Under the Influence invites artists to discuss a work that has had a profound impact on their practice. In this edition painter Jesse Mockrin, whose contemporary works frequently transform the subjects of Old Masters, reflects on the effect that Hendrick ter Brugghen’s Saint Sebastian Tended by Saint Irene had on her.

At the start of last year, I began thinking about Dutch and Flemish game pieces, with banquet tables piled with dead animals and the like. I wanted to focus on this in my next solo exhibition, a big still life show to be held at Night Gallery in Los Angeles next May. The libraries were closed because of Covid, so I was just trying to buy as many used books as I could find on still life.

I came across a small black and white reproduction of Saint Sebastian Tended by Saint Irene in some massive volumes on Dutch painting. I didn’t know that there was this whole genre of paintings of Saint Irene taking care of Saint Sebastian. One of the only representations of his true death is a painting by Annibale Carracci, with all these people reaching in from different sides, like actors on scaffolding.

Previously I was only familiar with depictions of the martyrdom, where he’s tied to a tree and it’s all about the torso, the arrows, this look of ecstasy. And so the story of Saint Sebastian and the way he has been depicted over time became the narrative for my new paintings.

In the Ter Brugghen painting Sebastian is really grey, indicating his lack of health. But he survived being shot full of arrows and became a symbol of health, and so he’s considered a patron saint of plague. During the Black Death, the way people were praying to Saint Sebastian influenced the way he was depicted: he become younger and healthier looking.

“This erotic zone of the torso has been fetishised and impregnated with so much meaning over time”

My work is about how narratives change meaning and context over time

. That feedback loop between events in history and culture really engages me.

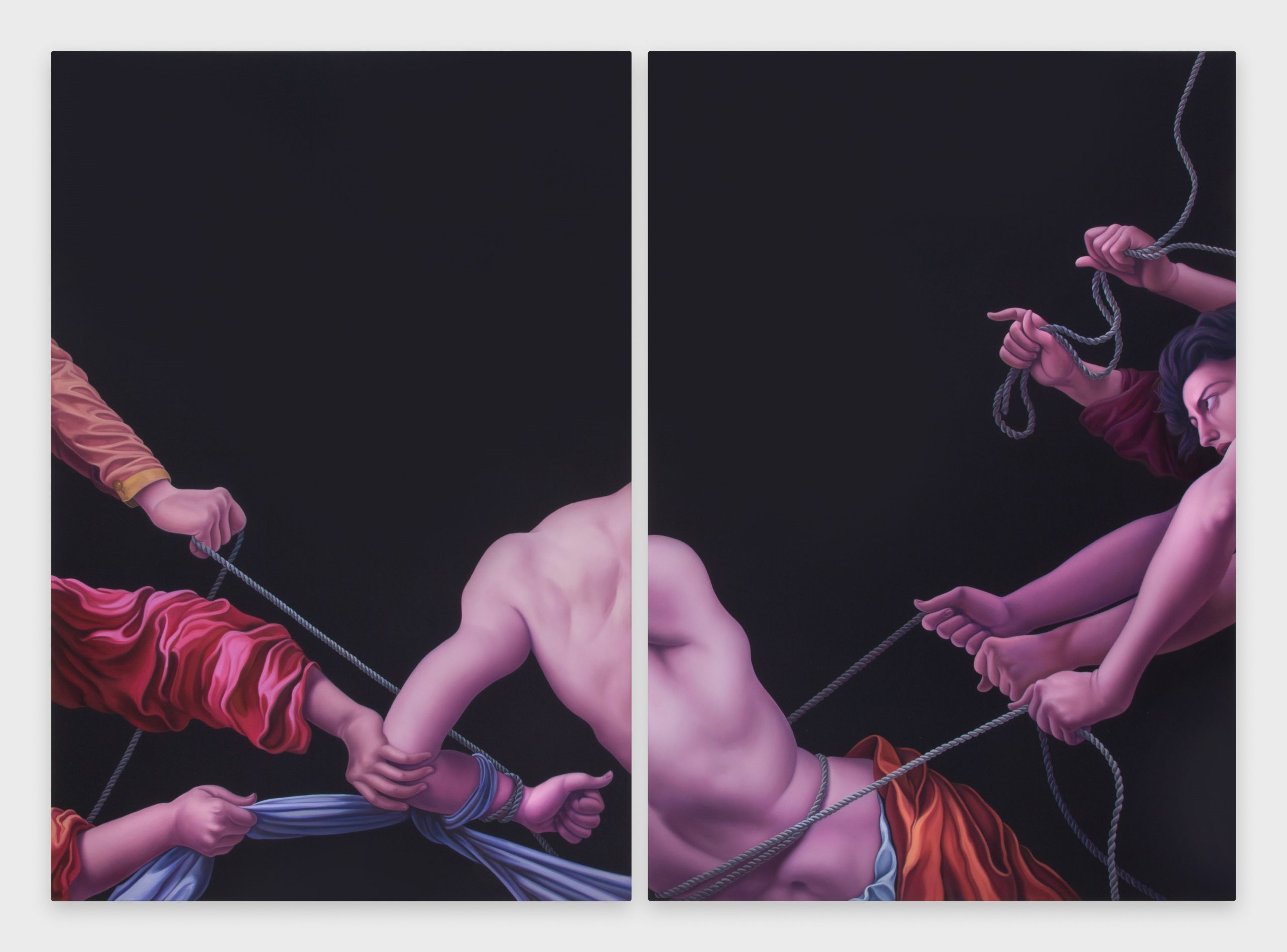

The composition and colour of this work are what was most interesting to me. The colours are a lot brighter in my works. I change the lighting in pretty much every painting. My version of this Ter Brugghen painting is backlit and has all this dappled light: there’s the light of the trees, the leaves falling on the body, and the fabric. It gives it a different atmosphere to the original.

“I still want them to feel androgynous, but maybe I’m letting more of the erotic content come through than I have before”

It’s a tough subject. There’s the duress that the body is under

, and then I’m cropping the bodies and putting them together again. I keep the body at the same scale in the paintings, so when they’re cropped, it feels like a series when you hang them in a show. There’s a narrative that’s forced upon them, because you’re seeing a glimpse of a scene here and there.

I almost always crop out any biological signs of gender, so nipples are not usually in the work. But here that didn’t feel quite right, because with Saint Sebastian this erotic zone of the torso has been fetishised and impregnated with so much meaning over time, that cutting that out felt like taking the meat out of the subject. I still want them to feel androgynous, but maybe I’m letting more of the erotic content come through in this body of work than I have before.

I wanted to have variety in the work, but also enough consistency that it’s about something

. It’s like poems in a book; they have to be related enough to each other, but different enough that it works. That’s more important to me than telling the story from the beginning to the end.

As told to Ravi Ghosh, Elephant’s editorial assistant