Colombian painter Jhonatan Pulido’s work uses bold, expressive colour palates to explore memory, place and escapism, both disrupting and affirming the images we conjure when prompted by visions of past. Drawing on the graffiti which plots the politically fraught history of his home country, Pulido embodies the various actors within Colombia’s national story while painting. “I am the civilian that uses some colours to decorate the front of the house, but also the guerrilla or paramilitary member who destroys it,” he says.

His works are large scale, vibrant panels, which often take inspiration from building facades, resulting in a sparse but noticeable use of line and shape. A graduate of the RCA in London and Universidad Nacional in Bogota, he describes his own artistic education as an ongoing process of fusion and stylistic negotiation. Spending lockdown in Colombia while his work is displayed at No 20 Arts in London, he contemplates the effects of time away from the studio, reintroducing playfulness to his works on paper, and reflecting on what awaits for his painting when he returns. “I prefer to focus on the fact that good things are to come in the future,” he says.

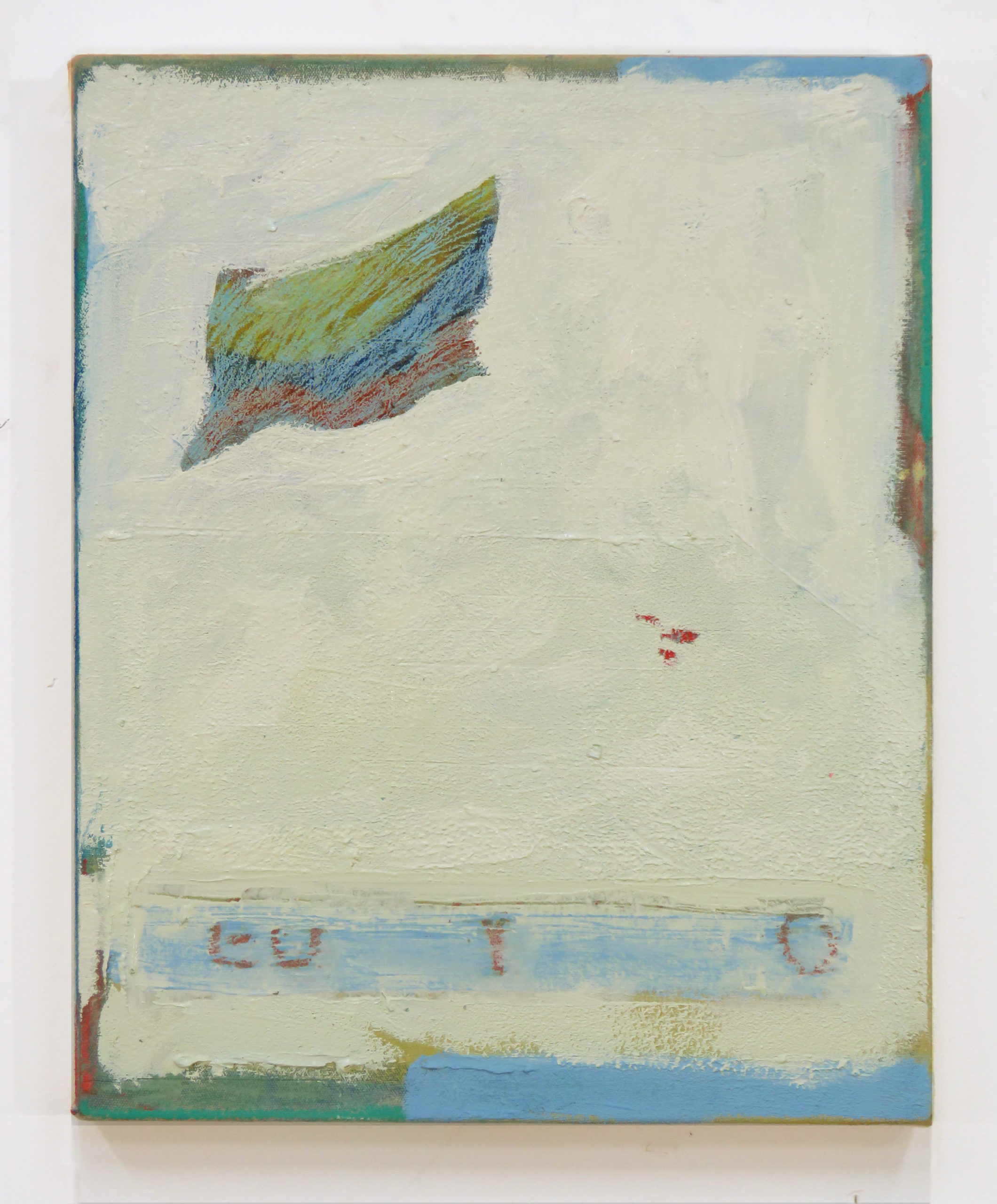

- Sunday Morning, 2020 (left); NN 075-09, 2019 (right)

How has your lockdown been in Colombia? How will this period influence your work?

