramatically from June 2016 (47 percent) to November 2019 (13 percent), many of the anti-immigrant sentiments that have propelled British politics over the past four years—and which Deller captured in his Brexit film Putin’s Happy—remain intact, and now underpin factions within policy debates: particularly around migrant crossings and the so-called Australian-style points system. It could be argued that the poster’s message is vague, and politically unmoored in a time when support for vulnerable groups requires concrete strategies for change. There is also the question of whether the message is targeting the right people. But perhaps this is asking too much from an artistic project conceived in a spirit of positivity and collective gratitude.

Deller’s art can be more overtly critical too. Another of his lockdown posters features a black background with “Tax Avoidance Kills” pasted in white font in the centre. It’s an arresting contrast to the airy, jubilant colours of Thank God for Immigrants. The two works show that Deller is as aware of the injustices of the period as he is its successes. The popularity of Thank God for Immigrants reveals an artist in tune with progressive public opinion, who is unafraid to favour expressive and intelligible forms at a time when they’re most needed.