Like anywhere in the world, these months have been full of great uncertainty, fear, sadness and expectation—especially for the poorest people in unstable work, who have received the least amount of aid from the national government here. Despite the difficulties, I’ve personally found a lot of time to think, write and rethink many things about my practice.

I’ve been making some works on paper, almost as if they were notes or scattered thoughts. I hope the lockdown will have a positive influence on my pictorial practice; I prefer to focus on the fact that good things are to come in the future, but I’ll only know that these are when I return to my studio in London. Hopefully, I won’t feel like a high-performance athlete who’s been injured for many months, and the transition back will be seamless.

“My relationship with colour comes from all that information and memories. The palette in my current work is reminiscent of a specific place”

Your use of colour is really assorted, yet lots of your paintings have this vibrant, pastel-bright quality in spite of the variation. How would you describe this relationship?

It was very important to get away, leave Colombia, and ask myself what my first encounters had been in terms of colour, composition and materiality of the painting. As a child and adolescent, I didn’t have access to museums or art galleries, so these questions have a complex origin. Through that intense exercise of going back to the past and scrutinising my memories, I realised that painting was always there around me, just not in the conventional artistic way. It was more functional, something that I began to understand just two years ago during my time at the RCA.

As in many other cultures, Colombians—especially people from the countryside or small towns—usually try to paint and decorate the front of their houses in a very particular way. Generally, the colours are mixed with lots of white, which gives them a pastel quality which in turn is much cheaper, so this combination of colour and surfaces becomes a reflection of the economy and local culture. The colour reflects the identity within. My relationship with colour comes from all that information and memories. The palette in my current work is reminiscent of a specific place. In my studio, images of paintings by artists I admire and who have influenced me have been replaced by photographic documents of popular Colombian architecture, which are very personal to me.

You use geometry in your work, but again in quite a liberal and unshackled way. How does this process come about?

As I mentioned, I use many decorative elements from Colombian popular painting, especially relating to housing facades. However, this comes unconsciously during the acts of removing, putting, showing, or covering certain texts or images during the making process. Since it’s not an intended or planned geometry, it loses its rigidity—that’s something that I really enjoy within my work.

Despite being influenced by certain tones or shapes, I never have an established plan or sketch before I begin. I prefer to obey the surface, allowing myself guided by the painting itself, and the time stretching out before me. The use of construction materials like rollers, scrapers, spatulas and wall brushes also enhances there irregularities in some way.

I’ve read that you’re influenced by graffiti, although the use of text in your work is quite sparse and selective. How do you think about text and messaging within your practice?

For me, the text is a way to hurt, to cut the canvas—and to create a contrast on the surface. My current work is full of graffiti and very specific texts that come from childhood memories, when rebel groups in Colombia imparted terror and exerted dominance over certain territories through intimidating texts on the walls, almost always written in red. In some way, these types of messages—being so direct, simple and intimidating—have a pictorial strength that I highlight. When I had my first encounter with one of these texts as I child, I still couldn’t read, so what I saw were the red signs or symbols on a sky blue surface. Ironically, what I could understand was the pictorial element, but not its political meaning.

Within my work, some of these texts can be read, others become a vestige of something that existed and others remain under the layers of paint, invisible for the viewer. I perform different roles while building the paintings. I become the civilian that uses some colours to decorate the front of the house, but also the guerrilla or paramilitary member who destroys it through a quick decision, and then finally the civilian again, who decides to rescue the house by covering the messages with heavy layers of paint. This is a process that is permeated by time, something that resembles a palimpsest, which I actively build and deconstruct.

- Another House, 2019 (left); Portrait of a Weapon, 2019 (right)

“For me, the text is a way to hurt, to cut the canvas—and to create a contrast on the surface”

How did your time at the RCA influence your practice? How does it compare to studying in Bogota?

The school of arts of Universidad Nacional in Bogota gave me a very broad overview of fine arts, made me see my own country and at the same time became a window to the world. Because of the school’s focus, I worked across different fields during my five year BFA, including video, drawing, sculpture and performance. The overall positive was that my interests in certain methods of working were reaffirmed.

On the other hand, the RCA gave me time to focus on a purely pictorial investigation that I had never done in the past. It was important to find elements that I ignored in my work, especially those related to large scale and surface. I used to paint small and very “cleanly,” so when I saw that many people worked in large formats and often on raw, unprepared fabrics, I realised that it was something that could enhance my ideas. I incorporated many of those elements without hesitation. It was two years of arduous experimentation, where the dialogue with colleagues and tutors helped to get me out of my comfort zone and towards new ways of working.